A picture version of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) would assist in the assessment of memory function in patients with low levels of schooling. A shortened version would improve the test's applicability.

ObjectivesTo analyse the diagnostic usefulness of a shortened picture version of the FCSRT for distinguishing patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) from controls, without excluding participants with a low level of schooling.

MethodsPhase I study of a diagnostic evaluation (convenience sampling; pre-test prevalence 50%). A blinded researcher independently administered the FCSRT to 30 patients with aMCI and 30 controls matched for age, sex, level of schooling and literacy, using images and omitting the usual 30-minutes delayed recall item. Three variables were recorded: free recall, total recall, and cue efficiency. Diagnostic accuracy was calculated using receiver operating characteristic curves and the area under the curve. The Youden index was used to identify optimal cut-off points.

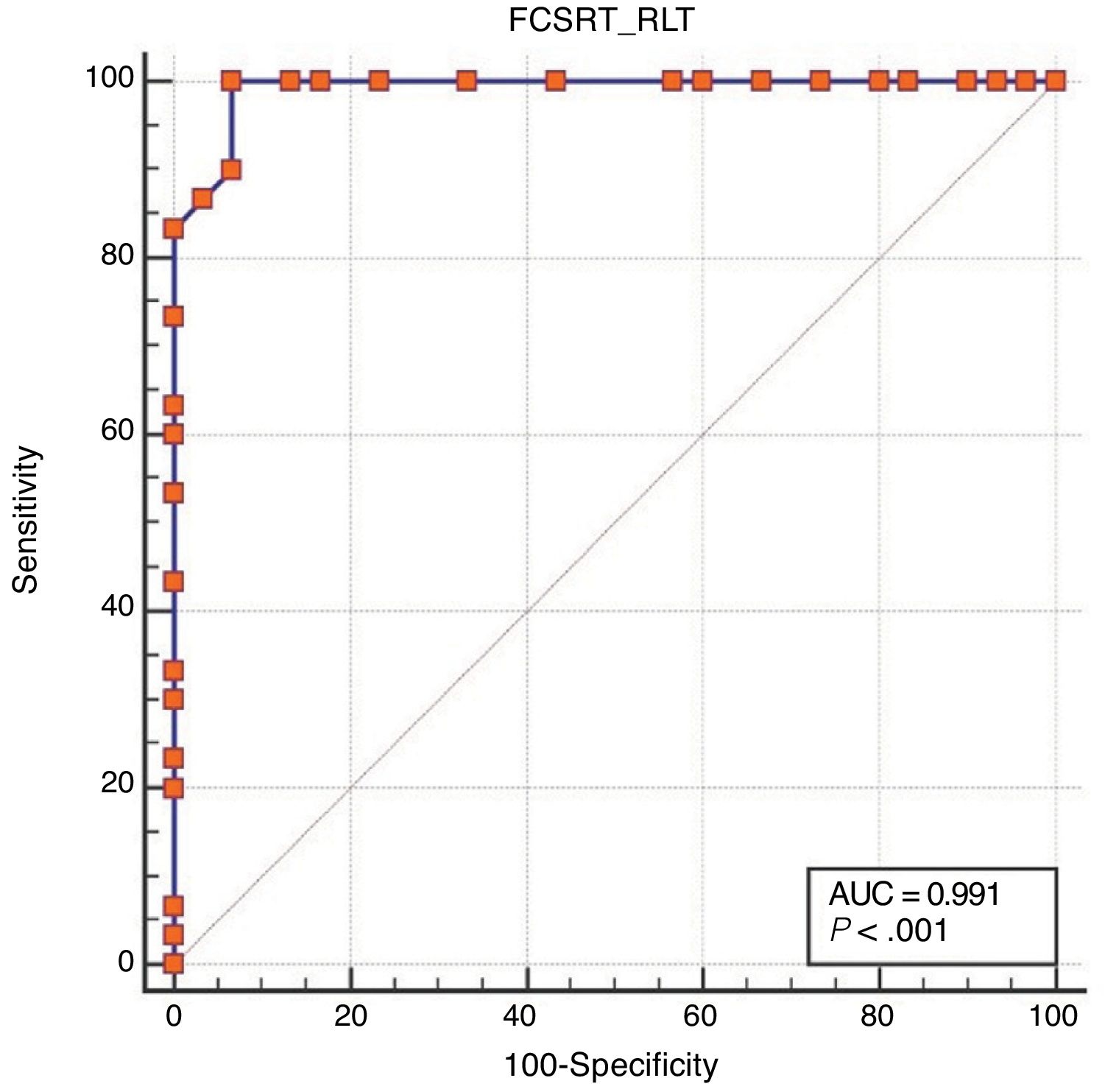

