Oral anticoagulation (OAC) use increases the risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2. Left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) is an alternative to OAC, however data about its use in patients with prior ICH is scarce and the timing of its performance is controversial. Furthermore, the long-term outcomes in this group of patients have not been described previously.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the safety and efficacy of LAAO in patients with non-valvular AF and prior ICH (CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2) and to determine adequate timing of its performance.

MethodsThis is a multicenter retrospective registry that included 128 patients, whose indication for this procedure was ICH. Patients were divided into two groups: early occlusion (n=31; 24.2%), in which the procedure was performed before 90 days had elapsed after the bleeding, and late occlusion (n=97; 75.8%), after 90 days.

ResultsGlobal procedural success was of 97% (124/128). Procedure-related complications occurred in 4 patients (3.15%): 2 cardiac tamponade, 1 device embolization and 1 transient ischemic attack during hospitalization. There was a significant reduction in the ischemic and bleeding rates compared to expected based on CHA2DS2-VASc and HASBLED scores (93.9% and 89.9% respectively) after a mean follow-up of 73.9±34.1 months. There were no significant differences neither in baseline characteristics between the early and late occlusion groups nor in the procedural success or complications rates. Furthermore, no statistically significant differences were found in mortality, ischemic events, or hemorrhage between the early and late occlusion group.

ConclusionsLeft atrial appendage occlusion is an effective and safe treatment alternative to reduce the risk of ischemic stroke in selected patients with atrial fibrillation and prior intracranial hemorrhage. In this study, we did not find differences regarding safety and efficacy in early closure compared with late closure. Further studies are needed to support early closure to reduce the complications associated with oral anticoagulation withdrawal.

El uso de anticoagulantes orales conlleva un aumento del riesgo de hemorragias intracraneales en pacientes con fibrilación auricular y CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2. El cierre percutáneo de orejuela izquierda sería una alternativa a la anticoagulación oral, aunque la evidencia en relación a los pacientes con sangrados cerebrales es todavía escasa y el momento idóneo de realizar el mismo, controvertido. Además de todo ello, hasta el momento el seguimiento a largo plazo descrito en este perfil de pacientes no ha sido analizado.

ObjetivosEvaluar la eficacia y seguridad del cierre percutáneo de orejuela izquierda en pacientes con fibrilación auricular y hemorragia intracranial y determinar el momento adecuado para realizar el procedimiento.

MétodosRegistro multicéntrico que incluyó 403 pacientes con fibrilación auricular y cierre percutáneo de orejuela izquierda. En 128 (31,8%) de ellos, la indicación fue hemorragia intracraneal. Estos pacientes fueron divididos en dos grupos: cierre precoz (n=31; 24,2%), en los cuales el cierre se realizó en los primeros 90 días tras el sangrado cerebral, y cierre tardío (n=97; 75,8%), tras más de 90 días.

ResultadosEl éxito global del procedimiento fue del 97% (124/128). Complicaciones relacionadas con la intervención ocurrieron en 4 pacientes (3.15%): 2 taponamientos cardiacos, 1 embolización de dispositivo y 1 accidente isquémico transitorio. Se evidenció una reducción significativa en cuanto a los eventos isquémicos y sangrados respecto a los estimados por las escalas de riesgo CHA2DS2-VASc y HASBLED (93.9% y 89.9% respectivamente) tras una media de seguimiento de 73.9±34.1 meses. No existían diferencias significativas en las características basales de ambos grupos (precoz y tardío) y tampoco se objetivaron en cuanto a las complicaciones o éxito del procedimiento. Además, no se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en mortalidad, eventos isquémicos o sangrados entre grupos.

ConclusionesEl cierre percutáneo de orejuela izquierda es una alternativa segura y eficaz para reducer el riesgo isquémico y de sangrado en pacientes con fibrilación auricular y antecedente de hemorragia intracranial. En este estudio no se encontraron diferencias en cuanto a la eficacia o seguridad entre los grupos de cierre precoz o tardío. Nuevas investigaciones serán necesarias para soportar la teoría de que el cierre precoz reducirá las complicaciones asociadas a la anticoagulación en este perfil de pacientes.

