Diffuse encephalopathy is a common reason for in-hospital consultations with the neurology department. The aetiology and level of severity vary greatly from case to case; an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment are therefore essential.1

Hyperammonaemia may cause encephalopathy in hospital settings. It is associated with a wide range of symptoms, one of the most frequent being liver failure secondary to cirrhosis. Non-hepatic causes of hyperammonaemia in adults include use of such drugs as valproic acid or chemotherapy agents, infection by urease-producing pathogens, a recent history of surgery (ureterosigmoidoscopy, bariatric surgery), presence of a portacaval shunt, high parenteral protein intake, and inborn errors of metabolism (ornithine transcarbamylase or carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I deficiency).2,3

In patients with multiple myeloma, encephalopathy is frequently caused by high urea levels in blood, hypercalcaemia, and hyperviscosity. Encephalopathy due to hyperammonaemia is extremely rare; it is associated with high mortality and requires a high level of suspicion and early treatment.4,5

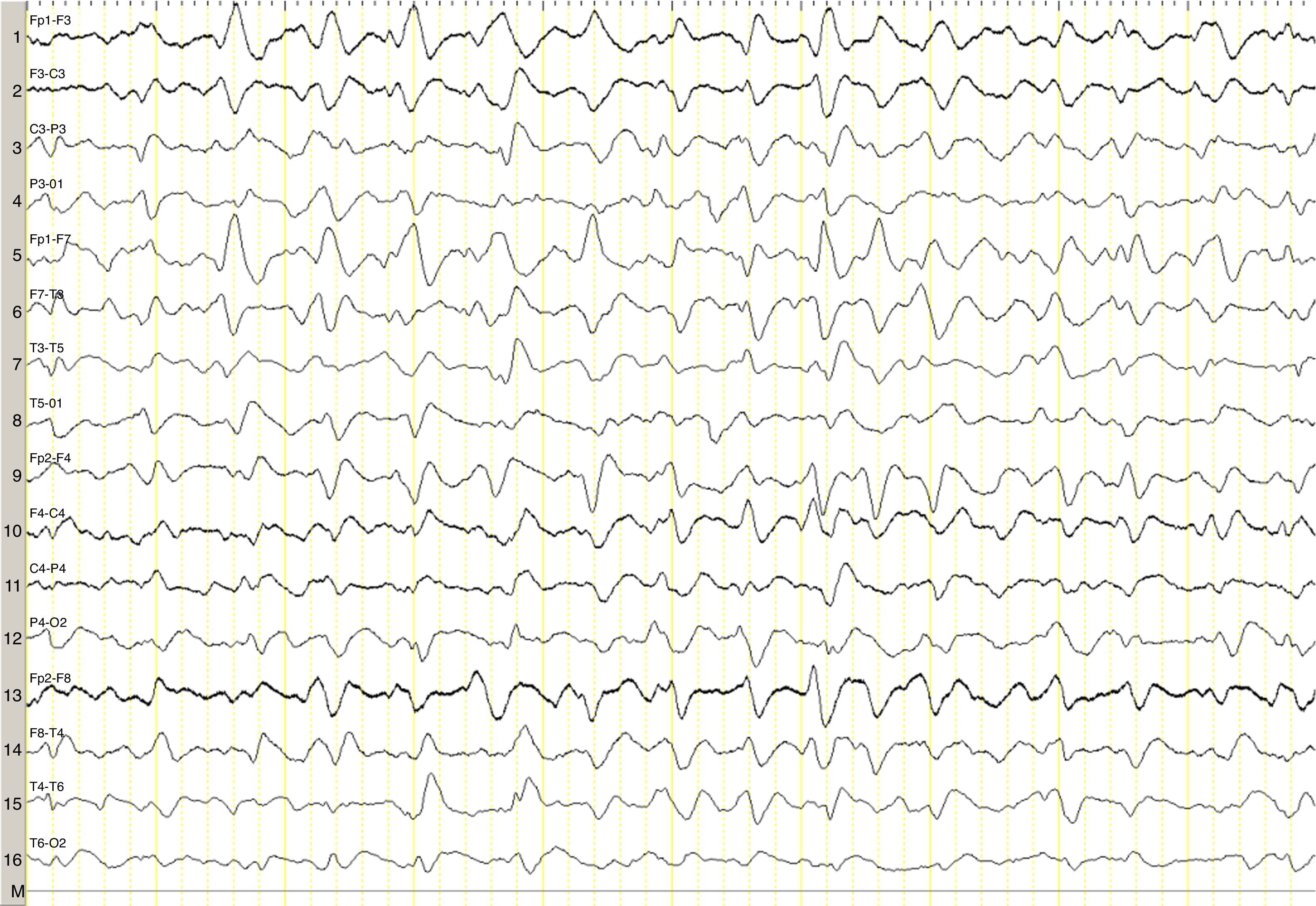

We describe the case of a 82-year-old woman with advanced multiple myeloma associated with a 2-year-history of hypergammaglobulinaemia (IgG-lambda). She was in her fifth cycle of chemotherapy with lenalidomide and dexamethasone; first-line treatment with melphalan, prednisone, and bortezomib had failed. Our patient presented a month-and-a-half long history of irritability, disorientation, decreased appetite, and drowsiness, and she was therefore admitted to the haematology department. She was assessed in the neurology department due to stupor; she displayed no associated focal neurological signs, fever, or other relevant findings. The results of the liver and coagulation profiles and the levels of creatinine, urea, calcium, and total proteins were normal. Our patient had normocytic normochromic anaemia. Results from the brain CT scan were normal. An emergency EEG revealed generalised, non-reactive slowing of background activity with generalised sharp triphasic waves in the entire EEG trace (Fig. 1). In view of these EEG findings, we requested an ammonia test which revealed high levels of ammonia at 151μmol/L (reference values 11–51μmol/L). We initiated anti-encephalopathy measures but new lines of chemotherapy were not authorised by the patient's relatives. Our patient died a month after diagnosis.

