Fatigue in multiple sclerosis (MS) is defined as the lack of physical and/or mental energy perceived by the individual that interferes with normal activities. It is the most common symptom in MS, present in up to 90% of people with MS. Fatigue along with disability, depression, cognitive impairment, and disease-modifying therapy (DMT) affect quality of life (QoL).

MethodWe designed a prospective observational study in patients with MS and DMT of moderate efficacy to assess the association between fatigue and the epidemiological, clinical, and pharmacological aspects that influence in the QoL. We analysed variables related to patients, disability, fatigue (MFIS), clinical and radiological activity, depression (BDI), cognitive impairment (SDMT), and QoL (EQ-5D).

Resultswe included 91 people, 65.9% women, mean age 43.9 years. The DMT were: 27.4% interferon-β, 15.38% glatiramer acetate, 9.89% teriflunomide, and 47.25% dimethyl fumarate. The median of the EDSS was 1.5 points. 40.9% have presented fatigue, 36.3% cognitive deterioration and 30.7% of the patients depression.

ConclusionsPatients with fatigue are older, more disabled, have a higher prevalence of depression and worse QoL. Evolution time, relapses, MRI lesion load, and DMTs are not associated with fatigue. Fatigue is a frequent symptom in patients with MS that influences in the QoL, hence the importance of its diagnosis and treatment.

La fatiga en la esclerosis múltiple (EM) se define como la falta de energía física y/o mental percibida por el individuo e interfiere en las actividades habituales. Es el síntoma más común en la EM, presente hasta en el 90% de las personas con EM. La fatiga junto con la discapacidad, la depresión, el deterioro cognitivo y el tratamiento modificador de la enfermedad (TME) condicionan la calidad de vida (CdV).

MétodoDiseñamos un estudio prospectivo observacional en pacientes con EM y con TME de moderada eficacia para valorar la asociación entre la fatiga y los aspectos epidemiológicos, clínicos y farmacológicos que influyen en la CdV. Analizamos variables relacionadas con los pacientes, la discapacidad, la fatiga (MFIS), la actividad clínica y radiológica, la depresión (BDI), el deterioro cognitivo (SDMT) y la CdV (EQ-5D).

Resultadosincluimos 91 personas, 65,9% mujeres, 43,9 años de edad media. Los TME han sido: 27,4% interferón-β, 15,38% acetato de glatirámero, 9,89% teriflunomida y 47,25% dimetilfumarato. La mediana de la EDSS fue de 1,5 puntos. El 40,9% han presentado fatiga, el 36,3% deterioro cognitivo y el 30,7% de los pacientes depresión.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con fatiga tienen más edad, mayor discapacidad, mayor prevalencia de depresión y peor CdV. El tiempo de evolución, las recaídas, la carga lesional en RM y los TME no se asocian a la fatiga. La fatiga es un síntoma frecuente en pacientes con EM que influye en la CdV, de ahí la importancia de su diagnóstico y tratamiento.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that causes demyelination and axonal neurodegeneration.1 Its aetiology is not fully understood, but involves a complex interaction between genetic and environmental factors.2 The most frequent presentation and clinical course is the relapsing-remitting form (RRMS), in which patients present relapses as a result of inflammatory disease activity, and axonal degeneration leads to cumulative progression of disability.3 Multiple disease-modifying treatments (DMT) are available, and are currently classified as moderate- or high-efficacy treatments, according to the risk/benefit profile observed in pivotal trials.4 Furthermore, symptomatic treatments are often prescribed for certain clinical manifestations influencing the quality of life (QoL) of patients with MS. Such symptoms as fatigue, depression, spasticity, and cognitive impairment are a constant in the management of these patients, and constitute a genuine challenge in their treatment at the neurology consultation.