Oral anticoagulation (OAC) is the standard of care for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation and high embolic risk (CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2). One of the most concerning complications of OAC is intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), which occurs in 3–6% of the patients, increasing their risk ten-fold compared to the general population.1,2 The use of OAC has been reported in 20% of ICH approximately and ICH is responsible for 9–27% of all strokes worldwide. Total death rate at 1 month is 40%, increasing to 54% at one year.3–5 Due to the poor outcome and so few effective interventions, the optimal management of patients with ICH is a priority.

After an intracranial bleeding, the risk of both hemorrhagic and ischemic cerebral events is increased.6 In patients receiving OAC, early reintroduction of treatment may lead to a new bleeding episode, while its delay is associated with an increased risk of an ischemic event. Percutaneous occlusion of the left atrial appendage, which eliminates the need for long-term OAC, has become a therapeutic alternative recommended in some guidelines and consensus papers.7,8 However, the optimal timing for the performance of the procedure remains controversial. Early occlusion after the bleeding might provide protection against ischemic events, but the use of intraprocedural anticoagulation might also imply an increased risk of a recurrent hemorrhage.9,10

The aims of this study are to evaluate the safety and efficacy of left atrium appendage occlusion in patients with non-valvular AF and prior ICH in a multicenter registry, and to compare the outcomes of early occlusion versus late occlusion.

MethodsPopulationThis a retrospective study that included 128 patients in which left appendage occlusion was performed after an episode of ICH at seven centers in Spain and Canada. As this is an exploratory analysis, no formal sample size calculation was performed.

All patients underwent standard diagnostic evaluation including routine medical history, physical examination, and electrocardiography and laboratory testing, as well as transthoracic echocardiography. Estimation of thromboembolic and bleeding risk was based on CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores.

Clinical, imaging, and procedural characteristics, as well as antithrombotic regimen and post-procedural outcomes, were registered in a dedicated electronic database by each of the participating centers.

The study protocol complied with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the local ethics committee at each of the clinical sites. All subjects provided informed consent before the procedure.

Study designPatients were divided into two groups: early occlusion, in which the procedure was performed before 90 days had elapsed after the bleeding, and late occlusion, after 90 days. A period of 90 days was chosen because of the higher mortality associated with OAC underuse described during the first 90 days after an ICH. Thirty-one patients were included in the first group (24.2%) and 97 in the latter (75.8%).

Procedural characteristics and outcomesProcedures were performed under general anesthesia or local analgesia, according to local practice. Likewise, procedural imaging guidance with TEE, micro-TEE, or intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) was selected at the implanting physician′s discretion.

Peri-procedural complications included cardiac perforation, pericardial effusion and tamponade, hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, device thrombosis, embolization, access-related complications, and bleeding. Bleeding events were classified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) definition. Major bleedings were considered type ≥3 of BARC.

Post-procedural clinical and imaging follow-up was performed as per usual care in each participating center. Post-procedural antithrombotic treatment was tailored to the patient's individual bleeding and ischemic risk. During follow-up, adverse events were registered, including death, neurological and hemorrhagic events, pericardial effusion, tamponade, and late device-related complications.

Peridevice leaks were defined according to the color Doppler jet width and classified as significant if ≥5mm by either TEE or CT.11,12 Peri-procedural device dislodgment and embolization, and late device embolization during follow-up were also recorded.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are represented by mean and standard deviation or median and quartiles and categorical variables by frequencies and percentages. T-test was used to compare continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. Cumulative incidence for the composite endpoint was determined using the Kaplan–Meier method, with the date of the LAAO as initial time of follow-up. Survival analyses were performed with the use of log-rank test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Patients missing follow-up were considered at risk until the date of last contact follow-up, at which point they were censored. The analysis was performed with SPSS 26.0 and R Software 7 Ed.

