Mixed dementia (DMix) refers to dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease in addition to cerebrovascular disease. The study objectives were to determine the clinical and imaging factors associated with Dmix and compare them to those associated with Alzheimer disease.

Material and methodsCross-sectional study including 225 subjects aged 65 years and over from a memory clinic in a tertiary hospital in Mexico City. All patients underwent clinical, neuropsychological, and brain imaging studies. We included patients diagnosed with DMix or Alzheimer disease (AD). A multivariate analysis was used to determine factors associated with DMix.

ResultsWe studied 137 subjects diagnosed with Dmix. Compared to patients with AD, Dmix patients were older and more likely to present diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and history of cerebrovascular disease (P<.05). The multivariate analysis showed that hypertension (OR 1.92, CI 1.62-28.82; P=.009), white matter disease (OR 3.61, CI 8.55-159.80; P<.001), and lacunar infarcts (OR 3.35, CI 1.97-412.34; P=.014) were associated with Dmix, whereas a history of successfully treated depression showed an inverse association (OR 0.11, CI 0.02-0.47; P=0.004)

ConclusionsDMix may be more frequent than AD. Risk factors such as advanced age and other potentially modifiable factors were associated with this type of dementia. Clinicians should understand and be able to define Dmix.

El concepto de demencia mixta (DMix) se refiere a la demencia por enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) y la presencia de enfermedad vascular cerebral (EVC). El objetivo del estudio fue identificar los factores clínicos e imagenológicos asociados a la DMix en comparación con la enfermedad de Alzheimer.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal que incluyó a 225 sujetos de 65 años y más, en la clínica de memoria de un hospital de tercer nivel de la Ciudad de México. A todos los pacientes se les realizó una evaluación clínica, neuropsicológica y una imagen cerebral. Se incluyó a pacientes con diagnóstico de DMix y EA. Se realizó un análisis multivariado para determinar factores de asociación a la DMix.

ResultadosSe estudió a 137 sujetos con DMix. En comparación con los pacientes con EA, en los pacientes con DMix los factores asociados fueron mayor edad, diabetes, hipertensión y dislipidemia, así como antecedente de EVC, p<0,05. El análisis multivariado mostró que la hipertensión (OR 1,92, IC: 1,.62-28.82, p<0,05), la enfermedad de sustancia blanca (OR 3,61, IC: 8,55-159,80, p<0,05) e infartos lacunares (OR 3,35, IC: 1,97-412,34, p<0,05) estuvieron asociados a la DMix, mientras que la historia de depresión resuelta tuvo una asociación inversa (OR 0,11, IC: 0,02-0,47, p<0,05).

ConclusionesLa DMix podría ser más frecuente que la EA. Factores de riesgo como la edad avanzada y otros potencialmente modificables se relacionaron con esta forma de demencia. Es necesario conocer y definir a la DMix.

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the world's leading cause of dementia, accounting for 50% to 56% of all cases. AD combined with cerebrovascular disease (CVD) has been called mixed dementia (MD) and has both cortical and subcortical components; it represents 13% to 17% of all dementia cases worldwide.1 Both AD and vascular cognitive impairment are directly associated with age.2

According to a review article of epidemiological studies, the estimated prevalence of MD is between 20% and 40%.3 In a study analysing the autopsies of a series of patients with dementia, 38% of the patients with AD displayed lacunar infarcts.4 Co-presence of other diseases in elderly patients plays a major role in the pathogenesis of dementia, and this implies that there will be fewer cases of ‘pure’ forms of dementia in the future. Some studies have shown that degeneration combined with cardiovascular risk factors constitutes the most frequent cause of cognitive impairment in the elderly.2,5

Other researchers have used the term MD to refer to combinations of at least 2 types of dementia (AD, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, etc.). According to the most widely accepted definition, MD combines histopathologically confirmed features of AD (senile plaques due to amyloid beta deposition) and cerebrovascular lesions of ischaemic and/or haemorrhagic origin. However, diagnosing this entity and distinguishing it from other conditions remains controversial.6

From a clinical viewpoint, loss of memory (especially episodic and semantic) is considered a typical feature of AD, whereas executive dysfunction has traditionally been associated with vascular cognitive impairment. For this reason, a joint statement by the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association recommends performing a complete neuropsychological assessment with specific tests of different cognitive domains to determine which cognitive functions are impaired and identify the type of dementia.7 However, the cognitive profile of MD has not been precisely defined. In addition, the literature on MD remains limited; no consensus documents or diagnostic criteria have been published to date. The purpose of our study was to identify clinical and imaging factors associated with DM that may help differentiate this condition from AD.

