Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most prevalent chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS), affecting more than 2 million people worldwide.1 Psychotic disorders occur in 2%–4% of patients with MS,2,3 occasionally at onset and, more frequently, during the course of the disease.2 One particular type of psychosis is delusional parasitosis (DP) or delusional infestation, originally described by Karl Ekbom as presenile syndrome of delusional dermatozoid parasitic infestation in 1938 (it is also referred to as Ekbom syndrome). Patients with this rare condition have an overwhelming conviction that they are being infested by parasites, worms, bacteria, mites, and/or any other living organism.4 DP also constitutes an infrequent subtype of psychosis, with insidious onset and uncertain origin.5 It has been reported in association with advanced forms of MS, when there is an accumulation of temporal periventricular lesions.2,6,7 We present a patient with an atypical case of primary progressive MS (PPMS) who probably developed DP secondary to an epiphenomenon of the disease activity.

Our patient was a 64-year-old man diagnosed with active PPMS and evidence of disease progression,8 based on a 17-year history of MS since 2001. He presented mild cognitive impairment and required bilateral support with walking canes; at least one hyperintense lesion was present on T2-weighted sequences in periventricular and juxta-cortical locations of the frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes of both hemispheres; and IgG oligoclonal bands were detected in the cerebrospinal fluid by isoelectric focusing. The patient’s score on the Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale was 6.5. In 2016, he attended the hospital emergency department due to a one-month history of strong and irrefutable conviction that he was infested with worms moving under the skin in the area around the mouth and in his toes and fingers. He also claimed that he had brought some of those worms to the hospital in a glass jar. His wife reported that these symptoms had negatively affected his quality of life, especially social functioning. He had never received disease-modifying treatments, only intravenous methylprednisolone to treat right optic neuritis in 2010. The patient had no other relevant medical or surgical history and was transferred to a cubicle to be assessed by the neurology and psychiatry departments.

