The objective of this study was to analyse the impact of alcohol use disorders (AUD) in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) in terms of in-hospital mortality, extended hospital stays, and overexpenditures.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective observational study in a sample of MS patients obtained from minimal basic data sets from 87 Spanish hospitals recorded between 2008 and 2010. Mortality, length of hospital stays, and overexpenditures attributable to AUD were calculated. We used a multivariate analysis of covariance to control for such variables as age and sex, type of hospital, type of admission, other addictions, and comorbidities.

ResultsThe 10249 patients admitted for MS and aged 18-74 years included 215 patients with AUD. Patients with both MS and AUD were predominantly male, with more emergency admissions, a higher prevalence of tobacco or substance use disorders, and higher scores on the Charlson comorbidity index. Patients with MS and AUD had a very high in-hospital mortality rate (94.1%) and unusually lengthy stays (2.4 days), and they generated overexpenditures (1116.9euros per patient).

ConclusionsAccording to the results of this study, AUD in patients with MS results in significant increases in-hospital mortality and the length of the hospital stay and results in overexpenditures.

El objetivo de este estudio es el análisis del impacto de los trastornos asociados al consumo de alcohol (TCA) en los pacientes con esclerosis múltiple (EM), en términos de exceso de mortalidad intrahospitalaria, prolongación de estancias y sobrecostes.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo de una muestra de pacientes ingresados con EM recogidos en los conjuntos mínimos básicos de datos de 87 hospitales españoles durante el periodo 2008-2010. Se calculó la mortalidad, la prolongación de estancias y los sobrecostes atribuibles a los TCA controlando mediante análisis multivariado de la covarianza variables como la edad y el sexo, el tipo de hospital, el tipo de ingreso, otros trastornos adictivos y las comorbilidades.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 10.249 ingresos por EM de 18 a 74 años de edad, entre los cuales hubo 215 pacientes con TCA. Los ingresos con EM y TCA fueron predominantemente varones, mayor frecuencia de ingresos urgentes, con mayor prevalencia de trastornos por tabaco y drogas y con índices de comorbilidad de Charlson más elevados. Los pacientes con EM y TCA presentaron importantes excesos de mortalidad (94,1%), prolongación indebida de estancias (2,4 días) y sobrecostes por alta (1.116,9euros).

ConclusionesDe acuerdo a los resultados de este estudio, los TCA en pacientes con EM aumentaron significativamente la mortalidad, la duración de la estancia hospitalaria y sus costes.

The mortality rate of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) is higher than that of the general population; life expectancy of these patients is 7-14 years shorter.1,2 In many cases, death is due to causes which are unrelated to the disease and frequent among the general population: cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, infections, and injury (including self-harm).3–6 Both chronic and acute alcohol use disorders (AUD) may worsen the progression of MS. In these patients, AUDs may promote or aggravate such conditions as obesity, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, pancreatitis, cirrhosis, stroke, and tumours.7 The prevalence of anxiety and depression disorders,8–11 suicidal ideation, and self-harm is also higher among patients with MS and AUDs.8,9,12,13 AUDs are usually associated with tobacco use, and many of the disorders cited may worsen when patients with MS are heavy smokers or have nicotine dependence.14,15

AUDs may worsen cognitive impairment in patients with MS16,17 and are associated with poorer treatment compliance, which results in more severe disease progression.18,19

Despite the above, no studies have addressed the impact of AUDs on hospitalised patients with MS in Spain in terms of alcohol-attributable mortality, extended hospital stays, and overexpenditure.

In-hospital outcomes may also be influenced by such other variables as age, sex, hospital, type of admission (emergency vs scheduled), presence of other addictions, and comorbidities.20–24 Therefore, any study aiming to evaluate the impact of AUDs on hospitalised patients with MS should consider the potential impact of confounding and the interaction effects of these predictive variables.

We gathered data from a sample of patients with MS, aged 18-74 years, from 87 Spanish centres, who were admitted to hospital between 2008 and 2010. We attempted to control for such confounding and interaction variables as age, sex, type of hospital, type of admission, concomitant addictions, and comorbidities.

The purpose of this study is to analyse the potential impact of AUDs on mortality, extended hospital stays, and overexpenditure for hospitalised patients with MS.

Patients and methodsStudy designWe conducted a retrospective observational study using a sample of patients from Spanish hospitals.

SampleTo ensure that the sample was representative of Spain and of every autonomous community, and accounting for the stratification of hospitals into groups (according to size and complexity) proposed by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality,25 we applied stratified sampling to select patients from 87 Spanish hospitals from every autonomous community.

Based on written and electronic data from the patients’ clinical histories, diagnoses and procedures were coded according to the ninth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9). Data were coded and recorded in the database by specialised staff. This type of database, called a minimum basic dataset (MBDS), contains demographic data, admission and discharge dates, type of admission and discharge, main and secondary diagnosis, external causes, and procedures; data are coded using the ICD-9. The database also uses the diagnosis-related group (DRG) system; hospitals are grouped by size and the type of care they provide.25

VariablesPresence of ICD-9 code 340 for any of the MBDS diagnostic codes was defined as MS.26 Patients transferred to other centres were excluded.