MethodsThis retrospective study was conducted between January 2010 and September 2014. We gathered data from a memory clinic in a tertiary referral hospital in Mexico City which provides care to patients referred by other specialists due to memory problems. We included all patients diagnosed with either AD or MD. Probable AD was diagnosed by a neurologist and/or a geriatrician based on the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria.8 MD was diagnosed when patients met criteria for possible AD8 with imaging studies pointing to vascular disease (small or large vessel disease) and evidence of both cortical and subcortical dysfunction on neuropsychological tests. The neuropsychologist assessing patients’ cognitive profiles was an expert in diagnosing both conditions.

We excluded patients with other types of dementia, those whose assessment was incomplete, patients with depression or other psychiatric disorders, and those with uncompensated metabolic disorders.

Neuropsychological function was assessed on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),9 the clock-drawing test,10 semantic fluency test (temporal lobe function), and phonemic fluency test (frontal lobe function). We also evaluated the number of intrusion and perseveration errors. Patients also completed the 5-word test, an evaluation of verbal episodic memory based on free and cued recall of a list of 5 words and intended to identify alterations in any of the phases of episodic memory (encoding, storage, and retrieval),11,12 as well as the Frontal Assessment Battery.13

Function was assessed on the Katz index of independence in activities of daily living14 (feeding, dressing, continence, toileting, bathing, transferring) and the Lawton instrumental activities of daily living scale15 (ability to handle finances, shopping, mode of transportation, laundry, food preparation, housekeeping, ability to use telephone, and responsibility for own medications). Inability to perform at least one basic daily living activity and/or one instrumental activity due to cognitive impairment supported the diagnosis of dementia. Sociodemographic characteristics and risk factors were obtained from medical records. We included the following data to describe our sample: sex; age; level of education and total years of schooling; presence/absence of arterial hypertension (AHT), diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, CVD, and heart disease; and history of depression and alcohol or tobacco use documented and/or diagnosed by a geriatrician. We also gathered data on serum levels of vitamin B12 and folic acid, using reference values from the laboratory corresponding to the centre where analyses were conducted to establish an abnormal cut-off point.

An independent neurologist viewed the patients’ brain CT and/or 1.5T MR images and used standard neuroimaging terminology for small and large vessel disease to define imaging features (atrophy, leukoencephalopathy, lacunar infarcts, CVD, etc.).16

Statistical analysisClinical and imaging differences in our sample were analysed with parametric and non-parametric descriptive statistics. We used the chi-square test for categorical variables and the t test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were subsequently applied to identify factors associated with MD; patients diagnosed with AD constituted the reference group. Significance was set at P<.05. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Our study was approved by the ethics committee at our centre.

ResultsWe included 225 patients: 88 with AD (39%) and 137 with MD (61%). The mean age of our sample was 82.9±6.83 years. Women accounted for 52% of the total. Mean years of schooling were 9.5±6.33.

