Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) and/or the administration of endovenous immunoglobulins (IGEV) are considered the first line treatment for multiple autoimmune-based neurological diseases. According to the scientific evidence collected in several recent guidelines, the efficacy of both treatments is very similar for many of them, however, the current situation of non-self-sufficiency and the real risk of IGEV shortages make it essential to assess TPE as the first therapeutic option.

The objective of this work is to estimate the basic direct costs derived from treatment with RPT compared to treatment with IGEV in immune-mediated neurological diseases in a situation of supposed therapeutic equivalence.

Material and methodsPatients who are treated with IGEV receive a standard dose of 0.4 g/kg weight for 5 consecutive days. Patients treated with RPT with the Terumo-BCT® Optia model cell separator undergo between 5 and 7 sessions, every other day, with a substitution equivalent to 1–1.5 volumes, using 4%–5% albumin as replacement fluid. The calculation of the economic cost, for both types of treatments, in simulation of therapeutic equivalence and safety, has been carried out considering pharmaceutical expenses, calculation of the cost for each dose of IGEV, the detailed costs of consumables, replacement fluids and anticoagulant for RPT, in the worst-case scenario, with central venous catheter (CVC) placement. The price of albumin and immunoglobulins has been adjusted based on the situation of self-sufficiency or dependency and the average value of the last 4 years has been referenced for the calculations. The costs of personnel, hospitalisation, or complications derived from the treatments have not been considered. The prices are indicated in euros including VAT of 4% or 21% as appropriate.

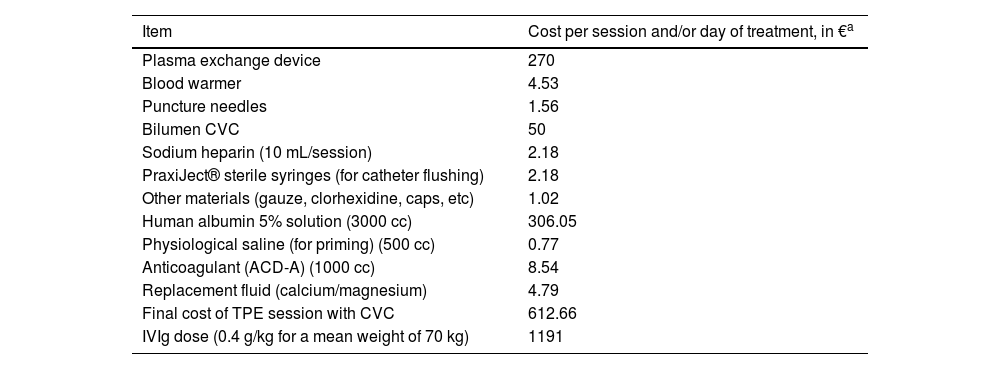

ResultsFor a patient with a mean weight of 70 kg, the estimated final cost per TPR session, with CVC placement, was €612.66; while the cost for each dose of IGEV. (0.4 g/kg) was €1191. The difference is favorable to the RPT: €2279 [€1,666.4–€2,891.7]. The economic difference presented is probably greater in real clinical practice, since many of the patients do not require CVC placement to perform the TPR, and sessions were performed on an outpatient basis.

ConclusionsThe use of TPE in the first line in pathologies in which the clinical results do not present significant differences with the IGEV, optimises the use of blood products and can lead to economic savings. It is necessary to expand this study by including an analysis of the efficacy in our series, as well as the adverse events associated with each type of treatment together with other expenses derived from personnel and hospital admission costs versus the use of outpatient resources (pheresis room).

El recambio plasmático terapéutico (RPT) y/o la administración de inmunoglobulinas endovenosas (IGEV), se consideran el tratamiento de primera línea para múltiples enfermedades neurológicas de base autoinmune. Según la evidencia científica recogida en varias guías recientes, la eficacia de ambos tratamientos es muy similar para muchas de ellas, sin embargo, la situación actual de no autosuficiencia y el riesgo real de desabastecimiento de IGEV, hacen imprescindible valorar como primera opción terapéutica el RPT.

El objetivo de este trabajo es estimar los costes básicos directos derivados del tratamiento con RPT frente al tratamiento con IGEV en enfermedades neurológicas inmunomediadas en una situación de supuesta equivalencia terapéutica.

