Valproate-induced hyperammonaemic encephalopathy (VHE) is a rare entity characterised by acute or subacute alterations in the level of consciousness, confusion, and focal neurological signs, progressing to seizures, ataxia, stupor, and coma.1 Most patients show high blood ammonia levels, with no evidence of liver failure; they also display electroencephalography (EEG) alterations, typically with generalised slowing of delta activity.1 Although seizures are a characteristic symptom of VHE, only 2 cases have been reported of valproate-induced status epilepticus.2,3 We describe the case of a patient who developed non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) in the context of VHE.

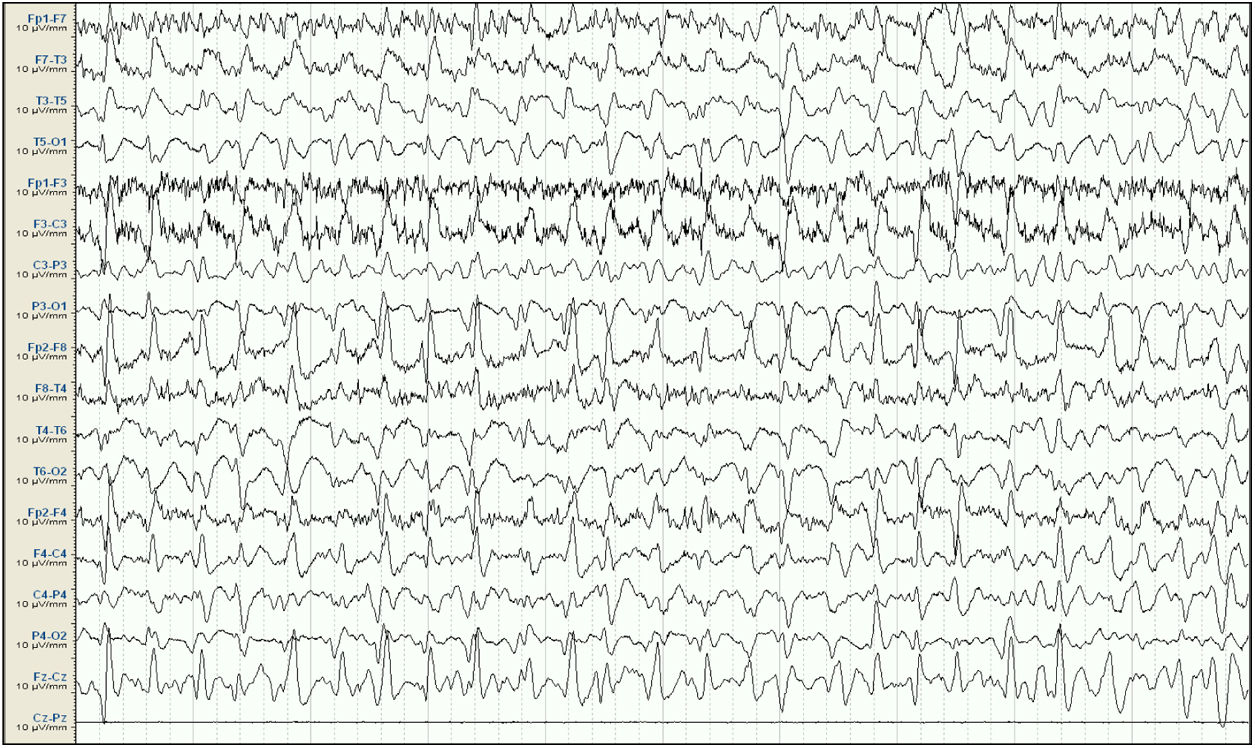

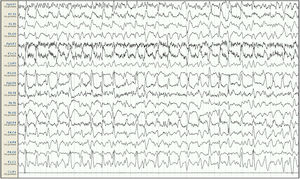

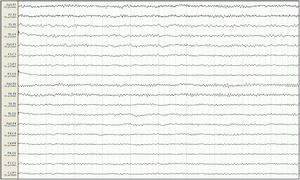

Our patient was a 57-year-old woman with history of chronic kidney disease secondary to interstitial nephritis, under treatment with haemodialysis since 2007; she had undergone kidney transplant in 2009 but presented chronic renal transplant rejection, and was receiving prednisone dosed at 5mg/24h. Six months before admission, she presented a first episode of generalised tonic-clonic seizures after a dialysis session. Laboratory analyses and a head CT scan performed at the emergency department revealed no significant alterations; the suspected cause of the episode was metabolic imbalance in the context of dialysis. The patient experienced a second episode a month later. Again, no significant metabolic alterations were observed; however, an EEG study revealed epileptiform discharges in the right temporal lobe. Treatment was started with valproate dosed at 500mg/12h, and she was referred to the neurology department for further study and follow-up. She subsequently presented another episode and was attended at the emergency department; levetiracetam was added at 500mg/12h. Approximately one month before admission, the patient presented agitation, hetero-aggressiveness, and suicidal ideation; she was admitted to the psychiatry department, where treatment with olanzapine and lorazepam was started and the dose of levetiracetam was reduced. A week after admission, she presented fluctuations in the level of alertness and recurrent generalised tonic-clonic seizures without complete recovery of the level of consciousness between seizures, and was therefore admitted to the intensive care unit. The examination revealed a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3; isochoric, normoreactive medium-sized pupils; and fluctuating episodes of irregular, multifocal clonic movements of the limbs. Orotracheal intubation was performed and the patient received intravenous antiepileptic treatment with valproate and levetiracetam, which resolved the motor alterations. Psychiatric treatment was suspended. An EEG study revealed a pattern compatible with NCSE (Fig. 1), and lacosamide was added to the treatment regime. A laboratory analysis and a head CT scan revealed no significant alterations, with no changes detected in the patient's usual kidney function. A follow-up EEG study revealed no significant changes; perampanel was added to her treatment and the doses of midazolam and propofol (added to the treatment regime when the patient was intubated) were progressively increased. In view of the lack of EEG abnormalities, a CSF analysis was performed, revealing no alterations in biochemistry, cytology, or PCR results for neurotropic viruses; the patient also tested negative for antineuronal antibodies and oligoclonal bands. An autoimmune study of the serum yielded normal results. A follow-up EEG study revealed a burst-suppression pattern with sustained, sharp waves. Subsequent laboratory analyses revealed valproate levels persistently below the therapeutic range and elevated serum ammonia levels (65μmol/L; reference range: 9-35); ammonia levels had not been measured previously. Valproate was therefore discontinued 8 days after admission to the intensive care unit. Follow-up EEG studies showed progressive improvement, with less frequent acute activity; sedatives were gradually withdrawn and the EEG pattern was nearly normal after 7 days (Fig. 2); ammonia levels progressively decreased and level of consciousness improved. The patient fully recovered, presenting no further episodes.