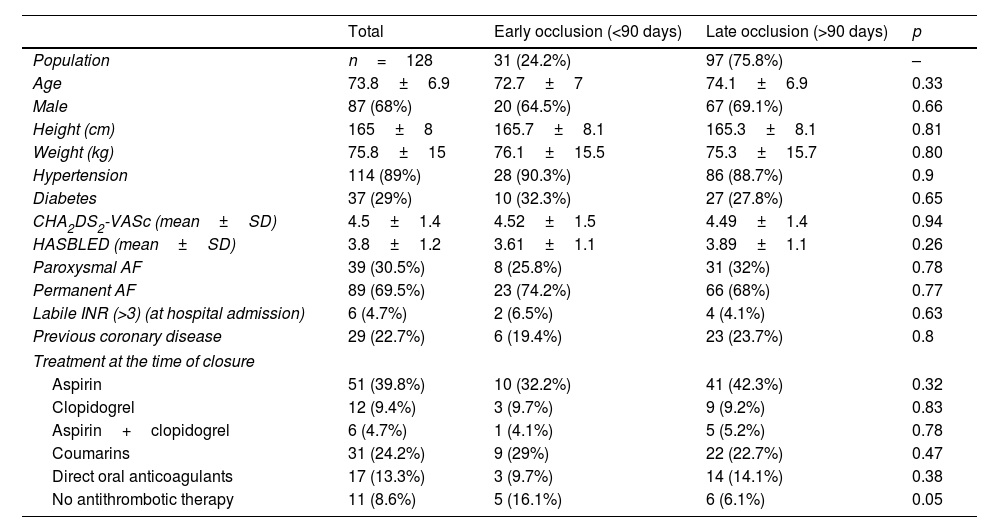

ResultsBaseline characteristicsOne hundred twenty-eight patients with previous intracranial hemorrhage and indication for oral anticoagulation (non-valvular AF and CHA2DSVASc ≥2) were identified. Mean age was 73.8±6.9 years old and 68% were male. Baseline clinical characteristics of the global population and of both groups are shown in Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the sample and of both groups.

| Total | Early occlusion (<90 days) | Late occlusion (>90 days) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | n=128 | 31 (24.2%) | 97 (75.8%) | – |

| Age | 73.8±6.9 | 72.7±7 | 74.1±6.9 | 0.33 |

| Male | 87 (68%) | 20 (64.5%) | 67 (69.1%) | 0.66 |

| Height (cm) | 165±8 | 165.7±8.1 | 165.3±8.1 | 0.81 |

| Weight (kg) | 75.8±15 | 76.1±15.5 | 75.3±15.7 | 0.80 |

| Hypertension | 114 (89%) | 28 (90.3%) | 86 (88.7%) | 0.9 |

| Diabetes | 37 (29%) | 10 (32.3%) | 27 (27.8%) | 0.65 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc (mean±SD) | 4.5±1.4 | 4.52±1.5 | 4.49±1.4 | 0.94 |

| HASBLED (mean±SD) | 3.8±1.2 | 3.61±1.1 | 3.89±1.1 | 0.26 |

| Paroxysmal AF | 39 (30.5%) | 8 (25.8%) | 31 (32%) | 0.78 |

| Permanent AF | 89 (69.5%) | 23 (74.2%) | 66 (68%) | 0.77 |

| Labile INR (>3) (at hospital admission) | 6 (4.7%) | 2 (6.5%) | 4 (4.1%) | 0.63 |

| Previous coronary disease | 29 (22.7%) | 6 (19.4%) | 23 (23.7%) | 0.8 |

| Treatment at the time of closure | ||||

| Aspirin | 51 (39.8%) | 10 (32.2%) | 41 (42.3%) | 0.32 |

| Clopidogrel | 12 (9.4%) | 3 (9.7%) | 9 (9.2%) | 0.83 |

| Aspirin+clopidogrel | 6 (4.7%) | 1 (4.1%) | 5 (5.2%) | 0.78 |

| Coumarins | 31 (24.2%) | 9 (29%) | 22 (22.7%) | 0.47 |

| Direct oral anticoagulants | 17 (13.3%) | 3 (9.7%) | 14 (14.1%) | 0.38 |

| No antithrombotic therapy | 11 (8.6%) | 5 (16.1%) | 6 (6.1%) | 0.05 |

In 97 patients (75.8%), late left appendage occlusion (after 90 days) was performed, while early occlusion (before 90 days) was performed in 31 patients (24.2%). CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED were similar between both groups, (4.5±1.5; 3.6±1.1 in the early closure group and 4.5±1.4; 3.9±1.1 in the late closure group), underscoring the high hemorrhagic risk of the population of study. There were no differences in the rest of the baseline characteristics or preprocedural anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy (Table 1).

