Cryptococcal meningitis is a globally distributed, subacute, opportunistic infection spread by aerosolised spores, and usually affects immunosuppressed individuals.1,2 Two causal pathogens exist, Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii.3 Neurological symptoms are the most common non-pulmonary form of presentation.4 Diagnosis is based on cerebrospinal fluid findings of pleocytosis, elevated protein levels, and low glucose levels; positive results from cryptococcal antigen testing and conventional culture are definitive.1,4–6 The mortality rate associated with the disease exceeds 20%.7 One rare complication is ischaemic stroke manifesting as multiple vascular lesions, which negatively affects prognosis.8

We present a relevant case in which the diagnosis was reached due to presentation of stroke with atypical neuroimaging findings.

The patient was a 62-year-old man with history of occupational pulmonary fibrosis due to flour dust inhalation, arterial hypertension, osteoporosis, and hypergammaglobulinaemia following prolonged corticotherapy. The patient underwent single lung transplantation with triple immunosuppressive therapy (tacrolimus, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate). Three months after transplantation, the patient was admitted to the neurology department due to subacute onset of dysarthria, headache, and tremor, which were attributed to moderate hyponatraemia (128mEq/L) and calcineurin inhibitor neurotoxicity. No lesions were detected in a brain MRI study. The patient’s symptoms improved and he was discharged.

A month later, he consulted the emergency department due to asthenia, headache, incoherent speech, dysarthria, and instability. A head CT scan identified no acute lesions. Once more, the patient presented hyponatraemia, which was slowly corrected during hospitalisation. An EEG study showed diffuse slowing of theta activity. Despite correction of ion levels and switching the immunosuppressive treatment, the patient did not improve, and he presented fever 2 weeks later. Serology findings and PCR results for SARS-CoV-2 were negative. The blood culture revealed yeast-like fungi, and treatment was started with fluconazole and amphotericin B.