The study only included patients aged 18-74 years. As an indicator of comorbidity, we calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)27 for each comorbidity using the ICD-9 codes proposed by Quan et al.28 AUDs were defined as problems associated with excessive alcohol consumption, either sporadic or chronic, identified with the following ICD-9 codes: alcohol dependence syndrome (303.00-303.93), non-dependent alcohol abuse (305.00-305.03), alcohol-induced mental disorders (291.0-291.9), alcoholic polyneuropathy (357.5), alcoholic cardiomyopathy (425.5), alcoholic gastritis (535.30-535.31), alcohol-induced liver damage (571.0-571.3), excessive blood level of alcohol (790.3), and toxic effect of alcohol and accidental poisoning by alcohol (980.0-980.9 and E860.0-E860.9).29 We also used the ICD-9 codes for tobacco and other drug use.29

Hospitals were divided into 5 groups by size and type of care according to the classification of the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality25; this step was essential to control for confounding and to calculate care costs.

Data analysisThe main purpose of the study was to determine the mortality rate, hospitalisation time, and hospital costs associated with AUDs in patients with MS. Costs were calculated using the hospital costs of each DRG, stratified by hospital group, based on the estimates published by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality for the years 2008-2010.

A bivariate analysis was performed to examine the association between MS and AUD, on the one hand, and sex, type of admission, and other addictions and comorbidities, on the other; we used the chi-square and t tests, or their non-parametric versions. To minimise confounding, we performed a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) to determine the effect of AUDs on in-hospital mortality, duration of hospitalisation, and hospital costs in patients with MS. The requirements of continuous variables were verified and data were adjusted for age, sex, type of admission, addictions, hospital group, and health status (using the CCI) after selecting the model that best fitted the data. Statistical significance was set at P<.0001 due to the sample size and the fact that multiple comparisons were conducted. We calculated the adjusted mean of each dependent variable (mortality, hospitalisation time in days, costs at discharge) in patients with MS with and without AUDs, and evaluated the differences between both groups. Statistical analysis was performed with version 14.1 of the STATA/MP statistics software.

The study design and the analysis and presentation of results were based on the recommendations of the STROBE statement for observational studies.30

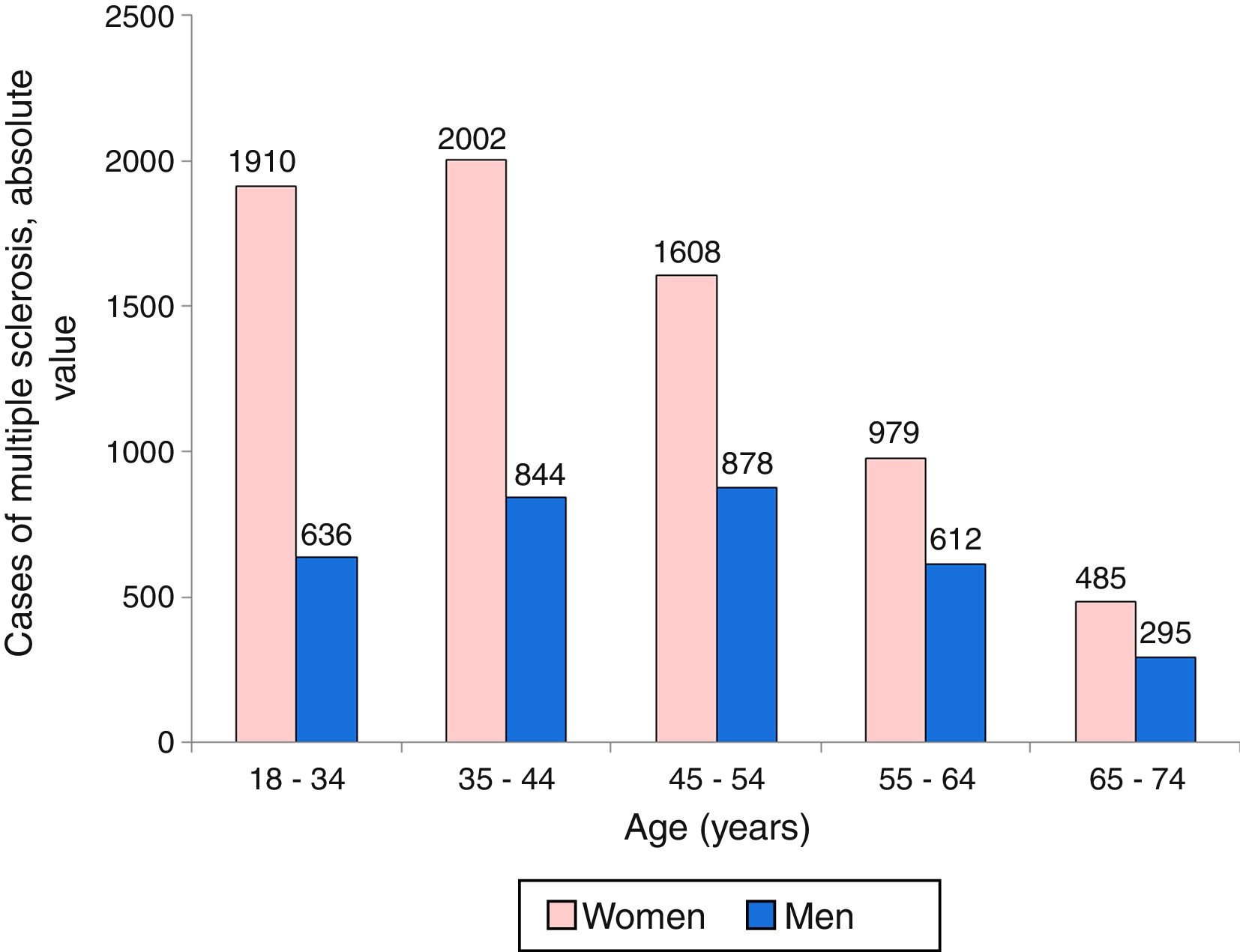

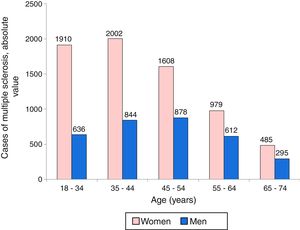

ResultsPatient characteristicsWe identified 10249 admissions due to MS: 6984 (68.1%) were women and 3265 (31.9%) were men. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of admissions by sex and age group. Most admissions of women with MS corresponded to the age group 35-44 years, followed by age groups 18-34 years and 45-54 years. Among men, admissions corresponded mainly to the age group 45-54 years, followed by groups 35-44 and 18-34 years.