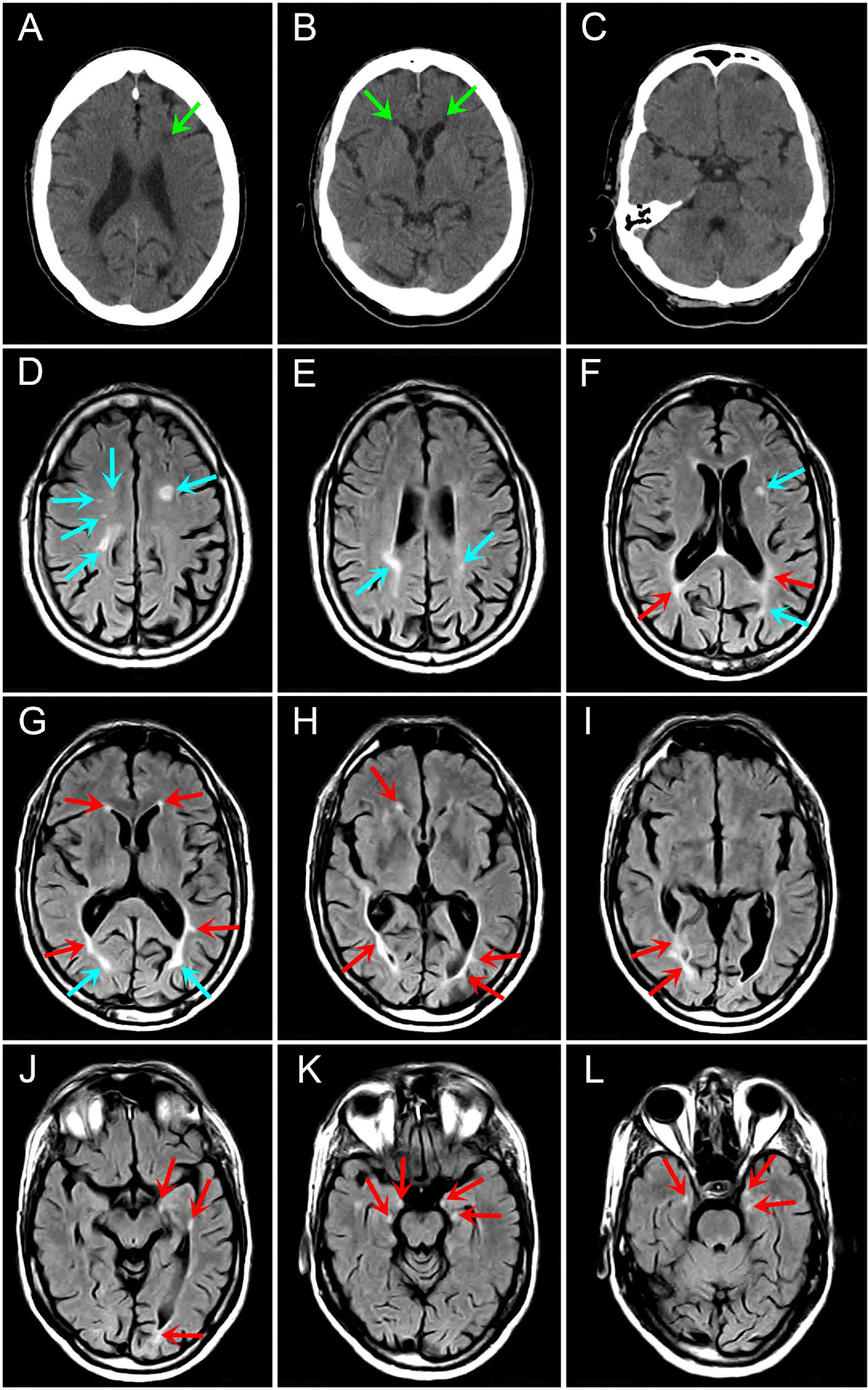

An exhaustive neuropsychiatric assessment did not identify new signs and/or symptoms, except for known severe paraparesis. Optical microscopy of skin samples confirmed signs compatible with epidermal detritus. A complete blood test ruled out toxic/metabolic causes (including vitamin profile, autoimmunity test, thyroid test, blood and urine tests for drugs of abuse, etc) or infectious causes (human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, Brucella, etc), and a head CT scan revealed multiple subcortical and periventricular hypodense areas (Fig. 1A–C). We decided to start treatment not with corticosteroids but with oral risperidone (0.5 mg/12 h), which significantly improved DP in the 24 hours following administration. After 48 hours in the emergency department observation unit, the patient was discharged under close outpatient follow-up by the neurology and psychiatry clinics.

Neuroimaging studies at onset and during patient follow-up. A–C) A head CT study performed at clinical onset (without contrast): non-specific, poorly-defined subcortical hypodense lesions in the periventricular region of both brain hemispheres and in the anterior part of the left frontal lobe (green arrows), probably related to demyelination plaques (patient previously diagnosed with MS). Study revealed no evidence of acute intracranial pathology. Unfortunately, the radiological procedure was suspended, as it was not possible to obtain a neuroimaging sequence using an iodinated contrast medium due to the psychomotor agitation of the patient in the context of a probable allergic reaction to the iodinated medium. D–L) A brain MRI study performed at 3 months (axial FLAIR sequence): images show at least 30 supratentorial hyperintense lesions (red and blue arrows). Some lesions present an ovoid morphology and others are confluent with irregular, poorly-defined borders, which is compatible with MS plaques with sharp edges. The majority of lesions are grouped around the periventricular regions (red arrows), especially in the deep white matter surrounding the temporal horns of the lateral ventricles (J–L). No contrast uptake was observed on T1-weighted sequences. No lesions were found in other regions, including all the spinal cord segments. CT: computed tomography; FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MS: multiple sclerosis.

A brain MRI scan performed at 3 months (Fig. 1 D–L), compared with previous MRI scans, showed new demyelinating lesions located in temporal periventricular areas, with no contrast enhancement after intravenous gadolinium administration and no lesions in other areas, including the spinal cord. The patient was finally diagnosed with 340 [G35] MS; 293.81 [F06.2] psychotic (schizophrenia-like) disorder with delusions due to MS, according to the codification of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5).9 After 6 months of treatment with oral risperidone at 0.5 mg/12 h, the dose was gradually decreased over one month until it was withdrawn; the patient’s clinical situation has remained stable to date.