The drugs used to treat MS with mild to moderate activity at onset include injectable DMTs (interferon beta, glatiramer acetate [GA]); these were the first drugs to appear for MS treatment and, as a result, extensive clinical evidence is available on their safety and effectiveness. Oral DMTs of moderate efficacy (teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate [DMF]) appeared later; these drugs do not present the secondary effects inherent to parenteral administration, and do not cause flu-like symptoms, which are so common with interferon beta. In a cohort study with 18 years of follow-up, the median time to discontinuation of the first injectable DMT was 8.6 years, with the main reasons for suspension being real or perceived loss of efficacy and the appearance of such secondary effects as flu-like symptoms, depression, fatigue, and injection site reactions.5

Fatigue in MS is defined as a perceived lack of physical and/or mental energy that interferes in the patient’s daily activities.6 It is the most common symptom of MS, affecting up to 80%–90% of patients at some point over the course of the disease.7,8 Given the diversity of symptoms associated with fatigue and the complexity of identifying the pathophysiological mechanism, a distinction is drawn between primary fatigue, which is attributed directly to MS as a result of immune dysregulation presenting with demyelination, axonal loss, or neuroendocrine alterations9; and secondary fatigue, which is an indirect result of such MS symptoms as sleep disorders, depression, apathy, and disability, or DMTs themselves.10 Fatigue has 2 components, physical fatigue and cognitive fatigue. Physical fatigue is characterised by a reduction in motor performance during sustained muscle activity. Cognitive fatigue is defined as a decrease in cognitive performance, with difficulty concentrating, memory loss, and emotional instability, and appears early in MS regardless of the degree of physical disability.11

Fatigue is more severe and disabling in MS than in healthy individuals and in other chronic diseases.12 Approximately one-third of patients consider fatigue to be their most disabling symptom.13 Despite the high prevalence and potential impact of MS-associated fatigue, its aetiology is poorly understood and few therapeutic options are available.14 Although they do not always achieve the desired benefit, we may prescribe drugs including amantadine, modafinil, amphetamine-like stimulants (methylphenidate), or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, as well as cognitive/behavioural techniques (relaxation, physical exercise, strength training, mindfulness, yoga, tai chi) that can improve fatigue.15

Depression is frequently observed in MS; it is diagnosed in approximately 50% of patients,16 and is one of the main determinants of their QoL.17 Major depressive disorder is up to twice as prevalent in patients with MS, with a sex- and age-adjusted hazard ratio of 2.3; there are no differences between sexes, but prevalence is greater in young adults under 45 years of age.18 Depression is often associated with fatigue, with some authors suggesting that onset of fatigue and anxiety may be a risk marker for depression.19 Fatigue in patients with MS is associated with depression, as well as such other variables as emotional distress, disability,20 cognitive impairment,21 and other comorbidities including sleep disorders, pain, spasticity, nocturia, and restless legs syndrome.

Among the determinants of QoL in MS, depression, fatigue, and level of disability as measured with the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) have been identified as independent predictors of QoL. Presence of fatigue negatively impacts QoL,22,23 with an impact on work, social, and family life.24

Some authors have suggested that DMT improves fatigue by reducing the inflammatory response; therefore, fatigue and depression may be associated with immunological factors. Studies of the effects of DMT in patients with MS and depression have not reported conclusive results. DMTs have shown benefits for reducing fatigue,25,26 although certain DMTs have been found to increase fatigue and the risk of depression.27,28

Patient-reported outcome measures and clinical assessment scales must be administered to assess the well-being of patients with MS and to enable development of a specific treatment strategy. DMTs can influence aspects related to relapses, disability progression (EDSS score), and other variables that largely determine QoL. Furthermore, certain issues may be overlooked if targeted questions are not asked at consultations; specifically, these are fatigue, depression, cognitive impairment, and QoL.

The purpose of this study is to determine the prevalence of fatigue in patients with RRMS, and its relationship with demographic, clinical, and pharmacological factors affecting QoL, and to identify any differences in these variables depending on the DMTs received.

Material and methodsWe conducted a prospective, observational, open-label, non-randomised study at the demyelinating diseases unit of a neurology department. The study included patients with MS attending scheduled follow-up consultations at the unit, who met the selection criteria and agreed to participate in the study. Patients were recruited consecutively during the year 2021. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18–60 years, diagnosed with MMRS and under treatment for at least 6 months with injectable (interferon-βa [IFN] or GA) or oral DMTs (DMF or teriflunomide) of moderate efficacy, in accordance with clinical practice guidelines and the indications listed in the summary of product characteristics for each drug. We excluded patients receiving high-efficacy drugs, with a view to achieving a more homogeneous sample and avoiding biases related to these drugs, which are prescribed to patients with greater disease activity and progression and more severe disability. We also excluded patients with concurrent disease processes (anaemia, uncontrolled hyperthyroidism).