OutcomesIntraprocedural and in-hospital outcomes in both groups are summarized in Table 2. Procedural success was of 97% (124/128). In 85.5% of the patients Amplazter Cardiac Plug or Amulet device (Abbot vascular) were used. Peri-procedural complications occurred in 3 patients (3.15%), encompassing 2 cardiac tamponade (0.6%) requiring percutaneous drainage and 1 device embolization. Intraprocedural death, need of emergent surgery or stroke were not described in any of the groups of study.

Procedural characteristics and in-hospital complications.

| Total | Early occlusion <90 days) | Late occlusion (>90 days) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural success (%) | 124/128 (97%) | 30/31 (96.77%) | 94/97 (96.9%) | 0.28 |

| Procedure time (min) | 80±41 | 78±19.6 | 81±42 | 0.68 |

| Contrast (ml) | 148.2±68.2 | 153.2±65.3 | 147.1±68.2 | 0.79 |

| Procedural tamponade | 2 (1.6%) | 0 | 2 (2.1%) | 0.6 |

| Complete occlusion | 124 (97%) | 30 (97%) | 94 (96.9%) | 0.64 |

| Procedural stroke (TIA) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0.31 |

| In-hospital mortality | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 0.43 |

| In-hospital stroke | 1 (0.8%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0.83 |

| Pericardial effusion(severe/tamponade) | 4 (3.2%) | 0 | 4 (4.2%)3 percutaneous drainage1 surgery | 0.73 |

| In-hospital bleeding | Minor: 1 (0.8%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0.31 |

| Major: 3 (2.3%) | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (1%) | 0.16 |

In-hospital mortality was of 1.5%, with two fatal events not related to the intervention (respiratory infection and neurological sequelae of the intracranial hemorrhage). The most frequent in-hospital complication was femoral hematoma, which occurred in three patients. One single patient of the late group suffered an episode of brain hemorrhage during hospitalization.

Follow-upMean follow-up was of 73.9±34.1 months. A follow-up imaging technique (either CT or transesophageal echocardiogram) was performed at 3–6 months in 89.1%. Four device thrombosis were found, all of which occurred in the late occlusion group. Adjuvant antiplatelet therapy was dual antiplatelet therapy in three patients and treatment with clopidogrel alone in one patient. Ten peridevice shunts were observed, all of them inferior to 5mm. There were no significant differences in the adjuvant therapy at last follow-up (Table 3). Early dual antiplatelet therapy followed by monotherapy with ASA after the first echocardiographic control was the preferred antithrombotic therapy in both groups (54.8% of patients in the early group compared with 61.9% in the late group; p=0.57).

Follow-up and complications.

| Total | Early occlusion(< 90 days) | Late occlusion(> 90 days) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up time (months) | 73.9±34.1 | 71.8±24.4 | 74.1±34.8 |

| Follow-up treatment | |||

| Aspirin | 77 (60.2%) | 17 (54.8%) | 60 (61.9%) |

| Clopidogrel | 22 (17.2%) | 6 (19.4%) | 16 (16.5%) |

| DAPT | 19 (14.8%) | 6 (19.4%) | 13 (13.4%) |

| Anticoagulation | 10 (7.8%) | 2 (6.6%) | 8 (8.2%) |

| Follow-up TEE | 93 (72.6%) | 21 (67.7%) | 72 (74.2%) |

| Follow-up thrombus (TEE 45 days) | 4 (3.1%) | 0 | 4 (4.1%) |

| Follow-up shunt | 10 (7.8%) | 3 (9.7%) | 7 (7.2%) |

| Overall mortality | 34 (26.6%; 4.4% per year) | 5 (16.1%; 2.5% per year) | 29 (29.8%; 5% per year) |

| Follow-up stroke | 8 (6.3%; 1% per year) | 3 (9.7%; 1.5% per year) | 5 (5.2%; 0.9% per year) |

| Ischemic stroke | 3 (2.3%; 0.4% per year) | 2 (6.5%; 1% per year) | 1 (1%; 0.2% per year) |

| Follow-up TIA | 2 (1.6%; 0.3% per year) | 1 (3.2%; 0.5% per year) | 1 (1%; 0.2% per year) |

| Intracranial bleeding | 5 (2.1%; 0.6% per year) | 1 (3.2%; 0.5% per year) | 4 (4.1%; 0.7% per year) |

