The recurrent c.625G>A (p.Glu209Lys) pathogenic variant of the PACS2 gene has recently been reported to be the causal agent of developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 66 (DEE66; MIM #610423) in 15 patients with predominantly neonatal-onset epilepsy, facial dysmorphism, and cerebellar dysgenesis, which may also be associated with such developmental disorders as intellectual disability, autistic spectrum disorders, haematological alterations, and/or distal limb abnormalities.1,2 Since the condition was first described, only one case with a similar phenotype and a different PACS2 variant has been reported.3 In 2012, 2 cases were reported of intellectual disability due to a recurrent mutation in the PACS1 gene sharing clinical characteristics with the previously reported cases (hypotonia, epilepsy, facial dysmorphism).4

The PACS2 gene is expressed in different tissues and encodes the multifunctional PACS2 protein, which plays a major role in the interaction between the endoplasmic reticulum membrane and the mitochondria. It acts as a metabolic switch involved in trafficking and signalling between these membranes, as well as nuclear gene expression in response to catabolic or anabolic signals.5,6 We present a new case of the recurrent variant of PACS2, detected in 15 of the 16 cases of DEE66 reported worldwide.

Our patient was a 3-year-old girl with no relevant medical history; she was the second child of healthy, non-consanguineous parents of Bolivian descent. She was referred to our hospital’s medical genetics department by the paediatric neurology department at the age of 16 months due to polydactyly, facial dysmorphism, and epilepsy. The patient was born after a spontaneous, uneventful, full-term pregnancy. Birth weight was 4000 g; resuscitation was not required and the neonatal period was normal. The blood spot and otoacoustic emission tests yielded normal results. She underwent surgery to treat postaxial polydactyly in both feet, with no complications. Developmentally, she presents no feeding problems and shows normal growth at 3 years of age: weight, 13.9 kg (p63); height, 89 cm (p36); head circumference, 47 cm (p10). Her dysmorphic features overlap with those previously described (Fig. 1).

Phenotype of our patient at the age of 3 years. Coarse facial features, mild hypertelorism, arched eyebrows with mild synophrys, low nasal bridge, short nose, anteverted nares, thin upper lip with downward oral commissures, mild retrognathia, mild brachydactyly, and surgically corrected postaxial polydactyly in both feet.

At 3 months of age, our patient began to present seizures, consisting of right-sided deviation of the head and eyes, generalised hypertonia, and dystonic posturing of the limbs; levetiracetam achieved no response and valproic acid exacerbated symptoms. An emergency head CT scan revealed no alterations; the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit due to status epilepticus. We started perfusion with midazolam and phenytoin; after seizure control, phenytoin was switched for zonisamide, which the patient continues receiving at present. EEG at admission revealed diffuse background slowing, with no focal abnormalities or any other type of epileptiform activity. EEG findings at 24 hours were similar but less marked; a month later, the EEG trace was completely normal. However, at 5 months of age she was readmitted due to exacerbation of seizures; she presented additional episodes at ages 24 and 30 months. The patient has remained seizure-free since then, with all interictal EEG studies showing normal results.

