Patients presenting sequelae of poliomyelitis may present new symptoms, known as post-polio syndrome (PPS).

ObjectiveTo identify the clinical and functional profile and epidemiological characteristics of patients presenting PPS.

Patients and methodsWe performed a retrospective study of 400 patients with poliomyelitis attended at the Institut Guttmann outpatient clinic, of whom 310 were diagnosed with PPS. We describe patients’ epidemiological, clinical, and electromyographic variables and analyse the relationships between age of poliomyelitis onset and severity of the disease, and between sex, age of PPS onset, and the frequency of symptoms.

ResultsPPS was more frequent in women (57.7%). The mean age at symptom onset was 52.4 years, and was earlier in women. Age at primary infection > 2 years was not related to greater poliomyelitis severity.

The frequency of symptoms was: pain in 85% of patients, loss of strength in 40%, fatigue in 65.5%, tiredness in 57.8%, cold intolerance in 20.2%, dysphagia in 11.7%, cognitive complaints in 9%, and depressive symptoms in 31.5%. Fatigue, tiredness, depression, and cognitive complaints were significantly more frequent in women.

Fifty-nine percent of patients presented electromyographic findings suggestive of PPS.

ConclusionsWhile the symptoms observed in our sample are similar to those reported in the literature, the frequencies observed are not. We believe that patients’ clinical profile may be very diverse, giving more weight to such objective parameters as worsening of symptoms or appearance of weakness; analysis of biomarkers may bring us closer to an accurate diagnosis.

Las personas con secuelas de poliomielitis pueden presentar nuevos síntomas que constituirían el síndrome pospolio (SPP).

ObjetivoIdentificar el perfil clínico y funcional, y las características epidemiológicas de personas que padecen SPP.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de 400 pacientes afectados de poliomielitis visitados en consulta externa del Institut Guttmann, de los cuales a 310 se les diagnosticó SPP. Se describieron variables epidemiológicas, clínicas y electromiográficas. Se analizó la relación entre edad de adquisición de la polio y gravedad de la misma, así como entre el sexo y la edad de aparición del SPP y la frecuencia de síntomas.

ResultadosSe observó mayor frecuencia de SPP en mujeres (57,7%). La edad media de inicio de la clínica fue 52,4 años, más precoz en mujeres. Edad de primoinfección mayor de 2 años no se relacionó con mayor gravedad de la polio.

La frecuencia de síntomas fue: dolor 85%, pérdida de fuerza 40%, fatiga 65,5%, cansancio 57,8%, intolerancia al frío 20,2%, disfagia 11,7%, quejas cognitivas 9%, síntomas depresivos 31,5%. La fatiga, el cansancio, la depresión y las quejas cognitivas fueron significativamente más frecuentes en mujeres.

El 59% de los pacientes presentaban hallazgos electromiográficos sugestivos de SPP.

ConclusionesEl tipo de sintomatología que presentaba nuestra muestra es similar a la publicada, no así en la frecuencia de la misma. Creemos que el perfil clínico de los pacientes podría ser muy diverso, y dar mayor peso a parámetros objetivos como el empeoramiento o la aparición de debilidad y el estudio de biomarcadores podría acercarnos más a un diagnóstico preciso.

Poliomyelitis is caused by infection with an enterovirus that attacks motor neurons, mainly those in the spinal cord.1 Millions of people worldwide present physical sequelae of poliomyelitis, resulting in varying levels of disability.

Humans are the reservoir of the virus; person-to-person transmission typically occurs via the faecal-oral route. Most cases occur in children younger than 5 years and during summer. Patients initially present fever, fatigue, headache, vomiting, and rigidity, with loss of strength presenting within hours. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one in every 200 infected individuals presents some form of irreversible paralysis, and 5%-10% of patients die due to respiratory failure.2 With the development of polio vaccines (first the Salk vaccine, delivered by injection, in 1955, and subsequently the oral vaccine developed by Sabin in 1963), mass vaccination campaigns successfully controlled the spread of the virus. The WHO certified the eradication of poliomyelitis in Western countries after the last case was reported in America in 1994, in the Pacific in 2000, and in Europe in 2002. However, according to a 2015 WHO report, poliomyelitis continues to be endemic in Afghanistan and Pakistan.3

Until relatively recently, poliomyelitis was considered a neurologically stable disease that could leave functional sequelae after the acute phase. However, in the 1970s, cases began to be detected of new symptoms causing functional worsening in patients with history of poliomyelitis.

After the Halstead criteria for post-polio syndrome (PPS) were proposed in 1985, the WHO included the condition as a distinct entity in the ninth revision of the International Classification of Diseases,3 following protracted debate over whether symptoms were the result of a new condition or were simply explained by age-related functional decline.

Diagnosis of PPS is currently based on the March of Dimes criteria,4 a modified version of the Halstead criteria published in April 2010:

–Prior paralytic poliomyelitis with evidence of motor neuron loss, as confirmed by history of the acute paralytic illness, signs of residual weakness and atrophy of muscles on neurologic examination, and signs of denervation on electromyography (EMG).

–A period of partial or complete functional recovery after acute paralytic poliomyelitis, followed by an interval (usually 15 years or more) of stable neurologic function.

