Very few studies describe the demographic and social profile of epilepsy in vulnerable low-income populations.

MethodsObservational, descriptive, cross-sectional study prospectively recording data from all patients diagnosed with epilepsy who attended a specialist neurology consultation between January and March 2014. Data were analysed using descriptive epidemiology tools.

ResultsA total of 107 patients were evaluated, of whom 24.2% were illiterate and only 10.2% had completed a higher education programme. Most of the patients (86.8%) had a low socioeconomic status; 73.8% were single and 76.7% were unemployed. The main risk factors for epilepsy in this population were recorded as follows: delayed psychomotor development (n=24, 22.4%), head trauma (n=16, 14.9%), and central nervous system infection (n=13, 12.1%). Most patients (70.1%) responded to antiepileptic drugs (controlled cases) and 15.4% (n=15) had drug-resistant epilepsy (refractory cases).

ConclusionThe demographic and clinical profiles of the patients included in this study resemble those published for high-income populations; differences are mostly limited to aetiological classification and risk factors. The social profile of the patients evaluated in this study shows high rates of unemployment, illiteracy, and single marital status. These findings seem to be more frequent and prevalent in this group than in high income populations.

Existen pocos estudios que demuestren el perfil demográfico y social de la epilepsia en poblaciones vulnerables y de bajos recursos económicos.

MétodosEstudio observacional, descriptivo, de corte transversal, en donde se registraron prospectivamente los datos de todos los pacientes con diagnóstico de epilepsia que asistieron a la consulta especializada de neurología durante el periodo comprendido entre enero y marzo del 2014. Se analizaron los datos utilizando herramientas de la epidemiología descriptiva.

ResultadosSe valoraron un total de 107 pacientes, de los cuales el 24,2% son analfabetas, y solamente el 10,2% completó estudios de educación superior. El 86,8% de los pacientes viven en un estrato socioeconómico bajo y cerca del 73,8% son solteros. El 76,7% se encuentra desempleado. Los principales factores de riesgo para epilepsia documentados en esta población fueron: retraso en el desarrollo psicomotor (n=24, 22,4%), trauma craneoencefálico (n=16, 14,9%) e infección del sistema nervioso central (n=13, 12,1%). La mayoría de los pacientes (70,1%) son respondedores a los fármacos anticonvulsivos (controlados) y el 15,4% (n=15) son resistentes (refractarios).

ConclusiónEl perfil demográfico y clínico de los pacientes incluidos en este estudio es similar a los datos publicados en poblaciones de altos recursos económicos, la diferencia parece fundamentarse en la clasificación etiológica y los factores de riesgo. El perfil social de los pacientes evaluados en este estudio se caracteriza por desempleo, analfabetismo y soltería. Estos datos, en comparación con poblaciones de altos recursos económicos, parecen ser más frecuentes y prevalentes.

Epilepsy is a chronic disease defined by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) as a brain disorder characterised by a predisposition to generate epileptic seizures which leads to neurobiological, cognitive, psychological and social consequences.1 Recently published studies have shown that epilepsy is a prevalent disease with a high social and economic impact, and it is more frequent in countries with low financial resources. The approximate prevalence of active epilepsy (seizures during the last 5 years) in developed countries reaches 5.8 per 1000 population, compared to 15.4 per 1000 population in low-income countries.2 The most recently published study in Colombia reported an overall prevalence of 11.3 per 1000 individuals. Regional variations are small with the exception of the eastern region, where prevalence is 23 per 1000 population.3 Hospital Occidente de Kennedy is a public institution in Bogotá (Colombia) which provides care to a mostly low-income population with a high level of social vulnerability. We decided to conduct this study to describe the demographic and social profile of the patients and identify those variables related to social vulnerability and low incomes.

Materials and methodsObjectiveThis study aims to describe the most relevant clinical, demographic, and social characteristics of patients diagnosed with epilepsy who visited the neurology department at Hospital Occidente de Kennedy between January and March 2014.