Material y métodosLos pacientes que son tratados con IGEV reciben pauta estándar una dosis de 0,4 g/kg peso durante 5 días consecutivos. Los pacientes tratados con RPT con el separador celular modelo Optia de Terumo-BCT®, son sometidos a entre 5 y 7 sesiones, a días alternos, con una sustitución equivalente a 1−1,5 volemias, utilizando albúmina al 4–5% como fluido de reposición. El cálculo del coste económico, para ambos tipos de tratamientos, en simulación de equivalencia terapéutica y de seguridad, se ha realizado teniendo en cuenta gasto farmacéutico, cálculo de coste por cada dosis de IGEV, los costes detallados de material fungible, fluidos de reposición y anticoagulante para el RPT, en el peor de los escenarios, con colocación de catéter venoso central (CVC). Se ha ajustado el precio de la albúmina y de las inmunoglobulinas en función de la situación de autoabastecimiento o dependencia y se ha referenciado para los cálculos el valor medio de los últimos 4 años. No se han tenido en cuenta los gastos de personal, de hospitalización, ni de las complicaciones derivadas de los tratamientos. Los precios se indican en euros incluyendo IVA del 4% o del 21% según corresponde.

ResultadosPara un paciente de peso medio de 70 kg, el coste final estimado por sesión de RPT, con colocación CVC, fue 612,66€; mientras que el coste por cada dosis de IGEV. (0,4 g/kg) fue 1191€. La diferencia es favorable al RPT: 2279€ [1666,4€–2891,7€]. La diferencia económica presentada probablemente sea mayor en práctica clínica real, puesto que muchos de los pacientes no precisan colocación de CVC para la realización de los RPT, y se realizaron sesiones en régimen ambulatorio.

ConclusionesEl uso de RPT en 1ª línea en patologías en las que los resultados clínicos no presentan diferencias significativas con las IGEV, optimiza el uso de hemoderivados y puede conllevar un ahorro económico. Es preciso ampliar este estudio incluyendo un análisis de eficacia en nuestra serie, así como de los eventos adversos asociados a cada tipo de tratamiento junto con otros gastos derivados de personal y costes de ingreso hospitalario versus utilización de recursos ambulatorios (sala aféresis).

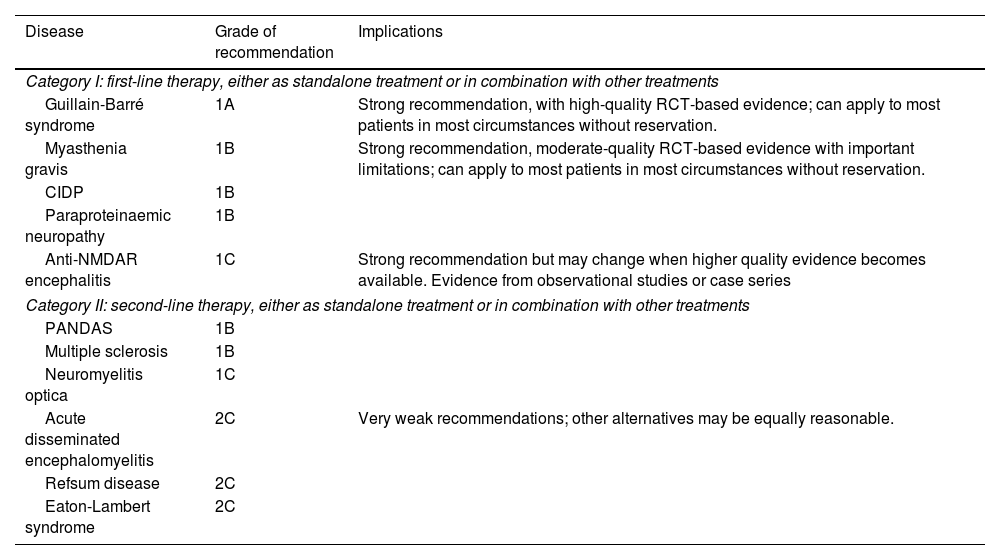

Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) and intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) are considered the first-line treatments for autoimmune neurological diseases (Tables 1 and 2).