–Gradual or sudden onset of progressive and persistent new muscle weakness or abnormal muscle fatigability (decreased endurance), with or without generalised fatigue, muscle atrophy, or muscle and joint pain. Less commonly, symptoms attributed to PPS include new problems with breathing or swallowing.

–Symptoms persist for at least a year.

–Exclusion of other neurologic, medical and orthopaedic problems as causes of symptoms.

Halstead noted a marked increase in the number of articles addressing this entity between 1995 and 2000, while the number of cases attended at units specialising in PPS also peaked in the United States.5

This activity has decreased in the last decade, although patients with PPS are still alive and growing older. Poliomyelitis vaccination was conducted nearly 10 years later in Spain than in the United States and other Western countries, which has resulted in a delay in the appearance of cases of PPS and explains the increasing current interest in the condition.

The pathogenesis of PPS is not understood. One of the main hypotheses suggests decompensation between chronic denervation and the reinnervation mechanisms that help maintain muscle function. Based on muscle biopsy findings, another hypothesis suggests reactivation of latent virus in motor neurons.3

Although the risk factors for PPS are not well characterised, some studies suggest that the risk of developing PPS may increase with older age in the acute phase of the disease, female sex, greater severity of motor symptoms of poliomyelitis, lower level of functional recovery after acute infection, longer duration of the latency period between the acute phase of the disease and onset of recovery, use of mechanical ventilation in the acute phase, and high level of physical activity.6

The mean age of the primary infection in Spanish series is approximately 2 years, whereas in other developed countries it is usually older.7 The severity of the acute infection is evaluated with different methods in different studies. According to Águila-Maturana et al.,7 severity of PPS is determined by such factors as the severity of sequelae after recovery from the primary infection, need for mechanical ventilation, number of limbs affected, time needed for gait recovery, and number of interventions. Thus, older age at disease onset may be associated with more severe acute infection, leading to more severe sequelae. All these factors may increase the risk of developing PPS.

The purpose of this study was to describe the epidemiological characteristics and clinical and functional profile of a group of patients diagnosed with PPS. This information may help characterise these patients’ needs with a view to promoting healthcare strategies for reducing the functional impact of the syndrome. We also aimed to evaluate the applicability of diagnostic criteria for PPS in patients with history of poliomyelitis who visited our centre due to functional worsening.

Material and methodsPatientsWe conducted a retrospective study of patients attended at Institut Guttmann's unit for patients with poliomyelitis sequelae.

We gathered data from a random sample of 400 patients with poliomyelitis sequelae who were followed up on an outpatient basis by our centre's poliomyelitis unit. All patients diagnosed with PPS according to the March of Dimes criteria4 were eligible for inclusion.

We excluded all patients presenting signs, symptoms, and/or EMG alterations compatible with other neurological disease; patients with hypo- or hyperthyroidism, severe anaemia, or other systemic disorders that may cause symptoms similar to those of PPS; and those presenting orthopaedic conditions responsible for their symptoms.

Study variablesWe gathered the following demographic, clinical, and EMG variables:

- -

Demographic variables: sex, age at onset of primary infection, year of primary infection, incidence of poliomyelitis by decade, age at onset of symptoms suggestive of PPS, time elapsed between primary infection and onset of symptoms suggestive of PPS, employment status at diagnosis of PPS.

- -

Clinical variables: need for iron lung treatment during acute infection, number of limbs affected, walking ability at the time of consultation, need for a wheelchair or other devices, need for a new orthosis since presentation of symptoms suggestive of PPS, frequency of musculoskeletal pain, patient-reported loss of strength, fatigue, tiredness, cold intolerance, cognitive complaints, depressive symptoms, and dysphagia. We also gathered data on complications associated with PPS, including shoulder disorders, radiculopathy, and bone fractures. Data were also recorded on the severity of the acute infection; poliomyelitis was classed as “severe” if the patient had required an iron lung and/or presented 3-4 affected limbs after initial recovery, according to patient-reported data.

- -

EMG variables: we evaluated EMG results (where available) to rule out other conditions and to assess acute denervation, markedly increased jitter, and blocking suggestive of PPS.

We performed a descriptive analysis of our sample of patients with PPS. Categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations (SD).

We also evaluated whether age at onset of acute infection (younger than or older than 2 years, the mean age in our sample) affected the severity of poliomyelitis. Finally, we assessed whether sex influenced age at onset of PPS, as some authors have suggested.6

Data were tested for normal distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and variables were compared with the chi square test and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test.

ResultsSample characteristics and clinical and demographic data of acute infectionOf a total of 400 patients with history of poliomyelitis attended at our centre, 310 were diagnosed with PPS.