Study populationOur population included patients attending the neurology department at Hospital Occidente de Kennedy in Bogotá, Colombia and diagnosed with epilepsy in the period stated above. Hospital Occidente de Kennedy is a public hospital located in Bogotá. This tertiary care hospital provides care to residents of the locality of Kennedy (Bogotá, Colombia) and its health districts, representing a total approximate population of 2741000 people according to national statistical data. Most residents have a low socioeconomic level; Kennedy has the highest unemployment rate (16.3%) of any locality in Bogotá, therefore also exceeding the overall unemployment rate in Bogotá (13.1%). Of the population of Kennedy, 53% is regarded as below the poverty threshold while 13.3% is indigent. Hospital Occidente de Kennedy is a reference centre for neurological diseases. A total of 2361 patients diagnosed with epilepsy were assessed here in 2013, including patients seen in the emergency department and in external consultations, for a daily average of 6.4 evaluations. All patients included in this study were assessed in the neurology outpatient clinic by a clinical neurologist employed by the hospital.

MethodsThe study design is observational, descriptive, and cross-sectional. We prospectively recorded data from all patients diagnosed with epilepsy and assessed in our neurology clinic between January and March 2014. The definition of epilepsy used in this study was based on the 2010 ILAE report defining it as a brain disorder characterised by a predisposition to generate epileptic seizures, which leads to neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences.1 Epilepsy cases were diagnosed and classified using a review of the clinical history, medical interview, electroencephalogram, videotelemetry (when required), brain magnetic resonance, and neuropsychological assessment (when required). During the consultation, the neurologist filled out the data collection form, which included sociodemographic variables (age, sex, marital status, educational level, social health insurance scheme, social category, current employment, and need for a caregiver) and clinical variables (family history of epilepsy, epilepsy risk factors, age at diagnosis, type of seizure, probable aetiology of epilepsy, antiepileptic drugs [AEDs], and trigger factors).

Epilepsy risk factors were defined as the clinical conditions that generate a permanent predisposition to experiencing epileptic seizures and that increase probability of presenting epilepsy. The assessed risk factors were: history of perinatal disease, delayed psychomotor development, head trauma, central nervous system infection, central nervous system neoplasm, cerebrovascular disease, febrile convulsions during childhood, and neurocutaneous syndromes. The probable aetiology of epilepsy was determined based on the ILAE classification of 20101 which states that epilepsy can be categorised into 3 types: structural and metabolic (trauma, infection, cerebrovascular diseases, among others); genetic, referring to conditions due to a presumed genetic defect in which seizures are the core symptom of the disease; and ‘unknown cause’, referring to an unknown neutral aetiology whose cause could not be determined at the time of the assessment.

We included all patients older than 15 and diagnosed with epilepsy, excluding those patients not willing to participate, those with a cognitive deficit restricting the quality of the information, patients not accompanied by any family members able to confirm the data, and those who had undergone epilepsy surgery. We excluded patients treated with epilepsy surgery because in our hospital, these patients are assessed in an epilepsy clinic and cannot be treated in general neurology clinics for administrative reasons; instead, they are immediately referred for assessment by the epilepsy surgery team. Treatment adherence was assessed by reviewing the clinical history and the medical interview; this information was confirmed by the patient's family member or companion. We analysed data using descriptive epidemiology tools, including calculations of central tendency and dispersion measurements for quantitative variables, and estimates of absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables.

ResultsDemographic dataDuring the period between January and March 2014, we assessed a total of 305 patients diagnosed with epilepsy in our outpatient neurology clinic. Since we excluded a total of 198 patients; the total number of patients analysed was 107. This group comprised 64 men (59.8%) and 43 women (40.1%), with a mean age±standard deviation of 42.7±16.7 years and an age range of 16 to 82 years.