Indications for therapeutic plasma exchange according to the 2019 edition of the American Society for Apheresis therapeutic apheresis guidelines.

| Disease | Grade of recommendation | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Category I: first-line therapy, either as standalone treatment or in combination with other treatments | ||

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 1A | Strong recommendation, with high-quality RCT-based evidence; can apply to most patients in most circumstances without reservation. |

| Myasthenia gravis | 1B | Strong recommendation, moderate-quality RCT-based evidence with important limitations; can apply to most patients in most circumstances without reservation. |

| CIDP | 1B | |

| Paraproteinaemic neuropathy | 1B | |

| Anti-NMDAR encephalitis | 1C | Strong recommendation but may change when higher quality evidence becomes available. Evidence from observational studies or case series |

| Category II: second-line therapy, either as standalone treatment or in combination with other treatments | ||

| PANDAS | 1B | |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1B | |

| Neuromyelitis optica | 1C | |

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis | 2C | Very weak recommendations; other alternatives may be equally reasonable. |

| Refsum disease | 2C | |

| Eaton-Lambert syndrome | 2C | |

CIPD: chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; PANDAS: paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

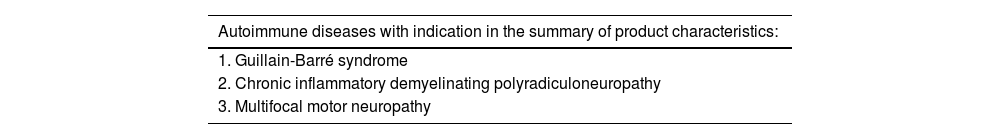

Indications of nonspecific immunoglobulins according to the summary of product characteristics.

| Autoimmune diseases with indication in the summary of product characteristics: |

|---|

| 1. Guillain-Barré syndrome |

| 2. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy |

| 3. Multifocal motor neuropathy |

Both treatments present similar efficacy for several of these diseases, as shown in recent international guidelines.1–6 However, in such other conditions as Guillain-Barré syndrome, where no consistent clinical trials are available, expert consensus statements (such as that published by the American Academy of Neurology) suggest that TPE is more effective and acts more rapidly.

Intravenous immunoglobulins and TPE present similar incidence of adverse effects, although some studies have reported a lower incidence and severity of complications with TPE in some diseases.1,7

