Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome (OMAS) is a movement disorder whose origin is frequently paraneoplastic or parainfectious. It is characterised by acute or subacute rapid, multi-directional saccades associated with truncal ataxia and diffuse myoclonus; to a lesser extent, dysarthria, appendicular ataxia, and/or deterioration in level of consciousness also appear. In 50% of the cases, neurological symptoms manifest before a tumour is diagnosed and neuroimaging studies display no alterations. Adults with paraneoplastic OMAS show partial or no response to immunomodulatory therapy; in these patients, relapses are frequent and may lead to fatal diffuse encephalopathy. Furthermore, some patients experiencing relapses will need to resume treatment. OMAS is an extremely rare and probably immune-mediated disorder. Lack of clinical trials means that no treatment guidelines are available to date.1–16 We present a case of recurrent OMAS in an immunocompetent adult whose symptoms resolved with IV methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide pulse therapy (MCPT).

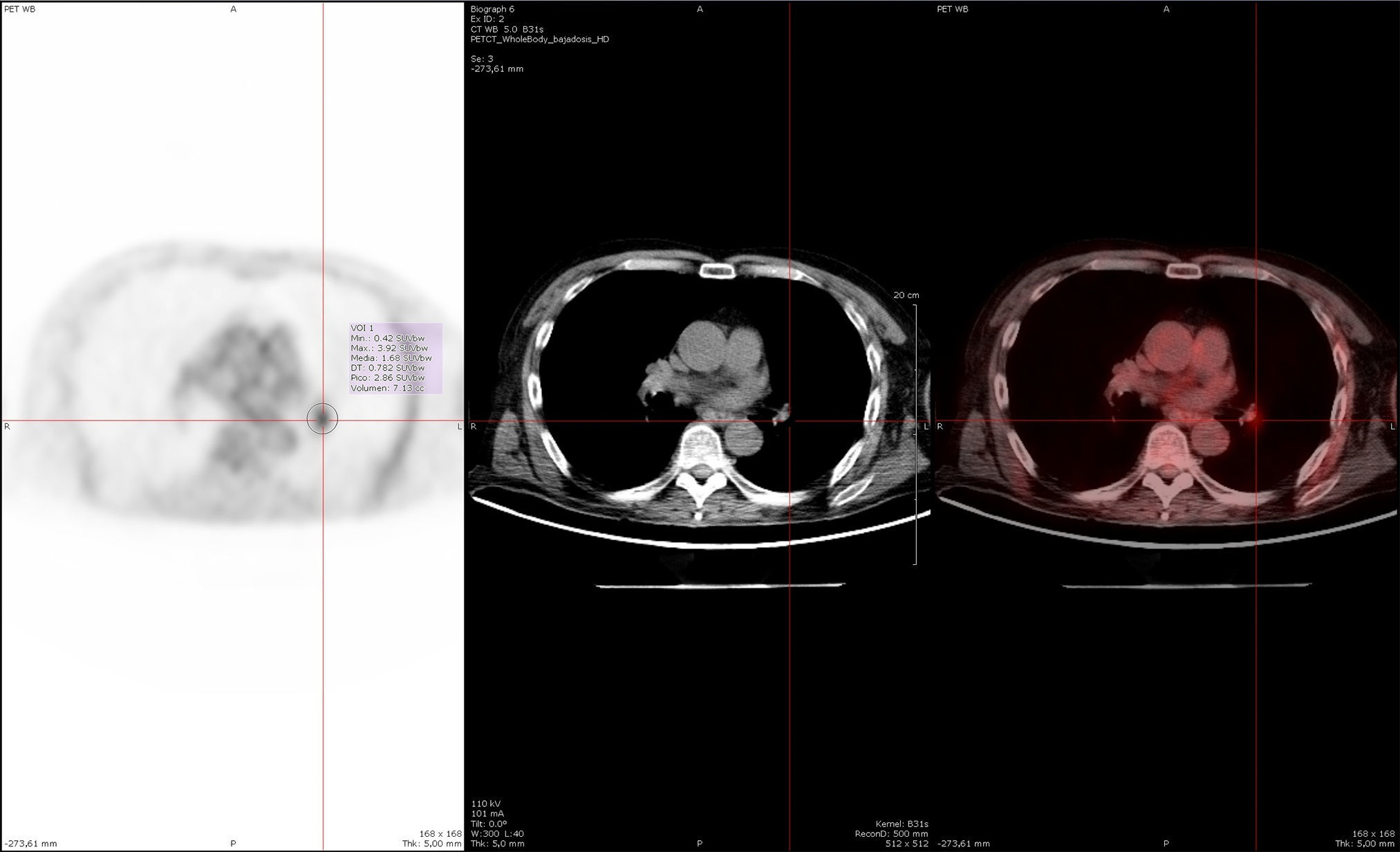

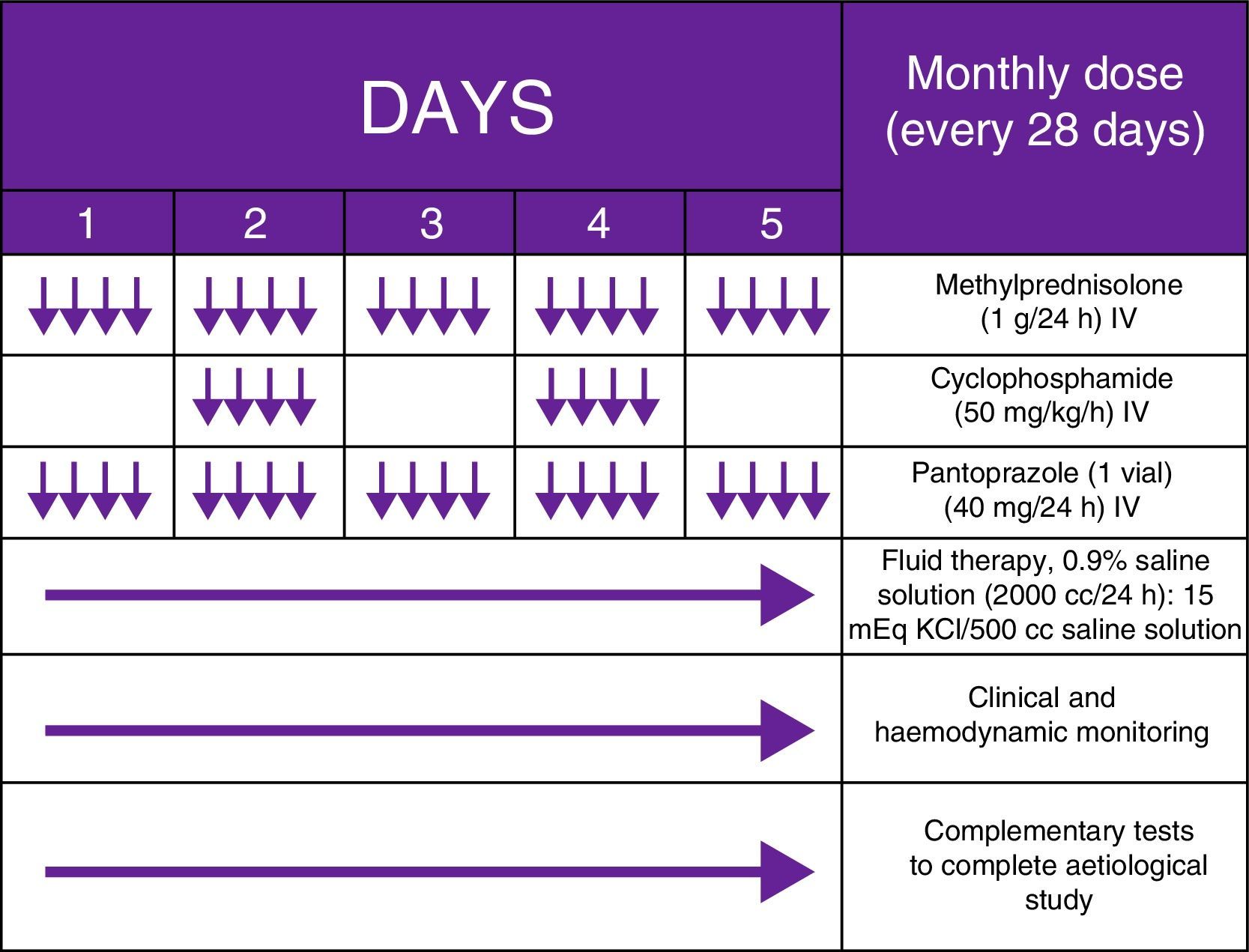

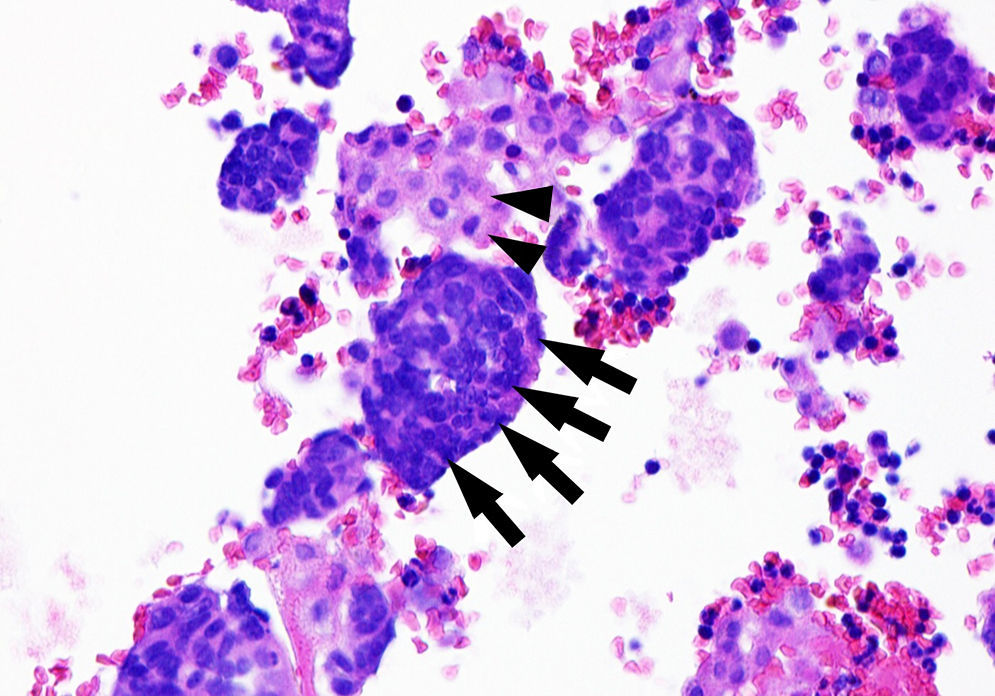

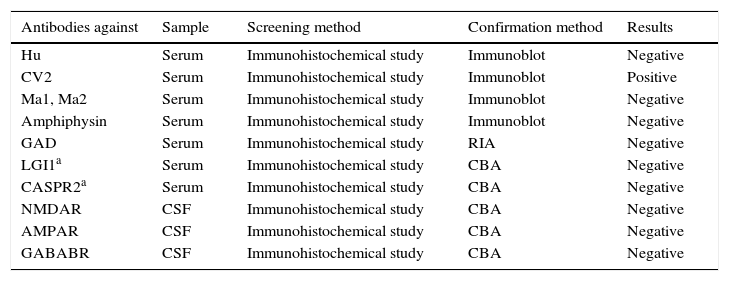

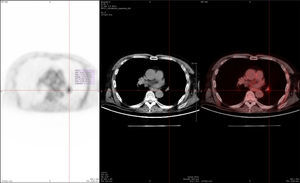