All-cause mortality during follow-up was of 26.6% (34 patients) for the global group, with a 17.6% in the early group and 29.8% in the late occlusion group [log rank 0.3/Breslow 0.34; HR 0.47 (95% CI: 0.18–1.58; p=0.25)] (Fig. 1). Eight cerebrovascular events were registered (1% per year): three (1.5% per year) in the early group and five (0.9% per year) in the late occlusion group (p=0.36). Three of them were ischemic events (0.4% per year) and five were hemorrhagic (0.6% per year) (Table 3). Of the patients who suffered another ICH, four were under treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy and one with single antiplatelet therapy with ASA. Furthermore, two patients suffered a transient ischemic attack (TIA), one in each group.

There was an absolute and relative risk reduction of ischemic events in the global group of 6% and 93.9%, respectively, compared with the expected by the CHA2DS2-VASc score (Fig. 2). Regarding major bleeding episodes, incidence was of 0.8% per year, with an ARR and RRR of 6.9% and 89.9% compared with the predicted HAS-BLED. There were no differences between the early and late occlusion groups.

DiscussionThis multicenter registry of real clinical practice is, to the best of our knowledge, one of the largest reported series of patients with ICH, NVAF and LAAO13–16 and the one with the longest follow-up. in our study, LAAO in patients with prior ICH was associated with a low risk of ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic events during follow-up. Furthermore, ischemic and hemorrhagic events were also low in patients in which the procedure was performed in the first 90 days after the intracranial bleeding.

ICH is a frequent and severe type of stroke, accounting for 10–15% of all strokes, and global incidence rates are expected to increase in an ageing population. It is associated with high mortality rates (∼50%) and functional dependency in many survivors (∼2/3 of patients). ICH occurs in 3–6% of the patients treated with OAC, increasing their risk ten-fold compared to the general population.17,18 Furthermore, OAC and prior ICH are known to increase the risk of recurrent intracerebral bleeding. It has been estimated that 15% of patients who suffered ICH were already using OAC, and another 15% have a de-novo AF diagnosis, implying future OAC prescription.19

Up to date, no randomized clinical trials have addressed whether OAC should be resumed in ICH survivors, and the timing of its reintroduction. Therefore, this difficult decision should be based on patient's individual risk for ischemic complications versus hemorrhagic complications, particularly recurrent ICH. Registries show that the risk of new ICH is increased to 6% after resumption OAC. In the event of a new episode of ICH, patients who continue treatment with coumarins have a 50% increase in bleeding volume and three times more mortality compared with patients who were not under anticoagulant therapy.20–22 Even poorer results were obtained with double antiplatelet therapy compared with OAC in patients with AF, as it increased embolic risk without reducing bleeding events. Similar results have been observed with early therapies or bridging strategies with low molecular weight heparin. Given this risk, current recommendations focus on the need for individualized decision-making and careful risk–benefit evaluation.

Additionally, at least 8.1% of patients suffer an ischemic stroke after an ICH, and their mortality is increased 5.5 times compared with patients without previous ICH, particularly during the first 90 days after the bleeding episode. This increased risk of ischemic events after the bleeding episode is partly explained because anticoagulation is frequently withdrawn for a variable period of time, since evidence regarding OAC resumption and its optimal timing is scarce. Indeed, the time during which these patients do not receive OAC after the bleeding shows great variability in the literature, ranging from 2 to 30 weeks.23–26 However, obtaining significant results in this context might be hindered due to the severity of this clinical picture, its high mortality rates and the frequency of comorbidities that these patients present associated.