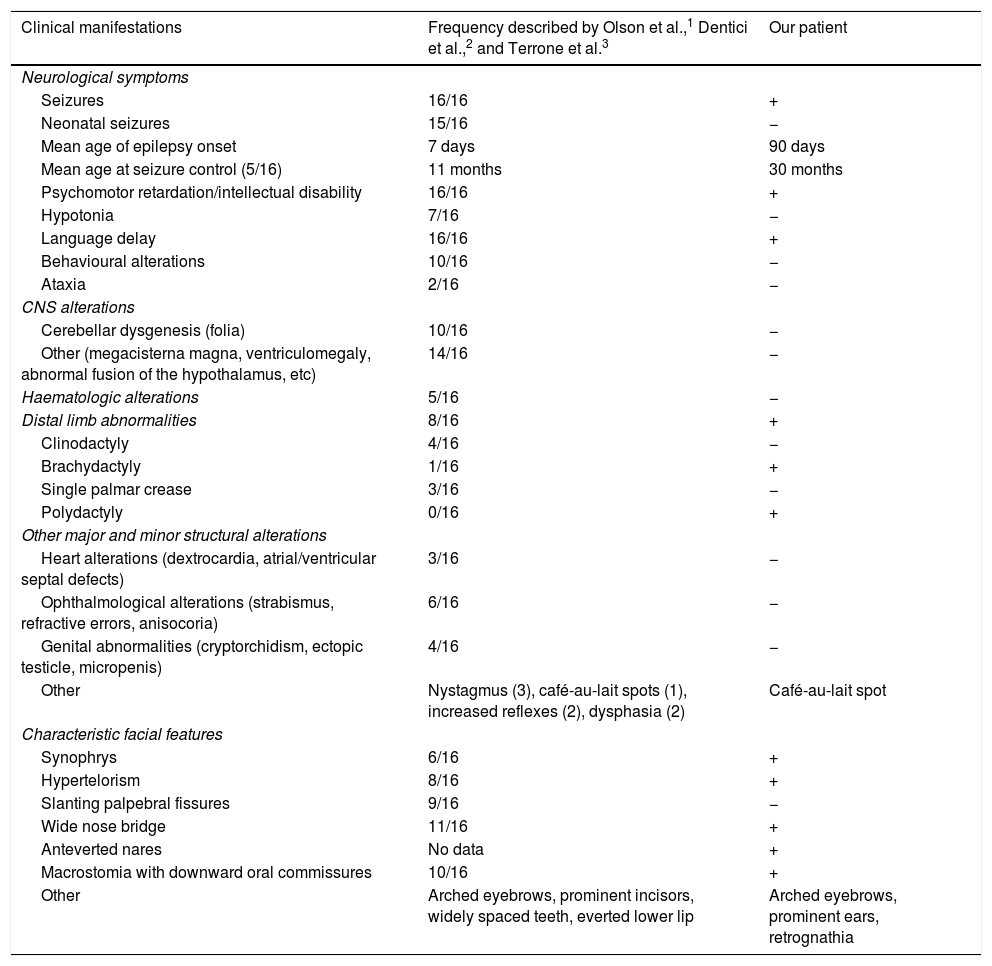

Our patient presented psychomotor retardation; at age 3 years and 6 months, she presented a developmental age of 15-18 months in the areas assessed, according to the modified Vaughan scale. Expressive language was the most severely affected area, with the patient also presenting occasional episodes of self- and hetero-aggression. She is currently being followed up at an early childhood special needs centre and attends mainstream school, where she receives tailored support. Table 1 compares the clinical features of our case against those from previously reported cases.

Clinical characteristics of our patient and the previously published cases.

| Clinical manifestations | Frequency described by Olson et al.,1 Dentici et al.,2 and Terrone et al.3 | Our patient |

|---|---|---|

| Neurological symptoms | ||

| Seizures | 16/16 | + |

| Neonatal seizures | 15/16 | − |

| Mean age of epilepsy onset | 7 days | 90 days |

| Mean age at seizure control (5/16) | 11 months | 30 months |

| Psychomotor retardation/intellectual disability | 16/16 | + |

| Hypotonia | 7/16 | − |

| Language delay | 16/16 | + |

| Behavioural alterations | 10/16 | − |

| Ataxia | 2/16 | − |

| CNS alterations | ||

| Cerebellar dysgenesis (folia) | 10/16 | − |

| Other (megacisterna magna, ventriculomegaly, abnormal fusion of the hypothalamus, etc) | 14/16 | − |

| Haematologic alterations | 5/16 | − |

| Distal limb abnormalities | 8/16 | + |

| Clinodactyly | 4/16 | − |

| Brachydactyly | 1/16 | + |

| Single palmar crease | 3/16 | − |

| Polydactyly | 0/16 | + |

| Other major and minor structural alterations | ||

| Heart alterations (dextrocardia, atrial/ventricular septal defects) | 3/16 | − |

| Ophthalmological alterations (strabismus, refractive errors, anisocoria) | 6/16 | − |

| Genital abnormalities (cryptorchidism, ectopic testicle, micropenis) | 4/16 | − |

| Other | Nystagmus (3), café-au-lait spots (1), increased reflexes (2), dysphasia (2) | Café-au-lait spot |

| Characteristic facial features | ||

| Synophrys | 6/16 | + |

| Hypertelorism | 8/16 | + |

| Slanting palpebral fissures | 9/16 | − |

| Wide nose bridge | 11/16 | + |

| Anteverted nares | No data | + |

| Macrostomia with downward oral commissures | 10/16 | + |

| Other | Arched eyebrows, prominent incisors, widely spaced teeth, everted lower lip | Arched eyebrows, prominent ears, retrognathia |

The paediatric neurology department conducted the following complementary tests during follow-up: brain MRI and abdominal ultrasound (neonatal period), with no pathological findings; cardiology and ophthalmology examinations, with normal results (no signs of retinopathy); 60 K array-CGH analysis; and blood and urine metabolic screening including asialotransferrin, sterols, amino acids, organic acids, lactate/pyruvate, acylcarnitines, sulfites, and purine metabolism, with normal results. The patient was assessed by the genetics department due to suspicion of a genetic disorder, possibly a ciliopathy, due to the combination of psychomotor retardation, polydactyly, brachydactyly, and facial dysmorphism. A next-generation sequencing analysis of the associated genes found no candidate variants, and hearing tests (brainstem auditory evoked potentials and audiometry test) detected no alterations. Clinical exome sequencing identified the previously described pathogenic variant in PACS2. Our patient’s parents could not undergo genetic studies since they were not registered as residents of the region where our centre is located.

We present a new case of DEE66 due to PACS2 pathogenic variant c.625G>A, manifesting with milder symptoms than reported in most cases due to later onset of epilepsy and lack of cerebellar dysgenesis. Our case expands the phenotype of the condition, as the patient presented polydactyly. The clinical worsening observed after onset of treatment with valproic acid may be linked to the function of the PACS2 protein; use of this drug should therefore be questioned.

Our case confirms the involvement of PACS2 in the pathogenesis of intellectual disability and epileptic encephalopathy, and underscores the usefulness of clinical exome sequencing for the diagnosis of recently-described, and probably underdiagnosed, rare, complex phenotypes.

Our patient presented the same variant as 15 of the 16 reported cases of DEE66, which confirms that this is a recurrent variant.

The PACS2 gene should be included in panels for epileptic encephalopathy and cerebellar dysgenesis, and in patients with suspected ciliopathies and/or alterations in the PACS1 gene.

FundingThis study has received no funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank our patient’s family for making the study possible.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Soler MJ, Serrano-Antón AT, López-González V, Guillén-Navarro E. Nuevo caso con la variante patogénica recurrente c.625G>A en el gen PACS2: expansión del fenotipo. Neurología. 2021;36:716–719.