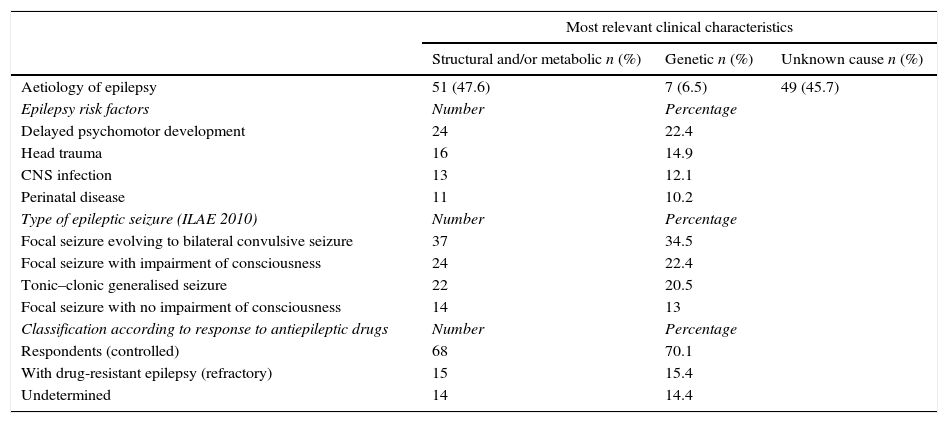

Clinical dataOf the 107 patients included in the study, 80 (74.7%) did not have a family history of epilepsy and only 17 (15.8%) mentioned a family history of epilepsy in first- or second-degree relatives. The family history of the remaining 10 patients was unclear. The main epilepsy risk factors found in this population were as follows: delayed psychomotor development (n=24, 22.4%), head trauma (n=16, 14.9%), central nervous system infection (n=13, 12.1%), and perinatal disease (n=11, 10.2%) (Table 1). Average age at epilepsy diagnosis was 21.7±20.8 years, with a range of 0 to 82 years. Seizure types were classified using the ILAE's 2010 classification system and only the most frequent type was listed per patient: focal epilepsy evolving to bilateral convulsive (secondarily generalised) seizure in 34.5% (n=37), focal seizures with impairment of consciousness (complex focal) in 22.4% (n=24), tonic-clonic generalised seizures in 20.5% (n=22), and focal seizures with no impairment of consciousness (simple focal) in 13% (n=14). Epileptic seizures could not be classified in 10 patients (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics.

| Most relevant clinical characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural and/or metabolic n (%) | Genetic n (%) | Unknown cause n (%) | |

| Aetiology of epilepsy | 51 (47.6) | 7 (6.5) | 49 (45.7) |

| Epilepsy risk factors | Number | Percentage | |

| Delayed psychomotor development | 24 | 22.4 | |

| Head trauma | 16 | 14.9 | |

| CNS infection | 13 | 12.1 | |

| Perinatal disease | 11 | 10.2 | |

| Type of epileptic seizure (ILAE 2010) | Number | Percentage | |

| Focal seizure evolving to bilateral convulsive seizure | 37 | 34.5 | |

| Focal seizure with impairment of consciousness | 24 | 22.4 | |

| Tonic–clonic generalised seizure | 22 | 20.5 | |

| Focal seizure with no impairment of consciousness | 14 | 13 | |

| Classification according to response to antiepileptic drugs | Number | Percentage | |

| Respondents (controlled) | 68 | 70.1 | |

| With drug-resistant epilepsy (refractory) | 15 | 15.4 | |

| Undetermined | 14 | 14.4 | |

The probable aetiology of epilepsy according to the classification system in the 2010 ILAE report was structural and/or metabolic in 47.6% (n=51), followed by unknown cause in 45.7% (n=49). Genetic aetiology represented 6.5% of the cases (n=7) (Table 1).

Regarding current antiepileptic treatment, 57.9% of the patients (n=62) were receiving polytherapy at time of assessment (2 or more AEDs). Of these 62 patients, 46 (67.7%) had been on polytherapy for more than 24 months, and 7 (11.2%) had been polymedicated between 12 and 24 months. The most frequently used antiepileptic drugs were carbamazepine, valproic acid, lamotrigine, phenytoin, clonazepam, levetiracetam, lacosamide, and vigabatrin.

