Loss of psychic self-activation (LPSA) is a syndrome first described by Laplane et al.1 in 1982, in a patient with lesions to the lenticular nuclei. The same group subsequently identified a further 3 cases,2 2 of which were caused by carbon monoxide poisoning.

The neologism athymhormia was coined in 1922 by Dide and Guiraud,3 and is derived from the Greek a- (not, without), thumos (mood, humour), and horme (impulse). The syndrome is characterised by the loss of mood and impulse in the absence of physical alterations.

The most relevant clinical sign in these patients is psychic akinesia, causing a reduction in mental and behavioural activity.

Altitude sickness is the body’s lack of adaptation to low oxygen levels at high altitudes. The severity of the disorder is directly correlated with the speed of ascent and the altitude reached. Altitude sickness causes lesions to the globus pallidus, visible on MRI studies, which can probably cause athymhormia or LPSA.4,5

We present a case demonstrating that altitude sickness can cause LPSA.

Case reportThe patient was a 57-year-old man who, during a hiking trip in Peru, stayed in an area located 5000 m above sea level.

There, he presented severe headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and drowsiness; he and his wife, who presented similar symptoms, were treated with oxygen therapy. The wife recovered rapidly, whereas the patient continued to present drowsiness, bradylalia, and bradyphrenia, which persisted until his return to Spain. His wife reported that she had stopped and rested more frequently than her husband during the tour.

Although the patient was performing physical exercise at a very high altitude, at no time did he exceed the level of exertion required to complete the route.

In the consultation, the patient presented an appropriate attitude when entering the consultation room, but showed no interest, fear, or concern, and allowed his family to describe the facts on his behalf.

He remembered the symptoms he had presented, but showed no emotion, not even sadness, about his situation. Speech was correct, but lacked the normal changes in tone. He described his mind as feeling “empty” and lacked interest in reading or television, which he had greatly enjoyed previously, but voiced no concern. His companion emphasised that he had been indifferent to family matters and social relationships.

In the general examination, the patient was cooperative and presented no fever and no alterations in the cardiopulmonary auscultation; the abdomen was soft and depressible, and the skin and mucosa showed good colouration. Peripheral pulses were palpable and symmetrical. The neurological examination detected no cranial nerve alterations, preserved strength of all 4 limbs, normal coordination and sensitivity, and symmetrical reflexes. Plantar reflexes were flexor, and gait was somewhat slow but presented no clear alterations. Romberg sign was negative and the patient was able to walk in tandem.

The patient reported no known history of haematological alterations or cardiac or pulmonary disorders. He had been using no medications prior to symptom onset.