Baseline electroencephalography (international 10-20 system, longitudinal montage). Attenuation of background activity, which is substituted by diffuse epileptiform discharges predominantly in the right frontal and central areas, appearing persistently throughout the reading; this is compatible with status epilepticus. Lack of signal from the Cz-Pz derivation for technical reasons.

VHE is a rare complication of treatment with valproate. It occurs when valproate interferes with the urea cycle, inhibiting carbamylphosphate synthetase I. Valproate is extensively metabolised in the liver through 3 pathways. High doses or long-term treatment with the drug result in higher levels of metabolites, such as propionic acid and 2-propyl-4-pentenoic acid, which decrease levels of N-acetylglutamate, a cofactor of carbamylphosphate synthetase I; this inhibits the enzyme and interferes with the urea cycle, causing hyperammonaemia.4 Although the exact pathophysiological mechanism of VHE is not fully understood, we do know that excess ammonia crosses the blood-brain barrier and inhibits intracellular glutamate uptake; increased NMDA receptor activity due to elevated extracellular glutamate levels causes excitotoxicity, ultimately leading to encephalopathy.4,5 It has also been hypothesised that increased astrocytic glutamine production due to the elimination of excess ammonia in the brain increases intracellular osmolarity and an intracellular shift of water, leading to astrocyte swelling and cerebral oedema.4,6

Several risk factors for VHE have been identified, such as antiepileptic polytherapy with pentobarbital, phenytoin, topiramate, or levetiracetam combined with valproate7–9; other factors include carnitine deficiency and urea cycle disorders.5 However, elevated serum valproate levels are not directly correlated with VHE10; in fact, our patient displayed low valproate levels.

Diagnosis of this entity is based on the presence of acute symptoms of encephalopathy and high ammonia levels in the context of treatment with valproate. Patients treated with valproate, and particularly those also taking other antiepileptics, may present asymptomatic hyperammonaemia.11 However, VHE should be considered in patients treated with valproate who present subacute or chronic mild cognitive impairment or psychiatric symptoms, as the condition may not always be evident, significantly hindering diagnosis, as in the case presented here. In this context, differential diagnosis should include other subacute encephalopathies (metabolic, toxic, infectious, autoimmune, etc), which were ruled out in our patient. A diagnosis of NCSE should also be ruled out in patients presenting impaired level of consciousness, with an EEG study and thorough differential diagnosis.

Only 2 cases of valproate-induced NCSE have been published to date: the first case was that of a patient with acute symptoms of low level of consciousness and multifocal myoclonus, presenting 4 days after onset of valproate treatment; EEG findings were compatible with NCSE.2 The second case describes a patient with drug-resistant focal epilepsy who, after rapid uptitration of valproate to 1600mg in 5 days, developed fluctuating confusional state associated with episodes of staring and complete unresponsiveness; this patient also presented EEG results compatible with NCSE but presented normal ammonia levels.3 The difference between our patient and the 2 cases described in the literature is that in our case, treatment with valproate had started months before the episode and the dose had remained stable; this delayed diagnosis in our patient. The lack of pathological findings from complementary tests, with the exception of elevated ammonia levels, and the improvements seen in EEG after discontinuation of valproate treatment (no other treatment decisions were made simultaneously) suggest VHE as the most likely diagnosis. Furthermore, neither our patient nor the first case mentioned above2 presented markedly elevated ammonia levels; no correlation has been found between clinical severity and higher ammonia levels.1

In conclusion, we present a rare case of NCSE secondary to VHE. Though rare, this entity should be included in the differential diagnosis of refractory NCSE of no evident cause in patients treated with valproate.

FundingThis study received no public or private funding.

Please cite this article as: Viloria Alebesque A, Montes Castro N, Arcos Sánchez C, Vicente Gordo D. Estatus epiléptico no convulsivo secundario a encefalopatía hiperamonémica inducida por valproato. Neurología. 2020;35:603–606.