Correctly interpreting neuropsychiatric alterations is important for all professionals involved in the management of patients with MS, as they have a significant impact on social, professional, and family functioning, and therefore on the quality of life of these patients and their families. Similarly, they affect the level of adherence to disease modifying treatments and treatment schedules prescribed for other medical conditions.2,5,10,11

Although psychotic disorders are infrequent in patients with MS, studies have shown that their prevalence is too high to be attributed to chance alone.2,3,12 The precise aetiology remains unknown. The most widely accepted theory suggests that they may be caused by the direct effect of demyelinating lesions, since patients with MS and psychosis are more likely to present plaques affecting periventricular temporal regions,2,6,7,10,12 as in the case of our patient; such lesions would trigger disruption of the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway, which may explain the aetiopathogenesis of these symptoms.7

The predominant presentation is marked by positive psychotic symptoms (delusional ideas, mainly persecutory) with a relative absence of negative symptoms.12 Treatment of psychosis in patients with MS is the same as in patients without the condition, with corticosteroids and interferon beta to be avoided due to the risk of inducing or exacerbating psychotic symptoms.5,10 Delusion does not generally disappear but may be encapsulated, that is, mitigated by conversion into a partially incorrect inference of reality, without dominating or limiting the patient’s life or functional capacity. Insufficient evidence is available to select any particular antipsychotic drug; second-generation antipsychotics (risperidone, ziprasidone, clozapine, aripiprazole, quetiapine, and olanzapine) at low doses are preferred due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal side effects.2,12

According to the scientific evidence published to date, ours would be the first case of such a distinctive scenario as a manifestation of a PPMS relapse. Therefore, clinicians should consider this possibility when managing DP in patients with MS. Furthermore, a recent study has shown that risperidone significantly reduces microglial and macrophage activation in the CNS in a murine model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, which suggests its potential immunomodulatory activity.13

In conclusion, the fact that the onset of new periventricular temporal lesions coincided with DP, and that the patient rapidly responded to treatment with risperidone, suggests that DP was an acute manifestation of MS. However, given the paucity of clinical trial data from patients with MS to confirm that risperidone positively affects the course of the disease by an anti-inflammatory effect, there is a clear need to design more controlled studies to clarify this hypothesis. Therefore, currently, good physician-patient relationships and an interdisciplinary approach by the neurology and psychiatry departments are essential to implementing holistic, integral, and successful management of these patients.

Finally, we should mention that the main diagnostic limitation to determine the precise spatiotemporal relationship in our case was the inability to administer a contrast medium to the patient during the head CT scan performed during his admission to the emergency department, due to his psychomotor agitation in the context of a probable allergic reaction when we started administering the iodinated contrast. Reactions included moderate urticaria in the trunk and limbs, with no angio-oedema; symptoms resolved after intravenous administration of antihistamines and serum therapy. Since the patient’s family requested that we avoid any invasive test that would not lead to any significant improvement in his functional prognosis, and after the findings of a simple head CT scan and the clinical improvement after onset of treatment with risperidone, we ultimately opted for a conservative interdisciplinary approach. Furthermore, the fact that lesion enhancement was not observed on the brain MRI scan at 3 months after clinical onset does not invalidate diagnosis: while contrast enhancement in acute lesions of patients with MS is reversible, with a mean duration of 3 weeks (although in 3% of the cases it may last >2 months),14 this potential diagnostic limitation was avoided since we were able to use previous MRI scans to confirm the presence of new lesions in the periventricular temporal region bilaterally.

Please cite this article as: León Ruiz M, Mitchell AJ, Benito-León J. Delirio de parasitosis en la esclerosis múltiple: una expresión enigmática de una enfermedad pleomórfica. Neurología. 2020;35:445–448.

This study was presented in poster format at the 68th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology (Valencia, 15–19 November 2016) and as a poster on display at the 3rd Congress of the European Academy of Neurology (Amsterdam, Netherlands, 24–27 June 2017).