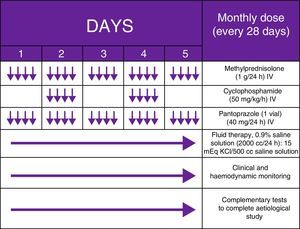

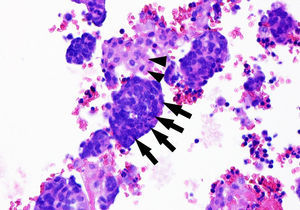

Our patient was a 62-year-old man with a history of severe use of tobacco (94 pack-years) and alcohol (3-4 glasses of whisky/day) who came to the emergency department due to a 2-week history of ataxic gait with alternating bilateral lateropulsion resulting in falls. Since cerebellar involvement was suspected, he was admitted to the neurology department and underwent a complete analysis and a thorough radiological study. During the hospital stay, our patient's state worsened: he exhibited fluctuations in the level of consciousness, incoherent thinking, visual hallucinations, jargon aphasia, dysarthria, psychomotor agitation, multifocal myoclonus, and binocular nystagmus, which was horizontal-rotatory during the first few days and multidirectional thereafter (Appendix A. Additional material [video available online]). A general analysis ruled out a toxic, metabolic, or infectious aetiology; a brain MRI scan, a whole-body PET/CT study (Fig. 1), and testicular ultrasound revealed no signs of tumours. Our patient tested positive for anti-CV2 antibodies (Table 1) and the EEG displayed generalised grade 2 delta activity. Given the clinical suspicion of OMAS and the lack of response to megadose corticosteroid therapy (1g/day for 5 days) with 2 subsequent cycles of IV immunoglobulins (0.4g/day for 5 days), we decided to administer MCPT on a monthly basis (Fig. 2) based on the protocols described in paediatric literature; this treatment has been proven effective and significantly less costly than rituximab. Treatment achieved symptom resolution. Unfortunately, our patient experienced a relapse one year later, after reducing the medication. This time, small cell lung cancer (SCLC) was detected and confirmed by anatomical pathology studies (Fig. 3); extrathoracic metastases were also detected (pleura, liver, adrenal glands). Our patient was diagnosed with definite OMAS and died 7 months later during hospitalisation.

Whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT study conducted one year after symptom onset, after our patient's second admission to hospital. Hypermetabolic mass in the root of the left lung with a maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) of 3.92 in the interlobar region (SUVmax≥2.5 generally indicates a high probability of malignancy), with normal findings on IV contrast CT images. Suspicion of adenopathy was later confirmed with an endobronchial ultrasound-guided puncture in the hypermetabolic region, which detected no neoplasia.