We collected data on the following demographic variables: age, sex, family history of MS, level of schooling, smoking, MS progression variables (age of onset, progression time, localisation of the first relapse), and variables related to disease activity (annualised relapse rate [ARR], disability [EDSS], manual dexterity in the Nine-Hole Peg Test [9HPT],29 and walking speed in the Timed 25-Foot Walk [T25FW]30). Other data collected included neuroimaging results from the last MRI study performed (number of Gd + lesions and T2 lesions), current DMT, and vitamin D levels.

Patients completed the 21-item Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS), which evaluates patient perception of fatigue over the last 4 weeks, assessing physical (9 items), cognitive (10 items), and psychosocial components (2 items). Each item is scored from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always), with a maximum possible overall score of 84. The physical, cognitive, and psychosocial components are scored 0–36, 0–40, and 0–8, respectively. Higher scores indicate greater impact of fatigue in patients with MS.15 Presence of fatigue was established with a cut-off score of 38 points.31 The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to establish the presence and severity of depression.32 The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)33 was used to assess cognitive impairment, and QoL was evaluated with the 5-dimension EuroQoL quality of life instrument (EQ-5D) and the EuroQoL Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS). The EQ-5D measures 5 domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, and returns a health status index score. The EQ-VAS records patients’ self-reported health status on a scale from 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health).34

Statistical analysisAll data were analysed using the SPSS® software for Windows, version 28.0.1.0 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data were analysed with means and standard deviations (SD), in the case of continuous variables, and percentages, for categorical variables. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .05. Comparisons between the fatigue and non-fatigue groups were made using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, for numerical variables, and the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, for qualitative variables. Variables showing significant differences between groups were treated as potential confounders, and a logistic regression analysis was conducted to quantify their effect on other variables and on fatigue.

ResultsThe study included 91 patients diagnosed with RRMS according to the 2017 McDonald criteria, who attended scheduled follow-up consultations in 2021 and were under treatment with moderate-efficacy DMTs at the time of recruitment. Of the 91 participants, 60 (65.9%) were women and 31 were men (34.1%). Patients’ mean age (SD) at admission was 43.9 (11.1) years. Family history of epilepsy was recorded in 10.9% of patients. Thirty-four percent were active smokers. Nineteen patients (20.9%) had primary education only, 29 (31.9%) had secondary education, 4 (4.3%) had completed high school, and 39 (42.9%) had university education. Regarding clinical characteristics, the mean age at disease onset was 32.23 (10.4) years, and the mean disease progression time was 140 months. The most frequent form of onset was spinal (30.7% of cases), followed by optic neuritis in 24.2%. Patients had previously received a mean of 0.4889 (0.74) DMTs. By the specific DMT received, 25 patients (27.4%) were under treatment with IFN, 14 (15.38%) with GA, 9 (9.89%) with teriflunomide, and 43 (47.25%) with DMF.

The median EDSS score was 1.5 (range, 0–6). Patients presented a mean of 0.04 (0.2) relapses in the 6 months prior to study inclusion and 0.33 (0.5) in the last 2 years. T2 lesion load was fewer than 9 lesions in 17.08% of patients, 9−20 lesions in 41.46%, and more than 20 lesions in 41.46%. Neuroimaging revealed a mean of 0.13 (0.5) Gd + lesions.

According to MFIS scores, 40.9% of patients presented fatigue, with mean scores of 15.42 (9.8) in the physical component, 15.04 (10.27) in the cognitive component, and 3.21 (2.54) in the psychosocial component. The mean SDMT score was 43.13 (13.30) correct responses. According to these results, 36.26% of patients presented cognitive impairment. The mean BDI score was 10.67 (8.7) points, with 30.7% of patients presenting some degree of depression (mainly mild depression). Finally, the mean EQ-5D score was 1.72 (1.52) (a score of 0 indicates the best possible QoL and 5 the worst possible QoL). By EQ-5D dimension, no problems were reported in mobility in 70% of cases, self-care in 93.33%, usual activities in 65.56%, and anxiety/depression in 56.67% of patients. The mean EQ-VAS score (0–100) was 70.57 (21.42) points.