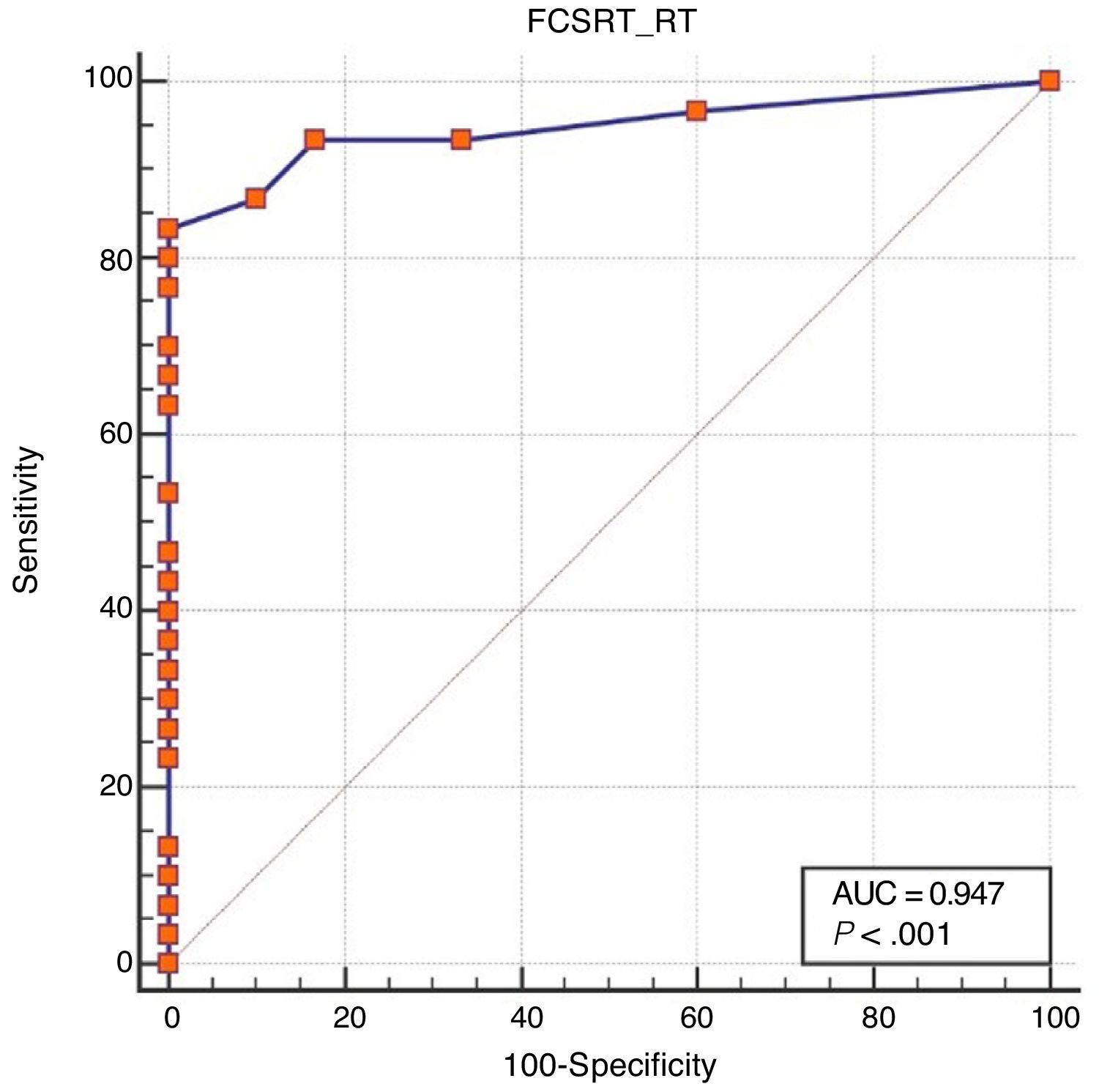

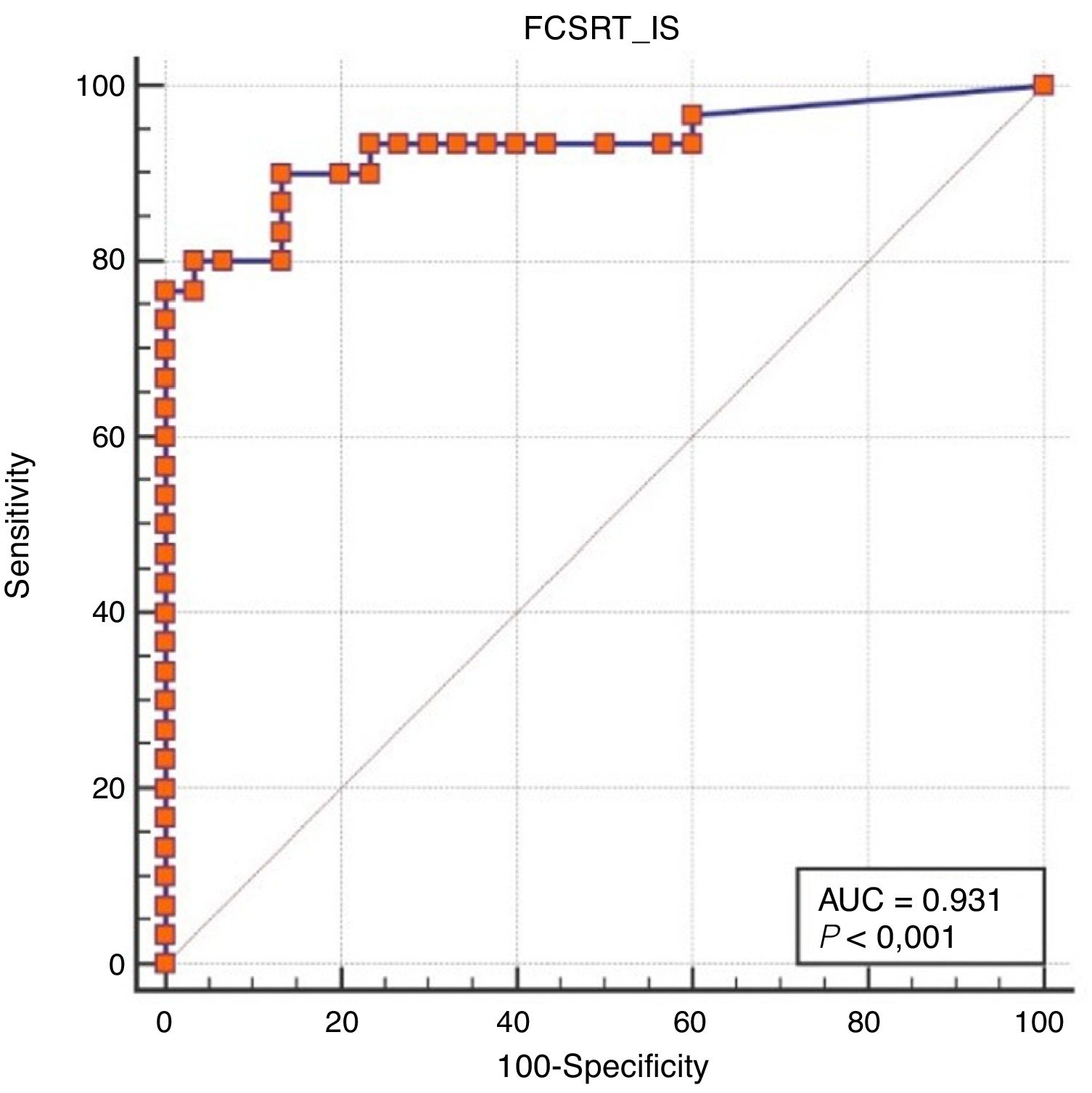

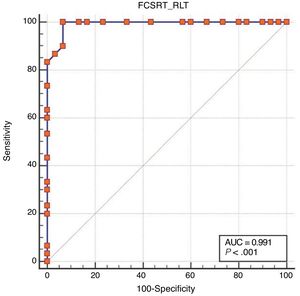

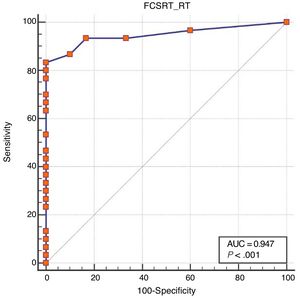

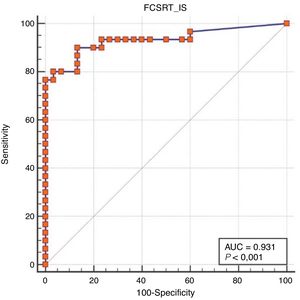

ResultsOf all participants, 41.7% had not completed primary education. There were no differences between groups as regards sociodemographic variables. Area under the curve was excellent for free recall (0.99), total recall (0.95), and cue efficiency (0.93). The optimal cut-off points were 21/22, 43/44, and < 0.77, respectively.