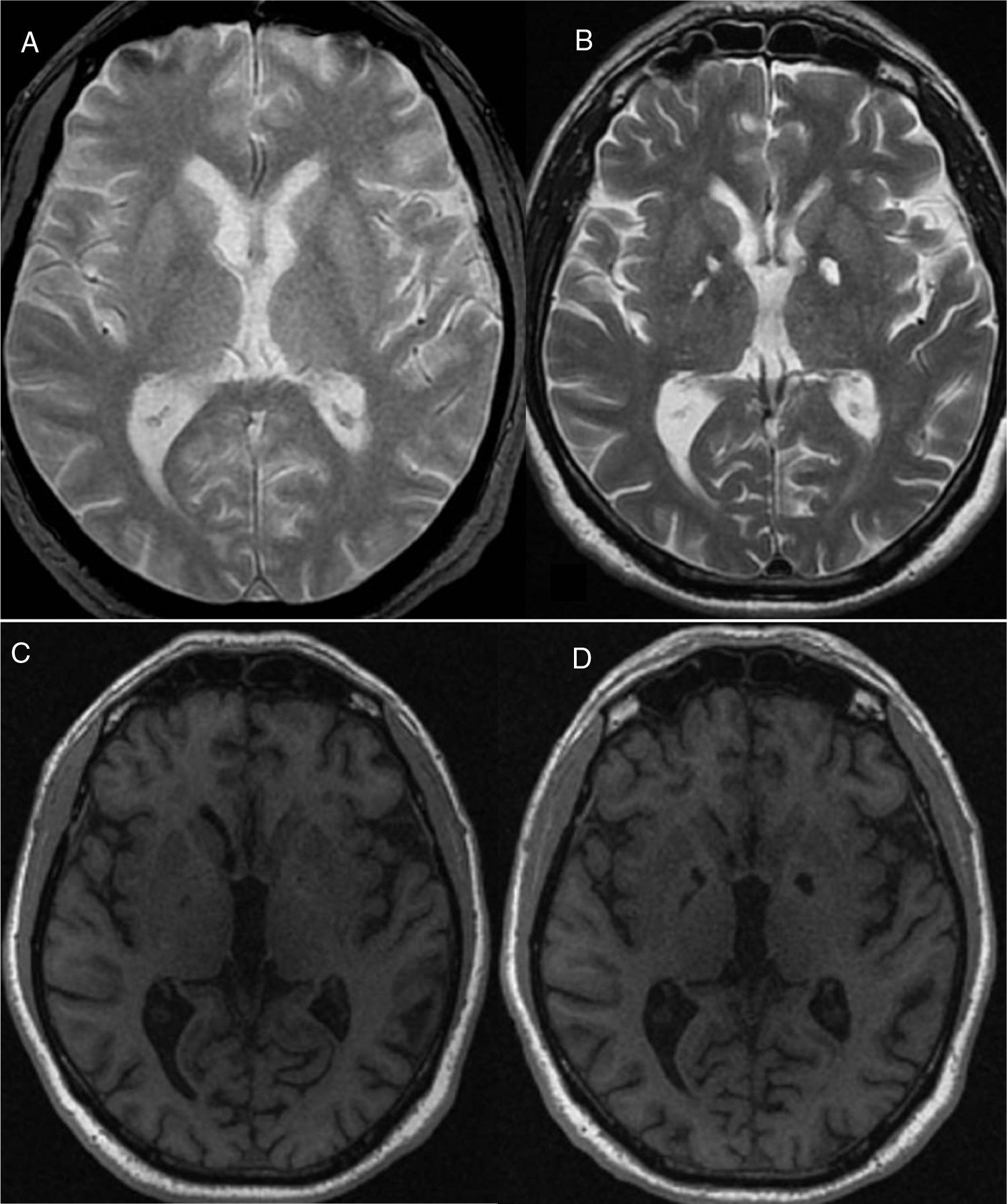

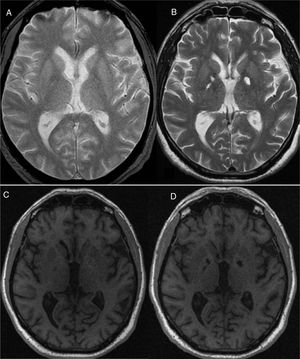

Findings from an electrocardiogram performed 15 days later were completely normal. An MRI study (Fig. 1A and C) showed subcortical lesions of possible vascular aetiology, as well as discreet cortical-subcortical atrophy.

In terms of cognition, he displayed moderate bradyphrenia, mild working memory alterations, and a disorder of memory coding and organisation, predominantly affecting prefrontal subcortical functions. He also presented alterations in information processing speed and certain executive functions, compatible with frontal-subcortical syndrome.

In a second MRI study performed 4 months later (Fig. 1B and D), the globus pallidus was markedly hyperintense on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences and hypointense on T1-weighted sequences, bilaterally.

DiscussionOur patient presented symptoms of hypoxic encephalopathy associated with altitude sickness, after spending several days above 5000 m of altitude. The hypoxia caused by altitude sickness can cause lesions to the globus pallidus, resulting in LPSA.

As the hypoxic lesions were very well delimited in the area of the globus pallidus, the lesion was probably very specific, without involvement of motor or sensory pathways. Our patient’s symptoms may be explained by a dorsolateral frontal lobe lesion associated with globus pallidus involvement.6

Since the first case described by Laplane et al.1 in 1982, other cases have been described of local lesions involving the basal ganglia, striatum, and globus pallidus, which may cause symptoms of loss of motivation similar to athymhormia or LPSA.7–9

Ali-Chérif et al.10 described 3 new cases of pallidal lesions secondary to carbon monoxide poisoning, underscoring the behavioural and mental alterations observed; this confirms the role of the globus pallidus in these functions.

Patients with athymhormia may have thoughts that cannot be acted upon without a presumably subcortical activation system that excites an intact but inactive cortical system.11

Hypoxia involving the basal ganglia is a known result of carbon monoxide poisoning, and is probably explained by increased sensitivity of these structures to hypoxia. We suspect that altitude sickness and hypoxia may be a trigger factor in patients who do not necessarily present other predisposing conditions, or with unknown predisposing conditions.

In summary, athymhormia in our patient was evidently associated with hypoxia secondary to altitude sickness, and demonstrates a clear pathophysiological relationship with bilateral globus pallidus lesions.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Neuroinvest and the DINAC Foundation for the assistance granted for the preparation of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Izquierdo G and Borges M. Acinesia psíquica (atimormia), producida por hipoxia en relación al mal de altura. Neurología. 2021;36:180–182.