LAAO has become an established management option in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation at high risk of thromboembolic and bleeding complications. Consequently, LAAO has emerged as an attractive alternative to OAC in NVAF patients with prior ICH. However, data are scarce, as these patients had been excluded from the larger registries and pivotal studies. Furthermore, timing for LAAO after ICH is extremely variable in different registries, ranging from less than 3 months to 30±48 months.

In our study, we report a success and complication rates similar to previous reports in patients with LAAO and ICH, without significant differences between early and late LAAO. Although this is an observational study, and the results should be considered as an exploratory analysis, early LAAO should be considered as a therapeutic alternative in selected patients with ICH. Indeed, the risk of stroke (either ischemic or hemorrhagic) after an ICH is increased three-fold, particularly during the first weeks. Therefore, it is of vital importance to guarantee early prevention of ischemic events, without a significant increase in hemorrhagic risk. As early resumption of oral anticoagulation might pose a higher risk of recurrent ICH, in many of these patients treatment is discontinued. In our registry, early LAAO was not associated with significant intraprocedural or in-hospital complications, suggesting it is safe to perform the procedure in these patients. Furthermore, in this study, early LAAO was associated with a lower incidence of ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic events during follow-up, compared with the expected incidence by CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scales.

There were no statistically significant differences in mortality during follow-up between both groups. However, deaths during follow-up were numerically higher in the late closure group, which may reflect lack of statistical power to detect differences in mortality with this sample size. In spite of this, it should be noted that due to the characteristics of this study, part of this difference might be explained by selection bias, and that other clinical characteristics of patients that were not taken into account.

Based on these results, early LAAO might be considered an alternative to OAC for early stroke prevention in patients who have suffered ICH. However, ongoing clinical trials will clarify which strategy (OAC resumption, LAAO or no antithrombotic therapy) is the preferred alternative for secondary stroke prevention in ICH survivors with atrial fibrillation.27–29

LimitationsThe results of this study are based on a non-randomized, retrospective, observational study in which data were collected through a dedicated electronic database at multiple clinical sites. Information was registered by trained cardiologists, involved in the procedure. However, we lacked a central core lab to assess imaging and procedural data and event adjudication was not crosschecked. Moreover, routine follow-up imaging was not available in 13 patients (10.9%). In the majority of cases, this was due to performance of follow-up diagnostic techniques at the referring center, which did not always report results back to the hospital performing the procedure. Other reasons for lack of follow-up imaging included patient's preference or worsening renal function that precluded CT examination in patients unsuitable to undergo TEE.

In addition, the main limitation of this study is the non-randomized design of the study and lack of a control group constitute a further limitation, and the possibility of patient selection bias cannot be discarded. Only patients in which the procedure was performed were included in the registry, instead of all eligible patients. Theoretically, some patients with indication for LAAO after an ICH the procedure might not have been eventually performed because of occurrence of an event (death, severe bleeding or ischemic event). This scenario could be potentially more frequent in the late occlusion group, as the period at risk of bleeding (because of reintroduction of OAC) or ischemic complications (due to inappropriate anticoagulation after the hemorrhagic episode) would be longer.

ConclusionsLeft atrial appendage occlusion is an effective and safe treatment option to reduce the risk of ischemic stroke in selected patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients and prior intracranial hemorrhage. In this study, we did not find differences in safety and efficacy between early closure and late closure. Further studies are needed to support early closure to reduce the complications associated with oral anticoagulation withdrawal.

Left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) is an attractive alternative to oral anticoagulation in patients who have suffered an intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), although in this context, data are scarce and timing for LAAO has not been established.

What is new?Early LAAO in patients with ICH is safe and effective, reducing ischemic and hemorrhagic events compared with the expected incidence by CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scales.

Dr. Cruz-Gonzalez is proctor for Abbott and Boston Scientific. Dr. Nombela-Franco is proctor for Abbott.

Dr Cruz-Gonzalez was funded by ISCIII (PI19/00658), cofunded by ERDFA way to make Europe. Dr Gonzalez-Calle is funded by ISCIII (CM20/00039). Dr. Nombela-Franco holds a research grant (INT19/00040) from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Instituto de Salud Carlos III). Dr. Tirado-Conte holds a research-training contract “Rio Hortega” (CM21/00091) from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Instituto de Salud Carlos III).