ConclusionsThis preliminary analysis shows that a shortened picture version of the FCSRT may be useful and applicable for the diagnosis of aMCI without excluding individuals with a low level of schooling.

Una versión pictórica del Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) facilitaría la evaluación de la memoria en pacientes con bajo nivel educativo. Una forma abreviada mejoraría la aplicación.

ObjetivoAnalizar la utilidad diagnóstica de una versión pictórica y abreviada del FCSRT para distinguir pacientes con deterioro cognitivo leve amnésico (DCLa) de controles, sin excluir a individuos con un nivel educativo bajo.

MétodoEstudio en fase i de evaluación de prueba diagnóstica (muestreo de conveniencia, prevalencia pretest del 50%). El FCSRT fue administrado, de forma independiente y ciega al diagnóstico, a 30 pacientes con DCLa (recomendaciones NIA-AA 2011) y a 30 controles emparejados por edad, género, nivel educativo y grado de alfabetización, utilizando imágenes y obviando el ensayo diferido. Tres variables resultado fueron registradas: recuerdo libre total, recuerdo total e índice de sensibilidad a la pista. La utilidad diagnóstica fue calculada mediante el área bajo la curva ROC. El índice Youden fue usado para seleccionar los mejores puntos de corte.

ResultadosEl 41,7% de los participantes no habían completado estudios primarios. No hubo diferencias entre los 2grupos respecto a las variables sociodemográficas. Las áreas bajo la curva fueron óptimas para recuerdo libre total (0,99), recuerdo total (0,95) e índice de sensibilidad a la pista (0,93). Los mejores puntos de corte fueron 21/22, 43/44 y <0,77, respectivamente.

ConclusiónEsta evaluación preliminar demuestra que una versión pictórica y abreviada de FCSRT puede ser útil y aplicable en el diagnóstico de DCLa sin excluir a individuos con un nivel educativo bajo.

Diagnosing Alzheimer disease (AD) in the prodromal phase is a common objective in the management of dementia. Diagnosis is currently based on memory tasks and pathophysiological markers.1 The International Working Group (IWG) 2 diagnostic criteria for AD include a specific profile of episodic memory impairment characterised by poor free recall that is not normalised by cueing.1 This profile is different from that observed in patients with other conditions, such as frontotemporal dementia, Huntington disease, or major depression, in which recall is normalised by cueing.2–4

To assess this paradigm, the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT)5 was specifically recommended in the 2014 IWG-2 diagnostic criteria.1 The test controls for encoding by cued recall, and favours the process of retrieval using the same semantic cues.6 Poor total recall despite cueing presents excellent specificity for AD.7 Furthermore, low scores in the test have been correlated with hippocampal atrophy,8 loss of grey matter in the medial temporal lobes,9 and positive results for AD biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid,10 even in the prodromal phase.11

Several versions of the FCSRT have been developed. The differences consist of the number of items to be memorised, the use of words or images as cues, and how the test is administered. The most frequently used versions include 16 items, but, for example, 12-item versions also exist.12 We know that scores in the word and picture versions are not interchangeable, as dual encoding represents an advantage in the former.13 A word version has been validated in Spain,14 but no picture version has ever been validated; such a study would be beneficial, considering that many Spanish citizens in the sixth, seventh, or eighth decade of life have low levels of education, and a picture version of the instrument may be more appropriate in their case. Finally, the test may be administered in different ways. In one version,15 the study phase is followed by 3 memory rehearsals and the usual 30-minutes deferred recall test is omitted, enabling faster application without losing the information most frequently analysed in the test, the results of the initial 3 memory tests.

In this study, we used a picture version of the FCSRT, applying the abbreviated version previously described.15 We propose that this tool would be useful for distinguishing between patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) and controls, with no need to exclude individuals with low levels of education.

MethodsDesignWe performed a phase I study 6 (cross-sectional, case-control, convenience sampling, pretest prevalence of 50%) to assess the diagnostic accuracy of an abbreviated picture version of the FCSRT for distinguishing between patients with aMCI and controls.