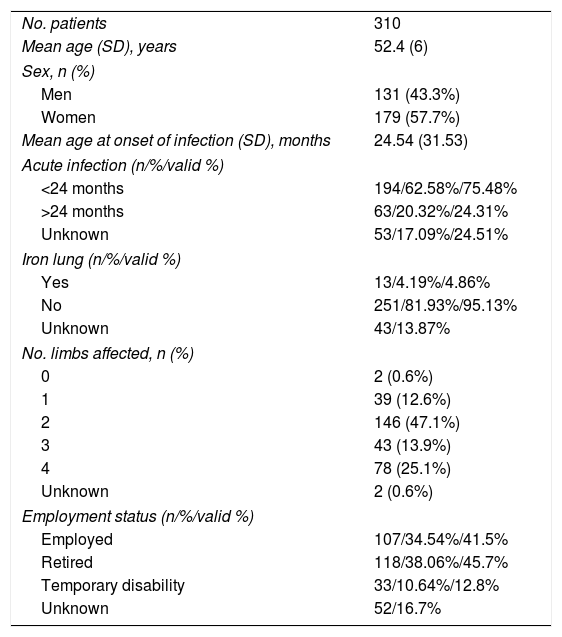

Table 1 shows the clinical and demographic characteristics of this subgroup of patients.

Characteristics of our sample of patients with diagnosis of post-polio syndrome.

| No. patients | 310 |

| Mean age (SD), years | 52.4 (6) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Men | 131 (43.3%) |

| Women | 179 (57.7%) |

| Mean age at onset of infection (SD), months | 24.54 (31.53) |

| Acute infection (n/%/valid %) | |

| <24 months | 194/62.58%/75.48% |

| >24 months | 63/20.32%/24.31% |

| Unknown | 53/17.09%/24.51% |

| Iron lung (n/%/valid %) | |

| Yes | 13/4.19%/4.86% |

| No | 251/81.93%/95.13% |

| Unknown | 43/13.87% |

| No. limbs affected, n (%) | |

| 0 | 2 (0.6%) |

| 1 | 39 (12.6%) |

| 2 | 146 (47.1%) |

| 3 | 43 (13.9%) |

| 4 | 78 (25.1%) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.6%) |

| Employment status (n/%/valid %) | |

| Employed | 107/34.54%/41.5% |

| Retired | 118/38.06%/45.7% |

| Temporary disability | 33/10.64%/12.8% |

| Unknown | 52/16.7% |

%: from patient total; PPS: post-polio syndrome; valid %: from all patients with data available.

