Digestive disorders are one of the most common comorbidities among children with cerebral palsy (CP). The aim of this study is to examine the nutritional status of patients with CP, the prevalence of dysphagia by degree of motor impairment, and the impact of digestive disorders on quality of life.

Material and methodsWe conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional, open-label study of out-patients with CP from a tertiary hospital in the Region of Madrid using a structured interview, classifying dysphagia using the Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS). We gathered demographical and anthropometric data, and analysed the correlation between severity of dysphagia and functional status as measured with the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS).

ResultsOur sample included 44 patients (65.9% boys), with a mean (standard deviation) age of 9.34 (5) years and a mean BMI of 18.5 (4.9). Forty-three percent presented safety and efficiency limitations (EDACS level > II). Safety and efficiency limitations were associated with more extensive motor involvement (60% had tetraparesis), more varied clinical manifestations (87% had mixed forms) and poorer functional capacity (100% on GMFCS V). The impact on nutritional status increased with higher EDACS and GMFCS scores.

ConclusionsThis is the first study into the usefulness of the EDACS scale in a representative sample of Spanish children and adolescents with CP. Our findings underscore the importance of screening for dysphagia in these patients, regardless of the level of motor impairment, and the need for early treatment to prevent the potential consequences: malnutrition (impaired growth, micronutrient deficiencies, osteopaenia, etc.), microaspiration, or recurrent infections that may worsen patients’ neurological status.

La enfermedad digestiva es una de las comorbilidades más frecuentes en niños con parálisis cerebral infantil (PCI). Nuestro objetivo es analizar el estado nutricional de los pacientes PCI, la prevalencia de disfagia según afectación motriz (GMFCS) y su repercusión en la calidad de vida.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo transversal y abierto en pacientes con PCI seguidos en un Hospital Terciario de la Comunidad de Madrid mediante entrevista estructurada y clasificación de disfagia según la escala Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS). Recogimos datos demográficos y antropométricos y relacionamos el nivel de disfagia con el nivel funcional según el Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS).

ResultadosLa muestra incluyó 44 pacientes (65,9% varones), con una edad media de 9,34 ± 5 años y un IMC de 18,5 ± 4,9. El 43% tenía limitaciones en seguridad y/o eficiencia (EDACS > II). El porcentaje de pacientes afectados fue mayor cuanto más extensa desde el punto de vista topográfico (tetraparesia 60%), más variada semiología clínica (87% en formas mixtas) y peor nivel funcional (100% en GMFCS V). La repercusión nutricional fue mayor cuanto mayor nivel EDACS y GMFCS.

ConclusionesPresentamos el primer estudio sobre la utilidad de la escala EDACS en una muestra representativa de niños y adolescentes españoles con PCI. Los resultados deben hacernos reflexionar sobre la importancia del screening de disfagia en estos pacientes, independientemente del grado de afectación motriz y la necesidad de una intervención precoz para evitar sus principales consecuencias: desnutrición (hipocrecimiento, déficit de micronutrientes, osteopenia, etc.), microaspiraciones o infecciones de repetición que empeoran el estado neurológico.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most frequent cause of disability in children in developed countries. Its prevalence ranges from 1.5 to 3 cases per 1000 live births; however, the development of follow-up protocols, palliative care units, and advances in medical care have improved the life expectancy of these patients, increasing the global prevalence of the disease.1,2

CP encompasses a heterogeneous group of syndromes involving persistent motor dysfunction secondary to a lesion to the developing brain, affecting muscle tone, movement, and posture.3 Although the disease, by definition, is not progressive, its clinical expression varies according to the patient’s age and the appearance of a broad range of comorbidities that can affect quality of life to an even greater extent than the neurological disorder.4

Comorbidities affecting the digestive tract are the most frequent, after the associated neurological disorders. Nearly all patients with CP present gastrointestinal symptoms and/or impaired nutritional status at some point in their lives.5,6

Up to 30%-40% of patients present feeding difficulties secondary to dysphagia, vomiting or regurgitation, and delayed gastric emptying. These problems, compounded by the reliance on another person for food intake, difficulty expressing hunger or satiety, potential alterations in trunk posture and balance (hindering food intake); and increased caloric loss or requirements, directly result in a risk of insufficient food intake and, therefore, of malnutrition.7–10

In the light of these considerations, it is important to be aware of possible digestive complications in this patient group and to anticipate their impact on nutritional and healthcare status, as malnutrition may contribute to neurological impairment.