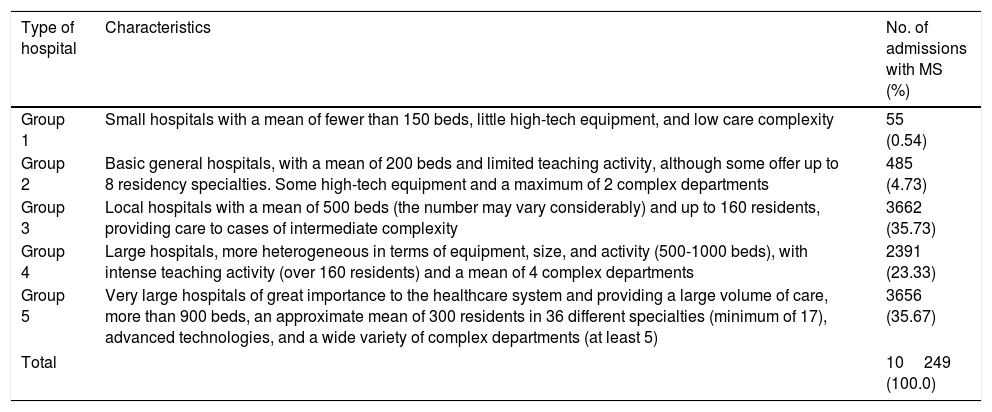

Table 1 shows the distribution of cases of MS in each group of hospitals and the characteristics of each type of centre.

Number of patients with multiple sclerosis admitted to different types of hospitals (classification of hospitals by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality).

| Type of hospital | Characteristics | No. of admissions with MS (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Small hospitals with a mean of fewer than 150 beds, little high-tech equipment, and low care complexity | 55 (0.54) |

| Group 2 | Basic general hospitals, with a mean of 200 beds and limited teaching activity, although some offer up to 8 residency specialties. Some high-tech equipment and a maximum of 2 complex departments | 485 (4.73) |

| Group 3 | Local hospitals with a mean of 500 beds (the number may vary considerably) and up to 160 residents, providing care to cases of intermediate complexity | 3662 (35.73) |

| Group 4 | Large hospitals, more heterogeneous in terms of equipment, size, and activity (500-1000 beds), with intense teaching activity (over 160 residents) and a mean of 4 complex departments | 2391 (23.33) |

| Group 5 | Very large hospitals of great importance to the healthcare system and providing a large volume of care, more than 900 beds, an approximate mean of 300 residents in 36 different specialties (minimum of 17), advanced technologies, and a wide variety of complex departments (at least 5) | 3656 (35.67) |

| Total | 10249 (100.0) | |

MS: multiple sclerosis.