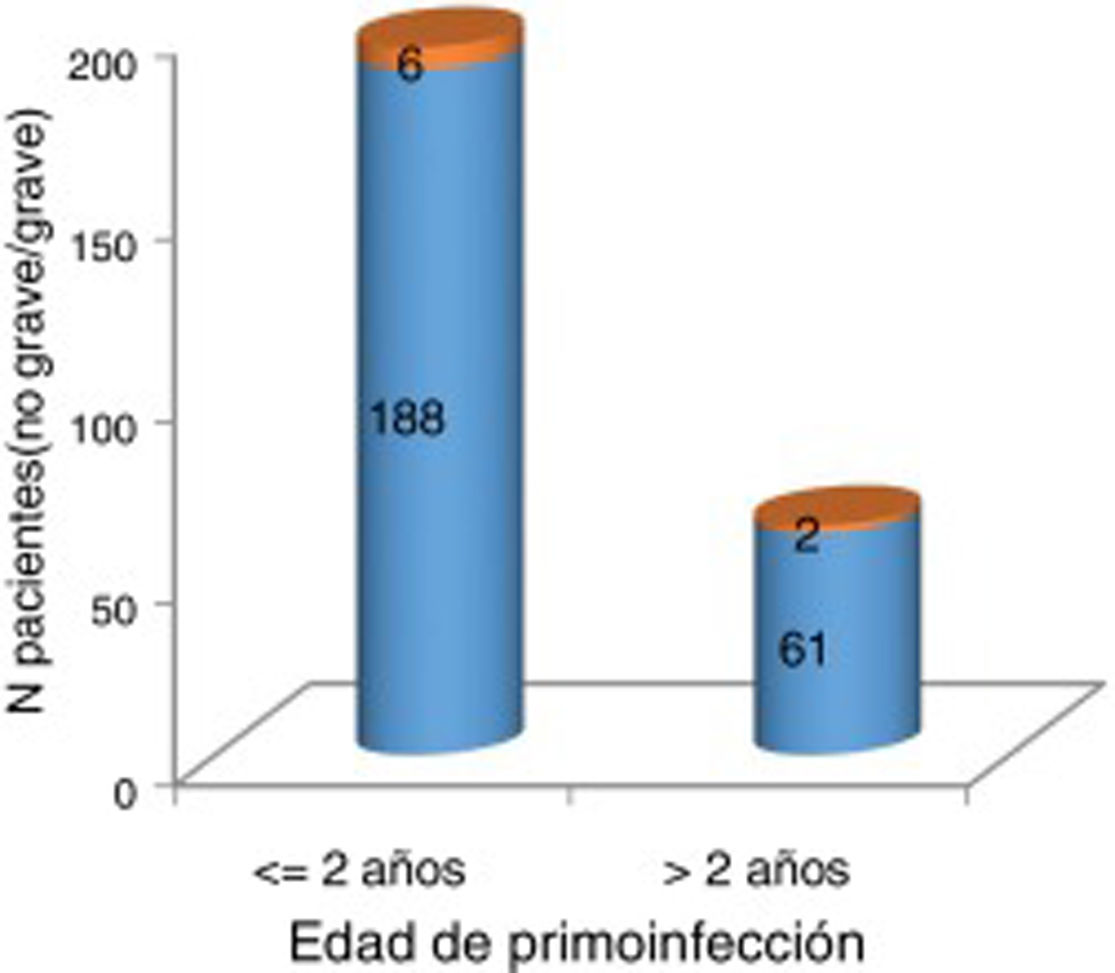

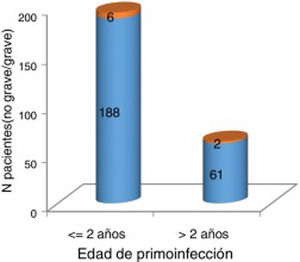

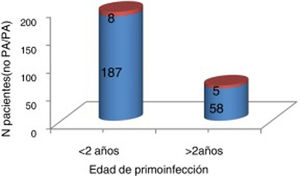

At the time of data collection, our sample had a mean age of 55 years, and included more women than men. Patients with 2 affected limbs (50%) were the largest subgroup, although 25% presented involvement of all 4 limbs. Three-quarters of patients had presented poliomyelitis before the age of 2 years. According to our analysis, patients presenting poliomyelitis after the age of 2 years did not present more severe neurological symptoms (Fig. 1).

Severity of acute poliomyelitis by age at onset of the infection (younger or older than 2 years).

Orange: severe (need for iron lung treatment and/or 3-4 affected limbs). Blue: not severe (no need for iron lung treatment and 1-2 affected limbs). No significant association was observed between older age at onset of acute poliomyelitis and greater severity of neurological symptoms (P=1).

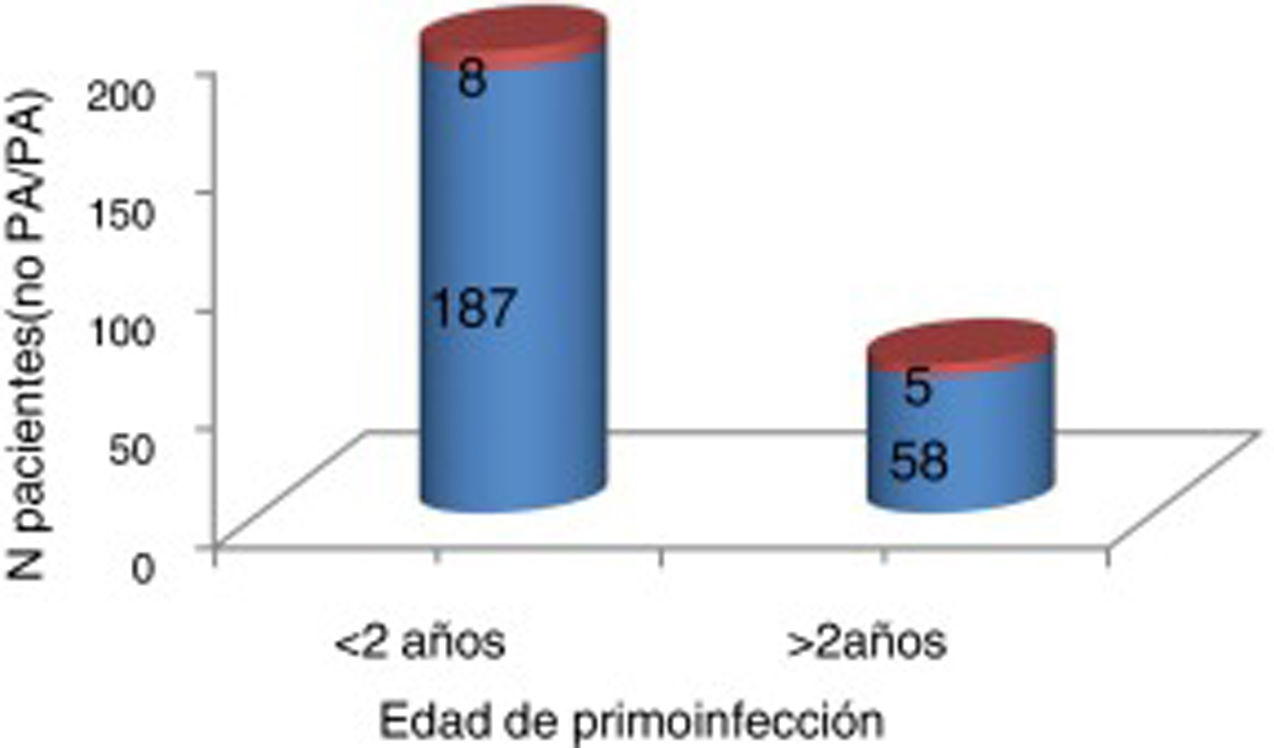

We found no significant differences in the number of patients treated with an iron lung according to age at primary infection (Fig. 2).

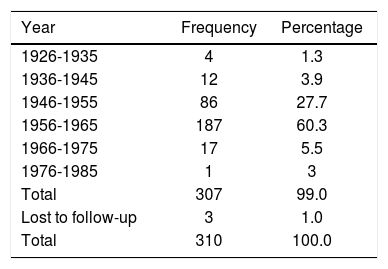

The majority of cases of poliomyelitis in our sample occurred between 1956 and 1965. The incidence of acute poliomyelitis by year is presented in Table 2.