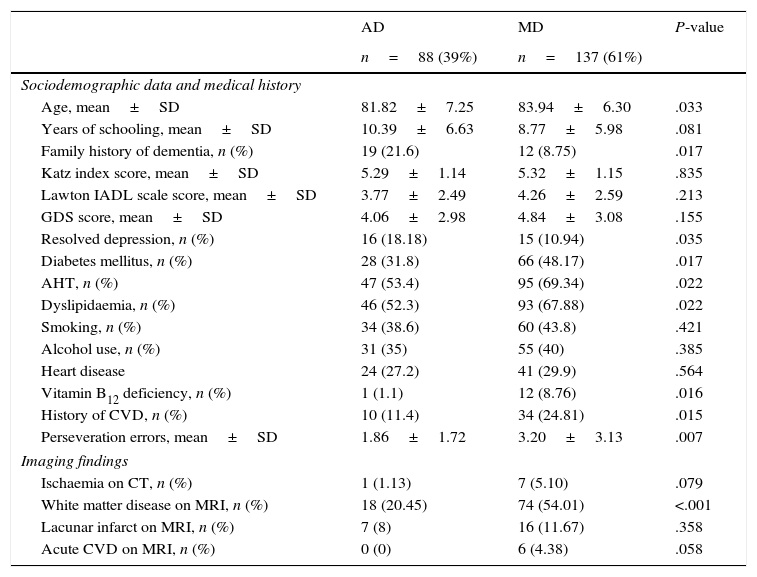

Table 1 compares sociodemographic, health-related, imaging, and cognitive characteristics in our sample. Patients with MD were older than those with AD (P=.033) and showed higher frequencies of diabetes mellitus (48%; P=.017), AHT (69%; P=.022), dyslipidaemia (68%; P=.022), vitamin B12 deficiency (9%; P=.016), and history of CVD (25%; P=.015). In contrast, patients in this group were less likely to have a family history of dementia (9%; P=.017) or history of depression (11%; P=.035).

Sociodemographic, health-related, psychometric, and imaging characteristics of our sample.

| AD | MD | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=88 (39%) | n=137 (61%) | ||

| Sociodemographic data and medical history | |||

| Age, mean±SD | 81.82±7.25 | 83.94±6.30 | .033 |

| Years of schooling, mean±SD | 10.39±6.63 | 8.77±5.98 | .081 |

| Family history of dementia, n (%) | 19 (21.6) | 12 (8.75) | .017 |

| Katz index score, mean±SD | 5.29±1.14 | 5.32±1.15 | .835 |

| Lawton IADL scale score, mean±SD | 3.77±2.49 | 4.26±2.59 | .213 |

| GDS score, mean±SD | 4.06±2.98 | 4.84±3.08 | .155 |

| Resolved depression, n (%) | 16 (18.18) | 15 (10.94) | .035 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 28 (31.8) | 66 (48.17) | .017 |

| AHT, n (%) | 47 (53.4) | 95 (69.34) | .022 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 46 (52.3) | 93 (67.88) | .022 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 34 (38.6) | 60 (43.8) | .421 |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | 31 (35) | 55 (40) | .385 |

| Heart disease | 24 (27.2) | 41 (29.9) | .564 |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | 12 (8.76) | .016 |

| History of CVD, n (%) | 10 (11.4) | 34 (24.81) | .015 |

| Perseveration errors, mean±SD | 1.86±1.72 | 3.20±3.13 | .007 |

| Imaging findings | |||

| Ischaemia on CT, n (%) | 1 (1.13) | 7 (5.10) | .079 |

| White matter disease on MRI, n (%) | 18 (20.45) | 74 (54.01) | <.001 |

| Lacunar infarct on MRI, n (%) | 7 (8) | 16 (11.67) | .358 |

| Acute CVD on MRI, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (4.38) | .058 |

AD: Alzheimer disease; CVD: cerebrovascular disease; SD: standard deviation; MD: mixed dementia; AHT: arterial hypertension; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CT: computed tomography.

Regarding neuroimaging findings, patients with MD showed more signs of ischaemic stroke (P=.079) and of white matter disease (P<.001).

According to neurocognitive test results, patients with MD tended to make more perseveration errors than those with AD (3.2 vs 1.86; P=.007).

No significant intergroup differences were found regarding sociodemographic characteristics and other risk factors (sex, level of education, marital status, history of tobacco or alcohol dependency, history of cardiovascular disease).

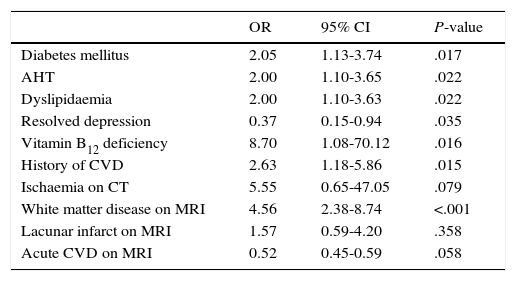

The following factors were found to be associated with MD in the univariate analysis: vitamin B12 deficiency (OR 8.7; 95% CI, 1.08-70.12; P=.016), white matter disease (OR 4.56; 95% CI, 2.38-8.74; P<.001), history of CVD (OR 2.63; 95% CI, 1.18-5.86; P=.015), diabetes mellitus (OR 2.05; 95% CI, 1.13-3.74; P=.017), AHT (OR 2.00; 95% CI, 1.10-3.65; P=.022), and dyslipidaemia (OR 2.00; 95% CI, 1.10-3.63; P=.022) (Table 2). Depression was inversely correlated with MD (OR 0.37; 95% CI, 0.15-0.94; P=.035).