Study populationThe sample included 60 participants who were resident in Spain, divided into 2 groups, aMCI and controls, matched for age, sex, level of education, and level of literacy. All participants were older than 60 years and were native Spanish speakers. Demographic variables included: age, sex, level of education (not completed primary school, completed primary school, secondary studies), and level of literacy (illiterate, able to read and write but not fluently, able to read and write fluently).

All participants were selected by convenience sampling of consecutive cases diagnosed with aMCI at the Memory Unit of Hospital Virgen del Rocío (Seville). They underwent general and neurological examination, neuropsychological evaluation, and laboratory analysis and neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychological examination included a Spanish-language version of the informant-based AD8 questionnaire,17,18 the Fototest,19,20 the Delayed Matching-to-Sample Task 48 (DMS-48),21,22 the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale,23 and the Interview for Deterioration in Daily Living Activities in Dementia (IDDD).24 Diagnosis of aMCI was established according to the 2011 recommendations of the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association25 and using the following parameters: (a) memory complaints corroborated by a reliable informant, (b) objective memory complaint shown by a score equal to or lower than the 10th percentile in set 2 of the DMS-48 test, provided that this score was lower than that obtained in set 1, and (c) no significant disability for the activities of daily living (a score of up to 39 in the IDDD was acceptable).

Controls were recruited from among the caregivers and family members of patients visiting the hospital. They met 3 criteria: (a) no memory complaints, (b) no objective memory impairment (score on set 2 of the DMS-48 test equal to or higher than the 25th percentile), and (c) independence for activities of daily living (score between 33 and 36 in the IDDD).

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) absence of a reliable informant, (2) current neurological disease that may cause cognitive impairment, (3) poor vision or hearing despite correction, (4) diagnosis of active major depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder according to the DSM-V, and (5) history of alcohol or substance abuse.

Tool: abbreviated picture version of FCSRTTo avoid circularity, the test was administered in a single session, regardless of the procedures performed to assign participants to the aMCI or control group. The examiner was blinded to these procedures and to the group to which each participant was assigned. The abbreviated version of the FCSRT was applied according to the authors’ instructions.15

The test starts by asking the subject to consecutively identify images distributed in 4 quadrants of a sheet of paper; the subject is given a single cue, the semantic category to which the object belongs. Once all 4 objects have been identified, the sheet is removed and immediate recall is assessed by providing the cue once more. The objects that subjects are unable to recall are presented again, together with the cue. Once immediate recall of a group of 4 objects is achieved, the next sheet is presented, and so on, until 16 items from 4 sheets are remembered. The memory phase includes 3 consecutive recall trials, preceded by a distraction task consisting of counting backwards from 20. Each recall trial includes a free phase in which the subject has up to 2minutes to name all the objects that he or she recalls from the study phase, no matter the order. Following the order of presentation, a semantic cue is offered for those items not remembered in the free phase. During the cued recall of the first and second memory tests, if the correct object is not evoked, the examiner names it again, together with the corresponding cue. We recorded the following variables: total free recall (TFR) (sum of free recall items from all 3 trials); total recall (TR) (sum of the free recall and total cued recall in the 3 memory trials); sensitivity to cueing index (SCI) (calculated as follows: [TFR–TR]/[TFR–48]).15

EthicsThe study was approved by the ethics committee of Hospital Virgen del Rocío (Seville, Spain) and conducted in accordance with the Spanish Law 14/2007, of 3 July, on biomedical research. All participants signed informed consent forms agreeing to the study procedures.

Statistical analysisWe used the t test and the chi-square test to make comparisons between groups, depending on the variables. Descriptive results are expressed as frequency (percentage) or mean (standard deviation) for categorical or continuous variables, respectively. The diagnostic accuracy of the FCSRT was calculated using ROC curve analysis, and is expressed as the area under the curve (AUC). The Youden index26 was used to determine the optimal cut-off point for an adequate balance between sensitivity and specificity. We used the Pearson correlation coefficient to test the convergent validity of FCSRT scores (TFR, TR, SCI) with the total scores obtained in the tests used for diagnosis (DMS-48 and Fototest). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24. Statistical significance was set at P<.05. Estimates are provided with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