Age of onset and patient characteristics at the time of diagnosis of post-polio syndromeSymptoms suggestive of PPS appeared at a mean age (SD) of 52.44 years (7.08).

Mean age at onset of the primary infection was 24.54 months (31.53), and the mean time from onset of acute poliomyelitis to onset of PPS was 49.94 years.

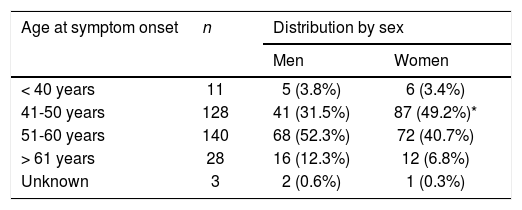

Most patients presented symptoms suggestive of PPS between the ages of 40 and 60 years, particularly between 50 and 60 years of age. Women presented symptoms at a significantly younger age than men, between ages 40 and 50 years (Table 3).

Age at onset of symptoms of post-polio syndrome, by sex.

| Age at symptom onset | n | Distribution by sex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||

| < 40 years | 11 | 5 (3.8%) | 6 (3.4%) |

| 41-50 years | 128 | 41 (31.5%) | 87 (49.2%)* |

| 51-60 years | 140 | 68 (52.3%) | 72 (40.7%) |

| > 61 years | 28 | 16 (12.3%) | 12 (6.8%) |

| Unknown | 3 | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.3%) |

*Symptom onset between the ages of 41 and 50 years was significantly more frequent among women.

(P=.01).

At the time of diagnosis of PPS, 26.1% of patients (n=81) were unable to walk. Among the 73.9% of patients (n=229) who were able to walk, 16.1% (n=50) used one orthosis and 20.3% (n=63) used 2.

At the time of diagnosis, 46.4% of patients (n=144), regardless of walking ability, required a wheelchair, and 14% needed an electric wheelchair.

After diagnosis of PPS, 24% of the patients needed an additional orthosis due to functional worsening.

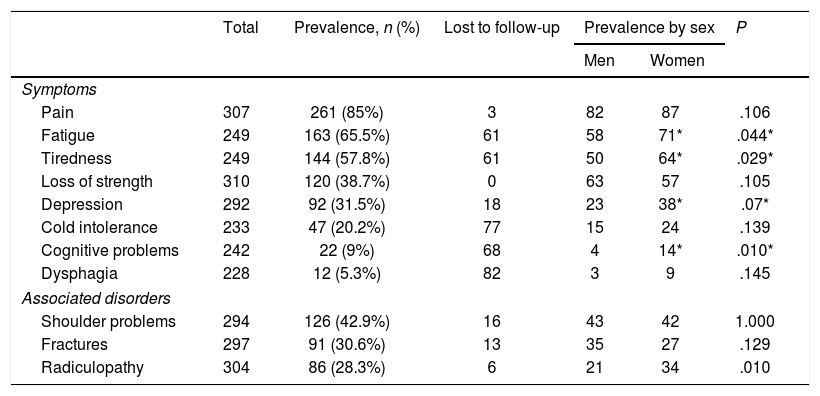

Symptoms and symptom frequencyTable 4 presents the frequency of symptoms of PPS and associated comorbidities in our sample.

Frequency of symptoms of post-polio syndrome and associated disorders.

| Total | Prevalence, n (%) | Lost to follow-up | Prevalence by sex | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||||

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Pain | 307 | 261 (85%) | 3 | 82 | 87 | .106 |

| Fatigue | 249 | 163 (65.5%) | 61 | 58 | 71* | .044* |

| Tiredness | 249 | 144 (57.8%) | 61 | 50 | 64* | .029* |

| Loss of strength | 310 | 120 (38.7%) | 0 | 63 | 57 | .105 |

| Depression | 292 | 92 (31.5%) | 18 | 23 | 38* | .07* |

| Cold intolerance | 233 | 47 (20.2%) | 77 | 15 | 24 | .139 |

| Cognitive problems | 242 | 22 (9%) | 68 | 4 | 14* | .010* |

| Dysphagia | 228 | 12 (5.3%) | 82 | 3 | 9 | .145 |

| Associated disorders | ||||||

| Shoulder problems | 294 | 126 (42.9%) | 16 | 43 | 42 | 1.000 |

| Fractures | 297 | 91 (30.6%) | 13 | 35 | 27 | .129 |

| Radiculopathy | 304 | 86 (28.3%) | 6 | 21 | 34 | .010 |

The most frequent symptom was musculoskeletal pain, followed by fatigue and tiredness. Loss of strength was reported by 40% of patients (n=120); however, this is a subjective estimation, as we did not compare the results from neurological examinations performed at different times in each patient to confirm this figure.

A total of 242 patients were asked about presence of cognitive symptoms, with 22 (9%) reporting cognitive problems. Sixteen of these had undergone a neuropsychological evaluation. In all cases, the neuropsychological evaluation revealed cognitive alterations, most frequently affecting attention (n=12), memory (n=10), cognitive processing speed (n=12), and executive function (n=8), with no accompanying depressive symptoms.