Factors associated with MD. Univariate analysis.

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.05 | 1.13-3.74 | .017 |

| AHT | 2.00 | 1.10-3.65 | .022 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 2.00 | 1.10-3.63 | .022 |

| Resolved depression | 0.37 | 0.15-0.94 | .035 |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency | 8.70 | 1.08-70.12 | .016 |

| History of CVD | 2.63 | 1.18-5.86 | .015 |

| Ischaemia on CT | 5.55 | 0.65-47.05 | .079 |

| White matter disease on MRI | 4.56 | 2.38-8.74 | <.001 |

| Lacunar infarct on MRI | 1.57 | 0.59-4.20 | .358 |

| Acute CVD on MRI | 0.52 | 0.45-0.59 | .058 |

AD: Alzheimer disease; CVD: cerebrovascular disease; SD: standard deviation; MD: mixed dementia; AHT: arterial hypertension; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CT: computed tomography.

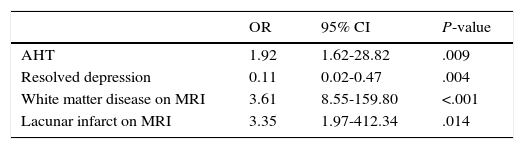

Table 3 displays the multivariate logistic regression analysis in which AHT (OR 1.92; 95% CI, 1.62-28.82; P=.009), white matter disease on MRI (OR 3.61; 95% CI, 8.55-159.80; P<.001), and lacunar infarction on MRI (OR 3.35; 95% CI, 1.97-412.34; P=.014) continued to be associated with MD. History of depression was inversely correlated with MD, that is, patients with a history of resolved depression were less likely to present MD (OR 0.11; 95% CI, 0.02-0.47; P=.004).

Logistic regression analysis.

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AHT | 1.92 | 1.62-28.82 | .009 |

| Resolved depression | 0.11 | 0.02-0.47 | .004 |

| White matter disease on MRI | 3.61 | 8.55-159.80 | <.001 |

| Lacunar infarct on MRI | 3.35 | 1.97-412.34 | .014 |

CVD: cerebrovascular disease; AHT: arterial hypertension; CI: confidence interval; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; OR: odds ratio.

MD was the most frequent form of dementia in our sample (60%), with patients with AD accounting for 40% of the total. Our results are in line with the literature; according to published autopsy studies, prevalence of MD ranges from 2% to 58% and is more frequent in the elderly (mainly patients over 80).6 The Honolulu-Asia Ageing Study,5 which included results from 363 autopsies, found a weak correlation between clinical and neuropathological diagnoses of dementia. Although 56% of the patients had been diagnosed with possible or probable AD, only 19% showed compatible autopsy findings. In contrast, the number of patients diagnosed with MD in life increased considerably after autopsies (16% vs 40%).

Mean age in our study was 82.95 years; elderly patients are obviously more likely to experience multiple diseases that may promote dementia. According to our analysis, patients with MD were older, and the difference was statistically significant. In a study by James et al.,17 DM was more frequent in individuals older than 90 whereas AD was more prevalent in younger individuals. These researchers hypothesised that clinical expression of AD is attenuated in advanced age due to the presence of multiple disorders, especially cardiovascular diseases. Our study found an association between MD and vascular risk factors, which suggests that vascular factors may be involved in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment. Diabetes mellitus, AHT, dyslipidaemia, and history of CVD were more frequent among patients with MD; out of all risk factors, AHT displayed the strongest association. Unverzagt et al.18 conducted a prospective study including over 23000 patients to analyse the association between cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive impairment; here, only elevated systolic blood pressure was found to be correlated with cognitive impairment. Shah et al.19 demonstrated the association between history of AHT in adulthood and plasma amyloid beta concentrations; in this study, high blood pressure was found to be correlated with low plasma levels of Aβ42 and findings of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in postmortem studies. Jellinger et al.20 performed over 1100 autopsies of patients with dementia and such chronic diseases or vascular risk factors as CVD, heart failure, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, AHT, and dyslipidaemia. These researchers observed an association between vascular risk factors and amyloid-β pathology, neurofibrillary pathology, cerebral small-vessel disease, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and even α-synuclein deposition, especially in very elderly patients.

