Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, that is, the deposition of β-amyloid, especially Aβ40, on the walls of small cerebral and leptomeningeal arteries, is a very frequent finding both in patients with Alzheimer disease and in cognitively healthy elderly individuals.1–3 An anatomical pathology study provides the definitive diagnosis. However, finding typical abnormalities in a brain MRI, plus detecting cerebral amyloid disease by means of PiB-PET or by measuring the decrease in Aβ-40 and Aβ-42 in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), eliminates the need for a histopathological study.3 One infrequent presentation known as inflammatory amyloid angiopathy (IAA) is characterised by the development of perivascular inflammatory infiltrates associated with amyloid angiopathy. Its clinical symptoms typically include rapidly progressive cognitive impairment, epileptic seizures, and headache. This entity was described in the 1980s as an isolated type of vasculitis of the central nervous system (CNS). However, with the appearance of the first cases of Aβ-induced meningoencephalitis, it began to be regarded as a different entity in which the β-amyloid deposited on the vascular walls acts as an antigen.4–6 This hypothesis has been reinforced by the description of anti-Aβ-42 antibodies in the CSF and cerebral parenchyma as well as by new histopathology studies.7–9

Here, we present a case of IAA and Alzheimer disease in which we concluded that biopsy was not necessary to assign a diagnosis.

An 82-year-old man was seen by the emergency department for head trauma caused by a fall the same day. Relevant medical history included multiple facial basal cell carcinomas that were surgically removed and treated with radiation in 2003 due to local recurrence. While in the emergency department, the patient displayed disorientation with no focal neurological signs. CT revealed haemorrhagic foci and extensive bilateral white-matter hypodensities that suggested underlying neoplasia. The patient was admitted to the neurosurgery department and treated with dexamethasone 4mg/8h.

Roughly 6 months before being admitted, the patient had begun to experience memory lapses; 3 months after that, he had developed apathy, hand tremor, and disorientation. His condition had deteriorated considerably by the week before he was admitted, and he needed supervision when showering.