In 272 cases, clinical data were available on whether the patient presented dysphagia. Dysphagia was reported by 32 patients (11.7%); however, videofluoroscopy detected no alterations in any of these.

Women were significantly more likely to present fatigue and tiredness than men (P=.044 and P=.029, respectively), and they also presented more symptoms.

EMG was performed in 232 patients (79%), 139 of whom (59%) presented increased jitter and blocking or instability of motor unit excitability; these findings are suggestive of PPS.

No association was observed between greater severity of acute poliomyelitis and presence of EMG alterations suggestive of PPS (P=.059).

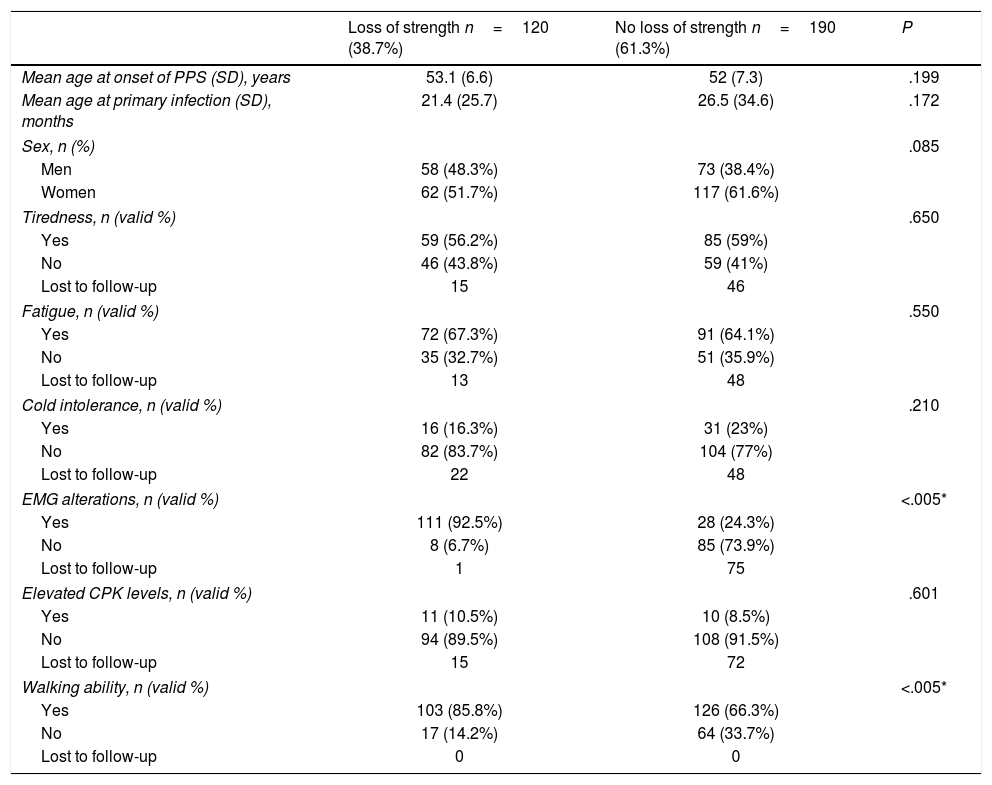

Loss of strength was reported by 38.7% of patients; given the impact of this symptom on disability and function, we evaluated the differences between patients with and without loss of strength, including demographic and clinical variables (Table 5).

Comparison between patients with and without self-reported loss of strength.

| Loss of strength n=120 (38.7%) | No loss of strength n=190 (61.3%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at onset of PPS (SD), years | 53.1 (6.6) | 52 (7.3) | .199 |

| Mean age at primary infection (SD), months | 21.4 (25.7) | 26.5 (34.6) | .172 |

| Sex, n (%) | .085 | ||

| Men | 58 (48.3%) | 73 (38.4%) | |

| Women | 62 (51.7%) | 117 (61.6%) | |

| Tiredness, n (valid %) | .650 | ||

| Yes | 59 (56.2%) | 85 (59%) | |

| No | 46 (43.8%) | 59 (41%) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 15 | 46 | |

| Fatigue, n (valid %) | .550 | ||

| Yes | 72 (67.3%) | 91 (64.1%) | |

| No | 35 (32.7%) | 51 (35.9%) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 13 | 48 | |

| Cold intolerance, n (valid %) | .210 | ||

| Yes | 16 (16.3%) | 31 (23%) | |

| No | 82 (83.7%) | 104 (77%) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 22 | 48 | |

| EMG alterations, n (valid %) | <.005* | ||

| Yes | 111 (92.5%) | 28 (24.3%) | |

| No | 8 (6.7%) | 85 (73.9%) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 1 | 75 | |

| Elevated CPK levels, n (valid %) | .601 | ||

| Yes | 11 (10.5%) | 10 (8.5%) | |

| No | 94 (89.5%) | 108 (91.5%) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 15 | 72 | |

| Walking ability, n (valid %) | <.005* | ||

| Yes | 103 (85.8%) | 126 (66.3%) | |

| No | 17 (14.2%) | 64 (33.7%) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 0 | 0 | |

CPK: creatine phosphokinase; EMG: electromyography; PPS: post-polio syndrome; SD: standard deviation; valid %: percentage of all patients with data available (excluding patients lost to follow-up).