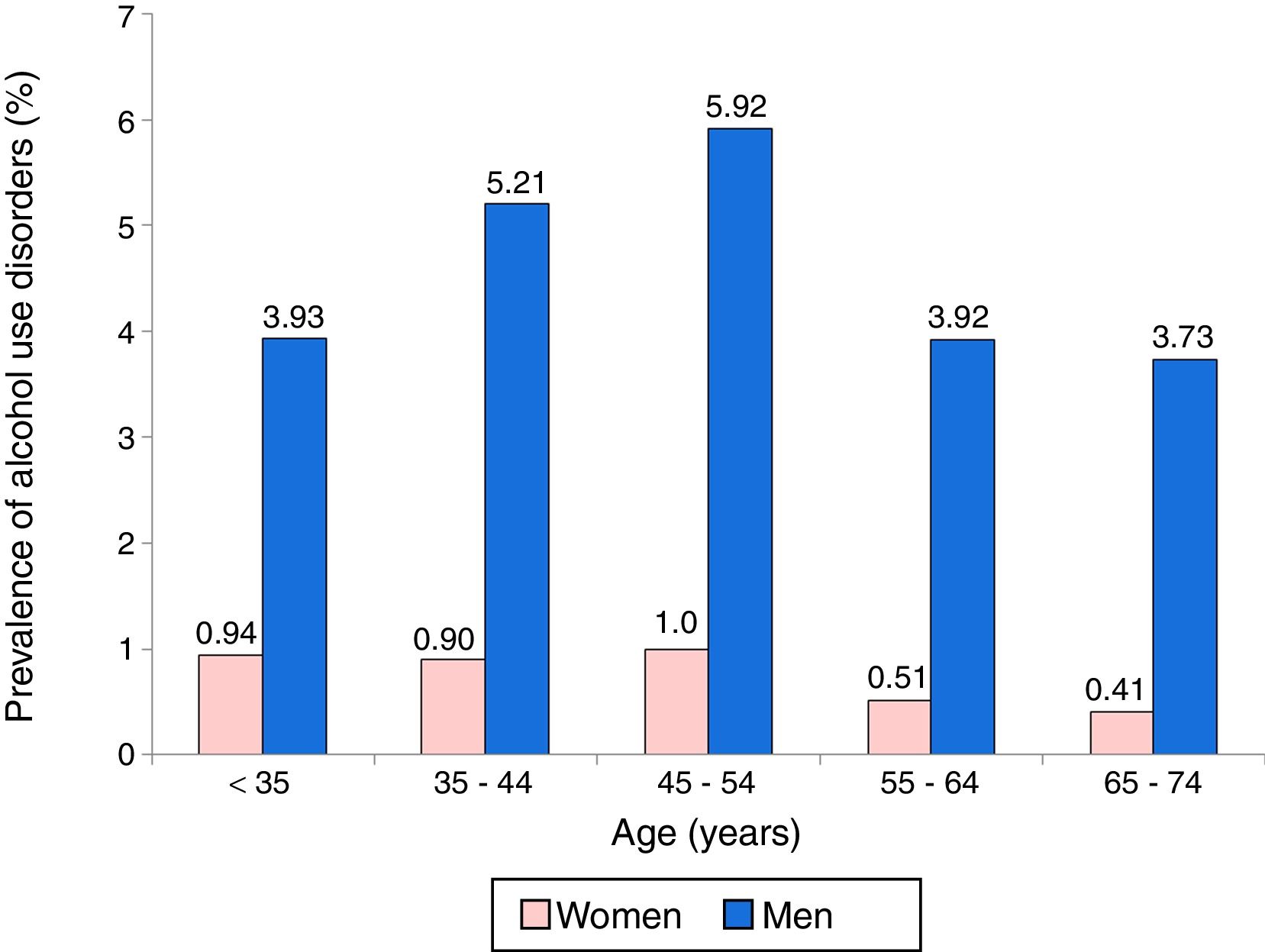

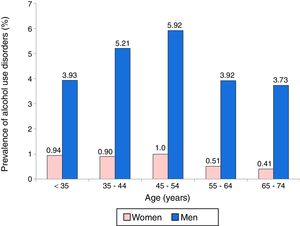

A total of 215 patients with MS had AUDs (2.1%); these were predominantly men (156 [4.8%] vs 59 women [0.8%]). Fig. 2 shows the distribution of patients with MS and AUDs by age and sex. AUDs were more frequent among men, especially in the age group 45-54 years, followed by the group of patients aged 35-44 years. Among women, prevalence of AUDs was higher in the 45-54 age group and the 18-34 year group.

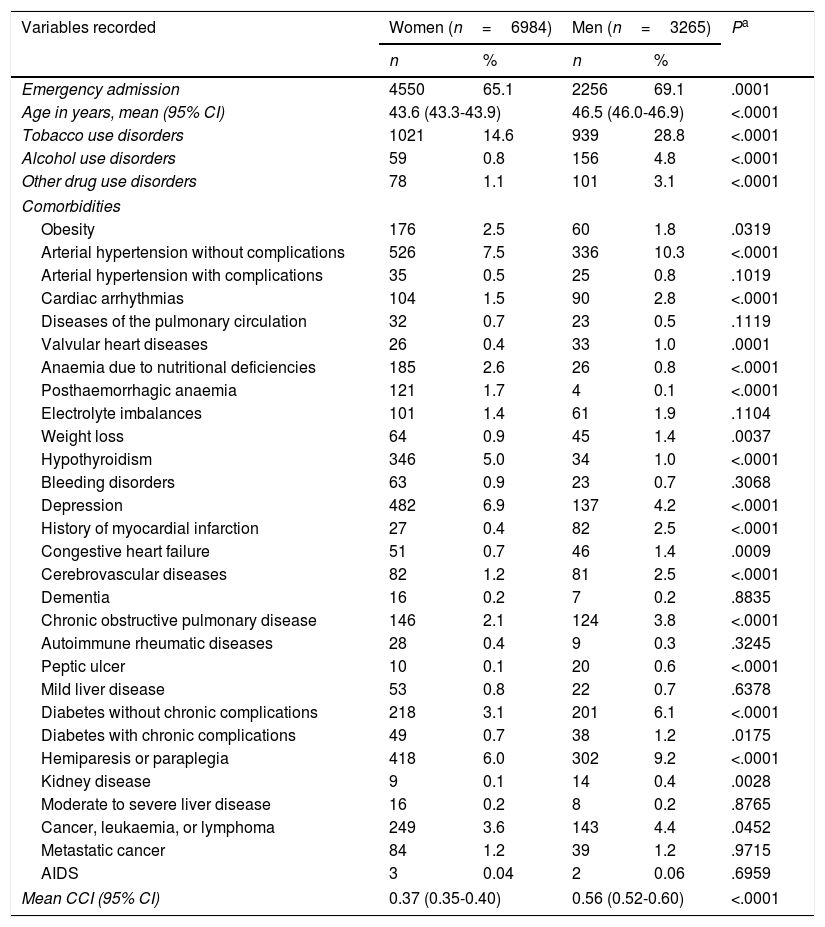

Table 2 summarises patient characteristics by sex. Male patients were older than women, caused more emergency admissions, and had a higher prevalence of addictions (tobacco use disorders, 28.8%; AUDs 4.8%; other drug use disorders, 3.1%). Men also had higher prevalence of several of the comorbidities analysed at admission: arterial hypertension, arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peptic ulcer, diabetes, and hemiparesis or paraplegia; they also displayed higher CCI scores.

