In the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the neurological complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection and their pathophysiology are being identified.1–4 We present a case of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) appearing as a manifestation of COVID-19.

Our patient is a 54-year-old woman with history of arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obesity, obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, polycystic liver and kidney disease and stage 3b chronic kidney disease, and anterior cervical spondylosis due to disc herniation. She visited the emergency department due to a 4-day history of paraesthesia initially manifesting in the fingertips and subsequently in the tips of the toes, progressively associated with distal weakness. She also reported low-grade fever and vomiting of simultaneous onset, and no diarrhoea or respiratory symptoms.

The neurological examination revealed severe distal weakness in the left hand (0/5 in the extensor digitorum and carpal extensor muscles, 2/5 in the flexor digitorum and carpal flexor muscles, and 2/5 in the interosseous muscles) and mild weakness in the right hand (4/5 in the extensor digitorum and carpal extensor muscles and 4/5 in the interosseous muscles); mild weakness was also observed in the left foot (4/5 in the tibialis anterior, lateral peroneus, and tibialis posterior muscles) as well as dysaesthesia in the tips of the toes and Achilles tendon areflexia.

A lumbar puncture revealed albuminocytologic dissociation; considering the clinical diagnosis of GBS with sensorimotor involvement, we started treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins. Foot weakness worsened during the first 24 hours (3/5 in the tibialis anterior, lateral peroneus, and tibialis posterior muscles bilaterally) but subsequently showed a progressive improvement, with complete resolution at 10 days and only residual dysaesthesia persisting in the tips of the toes.

Given the epidemiological context, SARS-CoV-2 is considered a possible trigger of GBS; a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of nasopharyngeal exudate was conducted, yielding negative results. During the course of the symptoms, the patient presented fever, and vomiting persisted, as well as an alveolar infiltrate in the right lower and middle lobes in a chest radiography, with negative results in urine pneumococcal antigen and Legionella antigen tests. Blood analysis results revealed lymphocytopaenia, as well as elevated levels of D-dimer, ferritin, and lactate dehydrogenase. A second PCR test for SARS-CoV-2, performed at 24 hours, yielded positive results; therefore, we started empirical treatment with ceftriaxone, azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine, and lopinavir/ritonavir.

At day 6 after admission, the patient presented rapidly progressive severe respiratory insufficiency due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), requiring non-invasive ventilatory support with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). An additional chest radiography revealed bilateral alveolar opacities. Given the clinical and radiological progression, we decided to administer treatment with methylprednisolone and tocilizumab.

Finally, the patient’s respiratory symptoms progressively improved, and we were able to suspend ventilatory support and subsequently oxygen therapy. The patient was discharged 15 days after admission, with no vomiting or neurological symptoms.

In the aetiology study, the autoimmunity study yielded negative results for ANA, ANCA, RF, anti-dsDNA, and antigangliosides and positive results for anti-Ro antibodies; serology studies for cytomegalovirus, Borrelia, Campylobacter, Mycoplasma, HIV, and syphilis all returned negative results. Cerebrospinal fluid PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 yielded negative results. An electrophysiological study performed 2 months later showed decreased amplitude of sensory potentials in all 4 limbs and, to a lesser degree, decreased motor evoked potential amplitudes; an electromyography using coaxial needle electrodes showed a slightly neurogenic recruitment pattern in distal muscles of the lower limbs, with no signs of denervation. Results were compatible with the acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) subtype of GBS, in the recovery phase.

GBS is a paradigmatic post-infectious inflammatory disease, with a known association with such viral infections as influenza, cytomegalovirus, or Epstein-Barr virus; more recently, it has been associated with emerging viruses, such as Zika, dengue, or chikungunya. Other cases have been reported in association with other coronaviruses, such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus.4,5