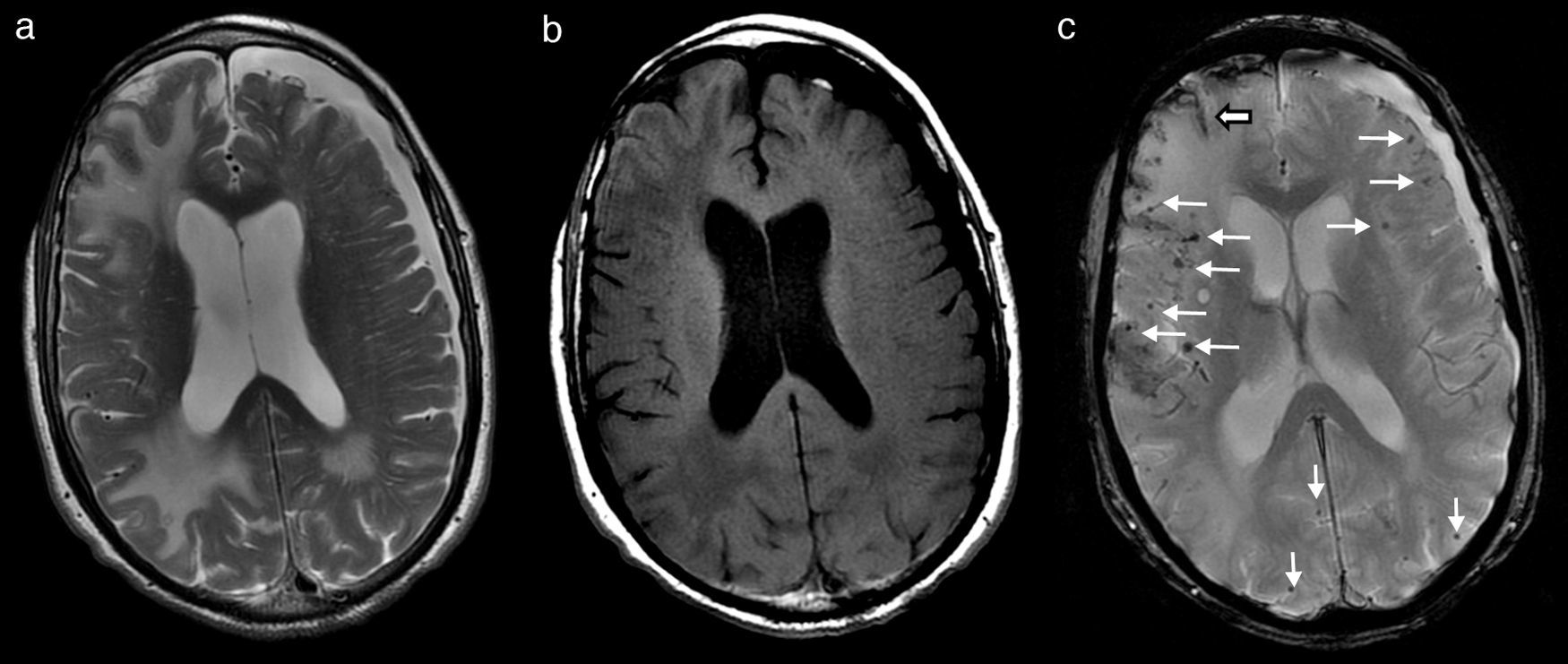

Over the first few days of hospitalisation, his cognitive function grew worse and he experienced agitation episodes and night-time hallucinations. After a week of hospitalisation and treatment with dexamethasone, both his tremor and cognitive function began to improve significantly; his family found his condition to be better than it was before he was admitted. At that time, we performed a brain MRI which revealed large areas of vasogenic oedema in occipital-parietal and frontal regions of the right hemisphere, with more limited areas in the left hemisphere (Fig. 1a and b). Multiple millimetre-sized foci of haemosiderin deposition, predominantly cortical and diffuse, were also present (Fig. 1c). In light of these findings, his doctors consulted with the neurology department.

Brain MRI showing lesions that are hyperintense in T2 (a) and hypointense in T1 (b), corresponding to large areas of vasogenic oedema in right parietal-occipital and frontal regions, with more limited areas in the parietal-occipital region of the left hemisphere. T2*-weighted gradient echo sequence (c) revealed multiple millimetre-sized foci of haemosiderin deposition that were predominantly cortical and diffuse (fine arrows). There were also traces of subarachnoid leptomeningeal siderosis (wide arrow). Cortical and subcortical atrophy with marked degenerative dilation of perivascular Virchow-Robin spaces and a left frontoparietal subdural hygroma were present.

Neurological examination at that time showed marked symmetrical bilateral parkinsonism, partial disorientation in all 3 spheres, pronounced attention deficit, and moderate impairment of all cognitive functions. His score on the MMSE was 13/30.

Once the syndromic diagnosis of subacute dementia had been established, the findings from the examination and brain MRI led doctors to propose differential diagnosis for IAA, isolated CNS vasculitis, vasculitis due to radiotherapy-induced necrosis, primary CNS lymphoma, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. We therefore performed a biochemistry test, a full blood count, vitamin B12 test, thyroid hormone profile, autoimmunity test, and serology tests for HIV and syphilis. All results were normal. Lumbar puncture with fluid analysis yielded slightly elevated CSF protein (0 cells; glucose 61mg/dL; protein 56mg/dL), with a normal IgG index and absence of oligoclonal bands. We measured CSF levels of Aβ-42 (251pg/mL [>500pg/mL]), phosphorylated tau (53pg/mL [<85pg/mL]), and h-tau (1520pg/mL [<350pg/mL]).