Characteristics of patients admitted with MS, by sex.

| Variables recorded | Women (n=6984) | Men (n=3265) | Pa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Emergency admission | 4550 | 65.1 | 2256 | 69.1 | .0001 |

| Age in years, mean (95% CI) | 43.6 (43.3-43.9) | 46.5 (46.0-46.9) | <.0001 | ||

| Tobacco use disorders | 1021 | 14.6 | 939 | 28.8 | <.0001 |

| Alcohol use disorders | 59 | 0.8 | 156 | 4.8 | <.0001 |

| Other drug use disorders | 78 | 1.1 | 101 | 3.1 | <.0001 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Obesity | 176 | 2.5 | 60 | 1.8 | .0319 |

| Arterial hypertension without complications | 526 | 7.5 | 336 | 10.3 | <.0001 |

| Arterial hypertension with complications | 35 | 0.5 | 25 | 0.8 | .1019 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 104 | 1.5 | 90 | 2.8 | <.0001 |

| Diseases of the pulmonary circulation | 32 | 0.7 | 23 | 0.5 | .1119 |

| Valvular heart diseases | 26 | 0.4 | 33 | 1.0 | .0001 |

| Anaemia due to nutritional deficiencies | 185 | 2.6 | 26 | 0.8 | <.0001 |

| Posthaemorrhagic anaemia | 121 | 1.7 | 4 | 0.1 | <.0001 |

| Electrolyte imbalances | 101 | 1.4 | 61 | 1.9 | .1104 |

| Weight loss | 64 | 0.9 | 45 | 1.4 | .0037 |

| Hypothyroidism | 346 | 5.0 | 34 | 1.0 | <.0001 |

| Bleeding disorders | 63 | 0.9 | 23 | 0.7 | .3068 |

| Depression | 482 | 6.9 | 137 | 4.2 | <.0001 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 27 | 0.4 | 82 | 2.5 | <.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 51 | 0.7 | 46 | 1.4 | .0009 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 82 | 1.2 | 81 | 2.5 | <.0001 |

| Dementia | 16 | 0.2 | 7 | 0.2 | .8835 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 146 | 2.1 | 124 | 3.8 | <.0001 |

| Autoimmune rheumatic diseases | 28 | 0.4 | 9 | 0.3 | .3245 |

| Peptic ulcer | 10 | 0.1 | 20 | 0.6 | <.0001 |

| Mild liver disease | 53 | 0.8 | 22 | 0.7 | .6378 |

| Diabetes without chronic complications | 218 | 3.1 | 201 | 6.1 | <.0001 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 49 | 0.7 | 38 | 1.2 | .0175 |

| Hemiparesis or paraplegia | 418 | 6.0 | 302 | 9.2 | <.0001 |

| Kidney disease | 9 | 0.1 | 14 | 0.4 | .0028 |

| Moderate to severe liver disease | 16 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.2 | .8765 |

| Cancer, leukaemia, or lymphoma | 249 | 3.6 | 143 | 4.4 | .0452 |

| Metastatic cancer | 84 | 1.2 | 39 | 1.2 | .9715 |

| AIDS | 3 | 0.04 | 2 | 0.06 | .6959 |

| Mean CCI (95% CI) | 0.37 (0.35-0.40) | 0.56 (0.52-0.60) | <.0001 | ||

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index.