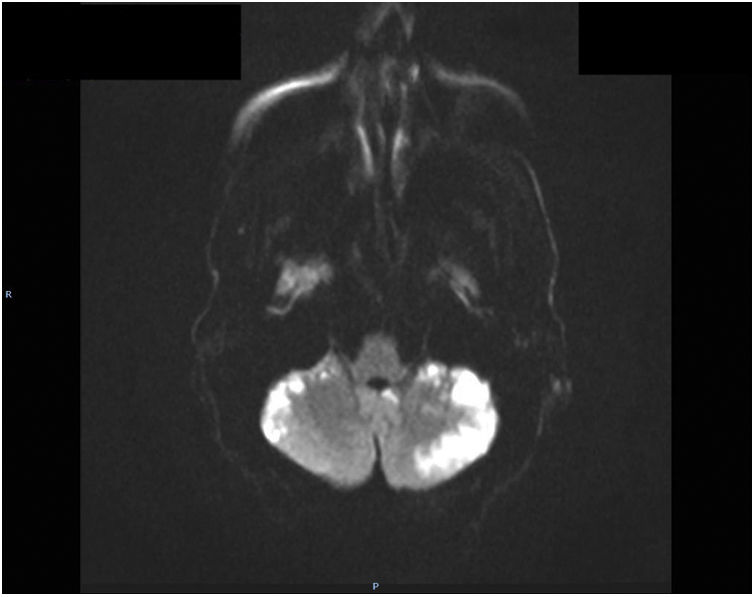

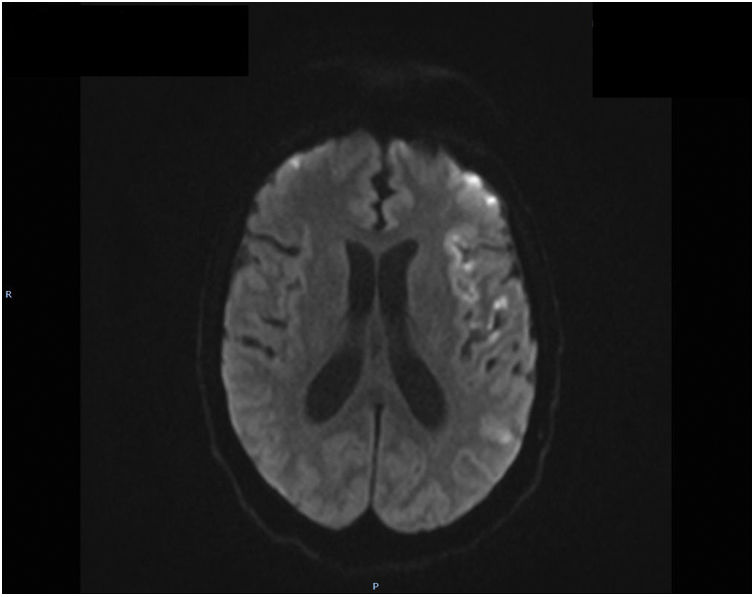

The patient presented sudden onset of focal neurological signs with facial palsy, dysarthria, and right hemiparesis, and code stroke was activated. A head CT scan revealed no evidence of acute ischaemia, the CT perfusion study showed no asymmetries suggestive of ischaemia, and the CT angiography study did not detect vessel stenosis. Symptoms regressed; therefore, the patient was not eligible for intravenous thrombolysis. A cardiac ultrasound performed as part of the aetiological study identified no structural anomalies. Holter ECG monitoring detected no arrhythmia. Brain MRI (Figs. 1 and 2) revealed numerous cortical hyperintensities on T2/FLAIR sequences, and particularly on diffusion sequences. Lesions involved both hemispheres (but predominantly the left), and were very marked in the cerebellar hemispheres, and were consistent with acute infarcts not corresponding to a particular vascular territory. Lumbar puncture revealed an opening pressure of 30cm H2O; CSF analysis revealed lymphocytic pleocytosis (22cells/mm3), low glucose level, and high protein level (117mg/dL). Gram staining revealed yeast-like fungi. Antigen testing identified C. neoformans. Despite antifungal therapy, the patient died a week later.

Cryptococcosis is the third most common infection in patients undergoing transplantation, with mortality rates reaching 50% if it is associated with meningoencephalitis.5,9,10 The mean time from lung transplantation to symptom onset is 191 days, with C. neoformans being the most common cause of infection.5,11 In our patient, onset of the first symptoms was earlier than usual, 90-120 days after transplantation. Symptoms are secondary to intracranial hypertension. A rare complication of this disease is ischaemic stroke, usually with multiple lacunar infarcts. The pathogenic mechanism is obliterating endarteritis secondary to possible infectious vasculitis.8 Curiously, our patient presented cortical in addition to lacunar infarcts, predominantly affecting the posterior fossa and cerebellum, consistent with neuroimaging12 findings of multiple vasculopathy. We suspected fungal infection in the context of immunosuppression,13 complicated by meningoencephalitis and cerebral vasculitis, although due to the patient’s early death we were unable to perform a brain angiography study, the gold standard diagnostic test. The lumbar puncture revealed intracranial hypertension,14 and our hypothesis was confirmed by the antigen test. It should be noted that in HIV-positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy, any previous infection may be concealed by immune reconstitution syndrome.1

Treatment for cryptococcal meningitis in transplant patients begins with a 2-week induction phase with amphotericin B and flucytosine. In the consolidation and maintenance phase, patients receive fluconazole (400-800mg daily for 8 weeks; then 200-400mg daily for 12 months).5 We were unable to complete the induction phase in our patient due to his early death.

In conclusion, cryptococcosis should be strongly suspected in at-risk patients presenting progressive neurological symptoms. It is important to establish diagnosis and treatment early with a view to preventing such severe complications as multiple cerebral ischaemia or intracranial hypertension, which modify the course of the disease and are associated with potentially fatal outcomes.15

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Please cite this article as: Peláez N, Dunlop D, Negro E. Infarto cerebral múltiple como complicación de meningitis criptocócica en paciente con trasplante unipulmonar. Neurología. 2022;37:411–412.