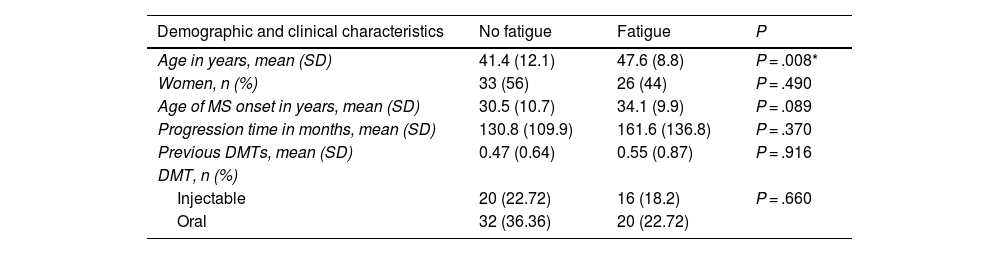

To study factors potentially associated with fatigue, patients were divided into 2 groups (fatigue and non-fatigue) according to MFIS score. Demographic and clinical variables were compared between groups to identify any differences (Table 1). We observed no association between presence of fatigue and level of schooling (P = 0.49), smoking (P = .11), family history of MS (P = .24), or location of the first relapse (spinal, optic neuritis, sensory, brainstem) (P = .366).

Demographic and clinical data from patients with and without fatigue.

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | No fatigue | Fatigue | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 41.4 (12.1) | 47.6 (8.8) | P = .008* |

| Women, n (%) | 33 (56) | 26 (44) | P = .490 |

| Age of MS onset in years, mean (SD) | 30.5 (10.7) | 34.1 (9.9) | P = .089 |

| Progression time in months, mean (SD) | 130.8 (109.9) | 161.6 (136.8) | P = .370 |

| Previous DMTs, mean (SD) | 0.47 (0.64) | 0.55 (0.87) | P = .916 |

| DMT, n (%) | |||

| Injectable | 20 (22.72) | 16 (18.2) | P = .660 |

| Oral | 32 (36.36) | 20 (22.72) |

DMT: disease-modifying treatment; MS: multiple sclerosis; SD: standard deviation.

Mean vitamin D level was 25.66 ng/mL in patients without fatigue and 22.50 ng/mL in those with fatigue; this difference was not significant (P = .319). We also observed no association between presence of fatigue and the use of the different DMTs (P = .7167; Fig. 1).

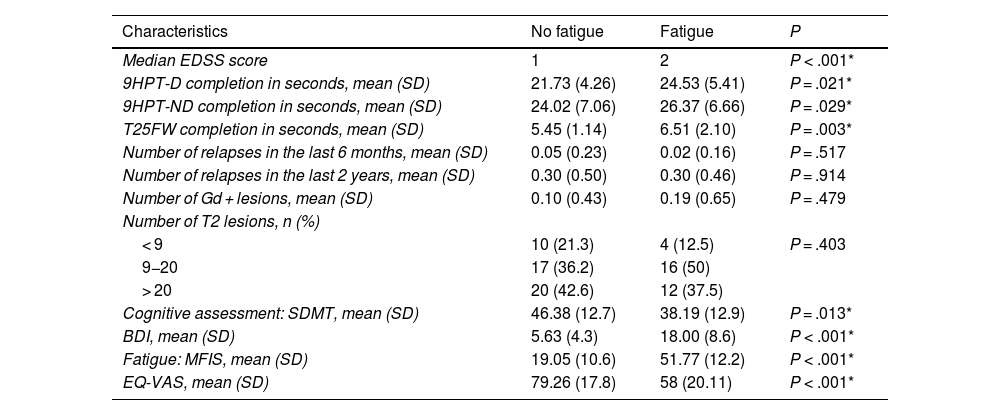

Table 2 presents clinical data on disability (EDSS), 9HPT and T25F performance, and radiological characteristics. The non-fatigue group presented lower prevalence of cognitive impairment (26%, vs 73% in the fatigue group; P = .0418). Patients with fatigue scored higher on the depression scale: 3.8% of patients without fatigue presented depression, compared to 69.4% of those with fatigue (P < .00001). Depression was severe in 13.9% of patients with fatigue, moderate in 19.4%, mild in 36.1%, and absent in 30.6%. The drugs used to treat fatigue in our series were amantadine/modafinil in 11 patients (12%) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in 9 (9.8%).

