Between 6% and 34% of patients with COVID-19 present neurological symptoms, with headache and myalgia being the most frequent.1 Seizures, on the other hand, are less common.2 The neurotropic nature of SARS-CoV-2 is yet to be confirmed, although the virus is thought to reach the central nervous system either through the haematogenous pathway3 or through a transneuronal pathway via the olfactory nerve.4

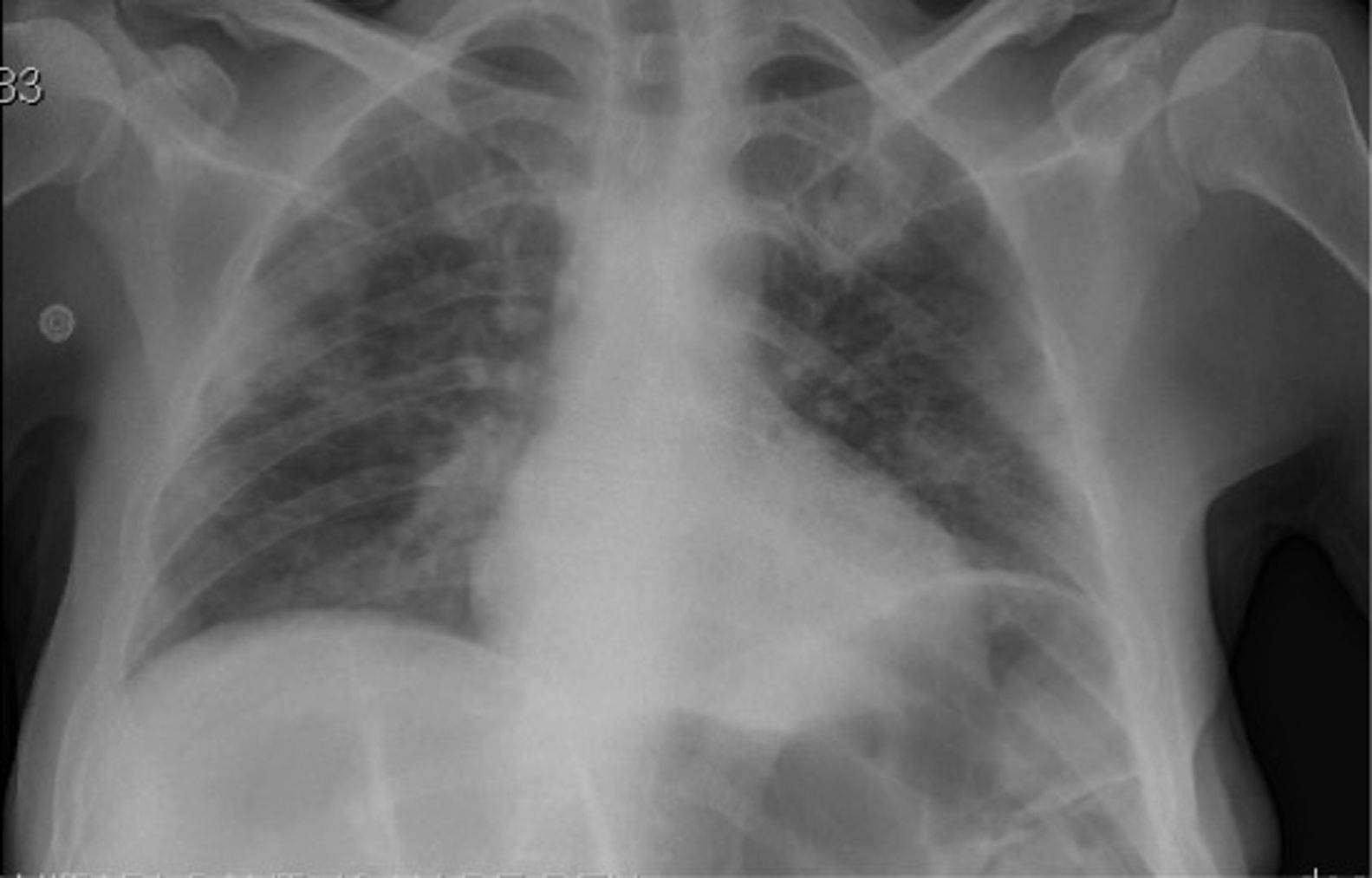

We present the case of a 37-year-old man with history of bilateral ulnar neuropathy and recurrent pneumonia. He also presented moderate intellectual disability, an autistic spectrum disorder, and impulse control disorder. He was institutionalised in a long-stay psychiatry unit specialising in neurodevelopmental disorders and was under treatment with levomepromazine (250 mg/day), haloperidol (15 mg/day), olanzapine (30 mg/day), quetiapine (1000 mg/day), and clomipramine (300 mg/day). He developed fever associated with cough and dyspnoea; a PCR study for SARS-CoV-2 returned positive results. A chest radiography revealed infiltrate in the bases of both lungs (Fig. 1). Blood analysis revealed slight leukopaenia (3500 cells/mm3), moderately elevated infection markers (C-reactive protein: 45.6 mg/L; ferritin: 9186.7 µg/L), and hypertransaminasaemia (ALT: 2692 IU/L; AST: 3160 IU/L; GGT: 127 IU/L), with no evidence of infection by hepatotropic viruses. Arterial blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.49, with pO2 of 68.5 mm Hg and pCO2 of 32.4 mm Hg. With a working diagnosis of bilateral pneumonia and hepatitis secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection, we started treatment with hydroxychloroquine (400 mg/12 h for 5 days), azithromycin (500 mg/day for 5 days), methylprednisolone (250 mg/day for 3 days), and bemiparin sodium (7500 IU/day for 30 days). Twelve days after admission to the internal medicine department, the patient was discharged to the long-stay psychiatry unit, showing significant improvements in clinical (resolution of fever and respiratory symptoms) and laboratory parameters (C-reactive protein: 18 mg/L; ferritin: 641.6 µg/L; ALT: 100 IU/L; AST: 50 IU/L; GGT: 117 IU/L). Two days later, he presented an episode of status epilepticus, presenting as a single, uninterrupted, generalised tonic-clonic seizure of 15 minutes’ duration, which resolved with 4 mg intravenous clonazepam. Neurological examination revealed stupor, absence of fever, a bite