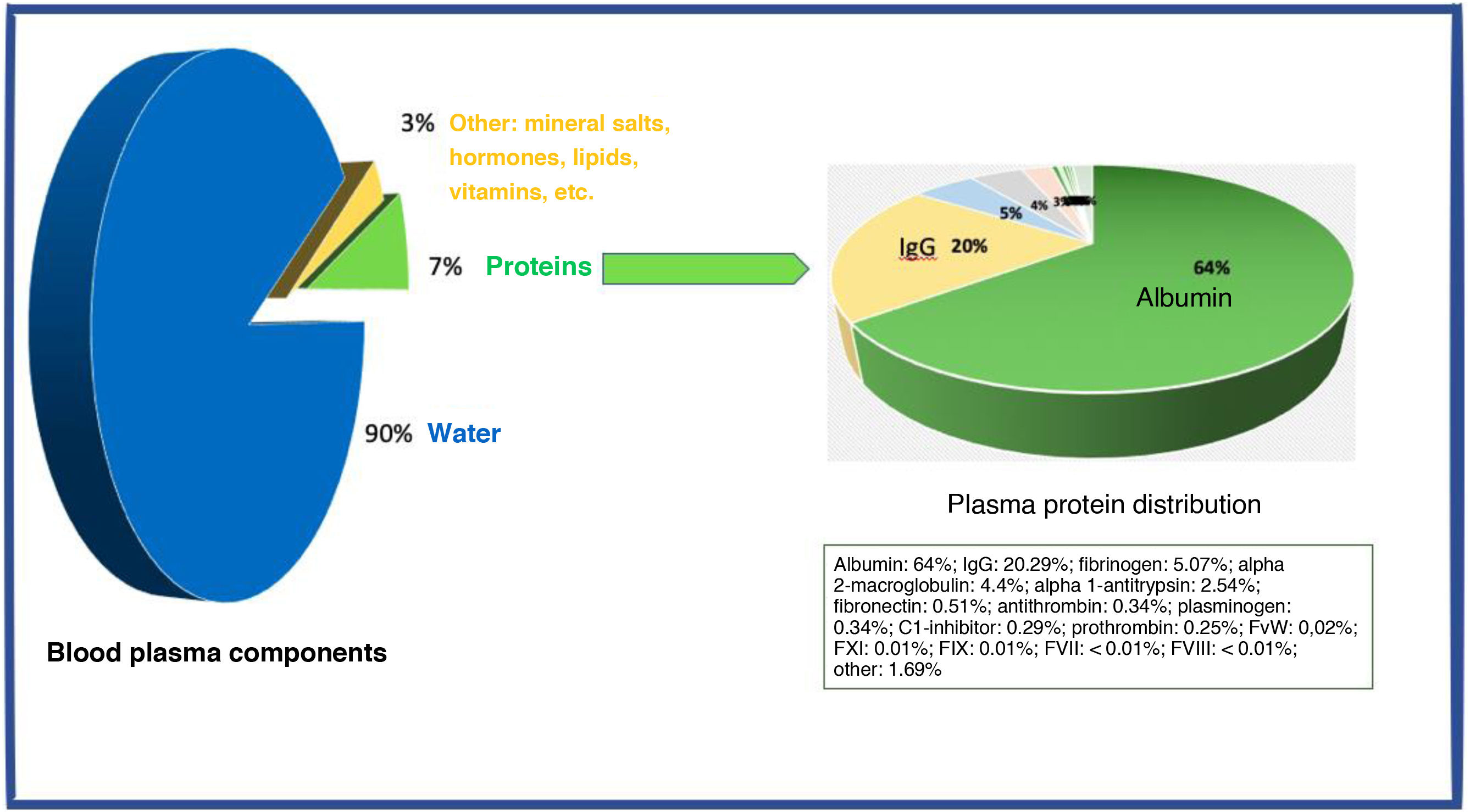

Both treatments rely on plasma derivatives, for which no alternative production process currently exists other than whole blood donation and/or plasmapheresis. Blood plasma, which contains approximately 7% proteins, is the source of numerous plasma derivatives, which undergo fractionation processing for subsequent use in clinical practice. This is the case of nonspecific immunoglobulin G and albumin, both of which play a crucial role in the treatment of autoimmune diseases.8

In Spain, the use of plasma derivatives has increased exponentially over the past 10 years, with an increase of 75%–100%. However, this increased consumption has not been accompanied by an increase in blood donation, with whole blood donations decreasing by more than 6%, leading to a shortage of these medicinal products.9 According to 2016 data from the Spanish Ministry of Health’s annual report, domestic donations barely covered 70% of the demand for albumin, 55% for immunoglobulins, and 40% for factor VIII. Far from improving, in 2021, self-sufficiency for IVIg and albumin fell to 33% and 60%, respectively.10

This trend toward a lack of self-sufficiency in plasma derivatives has been exacerbated by the global decline in blood donations, along with the increased demand for plasma to treat patients with COVID-19 during the pandemic.11,12 The COVID-19 pandemic has made it increasingly difficult to import plasma from other countries to meet the clinical demand of the Spanish population, resulting in significant supply shortages.13,14

Some studies have suggested a potential increase in the incidence of immune-mediated neurological diseases (particularly those related to SARS-CoV-2 infection) as a result of the pandemic; however, this association has not been confirmed in subsequent reviews.15,16 Nevertheless, an increase has been observed in the incidence of one such disease following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.17

The production of raw material for such medicinal products as immunoglobulins decreased as a result of mobility restrictions during the pandemic, leading to supply issues with all authorised and marketed drugs in Spain during the second half of 2021.13 Even in 2023, given the wide range of indications of these products and the challenges associated with their production, the marketing authorisation holder of some formulations continues performing controlled distribution given the limited availability of units, with no estimated resolution date.14

This study aims to highlight the direct economic cost and provide an overview of the indirect costs associated with prioritising TPE as a first-line treatment for immune-mediated neurological diseases, in cases where its indication is at least similar to that of immunoglobulins.

Material and methodsOur centre is a fourth-level hospital complex that serves as the reference centre for neurological diseases in our autonomous community. It has a specialised unit for the treatment of immune-mediated neurological diseases, as well as a therapeutic apheresis unit, run by the haematology and transfusion medicine department. This unit is available for urgent treatment procedures 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