Data on clinical activity, disability, cognitive status, mood, fatigue, quality of life, and radiological findings in patients with multiple sclerosis with or without migraine.

| Characteristics | No fatigue | Fatigue | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median EDSS score | 1 | 2 | P < .001* |

| 9HPT-D completion in seconds, mean (SD) | 21.73 (4.26) | 24.53 (5.41) | P = .021* |

| 9HPT-ND completion in seconds, mean (SD) | 24.02 (7.06) | 26.37 (6.66) | P = .029* |

| T25FW completion in seconds, mean (SD) | 5.45 (1.14) | 6.51 (2.10) | P = .003* |

| Number of relapses in the last 6 months, mean (SD) | 0.05 (0.23) | 0.02 (0.16) | P = .517 |

| Number of relapses in the last 2 years, mean (SD) | 0.30 (0.50) | 0.30 (0.46) | P = .914 |

| Number of Gd + lesions, mean (SD) | 0.10 (0.43) | 0.19 (0.65) | P = .479 |

| Number of T2 lesions, n (%) | |||

| < 9 | 10 (21.3) | 4 (12.5) | P = .403 |

| 9−20 | 17 (36.2) | 16 (50) | |

| > 20 | 20 (42.6) | 12 (37.5) | |

| Cognitive assessment: SDMT, mean (SD) | 46.38 (12.7) | 38.19 (12.9) | P = .013* |

| BDI, mean (SD) | 5.63 (4.3) | 18.00 (8.6) | P < .001* |

| Fatigue: MFIS, mean (SD) | 19.05 (10.6) | 51.77 (12.2) | P < .001* |

| EQ-VAS, mean (SD) | 79.26 (17.8) | 58 (20.11) | P < .001* |

9HPT-D: Nine-Hole Peg Test, dominant hand; 9HPT-ND: Nine-Hole Peg Test, non-dominant hand; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; EQ-VAS: EuroQoL Visual Analogue Scale; MFIS: Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; SD: standard deviation; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test; T25FW: Timed 25-Foot Walk.

Fig. 2 compares the mean MFIS total and component scores in the fatigue and non-fatigue groups; differences between groups were significant in all cases (P < .001). QoL was lower (higher EQ-5D scores) in the fatigue group. Significant differences were observed in the dimensions mobility, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, but not in the dimension self-care (Fig. 3).

Eighty percent of patients with fatigue presented moderate or severe problems in at least 2 dimensions of the EQ-5D. Fig. 4 shows the distribution of the number of dimensions affected in each group. EQ-VAS scores were lower in the fatigue group than in the non-fatigue group (58 [20.1] vs 79.2 [17.8]; P < .001).

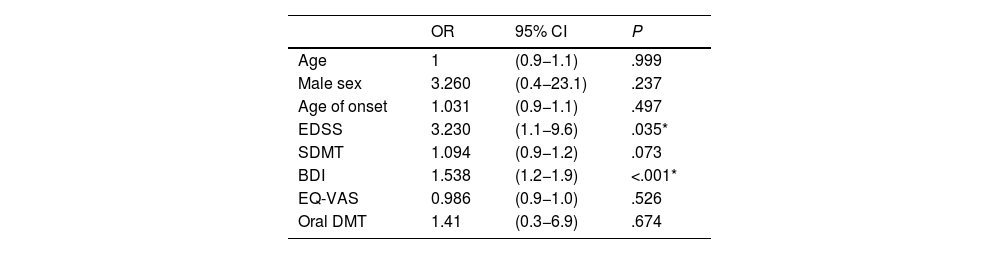

Logistic regression was used to analyse the different variables potentially influencing the presence of fatigue in patients with MS, adjusting for sex and age; only EDSS score (odds ratio: 3.2) and depression as measured with the BDI (odds ratio: 1.5) were identified as independent risk factors for fatigue (Table 3).35

Age- and sex-adjusted logistic regression analysis of the relationship between fatigue and clinical and demographic variables.

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | (0.9−1.1) | .999 |

| Male sex | 3.260 | (0.4−23.1) | .237 |

| Age of onset | 1.031 | (0.9−1.1) | .497 |

| EDSS | 3.230 | (1.1−9.6) | .035* |

| SDMT | 1.094 | (0.9−1.2) | .073 |

| BDI | 1.538 | (1.2−1.9) | <.001* |

| EQ-VAS | 0.986 | (0.9−1.0) | .526 |

| Oral DMT | 1.41 | (0.3−6.9) | .674 |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CI: confidence interval; DMT: disease-modifying treatment; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; EQ-VAS: EuroQoL Visual Analogue Scale; OR: odds ratio; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test.