Interestingly, our study found an association between MD and history of vitamin B12 deficiency in the univariate analysis. Neurological disorders associated with vitamin B12 deficiency tend to affect patients aged 40 to 90; incidence peaks between ages 60 and 70.21 Diabetes mellitus has been reported as a cause of functional B12 deficiency in elderly diabetic patients22 as in treatment with metformin.23 Age is another risk factor for vitamin B12 deficiency.24 Advanced age and the high incidence of diabetes mellitus in our sample of patients with MD (48%) may explain these results. Further longitudinal studies should be conducted to confirm the association between vitamin B12 deficiency, AD, and MD.25

History of late-onset or refractory depression constitutes a risk factor for dementia. Taylor et al.26 have described an association between depression and cognitive impairment. According to these researchers, this association is stronger in the elderly due to the presence of multiple cardiovascular risk factors, leading to what is known as vascular depression. Vascular depression is more frequent among elderly patients and more long-lasting than non-vascular depression. It is characterised by poor response to pharmacological treatment, greater risk of recurrence, and cognitive impairment, especially executive dysfunction. CVD is believed to promote or trigger symptoms of depression. Our study supports this hypothesis: according to our results, a history of resolved depression seemed to protect against MD.26

Furthermore, patients with MD made a greater number of perseveration errors on neuropsychological tests. Semantic and phonemic verbal fluency primarily reflect memory and executive function. Semantic fluency, also called category fluency, evaluates temporal lobe function, whereas phonemic fluency assesses both frontal and temporal lobe function, given that patients must refrain from using certain words (proper names, numbers, etc.), a task also involving working memory. Although both semantic and phonemic fluency are impaired in AD, the latter is considerably more impaired in these patients.27,28 Intrusion errors are normally associated with semantic and memory impairment and therefore help assess temporal lobe function. Perseveration errors, in contrast, are typically associated with problems with self-monitoring, working memory, and executive function (frontal and subcortical circuits).29,30 Patients in our study made both types of errors, although perseveration errors were considerably more frequent among patients with MD. This may indicate that cognitive impairment in these patients arises from multiple aetiologies.

Imaging findings were clearly different between groups: patients with MD displayed small and large vessel disease (especially lacunar infarcts). Brain MRI evidence of white matter lesions was 3 times more frequent in patients with MD than in those with AD. White matter disease, appearing as hyperintensities in T2-weighted and FLAIR MRI sequences, has been linked to cognitive impairment and depression. Likewise, it is more frequent in patients with such other conditions as diabetes mellitus, AHT, atherosclerosis, and tobacco use, but it also appears in elderly individuals with no comorbidities.31

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the study population was drawn from a tertiary referral hospital and presented multiple comorbidities, which may explain the high number of cases with MD. Furthermore, the sample size was small and did not use validated Spanish-language neuropsychological tests; likewise, histology studies and biomarkers might have provided valuable additional data. Its cross-sectional design limits our ability to establish casual associations between risk factors and dementia.

However, our study also has several strengths. In contrast with other types of dementia, MD has only been addressed by a few studies. To our knowledge no other studies of this entity have been conducted in the Mexican population. Anticipating more detailed future studies, our findings provide preliminary data on the characteristics of MD and the role of potentially modifiable risk factors.

ConclusionsMixed dementia is a frequent cause of cognitive impairment. Increased life expectancy and presence of comorbidities in elderly individuals pose major challenges for healthcare systems worldwide. Populations with a higher degree of cardiovascular risk are more likely to include cognitive impairment profiles with a mixed aetiology. This is relevant in that correctly identifying these potentially modifiable risk factors may result in multiple approaches to treating MD. Future studies should aim to define the concept and clinical characteristics of MD and establish the most appropriate diagnostic tools and protocols.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Moreno Cervantes C, Mimenza Alvarado A, Aguilar Navarro S, Alvarado Ávila P, Gutiérrez Gutiérrez L, Juárez Arellano S, et al. Factores asociados a la demencia mixta en comparación con demencia tipo Alzheimer en adultos mayores mexicanos. Neurología. 2017;32:309–315.