Antibody test results in serum and CSF samples.

| Antibodies against | Sample | Screening method | Confirmation method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu | Serum | Immunohistochemical study | Immunoblot | Negative |

| CV2 | Serum | Immunohistochemical study | Immunoblot | Positive |

| Ma1, Ma2 | Serum | Immunohistochemical study | Immunoblot | Negative |

| Amphiphysin | Serum | Immunohistochemical study | Immunoblot | Negative |

| GAD | Serum | Immunohistochemical study | RIA | Negative |

| LGI1a | Serum | Immunohistochemical study | CBA | Negative |

| CASPR2a | Serum | Immunohistochemical study | CBA | Negative |

| NMDAR | CSF | Immunohistochemical study | CBA | Negative |

| AMPAR | CSF | Immunohistochemical study | CBA | Negative |

| GABABR | CSF | Immunohistochemical study | CBA | Negative |

AMPAR: alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptor; CASPR2: contactin-associated protein-like 2; CBA: cell-based assay (immunohistochemical study using HEK cells [human embryonic kidney cells] transfected with the antigen); CV2 (CRMP-5-IgG): collapsin response mediator protein 5; GABABR: γ-aminobutyric acid type B receptor; GAD: glutamic acid decarboxylase; Hu (ANNA-1): type 1 antineuronal nuclear antibody; Ma1: neuron- and testis-specific protein 1; Ma2: onconeuronal antigen; NMDAR: N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. LGI1: leucine-rich glioma inactivated 1 protein; RIA: radioimmunoassay.

Cytology test of bloody pleural fluid. Cell block (haematoxylin–eosin stain) showing tumour cells (nuclear moulding with an extremely high nuclear–cytoplasmic ratio, abundant mitotic figures, and minimal cytoplasm) (arrows) intermingled with reactive mesothelial cells (more abundant, eosinophilic cytoplasm, light pink in colour) (arrowheads). The immunohistochemical study of tumour cells was positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1, which points to a primary pulmonary origin), chromogranin/synaptophysin, CD56, and Ki-67 (MIB-1) (in 57% of all neoplastic cells). These findings were compatible with infiltration or metastasis of small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung.

Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes (PNS) are extremely rare, with an incidence rate below 1% in patients with cancer. In adults, the types of cancer most frequently associated with PNS are SCLC (anti-Hu or anti-CV2 antibodies) and breast cancer (anti-Ri antibodies). On the other hand, SCLC represents 20% of all malignant lung tumours. This type of tumour, which originates in Kulchitsky cells, is normally central and frequently associated with mediastinal adenopathies. SCLC is very aggressive and spreads to extrathoracic structures very easily (95% of the cases). The percentage of patients with SCLC who develop PNS is estimated at 3%.1–18 PNS progress rapidly, frequently resulting in irreversible neuronal damage in a few weeks. Due to their relapsing-remitting course, they have a poor prognosis. Motor and cognitive-behavioural sequelae constitute the main challenge for patient management in the middle and long term. Early treatment is therefore essential. Management of patients with OMAS should target the cancer and include immunotherapy. Corticosteroids are the most effective alternative to OMAS. Other available treatments include cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, ciclosporin A, rituximab, gamma globulins, and plasmapheresis. However, relapses are frequent after medication is reduced or discontinued. Multimodal treatment is therefore recommended to prevent relapses and improve long-term prognosis.1–16 Good response to MCPT has been described in paediatric patients with OMAS,19 but not in adults. After a thorough literature search on PubMed (MEDLINE), we can state that ours is the first reported case of an adult whose recurrent OMAS resolved thanks to MCPT. We therefore suggest MCPT as an early treatment option in cases of OMAS refractory to corticosteroids and immunoglobulins. This may improve quality of life and reduce neurological and cognitive sequelae occurring in up to 80% of these patients.11,20 Analytic and experimental studies with greater sample sizes would provide invaluable data on the effectiveness of this combined immunosuppressant treatment in adults.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Drs José Tejeiro Martínez, Francisco Cabrera Valdivia, Victoria Galán Sánchez-Seco, Carla Sonsireé Abdelnour Ruiz, María Molina Sánchez, María Henedina Torregrosa Martínez, and Pilar Hernández Navarro.

Please cite this article as: León Ruiz M, Benito-León J, García-Soldevilla MA, Rubio-Pérez L, Parra Santiago A, Lozano García-Caro LA, et al. Biterapia inmunosupresora efectiva e innovadora en un síndrome opsoclono-mioclono-ataxia paraneoplásico e inusual del adulto. Neurología. 2017;32:122–125.

This study was presented in poster format at the 66th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology (Valencia, November 2014).