Drug-resistant epilepsy is a clinical condition defined by the ILAE as failure of adequate trials of 2 tolerated and appropriately chosen and used antiepileptic drugs (whether as monotherapies or in combination) to achieve sustained seizure freedom. Seizure freedom is lack of seizures during at least 3 times the longest pretreatment interseizure interval in the preceding year, or 12 months, whichever is longer. Using this framework, we can classify patients with epilepsy into 3 large groups: those who respond well to antiepileptic drugs, those whose epilepsy is resistant to antiepileptic drugs, and unclassified patients (undefined) at the moment of the assessment, who can later be classified as responders and non-responders to drug treatment. According to this definition, of the 107 patients in our population at the beginning, 10 could not be classified; of the remaining 97 patients, 70.1% (n=68) of them were responding to antiepileptic drugs (controlled), 15.4% (n=15) had drug-resistant (refractory) epilepsy, and 14.4% (n=14) were classified as ‘undefined’ at the time of assessment (Table 1).

Most of the patients included in our study presented good adherence to medical treatment and only a few factors triggering seizures were documented. Nine patients reported irregular use of antiepileptic drugs (8.4%), 5 patients referred exacerbation of seizures during menstruation (4.6%), and 4 patients referred exacerbation of seizures due to frequent consumption of alcohol (3.7%). Of the 9 patients who referred irregular adherence to antiepileptic treatment, 5 (5.55%) reported that discontinuing drugs was due to administrative problems related to delivery.

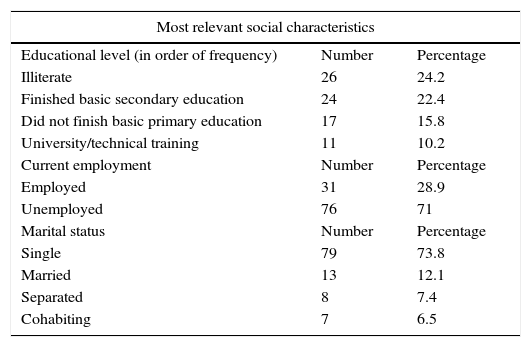

Social dataRegarding educational level, 26 patients (n=26, 24.2%) were illiterate, understood here as the inability to read and write due to lack of education. The Colombian school system is divided into a basic primary level (grades 1 through 5) and a basic secondary level (grades 6 through 11). Higher education includes technical schools and universities. According to this system, 24 of our patients (22.4%) had finished basic secondary education, 17 patients (15.8%) had not finished basic primary education, and only 11 patients (10.2%) had completed higher studies consisting of technical or university education (Table 2).

Social characteristics.

| Most relevant social characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Educational level (in order of frequency) | Number | Percentage |

| Illiterate | 26 | 24.2 |

| Finished basic secondary education | 24 | 22.4 |

| Did not finish basic primary education | 17 | 15.8 |

| University/technical training | 11 | 10.2 |

| Current employment | Number | Percentage |

| Employed | 31 | 28.9 |

| Unemployed | 76 | 71 |

| Marital status | Number | Percentage |

| Single | 79 | 73.8 |

| Married | 13 | 12.1 |

| Separated | 8 | 7.4 |

| Cohabiting | 7 | 6.5 |

Socioeconomic levels in Colombia are defined according to the classification of residential buildings eligible for public services. Socioeconomic levels used to classify dwellings and properties are ranked from 1 to 6, with 1 being the lowest stratum and 6 the highest. With this in mind, 71 of the 107 patients (66.3%) belonged to socioeconomic level 2; 22 patients (20.5%) belonged to level 1; 12 patients (11.2%) belonged to level 3; and only 2 patients (1.86%) were classified in level 5.

Regarding marital status, 79 patients (73.8%) were single, 13 patients (12.1%) were married, and 8 patients (7.4%) were divorced (Table 2).

Regarding employment at the time of assessment, 76 patients (71%) were unemployed and only 31 patients (28.9%) were actively working. Of the 76 unemployed patients, 34 (44.7%) reported that unemployment was secondary to the disease; the remaining 42 did not associate unemployment with the underlying disease (epilepsy) (Table 2). Approximately 34.5% of the included patients (n=37) required a permanent caregiver; only 3 of them (8.1%) reported that their caregiver was drawing a salary for that role.