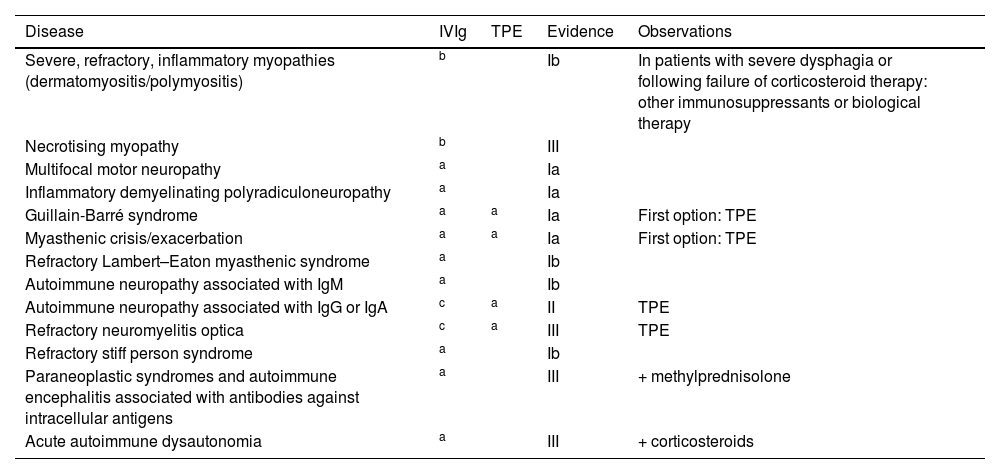

In 2018, a comprehensive review of indications for the administration of IVIg (Tables 1 and 2) culminated in the creation of an intrahospital consensus document, which was disseminated and published on the intranet of the regional healthcare service in January 2019 (Table 3). The document was drafted by a multidisciplinary working group involving specialists from the departments of pharmacy, haematology and transfusion medicine, neurology, nephrology, rheumatology, internal medicine, paediatrics, and intensive care, as well as our region’s blood donation centre. It was subsequently revised based on the available evidence, and incorporated into a project aimed at improving the appropriateness of clinical practice (MAPAC).18

Hospital consensus statement on the indications for intravenous immunoglobulins and therapeutic plasma exchange in neurology.

| Disease | IVIg | TPE | Evidence | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe, refractory, inflammatory myopathies (dermatomyositis/polymyositis) | b | Ib | In patients with severe dysphagia or following failure of corticosteroid therapy: other immunosuppressants or biological therapy | |

| Necrotising myopathy | b | III | ||

| Multifocal motor neuropathy | a | Ia | ||

| Inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy | a | Ia | ||

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | a | a | Ia | First option: TPE |

| Myasthenic crisis/exacerbation | a | a | Ia | First option: TPE |

| Refractory Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome | a | Ib | ||

| Autoimmune neuropathy associated with IgM | a | Ib | ||

| Autoimmune neuropathy associated with IgG or IgA | c | a | II | TPE |

| Refractory neuromyelitis optica | c | a | III | TPE |

| Refractory stiff person syndrome | a | Ib | ||

| Paraneoplastic syndromes and autoimmune encephalitis associated with antibodies against intracellular antigens | a | III | + methylprednisolone | |

| Acute autoimmune dysautonomia | a | III | + corticosteroids |

IgA: immunoglobulin A; IgG: immunoglobulin G; IgM: immunoglobulin M; IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulins; TPE: therapeutic plasma exchange.

Simultaneously, a direct cost analysis comparing TPE against the acquisition costs of IVIg was performed to evaluate the impact of the prioritisation of TPE over IVIg by our region’s clinical management support and continuity of care service.

Among the multiple indications of these treatments, we selected and compared the impact of prioritising treatment with TPE in patients with immune-mediated neurological diseases, assuming at least a neutral scenario in which both treatments had similar clinical efficacy and adverse effects.

We retrospectively reviewed patients diagnosed with neurological diseases and treated with TPE, as recorded in the quality control database (eBDI plus) of the therapeutic apheresis unit, and patients treated with IVIg, as recorded in the hospital pharmacy database.

Patients treated with IVIg received the standard dose of 0.4 g/kg for 5 days, whereas those undergoing TPE completed 5–7 sessions, with exchanges equivalent to 1–1.5 plasma volumes. All TPE procedures were performed with the same model of cell separator (TERUMO BCT Spectra Optia®), using 4%–5% albumin as the replacement fluid every 48 hours (until 2019, we used 5% albumin solutions, which were subsequently adjusted to 4% after a review of the available evidence19).

The economic cost of both treatments took into account the pharmaceutical costs and the cost of consumable materials (Table 4). The pharmaceutical cost was adjusted for the 2019 price of albumin and IVIg, considering the scenario of self-sufficiency or dependency, and the mean value was used. These data were used to estimate the cost of each treatment. Costs associated with healthcare staffing, hospitalisation, and treatment-related complications were not considered.