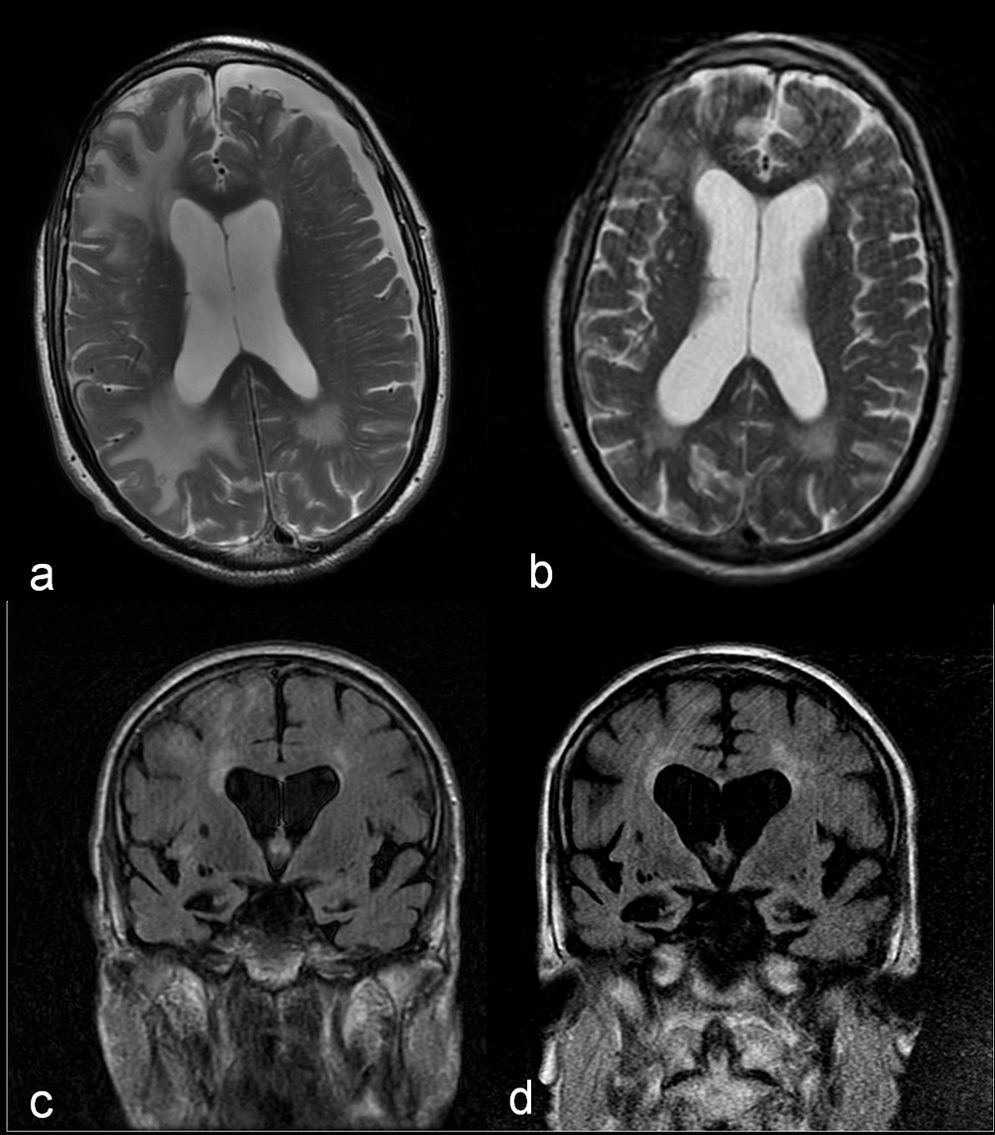

These results, together with the good initial response to dexamethasone, pointed to IAA as the primary diagnostic possibility. It was therefore decided to forego the biopsy and administer a 1g bolus of 6-methylprednisolone intravenously over 5 days, followed by progressively decreasing doses of prednisone. The patient gradually recovered at home and was able to resume previous activities. A month and a half after syndrome onset, we performed a new brain MRI which revealed a noticeable decrease in the size of the white-matter lesions (Fig. 2a and b). However, each attempt at reducing the dose of prednisone to less than 10mg/day elicited poorer cognitive function followed by partial recovery when that dose was increased. At 7 months after discharge, the patient's brain MRI showed that lesions remained stable and that hippocampal atrophy had progressed (Fig. 2c and d). The patient displays slowly progressing cognitive impairment (MMSE 11/30). The assigned diagnosis was probable IAA and probable Alzheimer disease.

Comparison of axial T2-weighted images showing a noticeable decrease in the size of white-matter lesions and resolution of the subdural hygroma between the acute phase (a) and a month and a half later (b). Comparison of coronal FLAIR sequences showing progression of cerebral and hippocampal atrophy and secondary ventricular dilation between the acute phase (c) and 6 months later (d).

The diagnosis of IAA is a clearly given histological confirmation. However, increasing numbers of authors advocate diagnosis based on a compatible clinical and radiological profile (partially reversible lesions that are hyperintense on T2/FLAIR images and ADC mapping and hypointense in T1, sometimes with contrast uptake and microhaemorrhages visible on gradient echo sequence). These findings must exclude other types of leukoencephalopathy and be supported by the presence of a marker for amyloid deposition (for example, low Aβ-42 in CSF).1,7,8,10–13 Treatment in the acute phase comprises corticosteroid megadose followed by down-titration. At least 25% of these patients either do not respond to corticosteroids or experience relapses; they may respond to immunosuppressant treatment.10,14

In our case, the time elapsed between symptom onset and providing treatment may explain why the patient's recovery was only partial. On the other hand, the slow disease progression despite corticosteroid treatment, plus the significant and progressive cerebral and hippocampal atrophy suggests Alzheimer disease associated with IAA.15

Please cite this article as: Vázquez-Costa JF, Baquero-Toledo M, Sastre-Bataller I, Mas-Estellés F, Vílchez-Padilla JJ. Angiopatía amiloide inflamatoria. Neurología. 2014;29:254–256.

This case was presented at the case report contest held by the Valencian Society of Neurology.