DiscussionSeveral social, labour-related, demographic, and clinical factors have an impact on epilepsy. Sex and race are demographic factors that seem to affect the presentation of epilepsy in populations with low incomes. This was shown by a study conducted by Kaiboriboon et al.,4 who reported that epilepsy in low-income populations was more frequent among adult black men with previous comorbidities and/or incapacitating conditions. These data support our own results; 59.8% of our patients were men with a mean age of 42.7 years. However, given the sample size, the sampling strategy, and the study methodology, we cannot state that epilepsy in our sample is more frequent in adult men than in other groups; therefore, further population-based analytical studies will have to be conducted to confirm this hypothesis.

Explanations of why men might present epilepsy more frequently than women vary greatly. The explanation we suggest is based on the risk factors for epilepsy, especially head trauma and cerebrovascular accidents, which are frequent and incapacitating in vulnerable, low-income populations like this one. In Colombia, both of these factors are more frequently found in men than in women.5

Educational level is one of the most important variables in the social profile of epileptic patients, and our study reports a low educational level for most of the patients; however, this finding is not exclusive to low-income populations. The REST-1 group showed that in some European countries (Italy, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, England, Portugal, and Russia), epileptic patients had fewer years of study than the general population, presenting a social profile characterised by low educational level, unemployment, and single marital status.6 The REST-1 group also reported that only 13% of the patients with epilepsy from the above mentioned countries had completed a course of higher education (university); this figure is quite similar to that found in our population (10.2%). The difference in the educational profile resides in the percentage of illiteracy; in our study, we found illiteracy in 24.2% of our patient population. A much lower percentage is reported in European populations, at only 2%.6

Although our sample does not reflect the educational profile of all epileptic patients in our setting due to its size and the sampling methodology used, we may still hypothesise that illiteracy in this vulnerable low-income population is more prevalent than in higher-income populations. Low educational level has a significant effect not only on the social profile of epileptic patients, but also on the clinical presentation of epilepsy. It may increase the risk of poor seizure control and the need for polytherapy.7

Unemployment is an important factor of the social profile of epileptic patients; in our study, we found a rate of 76.7%, which is high compared to populations with high incomes. A study of 1009 patients conducted in the Netherlands reported an unemployment rate of about 49%8 in epileptic patients. Another study conducted in England reported an unemployment rate near 46%.9 In addition to being relevant to the social profile of epileptic patients, unemployment is also associated with some interesting clinical variables. For example, the study conducted by Marinas et al.,10 reported that the main factors associated with unemployment were refractory epilepsy, seizures during the last 12 months, low educational level, and polytherapy. Further analytical studies in low income populations should be conducted to determine whether unemployment rates are higher in epileptic patients than in the general population.

Most of the patients in our population were single (73.8%) while only 12.1% were married; these data are similar to those published by Stavem et al.,11 who reported that, compared to the general population, epileptic patients were less likely to be married, employed, or studying. In comparison with populations with high incomes, our population contains a higher percentage of single patients (56% in the REST-1 group vs 73.8% in our sample).6 The study conducted by the REST-1 group also showed that only 2% of the epileptic patients were divorced,6 while this percentage was 7.4% in our study.

Based on the above data, we can hypothesise that rates of unemployment, illiteracy, and single status are much higher in low-income populations, which contributes to their social and labour market vulnerability. However, these data will have to be confirmed by studies that are methodologically prepared to investigate this idea.

The clinical profile of the epileptic patients reported by our study is similar to that observed in populations with high incomes. Regarding type of epileptic seizure, most of our patients (77.2%) presented focal-onset seizures, while 22.6% presented generalised seizures. The epidemiology of types of epileptic seizure is quite variable and depends on multiple factors, such as presence of a reliable clinical history, the diagnostic methods used, the age of the patient, and the probable aetiologies of epilepsy. For this reason, there is no specific clinical pattern to help us determine the most frequent epileptic seizures.12 However, a comparison of our data to those from studies conducted in high-income populations reveals no major differences. Forsgren13 found that the prevalence of focal onset seizures in a Swedish population reached 60%, and generalised seizures, 13%; Luengo et al.14 identified focal-onset seizures in 63% of a Spanish epileptic population, with generalised seizures in 37%. Some studies conducted in such Latin American countries as Chile have reported similar percentages, with focal-onset seizures in 55% and generalised seizures in 40%.15