Cost of consumable materials and replacement fluids used for therapeutic plasma exchange and treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins.

| Item | Cost per session and/or day of treatment, in €a |

|---|---|

| Plasma exchange device | 270 |

| Blood warmer | 4.53 |

| Puncture needles | 1.56 |

| Bilumen CVC | 50 |

| Sodium heparin (10 mL/session) | 2.18 |

| PraxiJect® sterile syringes (for catheter flushing) | 2.18 |

| Other materials (gauze, clorhexidine, caps, etc) | 1.02 |

| Human albumin 5% solution (3000 cc) | 306.05 |

| Physiological saline (for priming) (500 cc) | 0.77 |

| Anticoagulant (ACD-A) (1000 cc) | 8.54 |

| Replacement fluid (calcium/magnesium) | 4.79 |

| Final cost of TPE session with CVC | 612.66 |

| IVIg dose (0.4 g/kg for a mean weight of 70 kg) | 1191 |

CVC: central venous catheter; IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulins; TPE: therapeutic plasma exchange.

We compared the treatments performed before and after the publication of the consensus document (2017–2018 vs 2019–2020), and reviewed the number of patients with a potential indication for TPE who received IVIg, as well as all patients with an indication for IVIg.

To estimate indirect cost savings, we used data from the plasma fractionation reports provided by Grifols® from the reference donation centre. According to the latest report, the mean yield from one litre of plasma was 4.26 g of albumin (Albuplan®) and 27.04 g of immunoglobulins (Plangamma®).

To estimate indirect benefit of donation, we considered the best-case scenario (no donor exclusions or component losses), using an average plasmapheresis volume of 600 cc and an average fresh frozen plasma volume of 270 cc from whole blood donation.

This study was approved by the Research, Innovation, and Knowledge Management Unit, within the registry of research projects not requiring patient consent, and is part of a project entitled “Therapeutic plasma exchange in autoimmune neurological diseases in Spain. A 5-year study” (project no. 3318-2022-0000174, of 22 November 2022).

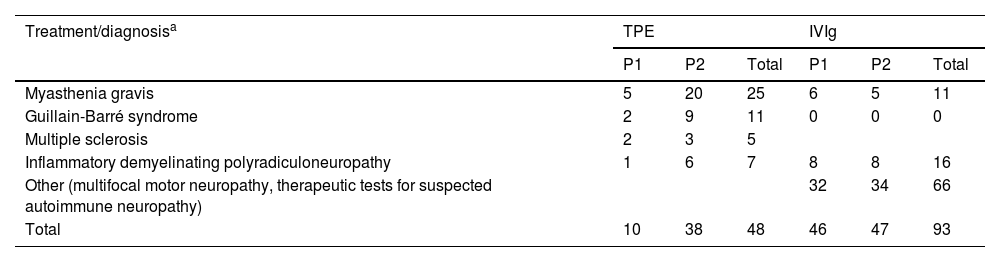

ResultsDuring the study period, our centre treated a total of 141 patients with neurological diseases eligible for this type of treatment. The most prevalent diagnosis was myasthenia gravis, accounting for 52% of cases, followed by Guillain-Barré syndrome in 25.5%. Table 5 breaks down the diagnoses by treatment and period (2017–2018 vs 2019–2020). The number of patients receiving TPE during the second period was nearly 4 times greater.

Diagnoses in our sample, by treatment and period.

| Treatment/diagnosisa | TPE | IVIg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | Total | P1 | P2 | Total | |

| Myasthenia gravis | 5 | 20 | 25 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 2 | 9 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 2 | 3 | 5 | |||

| Inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| Other (multifocal motor neuropathy, therapeutic tests for suspected autoimmune neuropathy) | 32 | 34 | 66 | |||

| Total | 10 | 38 | 48 | 46 | 47 | 93 |

IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulins; P1: period 1 (2017–2018); P2: period 2 (2019–2020); TPE: therapeutic plasma exchange.

The mean number of TPE sessions was 6.3 for both periods, with a median of 7 sessions. The mean age of both patient groups was 61.3 years, with a mean body weight of 70.8 kg and a mean blood volume of 4309 mL.