The objective of this study is to analyse the prevalence of swallowing difficulties in children and adolescents with CP and their correlation with motor dysfunction and other comorbidities.

Material and methodsWe conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional, open study to evaluate the prevalence and severity of swallowing difficulties and to analyse nutritional status and its relationship with the degree of motor impairment in children and adolescents with CP followed up in 2016-2017 at the outpatient paediatric neurology consultation of a tertiary-level hospital in the Region of Madrid. Patients were evaluated during follow-up visits, according to an assessment protocol that collected the following data:

a. Demographic data: age, sex, topographical classification of CP (tetraplegia, hemiplegia, diplegia, etc), predominant motor disorder (spasticity, dyskinesia, ataxia, hypotonia, mixed, etc),11 and degree of functional impairment according to the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS). The latter instrument differentiates between 5 levels of motor impairment:

- -

Level I: no limitations (walks, runs, climbs stairs, etc). Impaired coordination.

- -

Level II: limitations walking on uneven surfaces or long distances. Needs support climbing stairs. Difficulties running and jumping.

- -

Level III: walks with a cane or crutches. Needs a wheelchair to travel long distances.

- -

Level IV: uses a walker at home. Pushed in a wheelchair in other situations.

- -

Level V: complete dependence for mobility.

b. Targeted medical history interviews were held to identify possible feeding alterations related to food intake (quantity and textures of foods), complementary feeding routes (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, etc), and whether or not the patient was dependent on caregivers for feeding.

c. Dysphagia screening: questions aiming to identify red flags for dysphagia and subsequently classify them.2 The main questions used were:

- 1

Are meal times stressful for the patient or caregivers?

- 2

Does the patient take longer than 40 minutes to eat?

- 3

Does the patient have a preference for any particular texture?

- 4

Does the patient present recurrent respiratory tract infections?

- 5

While eating, does the patient present changes in colouration (rubefaction/cyanosis), bouts of coughing or nausea, sialorrhoea, and/or conjunctival congestion?

d. Classification of dysphagia severity according to the Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS). The EDACS scale assesses functional capacity to eat and drink in children with CP. It is based on key characteristics associated with safety (aspiration and choking) and efficiency (amount of food lost and time taken to eat), and evaluates patients’ capacity to perform a range of processes related to feeding12,13:

- -

Neuromotor function: ability to bite, chew, and swallow.

- -

Management of different textures of foods and fluids.

- -

Respiration: risk of microaspiration, aspiration, or asphyxia.

According to these characteristics, the scale establishes 5 levels:

- -

Level I: eats and drinks safely and efficiently.

- -

Level II: eats and drinks safely but with some limitations to efficiency.

- -

Level III: eats and drinks with some limitations to safety; maybe limitations to efficiency.

- -

Level IV: eats and drinks with significant limitations to safety.

- -

Level V: unable to eat or drink safely. Tube feeding may be considered to provide nutrition.

The EDACS scale is a validated instrument and has been translated to Spanish; it may be downloaded free of cost at www.edacs.org.

e. Somatometric evaluation: always performed at the consultation by the same physician. Weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) were determined using a SECA 799 electronic column scale and a SECA 220 measuring rod. Patients who could not walk or were unable to stand were weighed using the double weighing method (weight of parent subtracted from combined weight of parent and child) and their length was estimated with the following formula14:

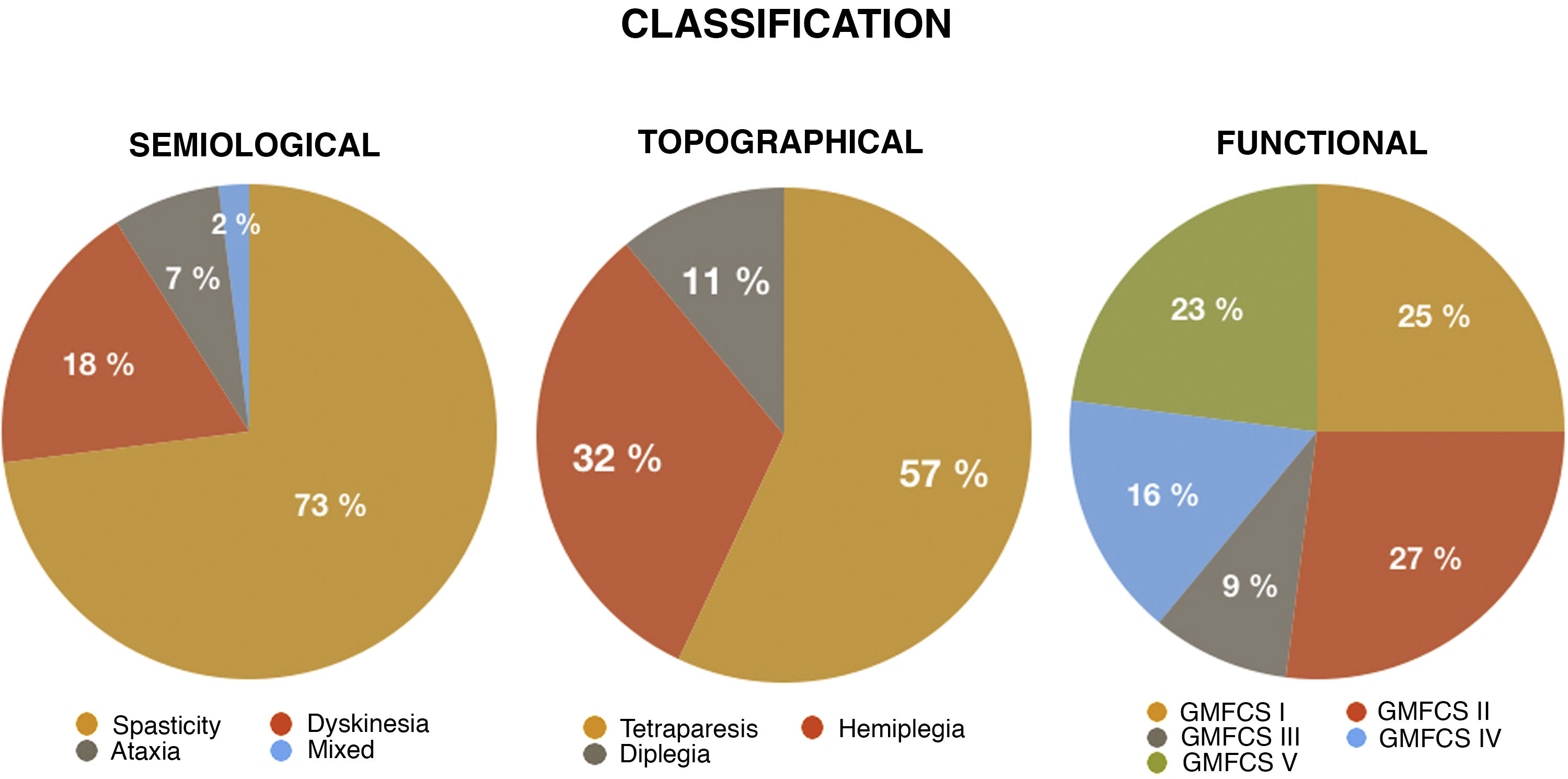

ResultsThe study included a total of 44 patients; 65.9% of patients were male, and mean age (standard deviation [SD]) was 9.34 (5) years (range, 3-21). The topographical classification of CP was tetraparesis in 57% of cases, hemiplegia in 32%, and diplegia in 11%. Regarding the predominant movement disorders, most patients presented spasticity, either as the only disorder (73%) or in the context of mixed CP (18%).

According to the GMFCS scale, half of our patients were classified into the first 2 levels. The remaining patients were classified as follows: 9% were level III, 16% were level IV, and 23% were level V.

Fig. 1 presents the distribution of different types of CP according to the different classification criteria used.