Ammonia, a toxic product of protein degradation, is incorporated into urea in the liver and excreted by the kidneys. As ammonia levels increase, it passively diffuses through the blood-brain barrier, exerting a neurotoxic effect. It is incorporated into astrocytes to form glutamine, which results in swollen astrocytes, cortical-subcortical blood flow dysregulation, and cerebral oedema in cases of acute presentation.6–8 From a clinical viewpoint, these biological changes result in alterations of the level of consciousness of varying degrees of severity. EEG results usually reveal diffuse slowing of brain activity, occasionally accompanied by presence of triphasic waves. Triphasic waves seem to be caused by abnormal activity of the thalamo-cortical circuits9,10; however, these waves are a non-specific finding since they appear in a variety of clinical conditions.11 In our case, presence of triphasic waves in the context of diffuse encephalopathy led us to complete a metabolic study, which revealed high ammonia levels.

The pathophysiology of hyperammonaemia in multiple myeloma is unknown. It has been hypothesised that leukaemia transformation may increase the likelihood of hyperammonaemia12 and plasma cell infiltration of the liver leading to porto-systemic shunting13; likewise, metabolising and degrading large quantities of immunoglobulins has been suggested to increase ammonia levels, in excess of the normal rate of hepatic clearance, especially in advanced stages of the disease.14

The most frequent subtype of immunoglobulin produced by multiple myeloma seems to be IgG, followed by IgA.4 Our patient had a subtype of IgG and was in an advanced stage of the disease, with very high levels of ammonia (151μmol/L); these findings agree with those reported in the literature.4,5

Early diagnosis is essential since prognosis in these patients is poor, and the condition may even be fatal without proper treatment.4

In the most comprehensive study to date including patients with acute encephalopathy and triphasic waves, aetiology was found not to affect prognosis; absent EEG background reactivity, on the other hand, did predict a poor outcome,11 as in our case, although the study did not include patients with hyperammonaemia secondary to myeloma. The role of EEG in these patients is therefore uncertain, although in our case it guided us to perform a metabolic study.

Non-hepatic hyperammonaemia should be considered a potential cause of diffuse encephalopathy in patients with multiple myeloma and exhibiting generalised triphasic waves on EEG, and it requires a different treatment approach.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: López-Blanco R, de Fuenmayor-Fernández de la Hoz CP, González de la Aleja J, Martínez-Sánchez P, Ruiz-Morales J. Encefalopatía hiperamoniémica en relación con mieloma múltiple. Neurología. 2017;32:339–341.