Fatigue is one of the most frequent symptoms of MS, and has a considerable impact on QoL. MS prevalence is higher in women, who accounted for 65.9% of patients in our series; similar percentages are reported in the literature.36 Age has been proposed as a risk factor for fatigue in these patients.37 The mean age in our series was 47 years in the fatigue group, and no differences were observed between groups in terms of age of onset or disease progression time. Currently, there is no consensus between published series on the influence of age or sex on the presence of fatigue in MS.9 In our sample of patients with RRMS, fatigue was unrelated to level of schooling, whereas other authors have reported greater fatigue among patients with lower education levels, particularly among older patients and those with progressive forms of MS, but not in those with relapsing forms.38 While we observed no relationship between smoking and fatigue, other authors do report an association between fatigue and lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, sedentary lifestyle), and particularly between physical activity and the psychosocial component of the MFIS.39 We observed no differences in vitamin D levels, regardless of the level of fatigue, although this association has been reported in the literature.40

Between 35% and 97% of patients with MS present fatigue, according to different studies.15,36,37 In our series, approximately 40% of patients presented fatigue. The higher prevalence rates described by other authors may be explained by the greater mean age of their patients (54 years, vs 44 in our series), longer progression times (13 vs 11 years), and especially by the higher EDSS scores (5 vs 1.5 points). Téllez et al.41 also report a higher prevalence of fatigue than in our series (55% of patients, classified according to MFIS scores), partly due to the inclusion of patients with secondary progressive MS, who, as we would expect, were older and had longer disease progression times. According to our own data, age of disease onset and progression time do not influence the presentation of fatigue; similar findings are reported by other authors.37 Analysis of the 3 MFIS components revealed similar results to those of previous studies. Fatigue in MS is associated with alterations in the physical,42,43 psychosocial,44 and cognitive components of the MFIS,45 highlighting its multifactorial and disabling impact.

Few studies have evaluated the association between fatigue and mobility problems, depression, and quality of life. In our series, disability (EDSS score) increased in line with age. Median EDSS score was 2 among patients with fatigue and 1 in the non-fatigue group. While these data are not always replicated, we believe that this may be because EDSS scores are higher in both groups.36 Fatigue is frequently associated with greater disability; however, the correlation is weaker after controlling for such variables as age, disease duration, and such other clinical factors as depression.46,47 In the study by Rooney et al.,37 64% of patients presented fatigue, which was associated with QoL, depression, cognitive performance, and sleep quality, in both progressive and non-progressive forms of MS. In the non-progressive MS group, fatigue was also associated with disability.37 Our data demonstrate that patients with fatigue present greater disability in terms of both EDSS scores and 9HPT and T25FW performance. Presence of clinical (relapses in the last 6 months or 2 years) and radiological disease activity (Gd + lesions) was not associated with the presentation of fatigue. Furthermore, T2 lesion load was similar in both groups.

The literature includes divergent results on the effect of IFN and GA on fatigue.48 The effect of DMT on fatigue has been widely studied, although results are not always consistent. Putzki et al.49 studied 320 patients, observing fatigue in 50%. Their analysis, accounting for MS subtype, disease duration, and disability, did not find an association between fatigue and treatment. Controlling clinical disease activity and inflammation appears not to significantly affect fatigue.49

Patient-reported outcome measures are increasingly used in everyday clinical practice, as they enable greater understanding of “invisible” symptoms and tailoring of treatment to each patient’s needs. A study of moderate-efficacy DMTs (IFN, GA, DMF, and teriflunomide) found that DMF and teriflunomide (oral DMTs) presented the greatest treatment satisfaction (Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication), despite greater side effects. Patients treated with teriflunomide presented poorer QoL and greater fatigue, but were also older and had higher levels of disability and depression; therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution.50 Patients receiving DMF treatment present better results than untreated patients on scales assessing QoL, fatigue, and depression.25 DMT in and of itself has not been shown to improve fatigue in patients with MS. Téllez et al.38 found no differences in the prevalence of fatigue or depression between patients with and without IFN treatment. Depression may appear or worsen as a result of IFN treatment.51 In our series, 30.7% of patients presented depression, although this was not associated with any particular drug. This rate is lower than the 68% described in the literature,41 and the 50% reported in a recent review.15 Patients with fatigue scored higher on the BDI (18 points, vs 5.63 in the non-fatigue group), with other studies reporting similar data.36,37