EMG alterations: increased jitter and blocking or instability of motor unit excitability, signs of acute denervation.

Self-reported loss of strength was significantly associated with presence of EMG alterations suggestive of PPS (increased jitter and blocking or instability of motor unit excitability, signs of acute denervation) (P<.005) and with ability to walk (P<.005).

DiscussionThe main aim of our study was to describe the demographic, clinical, and neurophysiological characteristics of a sample of patients with PPS. Most published studies of patients with chronic poliomyelitis do not focus specifically on PPS; rather, they include the syndrome as part of a more general analysis. Although our patients were selected at random, we feel that the number of patients with PPS is sufficiently representative for our results to merit consideration. To our knowledge, this is the study with the largest sample of patients with PPS conducted to date. However, data were gathered retrospectively from medical histories, which resulted in missing data for some variables.

The main difficulty of studying PPS arises from the limitations inherent to the diagnosis of this entity. The diagnostic criteria for PPS are subject to interpretation both by patients and by healthcare professionals, which may lead to differences between centres or specialists in the percentage of patients diagnosed with the condition. Although several hypotheses have been postulated,3 little is known about the aetiopathogenesis of PPS, which may explain the imprecision of diagnostic criteria. We should also mention the social and work-related determinants and historical factors surrounding PPS and poliomyelitis itself. Very few series have been published that allow us to evaluate the application of these criteria.

In those series, the frequency of PPS ranges from 25% to 80%.8,9 Our sample displayed high prevalence of PPS, with 77.5% of the initial sample being diagnosed with the condition. However, we should bear in mind that our study is not population-based, but rather included patients seeking consultation at a poliomyelitis unit. Most patients visiting our unit had presented clinical changes; furthermore, professionals working at the unit are probably more familiar with these symptoms than general neurologists. Both factors may have had an impact on diagnosis of the entity based on the currently available criteria. Besides clinical symptoms, EMG alterations constitute the only known marker of PPS; however, failure to detect signs of acute denervation does not rule out a diagnosis of PPS according to the diagnostic criteria.

Most of our patients presented acute poliomyelitis in the decade prior to the first vaccination campaigns in Spain, starting in 1963. As a result of delays in administering vaccines, many individuals contracted the infection during those years. The poliomyelitis epidemic started approximately 10 years later in Spain than in other countries, which may explain the fact that Spanish studies on the topic were also conducted at a later time. The only descriptive study of patients with poliomyelitis sequelae in Spain was published in 2005; in this study, Águila-Maturana et al.7 describe the condition of 37 patients. As the variable “post-polio” was not considered in the evaluation or selection of participants in the study, the sample cannot be compared to our own. Despite these differences, we may compare some of our data to those from previous studies.

Mean age at onset of acute poliomyelitis was 24.54 months in our series; this age is similar to that reported by Águila-Maturana et al.7 However, other authors have reported older mean ages, at approximately 6 years.10

Older age at onset of acute poliomyelitis has been considered a risk factor for greater severity of poliomyelitis.6,7,11 In our series, no association was found between age at onset of acute poliomyelitis (below vs above 2 years) and severity of the infection (need for iron lung and/or involvement of 3-4 limbs).

Some 5% of our patients had been treated with an iron lung; use of this treatment ranges from 5% to 15% according to the literature.5 In the study by Águila-Maturana et al.,7 13.5% of patients needed iron lung treatment; Halstead5 reports a rate of 53%. While Águila-Maturana et al.7 suggest that these differences may be due to older age at onset of acute poliomyelitis, our study found no difference in the age of infection between patients who did and did not require this treatment. We may have identified a difference had our sample included more patients considerably older than 2 years at the time of primary infection, although we cannot rule out the impact of early diagnosis, the availability of centres offering this treatment,1 or the possibility that patients with more severe poliomyelitis may have died.

Mean age at onset of symptoms compatible with PPS was 52.4 years, with a mean period of disease stability of 49 years; this value is higher than those reported by other Spanish authors, with periods ranging from 38.7 to 41 years.7,12 International series report highly variable stability periods, ranging from 8 to 71 years.13–15 No clear explanation has been found for these differences. We believe that they may be explained by difficulties in correctly identifying symptoms, since some patients already experience pain or tiredness during the stability period, which makes it difficult to determine when a true change occurs. Furthermore, interpretation of symptoms is subjective, which may result in errors in identifying symptom onset.

The prevalence of PPS is higher in women. In our sample, 57.7% of patients were women, in line with the results of other studies.7,16 Furthermore, women presented symptoms of PPS at a younger age, between 40 and 50 years, while most men presented symptom onset in the following decade of life. Fatigue and tiredness were more frequent in women, although the reason for this is unclear.

At the time of diagnosis, 46.4% of patients needed a wheelchair and 26.1% were unable to walk. The need for a new orthosis offers more objective information on functional worsening. In our series, 24% of patients diagnosed with PPS required a new orthosis.