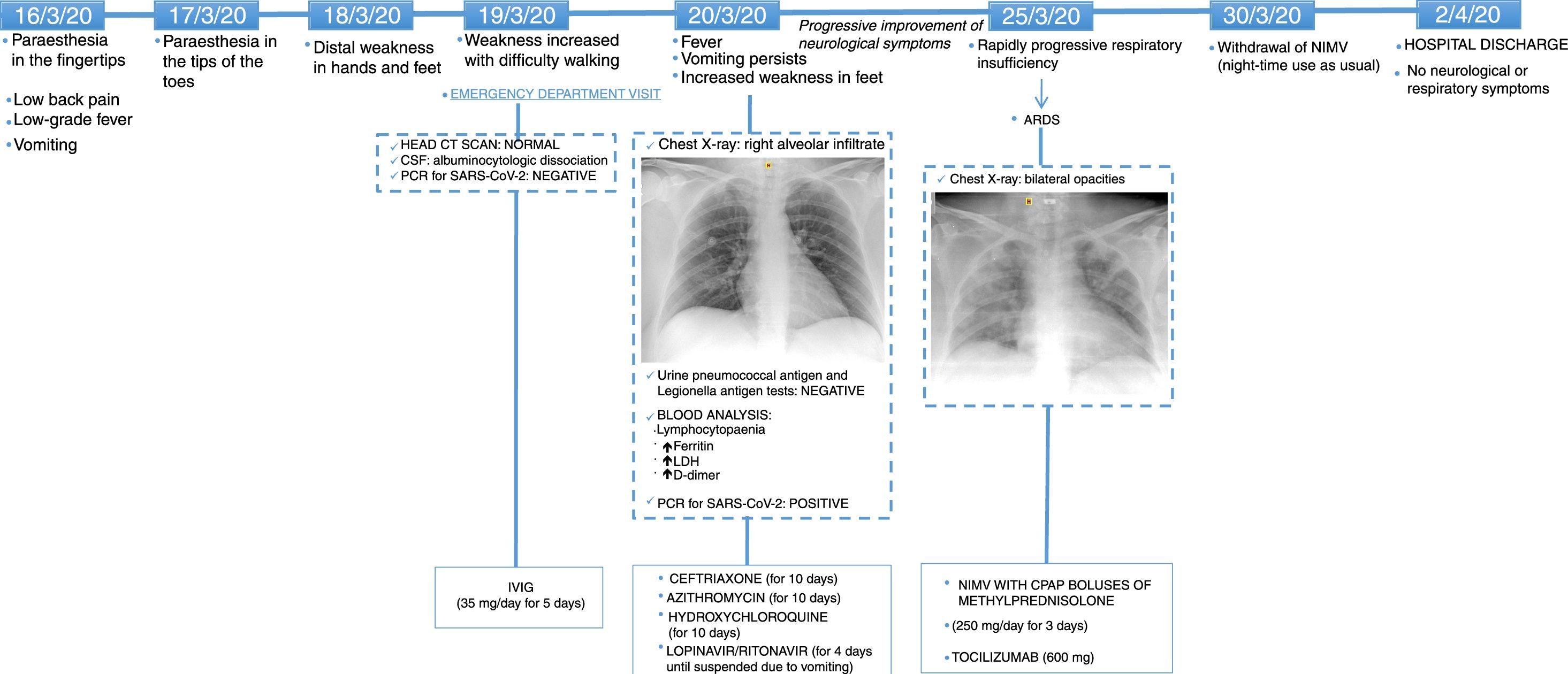

In general, the timeline of this case (Fig. 1) suggests that the patient presented an initial phase of viral replication, with respiratory involvement manifesting as pneumonia, digestive system involvement manifesting as persistent vomiting, and neurological involvement manifesting as axonal sensorimotor neuropathy. She later presented an inflammatory phase with ARDS.

Timeline of symptom onset, complementary tests, treatments administered, and clinical progression.

ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; CT: computed tomography; IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulins; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; NIMV: non-invasive mechanical ventilation; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

Several cases of GBS have been reported in association with COVID-194,6; however, the pathogenic mechanism remains unknown. In most cases, viral symptoms manifest before neurological symptoms, in line with the post-infectious paradigm.6–9 In some cases,10–13 as in our patient, both types of symptoms overlap, suggesting a possible parainfectious mechanism.

In the current epidemiological context, a high level of suspicion of infection with SARS-CoV-2 should be maintained in all cases of GBS, since systemic symptoms may have an even greater role than neurological signs in the prognosis of these patients.