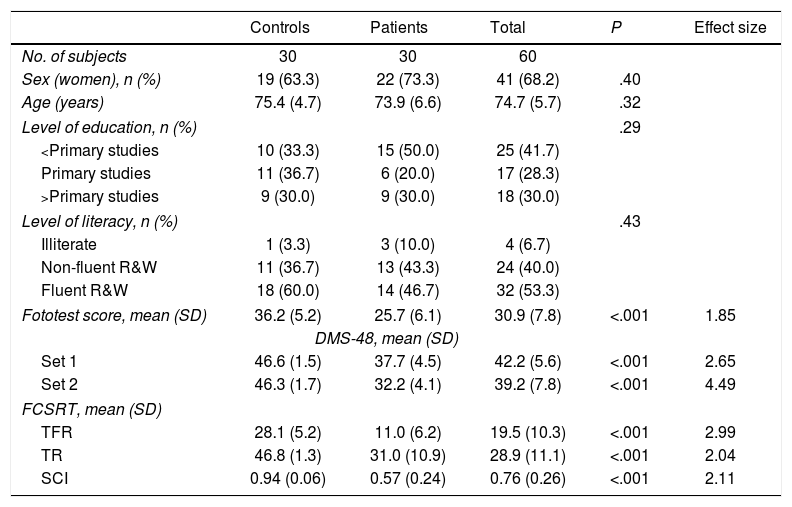

ResultsTable 1 presents data on sociodemographic variables and neuropsychological test results. No significant differences were identified between groups with regard to age, sex, level of education, or level of literacy. Subjects who had not completed primary studies represented 41.7% of the sample.

Sociodemographic characteristics and scores in the neuropsychological tests by diagnostic group.

| Controls | Patients | Total | P | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects | 30 | 30 | 60 | ||

| Sex (women), n (%) | 19 (63.3) | 22 (73.3) | 41 (68.2) | .40 | |

| Age (years) | 75.4 (4.7) | 73.9 (6.6) | 74.7 (5.7) | .32 | |

| Level of education, n (%) | .29 | ||||

| <Primary studies | 10 (33.3) | 15 (50.0) | 25 (41.7) | ||

| Primary studies | 11 (36.7) | 6 (20.0) | 17 (28.3) | ||

| >Primary studies | 9 (30.0) | 9 (30.0) | 18 (30.0) | ||

| Level of literacy, n (%) | .43 | ||||

| Illiterate | 1 (3.3) | 3 (10.0) | 4 (6.7) | ||

| Non-fluent R&W | 11 (36.7) | 13 (43.3) | 24 (40.0) | ||

| Fluent R&W | 18 (60.0) | 14 (46.7) | 32 (53.3) | ||

| Fototest score, mean (SD) | 36.2 (5.2) | 25.7 (6.1) | 30.9 (7.8) | <.001 | 1.85 |

| DMS-48, mean (SD) | |||||

| Set 1 | 46.6 (1.5) | 37.7 (4.5) | 42.2 (5.6) | <.001 | 2.65 |

| Set 2 | 46.3 (1.7) | 32.2 (4.1) | 39.2 (7.8) | <.001 | 4.49 |

| FCSRT, mean (SD) | |||||

| TFR | 28.1 (5.2) | 11.0 (6.2) | 19.5 (10.3) | <.001 | 2.99 |

| TR | 46.8 (1.3) | 31.0 (10.9) | 28.9 (11.1) | <.001 | 2.04 |

| SCI | 0.94 (0.06) | 0.57 (0.24) | 0.76 (0.26) | <.001 | 2.11 |

DMS-48: Delayed Matching-to-Sample Task 48; FCSRT: Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test; R&W: reading and writing in Spanish; SD: standard deviation; SCI: sensitivity to cueing index; TFR: total free recall; TR: total recall.

All participants consented to perform the FCSRT and completed the test.

The aMCI group scored significantly lower than the control group for TFR (11.2 [6.2] vs. 28.1 [5.2]; P<.001; Cohen d=2.99), TR (31.0 [10.9] vs. 46.8 [1.3]; P<.001; Cohen d=2.04), and SCI (0.57 [0.24] vs. 0.94 [0.06]; P<.001; Cohen d=2.11) (Table 1).