The neurology department did not observe an increase in the relapse rate in these patients after prioritising TPE as the first-line treatment over IVIg. A small group of patients with autoimmune neuropathies treated with IVIg presented relapses, requiring additional IVIg courses. During the 2019–2020 period, 3 patients with myasthenia gravis were refractory to TPE, and received second-line treatment with IVIg.

Cost estimationTable 4 presents the estimated cost (worst-case scenario) of a TPE session, at €612.66; the total cost of treatment is estimated at €3063.00 to €4288.62, depending on the number of sessions (5–7). On the other hand, the acquisition cost of IVIg for a 70 kg patient is estimated at €5955. In our series, prioritising TPE over IVIg would result in a cost saving of at least €109 393.92.

The treatment of these 48 patients with TPE instead of IVIg as the first-line treatment would have resulted in a direct acquisition cost saving of €285 841.92.

Impact on donationsConsidering the mean albumin yield reported previously (4.26 g/L of plasma), a total of 1577.46 L of plasma would have been required to obtain the 6720 g IVIg potentially saved. In the best-case scenario (no loss or rejection, and maximal use), this would require at least an additional 2630 plasmapheresis procedures (mean volume of 600 cc of plasma) or 6310 whole blood donations. According to 2019 data from our regional donation centre, this translates into an increase of at least 25% in the number of donations or more than a 100% increase in the number of plasmapheresis procedures performed.

DiscussionImmune-mediated neurological diseases1–7 are treated with plasma protein therapies; the plasma used is collected either from voluntary, altruistic donations in many countries, such as Spain, or from paid donations in other countries, such as the United States, the main country from which Spain imports plasma derivatives. The main plasma derivatives used for these patients are IVIg and albumin, with the latter serving as a replacement fluid in TPE procedures.

Approximately 55% of total blood volume is plasma, which is composed of 90% water, 7% proteins, and 3% such other components as mineral salts, hormones, lipids, and vitamins. The 7% of plasma that consists of proteins is the source of numerous plasma derivatives, which are fractionated for routine use in clinical practice. This is the case of nonspecific immunoglobulin G and albumin, both of which play a crucial role in the treatment of autoimmune diseases (Fig. 1).8 As whole blood donations are insufficient to meet the demand for plasma derivatives, selective plasma donation by apheresis is needed.

Production of immunoglobulin products decreased during the pandemic, as mobility restrictions led to a decrease in donations; all authorised drugs marketed in Spain faced supply issues during the second semester of 2021.13 In addition to dose readjustments and administration delays, and to mitigate the impact of shortage of these medications, the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS, for its Spanish initials) authorised the importation of drugs from other countries, at a higher cost, in addition to authorising the sale of several medicinal products in languages other than Spanish.13

Spain’s lack of self-sufficiency (only 33% of IVIg and less than 50% of albumin in 2021)9,10 and the consequent need to import plasma derivatives from countries with donor compensation systems results not only in an increase in health expenditure but also in potential safety concerns, in addition to ethical and consistency issues. The concentration of immunoglobulins in plasma is significantly lower than that of albumin; therefore, treatment with TPE involves less use of plasma derivatives and incurs lower costs than IVIg infusion. From plasma donations in Spain, the average yield is 27.04 g of albumin per litre of processed plasma, versus 4.26 g/L in imported plasma, with acquisition cost of €24.59 per 1 g vial of albumin versus €425.30 per 10 g vial (data from the regional donation centre, Grifols® June 2023 report). Prioritisation of TPE over IVIg in diseases with at least the same level of evidence for effectiveness would not only be cost-effective but also improve the management of plasma derivative resources.

In addition to promoting the optimal clinical use of plasma, the blood component with the highest rate of inappropriate use,20 we consider it urgent to develop protocols for the optimal management of plasma derivatives, not only for neurological diseases but also for any other indication. Implementing these protocols in all hospitals may help address the shortage of IVIg while improving the safety of blood derivatives.

The cost savings associated with prioritisation of TPE over IVIg may even be greater than estimated, as our calculations included the cost of central venous catheters. However, at present, over 80% of the procedures are performed with peripheral venous catheters due to the availability of specialised nursing units, ultrasound, and different types of venous access.