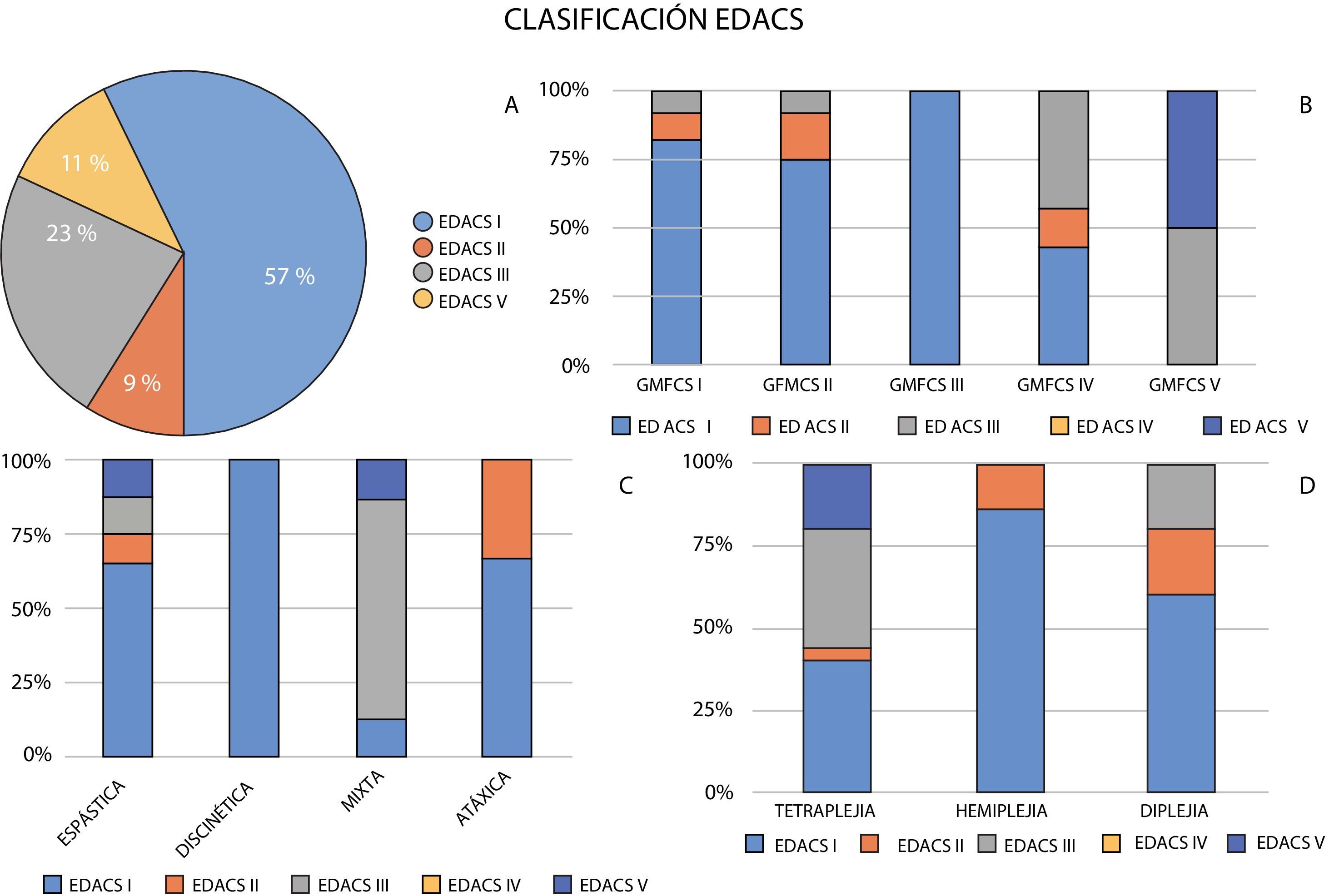

Regarding red flags for dysphagia, medical history interviews found that 57% of patients ate and drank safely and efficiently (EDACS level I). The remaining patients presented some alteration. Nine percent were classified as EDACS level II, 23% as EDACS level III, and the remaining 11% of patients were classified as EDACS level V.

With regard to CP topography, greater percentages of patients with more extensive motor involvement presented limitations for eating and drinking.

Among patients with tetraparesis, 40% were classified as EDACS level I, 4% as EDACS level II, 36% as EDACS level III, and 20% as EDACS level V. In the group of patients with diplegia, 60% were classified as EDACS level I, 20% as EDACS level II, and 20% as EDACS level III. Among patients with hemiplegia, 86% ate and drank safely and efficiently (EDACS level I), with only 14% presenting minor limitations in efficiency (EDACS level II).

In terms of predominant motor semiology, patients with several movement disorders (mixed CP) presented the greatest feeding difficulties (75% EDACS level III and 12.5% EDACS level V), followed by those with spasticity (12.5% EDACS level III and 12.5% EDACS level V). In the remaining groups, nearly all patients ate and drank safely and efficiently.

Fig. 2 shows the classification of patients with each type of CP according to the EDACS scale.

Distribution of levels of dysphagia according to the Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS) and their relationship with the type of cerebral palsy according to the predominant motor disorder, topographical distribution, and Gross Motor Function Classification System level (GMFCS).