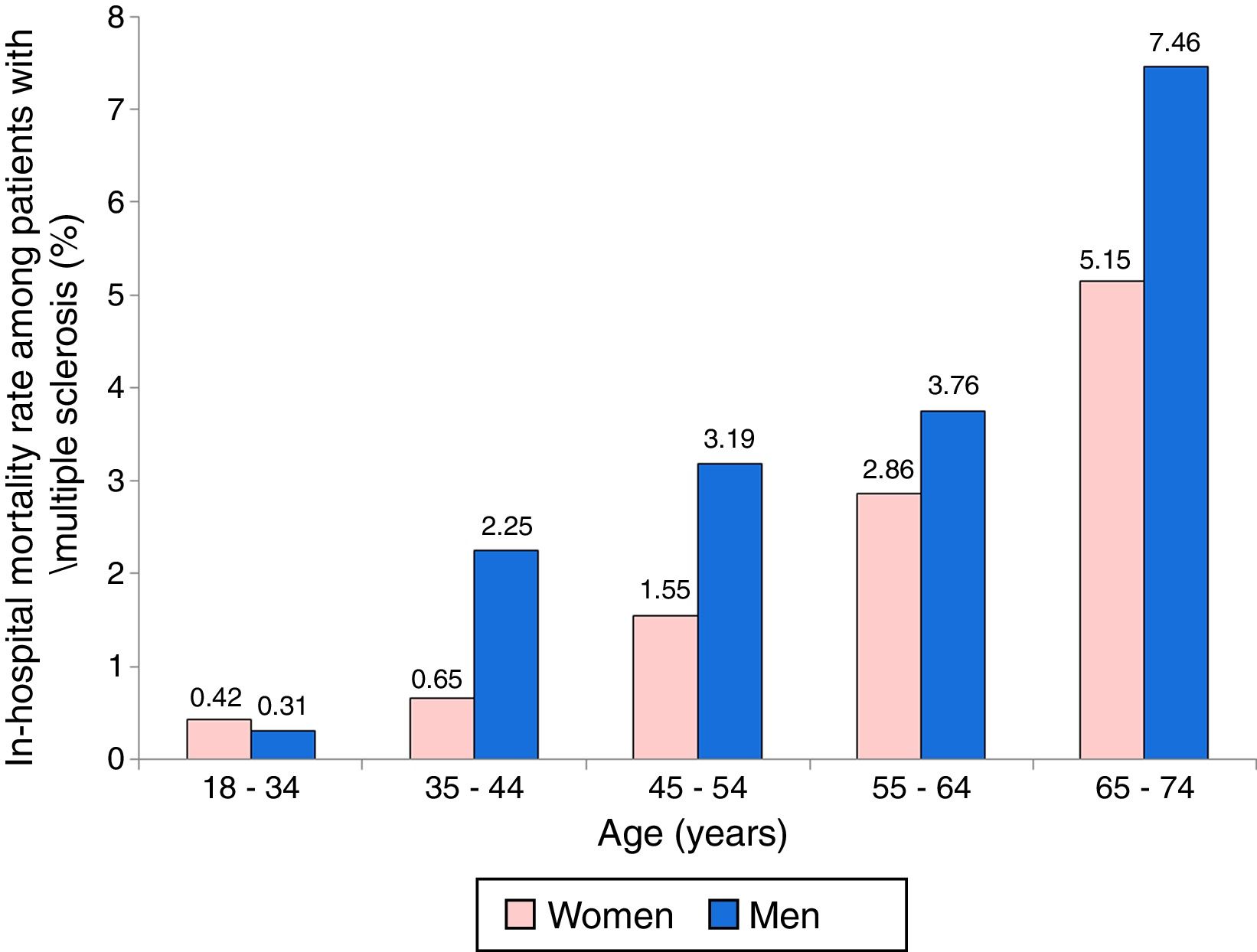

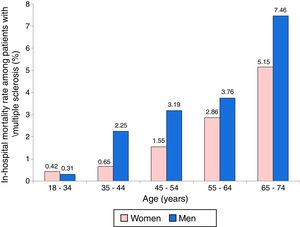

A total of 193 patients admitted due to MS died (99 women and 94 men). The raw mortality rate was 1.42% in women and 2.88% in men. Fig. 3 displays mortality rates by sex and age group; rates are higher among men and increase progressively with age.

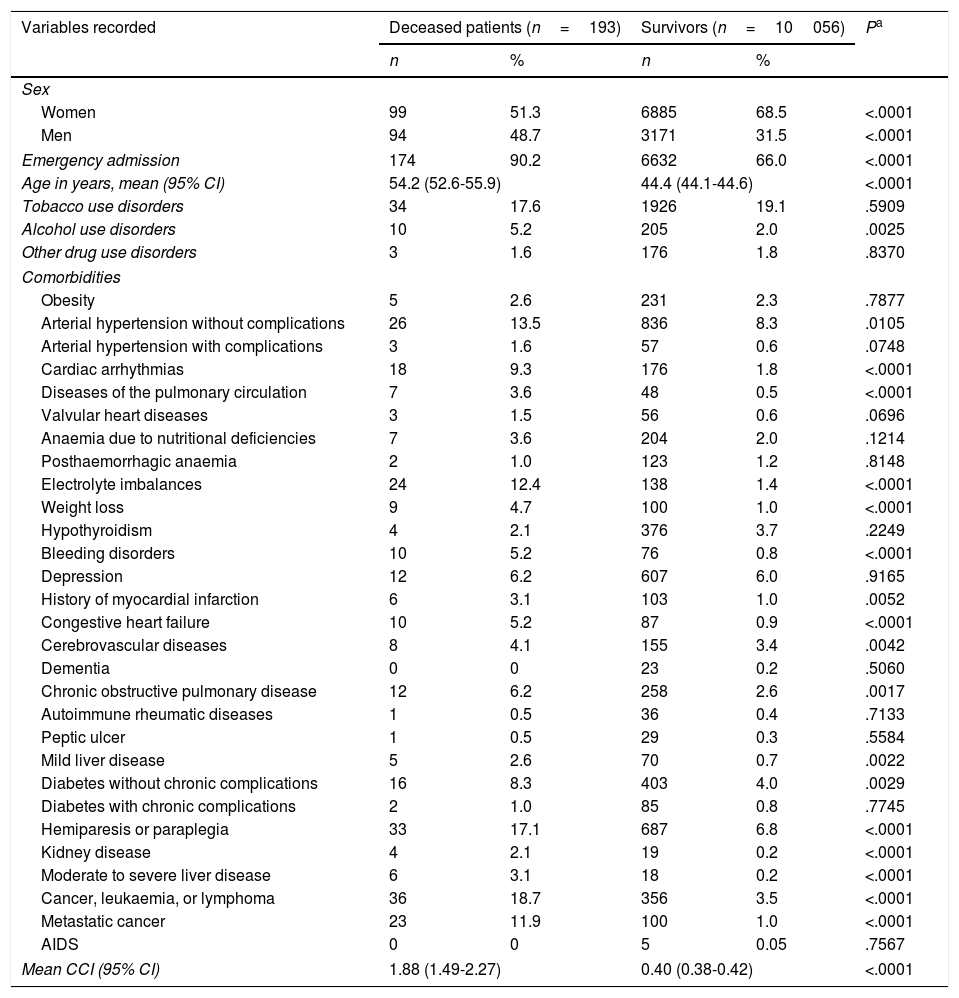

Table 3 compares the characteristics of patients who died during hospitalisation to those of survivors. Deceased patients were older (mean age, 54.2) and were more frequently admitted on an emergency basis (90.2%). The prevalence of AUDs was considerably higher among these patients than among survivors (5.2% vs 2.0%). They also showed a considerably higher CCI and were more likely to display certain comorbidities at admission, including arrhythmias, diseases of the pulmonary circulation, electrolyte imbalances, weight loss, bleeding disorders, congestive heart failure, liver damage, hemiparesis or paraplegia, kidney disease, cancer, leukaemia, lymphoma, and metastatic cancer.