Regarding epilepsy aetiology, and using the classification proposed by the ILAE in 2010, we observed that seizures in most of our patients have structural or metabolic causes (47.6%), whereas aetiology was unknown in 45.7%, and a genetic cause was only observed in 6.5%. This aetiological profile also presents some similarities to those from studies in high-income populations. In a Spanish population from Barcelona, Torres-Ferrús et al.16 showed that most of their patients presented symptomatic epilepsies (57.2%), followed by cryptogenic epilepsy (19.2%). The cause of epilepsy is unknown in a large percentage of cases due to diagnostic limitations which do not allow doctors to properly determine a structural or genetic cause.17 This clinical profile is similar in other populations with low incomes, and in such African countries as Ethiopia the percentage of patients with epilepsy of an unknown cause may reach 86%.18 Regarding the clinical profile of epileptic patients assessed in this study, it is important to highlight that most had no family history of epilepsy. The main risk factors observed were delayed psychomotor development, head trauma, and central nervous system infection. These findings supported the hypothesis that structural or symptomatic aetiology may be more frequent than genetic or idiopathic aetiology.

The pattern of clinical responses to AEDs in our population is similar to that observed in populations with high incomes. Based on the classification of responses to antiepileptic drugs proposed by the ILAE in 2010, we observed that 70.1% of the patients were adequately controlled, 15.4% were classified as having drug-resistant epilepsy, and 14.4% were undefined. These data are similar to those published by Brodie et al.,19 in a Scottish population in Glasgow, which reported that some 59% of the patients would remain seizure free and therefore be considered controlled; 25% would never attain seizure freedom; and the remaining 16% would present periods of seizure freedom lasting more than one year between relapses.

Methodological limitationsOur study presents the limitations inherent to descriptive studies. This study is based on health centre records rather than a population register, so its sample size and sampling strategy (based on consecutive visits) do not allow us to extrapolate data to the entire population. Nor did we calculate a sample enabling us to create a statistically significant model of the study population (locality of Kennedy in Bogotá, Colombia). For this reason, this study does not enable us to estimate the real value of variables measured in this population. A selection bias is also present since 198 patients of the 305 initially assessed were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were as follows: 85 patients (42.9%) were unwilling to participate or complete the data collection form, 56 patients (28.2%) came to our clinic alone so no family members or companions could corroborate the data they provided, 41 patients (20.7%) were excluded because they exhibited significant cognitive impairment which limited the quality of their information, and 16 patients (8.1%) were excluded due to a history of epilepsy surgery.

ConclusionThe demographic and clinical profile of the patients included in this study resembles profiles described in high income populations; any differences seem to reside in the aetiological classification and risk factors. The social profile of the patients included in our study is characterised by unemployment, illiteracy, and being single. These features seem to be more frequent and prevalent in our patients than they are in high income populations. Further population-based analytical studies should be conducted to confirm these observations in low-income epileptic patients so as to promote comprehensive care strategies adapted to the clinical and demographic profile of this population.

FundingThis study was financed by the authors’ personal resources.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest to declare.

To the members of the neurology department and the postgraduate programme in neurology at the Universidad de la Sabana; Dr Roberto Baquero, Dr Erik Sánchez, Dr Javier Vicini, Dr Gustavo Barrios, Dr María Claudia Angulo, Dr Andrés Betancourt, Dr Marta Ramos, Dr Alejandra Guerrero, Dr Luisa Echavarria, Dr Adriana Casallas, Dr Jorge Ruiz. To the Medical School at Universidad de la Sabana; Dr Camilo Osorio, Dr. Fernando Ríos, Dr María José Maldonado. To the patients of the neurology department at Hospital Occidente de Kennedy. To the directors of Hospital Occidente de Kennedy, Dr Juan Ernesto Oviedo, Dr Wilson Darío Bustos. To the nursing and medical staff in training at Hospital Occidente de Kennedy.

Please cite this article as: Espinosa Jovel CA, Pardo CM, Moreno CM, Vergara J, Hedmont D, Sobrino Mejía FE. Perfil demográfico y social de la epilepsia en una población vulnerable y de bajos recursos económicos en Bogotá, Colombia. Neurología. 2016;31:528–534.