Analysis of feeding difficulties (EDACS) and motor dysfunction (GMFCS) showed a certain correlation between both scales. Patients with greater feeding difficulties (higher EDACS levels) presented more severe functional impairment (higher GMFCS levels). Thus, while the majority of patients below level III on the GMFCS ate and drank safely (EDACS level I), 100% of patients classified as level V on the GMFCS presented feeding difficulties (EDACS level III or higher). Fifty percent of patients had problems with safety or limited feeding efficiency (EDACS level III), and the rest were unable to eat or drink safely (EDACS level V). Fig. 2 shows the distribution of EDACS levels for each GMFCS level.

According to somatometric values and the Quetelet index, the majority of patients were classified as underweight. Mean BMI was 17.63 kg/m2 (4.84); BMI values were lower among patients with higher EDACS levels and greater motor impairment according to GMFCS score. BMI was below 18.5 kg/m2 in 40% of patients with EDACS level I, 100% of those with EDACS level II, 50% of those with EDACS level III, and 80% of those with EDACS level V.

DiscussionCP is the most frequent cause of disability in childhood in developed countries. Its prevalence has increased in recent years, possibly due to improvements in medical treatment and care, follow-up protocols, and palliative care for patients with more severe CP, which have led to increased global life expectancy in this patient group.

Swallowing disorders are one of the most frequent comorbidities in patients with CP. Neurological damage causes neuromuscular dysfunction that may directly or indirectly result in oral motor disorders, pharyngo-oesophageal dyskinesia, and/or intestinal dysmotility. This may cause difficulty opening the mouth, poor coordination of sucking and chewing/swallowing, gastro-oesophageal reflux, etc, preventing the patient from eating and drinking correctly.

Similarly to other results reported in the literature, 43% of patients in our study presented some degree of limitation in safety and/or efficiency when eating or drinking.13 These difficulties were present in all forms of CP, regardless of the classification used, with the exception of patients with predominant dyskinesia.

As we would expect, the percentage of patients with feeding difficulties (EDACS level > 2) was greater among those with more severe motor impairment (60% of patients with tetraparesis) and more varied motor symptoms (87% of patients with mixed CP).

While clinical signs indicative of oropharyngeal dysphagia were more frequent and more severe in patients with higher GMFCS levels (100% of patients with GMFCS level V), eating and drinking difficulties were observed in patients at practically all GMFCS levels; this reflects the results of other studies in the literature.2,14,15

Eighteen percent of patients with GMFCS level I and up to 25% of those with GMFCS level II were classified as EDACS level II or III; this represents a considerable number of patients, if we take into account the potential consequences: higher risk of insufficient food intake and malnutrition.

Malnutrition is present in 40%-90% of all patients with CP. It may be accompanied by poor growth, micronutrient deficits, and osteopaenia, as well as poorer neurological prognosis.

In our study, BMI values indicated poorer nutritional status in patients with higher EDACS levels and poorer motor function according to the GMFCS. However, in the analysis of red flags for dysphagia, while the percentage of patients with BMI below 18.5 kg/m2 was directly proportional to EDACS levels (100% of patients with GMFCS level V), underweight patients were present in all EDACS levels (40% of patients with EDACS level I, 100% for EDACS level II, 50% for EDACS level III, and 80% for EDACS level V).

Despite its small size, we consider our sample to be homogeneous and representative of everyday clinical practice, as the patients included belong to a similar population in terms of the symptoms and dysfunction caused by CP. Therefore, we believe that these results are clinically relevant and should lead us to reflect on the importance of thorough medical history interviews and physical exploration to screen for these disorders in patients with CP, regardless of the degree of motor impairment.

Detection of feeding disorders enables early intervention on the affected function and prevention or treatment of the main associated comorbidities (malnutrition, microaspiration, recurrent infections, etc) that negatively affect these patients’ neurological status.6,7,15–18

Medical history interviews should include questions addressing the ability to bite, chew, and swallow and to manage different textures of foods and fluids, as well as red flags indicating dysphagia (changes in breathing while eating, hoarse voice, or history of recurrent pneumonia). This would enable us to identify the risk of microaspiration or asphyxia and refer the patient to the relevant specialist, who may confirm this suspicion with the appropriate complementary studies (mainly videofluoroscopy, which provides a dynamic view of the oropharyngeal phase, or flexible endoscopy).19,20

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.