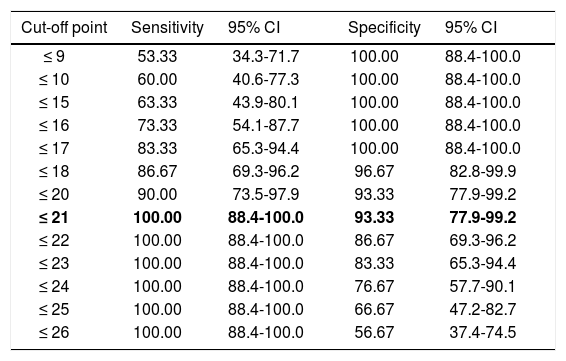

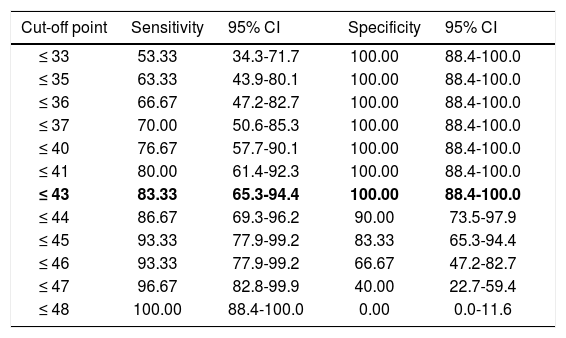

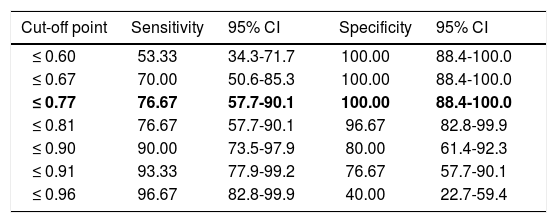

Regarding diagnostic accuracy, ROC curve analysis showed an AUC of 0.99 (95% CI, 0.92-1.00) for TFR (Fig. 1). The optimal cut-off point for distinguishing between patients with aMCI and controls was 21/22 (Youden index, J=0.93), with sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.88-1.00), and specificity of 0.95 (95% CI, 0.78-0.99) (Table 2). For TR, the AUC was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.86-0.99) (Fig. 2) and the optimal cut-off point was 43/44 (Youden index, J=0.83), with sensitivity of 0.83 (95% CI, 0.65-0.94) and specificity of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.88-1.00) (Table 3). For SCI, the AUC was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.83-0.98) (Fig. 3) and the optimal cut-off point was < 0.77 (Youden index, J=0.76), with sensitivity of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.58-0.90) and specificity of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.88-1.00) (Table 4).

Sensitivity and specificity for different TFR cut-off points.

| Cut-off point | Sensitivity | 95% CI | Specificity | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 9 | 53.33 | 34.3-71.7 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 10 | 60.00 | 40.6-77.3 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 15 | 63.33 | 43.9-80.1 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 16 | 73.33 | 54.1-87.7 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 17 | 83.33 | 65.3-94.4 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 18 | 86.67 | 69.3-96.2 | 96.67 | 82.8-99.9 |

| ≤ 20 | 90.00 | 73.5-97.9 | 93.33 | 77.9-99.2 |

| ≤ 21 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 | 93.33 | 77.9-99.2 |

| ≤ 22 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 | 86.67 | 69.3-96.2 |

| ≤ 23 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 | 83.33 | 65.3-94.4 |

| ≤ 24 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 | 76.67 | 57.7-90.1 |

| ≤ 25 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 | 66.67 | 47.2-82.7 |

| ≤ 26 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 | 56.67 | 37.4-74.5 |

The optimal cut-off point is shown in bold. CI: confidence interval; TFR: total free recall.

Sensitivity and specificity for different TR cut-off points.

| Cut-off point | Sensitivity | 95% CI | Specificity | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 33 | 53.33 | 34.3-71.7 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 35 | 63.33 | 43.9-80.1 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 36 | 66.67 | 47.2-82.7 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 37 | 70.00 | 50.6-85.3 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 40 | 76.67 | 57.7-90.1 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 41 | 80.00 | 61.4-92.3 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 43 | 83.33 | 65.3-94.4 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 44 | 86.67 | 69.3-96.2 | 90.00 | 73.5-97.9 |

| ≤ 45 | 93.33 | 77.9-99.2 | 83.33 | 65.3-94.4 |

| ≤ 46 | 93.33 | 77.9-99.2 | 66.67 | 47.2-82.7 |

| ≤ 47 | 96.67 | 82.8-99.9 | 40.00 | 22.7-59.4 |

| ≤ 48 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 | 0.00 | 0.0-11.6 |

The optimal cut-off point is shown in bold. CI: confidence interval; TR: total recall.