Pain was the most frequent symptom in our sample, affecting 85% of patients. This is similar to the rate reported by Agre et al.17 and higher than those reported by other authors, at 30%.18,19 Medical histories include more or less explicit notes on pain, depending on its importance in the opinion of both the patient and the healthcare professional interviewing the patient. We believe that our results reflect the frequency and impact of pain in patients with PPS reasonably well. Recent studies seem to confirm the idea that patients with poliomyelitis present a lower pain threshold, which would support our hypothesis.20

Our patients frequently reported fatigue and/or tiredness (65.5% and 57.7%, respectively). These frequencies are similar to those observed in some other series,7 but lower than those described by authors including Halstead and Rossi11 and Agre et al.,17 who report frequencies of 89% and 83%, respectively. This symptom was not evaluated with specific scales in most cases (including our series); comparison between studies should therefore be made with caution.

Approximately 40% of patients reported loss of strength in one or more limbs; this percentage is lower than those reported by most studies, with frequencies ranging from 30% to 100%.7,15,19 These differences are probably explained by the fact that most studies did not use specific tools for quantifying loss of strength (strength was also not systematically quantified in our study). Furthermore, some studies only included patients explicitly reporting loss of strength, while others detected the symptom in a physical examination. We should also bear in mind that most studies include both patients with poliomyelitis sequelae and those diagnosed with PPS.

Cognitive complaints are not rare among patients with PPS. However, no study has demonstrated the presence of specific cognitive disorders in patients with the syndrome.21 It is unclear whether attention and memory alterations are caused by PPS or by an unrelated, concurrent disorder.22 According to a study conducted in 2000, attention and memory alterations reported by patients with PPS may be linked more to physical or psychological manifestations of the disease than to objective deterioration of cognitive performance.21 There is no evidence that general or mental fatigue affects cognitive function in patients with PPS.23 Interestingly, all of our patients with cognitive complaints repeatedly presented neuropsychological alterations, particularly in attention, memory, and executive function. Some authors have attempted to link reticular formation and hypothalamic involvement in PPS with impaired attention and greater fatigue.22 Other potential contributing factors include age-related loss of the functional reserve and chronicity-related maladaptation, although neither of these hypotheses has been confirmed. Although depression scales were not systematically administered in our sample, 30% of patients reported clear depressive symptoms. This percentage is similar to those reported in other studies.24 According to the literature, psychological disorders seem not to be responsible for the onset or intensity of the new symptoms of PPS.22

Patients with the syndrome may present bulbar symptoms, such as dysphagia.25 This suggests that bulbar neurons also undergo slow, progressive deterioration, as occurs with the nerves of the limbs.26 However, 32 patients from our series underwent videofluoroscopy due to self-reported dysphagia, with no specific alterations being detected. These complaints may have been due to muscle fatigue rather than to muscle weakness not observable in videofluoroscopy.

As mentioned previously, EMG is the only complementary test able to confirm history of poliomyelitis and to provide a pathophysiological explanation for the patient's worsening condition. Single-fibre EMG may reveal increased jitter and blocking, which results in instability of motor unit excitability; these findings are suggestive of PPS, but no association has been demonstrated with the symptoms observed in these patients.3 In our series, 59% of patients with PPS presented some of these EMG alterations. No statistically significant association was found between presence of EMG alterations and severe motor involvement (use of the iron lung and/or 3-4 affected limbs) (P=.059). We did find a significant positive association between self-reported loss of strength and presence of EMG alterations (P<.005), which supports the value of EMG in assessing patients with PPS. However, a considerable number of our patients did not report loss of strength, and therefore did not undergo EMG studies; this may have resulted in the loss of relevant data. Prospective studies including objective assessment of loss of strength and performing EMG studies at different times are needed to confirm the usefulness of EMG for distinguishing between patients with and without loss of strength and informing on disease progression.

We also observed a statistically significant association between loss of strength and ability to walk; although this may seem contradictory, it may be explained by the fact that patients who are unable to walk are less likely to detect loss of strength than those who are able to do so, in whom motor changes may be more noticeable.

ConclusionsThe currently available diagnostic criteria for PPS may not be sufficiently objective to characterise an entity with uniform clinical characteristics.

Differences between centres in the frequency of patients diagnosed with PPS may be due to the subjectivity and non-specificity of the diagnostic criteria, which are based exclusively on clinical findings. Furthermore, many of these symptoms may overlap with those of other patients with chronic disability, regardless of the aetiology. EMG is the only tool able to detect pathophysiological changes responsible for these patients’ functional worsening, as our own results demonstrate. However, well-designed clinical trials should be conducted to confirm the usefulness of EMG in diagnosing and following up patients with PPS. Serum or cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers may be explored, although this line of research may be difficult due to the current epidemiology of poliomyelitis.

The social, work-related, and legal implications of a diagnosis of PPS are partly responsible for the current definition of the disease. Although this influence is unlikely to disappear, we believe that a classification of different subtypes of PPS may improve patient management.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sáinz MP, Pelayo R, Laxe S, Castaño B, Capdevilla E, Portell E. Describiendo el síndrome pospolio. Neurología. 2022;37:346–354.