Not all studies have found depression to influence the appearance of fatigue,52 although this association is increasingly recognised.53,54 Depression has been identified as a contributing factor in fatigue, and vice versa. According to Bakshi et al.,46 fatigue in MS is associated with depression, even after controlling for disability; this supports the idea that depression and fatigue share neural pathogenic mechanisms. However, some authors have not identified this correlation, probably due to limitations in the inclusion of patients with low EDSS scores and less sensitive measurement of fatigue.55

Cognitive impairment is clinically relevant and occurs from early stages of MS. In our study, cognitive impairment was measured with the SDMT, which assesses patients’ concentration, attention, and information processing speed.56 SDMT results indicated impaired performance in 36.3% of patients, a somewhat lower rate than the 40% reported in other series. Another relevant finding is the lower SDMT scores in patients with fatigue (38, vs 46 in the non-fatigue group); this is consistent with other reports.57 This suggests that a high percentage of patients with MS require proper clinical follow-up due to the repercussions of the fatigue on social, work, and family life.58

Fatigue is a predictor of QoL in patients with MS. In our patients with fatigue, we observed lower EQ-5D scores for all dimensions except self-care, and lower scores on the EQ-VAS (58, vs 79 in the non-fatigue group). Previous studies confirm that fatigue is independently associated with QoL.23,36,59 Amato et al.22 suggest that fatigue is an independent predictor of QoL, with fatigue showing an inverse correlation with scores on the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 scale. Such is the impact of fatigue that it is the most frequent reason for unemployment among patients with MS.60 Fatigue is clearly the dominant factor in the final model explaining variance in QoL. Therefore, to promote improvements in this respect, it should be considered a therapeutic target. This approach should not be purely pharmacological, but rather also requires the collaboration of other professionals (nurses, rehabilitation therapists, speech therapists, occupational therapists, and psychologists), supporting the creation of multidisciplinary teams.59

This study has certain limitations: due to its observational, cross-sectional, open-label, uncontrolled design, we are unable to establish causality as it is not possible to establish the temporal relationship between variables. We are also unable to assess the effect of drugs for the treatment of fatigue, and whether switching DMTs modifies the results. As all study participants were patients with RRMS, our data cannot be extrapolated to progressive forms of the disease. Cognitive impairment was not assessed with neuropsychological test batteries that establish more detailed cognitive profiles; rather, we used the SDMT, which has been extensively validated and accepted for cognitive assessment in MS. Although our series included only 91 patients, the data obtained are useful for better understanding MS-associated fatigue.

ConclusionsFatigue is a multidimensional symptom whose appearance can be influenced by several factors. Evaluation of fatigue should be considered in the assessment of patients with MS. Our results show that fatigue is a prevalent symptom in patients with RRMS, and is associated with disability, depression, and cognitive impairment, independently of the DMT used. Fatigue has an impact on such other domains as mood, cognition, and QoL. Therefore, it should be comprehensively addressed with a range of treatment approaches. Early detection and treatment of fatigue may improve the QoL of patients with MS.

Ethical considerationsAll patients gave written informed consent to participate in this project. Participation was voluntary. All records were coded in accordance with Spanish data protection legislation (Organic Law 15-1999). Data were collected by the directors of the unit during follow-up consultations scheduled according to everyday clinical practice. The project was approved by our hospital’s biomedical research ethics committee.

This study was approved by the provincial research ethics committee of Granada, belonging to the network of ethics committees of the Andalusian public healthcare system. This committee considered and evaluated at its session of 29 June 2020 (proceedings 6/2020) the proposal of the promoter (no promoter is associated) to conduct the research study entitled: DMF-ver-1.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

R.P.M. has received consulting fees and lecture honoraria from Biogen, Genzyme, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi. These organisations had no involvement in study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; drafting of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

P.A.G.R. has no conflicts of interest to declare.

F.J.B.H. has received consulting fees and lecture honoraria from Almirall, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genzyme, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, and Teva. These organisations had no involvement in study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; drafting of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

These results are part of the doctoral thesis of R.P.M., at the University of Granada.