Sensitivity and specificity for different SCI cut-off points.

| Cut-off point | Sensitivity | 95% CI | Specificity | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 0.60 | 53.33 | 34.3-71.7 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 0.67 | 70.00 | 50.6-85.3 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 0.77 | 76.67 | 57.7-90.1 | 100.00 | 88.4-100.0 |

| ≤ 0.81 | 76.67 | 57.7-90.1 | 96.67 | 82.8-99.9 |

| ≤ 0.90 | 90.00 | 73.5-97.9 | 80.00 | 61.4-92.3 |

| ≤ 0.91 | 93.33 | 77.9-99.2 | 76.67 | 57.7-90.1 |

| ≤ 0.96 | 96.67 | 82.8-99.9 | 40.00 | 22.7-59.4 |

The optimal cut-off point is shown in bold. CI: confidence interval; SCI: sensitivity to cueing index.

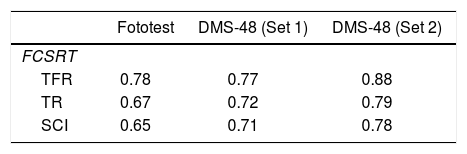

TFR score was significantly correlated with scores in set 1 (r=0.77; P<.001) and set 2 (r=0.88; P<.001) of the DMS-48 and with total Fototest score (r=0.78; P<.001). TR score was significantly correlated with scores in set 1 (r=0.72; P<.001) and set 2 (r=0.79; P<.001) of the DMS-48 and with total Fototest score (r=0.67; P<.001). Total SCI score was significantly correlated with scores in set 1 (r=0.71; P<.001) and set 2 (r=0.78; P<.001) of the DMS-48 and with total Fototest score (r=0.65; P<.001) (Table 5).

Correlations (r) between FCSRT scores (TFR, TR, SCI) and total scores in the tests used for diagnosis (Fototest, DMS-48).

| Fototest | DMS-48 (Set 1) | DMS-48 (Set 2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCSRT | |||

| TFR | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.88 |

| TR | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.79 |

| SCI | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.78 |

DMS-48: Delayed Matching-to-Sample Task 48; FCSRT: Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test; SCI: sensitivity to cueing index; TFR: total free recall; TR: total recall.

The FCSRT is already seen as a classic test and is particularly recommended in the IWG-21 diagnostic criteria due to its ability to detect the specific profile of memory loss characterising AD. The test is widely used to screen for patients with AD for inclusion in clinical trials of potential disease-modifying therapies. These candidates are usually required to have a minimum of 8 years of education and are examined with a word version of the FCSRT. Patients with low levels of education are excluded from trials, mainly due to the lack of memory tests that enable us to reliably assess them. A similar problem arises when examining candidates who are immigrants from other cultural settings. The use of such picture-based memory tests as the DMS-48,21 TMA-93,27 or the picture version of the FCSRT may overcome this difficulty. Normative and validation studies are needed.

Ours is the first validation study of a picture version of the FCSRT in Spain. This is a phase I preliminary validation study16 of an abbreviated version of the test in a sample including participants with low levels of education. It presents optimal diagnostic accuracy (above 0.9) for distinguishing patients with AD from controls, which was shown for all 3 variables analysed in the test (TFR, TR, and SCI). The optimal cut-off points were 21/22 for TFR, 43/44 for TR, and < 0.77 for SCI.

All participants completed the test without impediment, including the 41.7% who had not completed primary education. Following the instructions proposed by Grober et al.15 in 2000, the test was easy to administer and to score. These data support the good applicability of the test.

Our study presents some limitations. Its design may have introduced a selection bias: convenience sampling is not representative of a normal population or a population with dementia. However, the main requirement in the preliminary evaluation of a diagnostic test is that the 2 groups (patients and controls) present the same values for confounding variables and different results in diagnosis.28 Our study met this requirement.

These results encourage us to continue with the validation process of this instrument, progressing to the next step: a phase II validation study including a more representative sample of the Spanish population, and with different objectives, such as identifying the test's predictive value in the diagnosis of dementia in settings with low prevalence of the disease (for example, primary care).

ConclusionsAn abbreviated picture version of the FCSRT showed optimal diagnostic accuracy for distinguishing between patients with aMCI and controls in a sample including patients with low levels of education. This study constitutes a first, preliminary, validation of this version of the FCSRT in Spain.

FundingThe authors have received no funding of any kind for this research study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr Carnero-Pardo designed the Fototest.

Please cite this article as: Rodrigo-Herrero S, Mendez-Barrio C, Bernal Sánchez-Arjona M, de Miguel-Tristancho M, Graciani-Cantisán E, Carnero-Pardo C, et al. Evaluación preliminar de una versión pictórica y abreviada del Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test. Neurología. 2022;37:192–198.