Another measure that may help to reduce the use of plasma derivatives is adjusting albumin concentration for TPE. A concentration of 5% albumin has historically been used as replacement fluid for TPE in our setting; however, serum albumin concentration typically ranges from 4% to 4.5%, decreasing gradually from the age of 20 years, especially after 60.21 Although no clinical trials have compared the use of 4% albumin against 5% albumin, there is evidence on the use of 4% albumin.18 Our data show similar rates of adverse reactions in TPE performed with 4% and 5% albumin. Based on the volume of albumin used in this scenario (2000−3000 mL albumin solution per TPE procedure), adjusting from 5% to 4% albumin results in an additional 20% reduction in albumin consumption, with no impact on clinical outcomes, while maintaining a more physiological blood albumin concentration and reducing the risk of fluid overload.

This study was based on the 8th edition of the American Society for Apheresis therapeutic apheresis guidelines (Table 1). No changes were made in the 2023 edition,22 except for multiple sclerosis (category II, recommendation grade 1A) and neuromyelitis optica (category II, recommendation grade 1B); however, these changes would have little impact on our results.

Currently, following successive reviews of the available evidence19 and confirmation of the safety and effectiveness of TPE, the motor neuropathy unit rarely indicates IVIg, except for patients with multifocal motor neuropathy or those showing poor response to TPE.

Although the indication of TPE has tripled since the publication of the hospital consensus document, a proportionate reduction in the volume of IVIg used for these conditions has not been observed. We believe that the predicted savings may have been underestimated due to the pandemic and a potential increase in the number of diagnosed cases. Despite a lack of robust evidence of an increase in the incidence of neurological diseases,15,16 some international organisations have reported a higher incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome in individuals older than 18 years following vaccination with the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine, but not with the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna vaccines. This potential relationship was not observed in our series.

Our study presents the limitations inherent to its before-and-after, observational, single-centre design. However, its strength lies in the fact that it is based on a prospective registry of TPE procedures performed by trained, experienced personnel from 2 reference units, using real-life data, without exclusions or losses to follow-up. Furthermore, diagnostic and management criteria for these patients have remained consistent during the study period, without changes.

Another limitation inherent to its design is the lack of an age-matched control group, which prevented us from estimating a scenario with greater savings, based on available evidence suggesting greater effectiveness and safety of TPE over IVIg. Furthermore, we did not consider the potential cost savings from performing some sessions on an outpatient basis, or the shorter duration of TPE compared to IVIg administration. Since personnel costs were not considered in direct cost estimation, this study is more of a comparison between pharmaceutical products than between therapeutic techniques.

Another limitation is the fact that hospital departments and units were restructured during the first months of the pandemic, prioritising outpatient treatment to avoid hospital admissions. This led to a significant increase in IVIg prescription and a dramatic decrease (almost a complete halt) in TPE during the first wave of COVID-19.

The retrospective nature of the study constitutes another limitation, as some diagnostic codes may not have been used appropriately. For example, cases of inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy may have been classified as Guillain-Barré syndrome, depending on the terminology used in pharmacy department requests.

ConclusionTherapeutic plasma exchange is a safe treatment option that results in direct cost savings for hospital pharmacy departments and improves the management of IVIg stock (increasing availability of IVIg for patients who need it as first-line treatment and for whom no alternative is available), without increases in the rates of complications, relapses, or readmissions. Despite warnings from the AEMPS,14 we have not experienced stock shortages or treatment interruptions. Furthermore, despite the increased use of albumin, a theoretical 20% cost saving has been observed due to the adjustment in albumin concentration.

Randomised studies should be conducted to compare both treatments, validating the albumin dose used and including medium- and long-term follow-up to monitor clinical efficacy, functional recovery, quality of life, and relapses or exacerbations. Methodology reviews and clinical practice guidelines for plasma and plasma derivatives18,19,21,23 are needed, given the long-standing lack of self-sufficiency, rising costs, and predicted limitations in access.18,19,22

We urge colleagues to strive for the optimal use of plasma derivatives in general, and IVIg in particular,22 as well as other blood components, based on the best available evidence. There is also an urgent need for patient blood management programmes9,24 to achieve self-sufficiency in Europe in the medium term.

FundingThis study has received no funding. It was developed on the initiative of Hospital Universitario de Navarra’s working group for the rational use of immunoglobulins.

We would like to thank the members of our multidisciplinary working group, involving the hospital pharmacy, haematology, neurology, nephrology, rheumatology, and internal medicine departments. We also wish to thank the MAPAC initiative, and all plasmapheresis donors from our autonomous community.