Characteristics of deceased patients with MS and survivors.

| Variables recorded | Deceased patients (n=193) | Survivors (n=10056) | Pa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 99 | 51.3 | 6885 | 68.5 | <.0001 |

| Men | 94 | 48.7 | 3171 | 31.5 | <.0001 |

| Emergency admission | 174 | 90.2 | 6632 | 66.0 | <.0001 |

| Age in years, mean (95% CI) | 54.2 (52.6-55.9) | 44.4 (44.1-44.6) | <.0001 | ||

| Tobacco use disorders | 34 | 17.6 | 1926 | 19.1 | .5909 |

| Alcohol use disorders | 10 | 5.2 | 205 | 2.0 | .0025 |

| Other drug use disorders | 3 | 1.6 | 176 | 1.8 | .8370 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Obesity | 5 | 2.6 | 231 | 2.3 | .7877 |

| Arterial hypertension without complications | 26 | 13.5 | 836 | 8.3 | .0105 |

| Arterial hypertension with complications | 3 | 1.6 | 57 | 0.6 | .0748 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 18 | 9.3 | 176 | 1.8 | <.0001 |

| Diseases of the pulmonary circulation | 7 | 3.6 | 48 | 0.5 | <.0001 |

| Valvular heart diseases | 3 | 1.5 | 56 | 0.6 | .0696 |

| Anaemia due to nutritional deficiencies | 7 | 3.6 | 204 | 2.0 | .1214 |

| Posthaemorrhagic anaemia | 2 | 1.0 | 123 | 1.2 | .8148 |

| Electrolyte imbalances | 24 | 12.4 | 138 | 1.4 | <.0001 |

| Weight loss | 9 | 4.7 | 100 | 1.0 | <.0001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 4 | 2.1 | 376 | 3.7 | .2249 |

| Bleeding disorders | 10 | 5.2 | 76 | 0.8 | <.0001 |

| Depression | 12 | 6.2 | 607 | 6.0 | .9165 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 6 | 3.1 | 103 | 1.0 | .0052 |

| Congestive heart failure | 10 | 5.2 | 87 | 0.9 | <.0001 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 8 | 4.1 | 155 | 3.4 | .0042 |

| Dementia | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0.2 | .5060 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 12 | 6.2 | 258 | 2.6 | .0017 |

| Autoimmune rheumatic diseases | 1 | 0.5 | 36 | 0.4 | .7133 |

| Peptic ulcer | 1 | 0.5 | 29 | 0.3 | .5584 |

| Mild liver disease | 5 | 2.6 | 70 | 0.7 | .0022 |

| Diabetes without chronic complications | 16 | 8.3 | 403 | 4.0 | .0029 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 2 | 1.0 | 85 | 0.8 | .7745 |

| Hemiparesis or paraplegia | 33 | 17.1 | 687 | 6.8 | <.0001 |

| Kidney disease | 4 | 2.1 | 19 | 0.2 | <.0001 |

| Moderate to severe liver disease | 6 | 3.1 | 18 | 0.2 | <.0001 |

| Cancer, leukaemia, or lymphoma | 36 | 18.7 | 356 | 3.5 | <.0001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 23 | 11.9 | 100 | 1.0 | <.0001 |

| AIDS | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.05 | .7567 |

| Mean CCI (95% CI) | 1.88 (1.49-2.27) | 0.40 (0.38-0.42) | <.0001 | ||

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index.

A total of 174 patients of the 6806 admitted on an emergency basis died (2.6%), compared to only 19 of the 3424 scheduled admissions (0.06%); the risk ratio was 4.6 (95% CI, 2.9-7.4; P<.0001).

The most common main diagnoses among the 193 patients with MS who died during hospitalisation were disorders directly associated with MS (28% of patients), respiratory diseases (18.1%), infections (17.1%), neoplasia (16.1%), cardiovascular diseases (9.3%), digestive disorders (4.7%), and other diagnoses (6.7%)

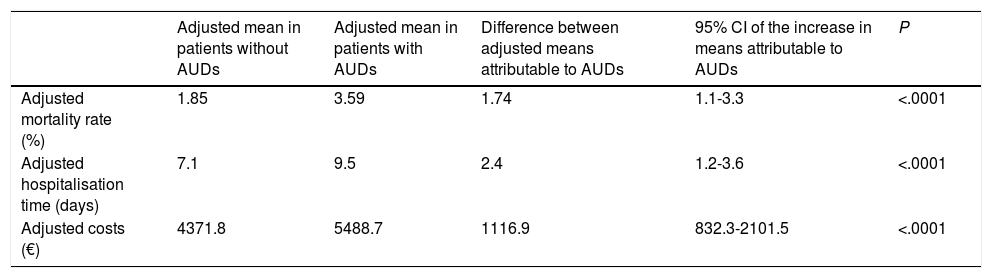

Associated mortality, extended hospital stays, and overexpenditureTable 4 shows the results of the MANCOVA, which included age, sex, hospital group, type of admission, all addictions, and CCI.

In-hospital mortality, extended hospital stays, and overexpenditure attributable to alcohol use disorders in patients with multiple sclerosis.a

| Adjusted mean in patients without AUDs | Adjusted mean in patients with AUDs | Difference between adjusted means attributable to AUDs | 95% CI of the increase in means attributable to AUDs | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted mortality rate (%) | 1.85 | 3.59 | 1.74 | 1.1-3.3 | <.0001 |

| Adjusted hospitalisation time (days) | 7.1 | 9.5 | 2.4 | 1.2-3.6 | <.0001 |

| Adjusted costs (€) | 4371.8 | 5488.7 | 1116.9 | 832.3-2101.5 | <.0001 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AUD: alcohol use disorder.

The adjusted mortality rate in the multivariate model was significantly higher among patients with MS and AUDs (3.59% vs 1.85% in patients with no AUDs), with a difference between means of 1.74%; this represents a 94.1% increase in mortality attributable to AUDs.

The mean hospital stay was also significantly longer in patients with AUDs (9.5 vs 7.1 days), with a mean increase in hospitalisation time of 2.4 days attributable to AUDs.

Mean hospitalisation costs were also significantly higher among patients with AUDs (€5488.70 vs €4371.80), with an overexpenditure of €1116.90 per case.

DiscussionOur results suggest that AUDs have a considerable impact on in-hospital mortality in patients with MS and result in significantly longer hospital stays and higher expenses. Both isolated episodes of excessive alcohol consumption and chronic alcohol use disorders have an impact on the course of the disease and result in severe complications.

Some of the most frequent causes of death in these patients were diseases frequently associated with AUDs, such as pneumonia and other respiratory tract infections,31 sepsis,32 urinary tract infections, and other types of infections, which are closely linked to immunosuppression associated with AUDs.33 According to the literature, patients with MS are 3.7 times more likely to experience pneumococcal pneumonia than the general population34; the incidence of urinary and respiratory tract infections, gastrointestinal infections, and other types of infections increases the risk of MS relapses.35,36

Given the large sample size and the wide range of hospitals represented in our study, our results may be extrapolated to other populations. To our knowledge, this is the first Spanish study analysing increased mortality, extended hospital stays, and overexpenditure attributable to AUDs in patients with MS.

Adequately controlling for confounding is the main challenge of studies analysing the impact of AUDs on prognosis and other outcome measures in hospitalised patients. Hospital stays, costs, and in-hospital mortality vary depending on a number of causes, including reason for admission, disease severity, comorbidities, type of hospital, and other patient social and demographic characteristics.37 Inclusion of the hospital group in the multivariate model to control for the confounding effect is extremely important: previous research suggests that centre type, available equipment, and care standards have an impact on quality of care.31

Our study has a number of limitations. We used only data from the MBDS and did not include complementary patient data. We also used the definitions of addictions, MS, and comorbidities used by physicians at each centre; these were subsequently coded and recorded into the database by specialised staff who were not aware of inter-centre variability. The ICD-9 code for MS is used internationally in studies using databases of hospital discharges, but does not enable comparison of these diagnoses with clinical, imaging, and laboratory findings from patients’ clinical histories. Previous studies have reported a high sensitivity and specificity of ICD-9 code 340 in hospitalised patients with MS26 when all diagnostic codes (not only the main diagnosis) are included; on many occasions, patients with MS are admitted with complications or other diagnoses that are recorded as the main diagnosis, leaving MS as a secondary diagnosis. To avoid this information bias, we considered all diagnostic codes and not only the main diagnosis. Another limitation of our study is that the MBDS does not include data on patient disability (for example, Expanded Disability Status Scale scores), which prevents us from assessing the impact of the level of disability on mortality, hospital stays, and hospitalisation costs.

Using these databases also has considerable advantages. The data included are usually entered after discharge; as all cases are registered, they provide fairly accurate information on the incidence, prevalence, comorbidities, complications, and mortality of the diseases attended in hospitals.37,38 These data may be analysed retrospectively, unlike in studies with other designs requiring prospective data collection. The collection of data from large samples and for long periods, as in the present study, can be relatively fast and easy; as data are gathered systematically, costs are considerably lower. The risk of selection bias in these studies is lower since patients (or their legal representatives) cannot refuse to participate in the study. The availability of data about costs for each DRG, stratified by hospital group and year, is another significant advantage, as this makes it easier to calculate overexpenditure due to MS and AUDs.

A consensus document drafted by several Spanish scientific societies recommends pneumococcal vaccination of adults with underlying diseases, including AUDs39; this recommendation should be followed at all healthcare levels, including hospital services identifying patients with AUDs. The impact of AUDs on mortality, hospital stay duration, and overexpenditure associated with pneumococcal pneumonia in Spain supports this recommendation.40 Recent review articles recommend vaccination not only against pneumococcal infection but also against meningococcal and Haemophilus influenzae infection in patients with MS, mainly among those receiving immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapy.34,41

Diagnosing and beginning to treat alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use disorders should be one of the main therapeutic goals before discharging a patient with MS. Enquiring into alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use is essential from an ethical and from a professional viewpoint. Several studies have shown the effectiveness of a brief intervention on alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use, and informing the primary care physician about the problem in the discharge report42–44; this approach may prevent complications and hospital readmissions. Reducing the number of admissions and readmissions attributable to these disorders would help reduce the costs associated with patients’ absence from work and hospital stays, increasing hospital bed availability and considerably decreasing the risk of mortality.

ConclusionsAmong hospitalised patients with MS, AUDs increase in-hospital mortality rate by 94.1%, extend hospital stays an additional 2.4 days, and result in an overexpenditure of €1116.90. Such preventive measures as controlling alcohol use and administering specific vaccinations may contribute to reducing the magnitude of the problem in these patients.

FundingThis study was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality as part of the national drugs plan (grant 2009I017, project G41825811), and by the Andalusian Regional Department of Health and Social Affairs funding for biomedical and health science research in 2013 (PI-0271-2013).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gili-Miner M, López-Méndez J, Vilches-Arenas A, Ramírez-Ramírez G, Franco-Fernández D, Sala-Turrens J, et al. Esclerosis múltiple y trastornos asociados al consumo de alcohol: mortalidad atribuible, prolongación de estancias y exceso de costes hospitalarios. Neurología. 2018;33:351–359.