wound on the side of the tongue, conjugate gaze deviation to the left, and no meningism or paresis. An electrocardiography study showed sinus rhythm at 96 bpm, with no alterations of repolarisation; QTc was 0.459. Head CT findings were normal (Fig. 2). Blood analysis showed mild leukocytosis (14 500 cells/mm3) and a C-reactive protein level of 31.8 mg/L. Electroencephalography and lumbar puncture were not performed due to clinical improvement and the risk of transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Two days later, the patient presented a second episode, manifesting as an atonic seizure of 3 minutes’ duration. Following this seizure, we started treatment with valproic acid (1500 mg/day) and lacosamide (200 mg/day). Four weeks later, the patient remains seizure-free and has presented a marked improvement in aggressive and impulsive behaviour.

DiscussionThis is the first reported case of tonic-clonic status epilepticus in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection and no previous history of epilepsy. The patient was receiving treatment with psychoactive drugs, which may have lowered the seizure threshold5; however, he had never previously presented seizures, and his treatment schedule had not been altered in the previous 3 months. At the time of the status epilepticus, fever had resolved and respiratory symptoms and levels of infection markers had improved considerably. A head CT scan revealed no abnormalities. While PCR testing of cerebrospinal fluid for SARS-CoV-2 was not performed, we believe that the virus may have played a role in the onset of status epilepticus. Research is ongoing into the neurotropic potential of SARS-CoV-2,4,6 and only one manuscript published to date reports focal status epilepticus, in a patient with symptomatic epilepsy and SARS-CoV-2 infection.7 Some studies report positive PCR results for SARS-CoV-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid in patients with encephalitis.8 We considered it important to report this case, given the increased risk of seizures in patients with intellectual disability9 or receiving antipsychotic drugs.5

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

We wish to thank the healthcare and teaching staff at our unit.

Please cite this article as: López Cuiña M, Chavarría V, Robles Olmo B. Estatus epiléptico convulsivo como posible síntoma de infección por COVID-19 en un paciente con discapacidad intelectual y trastorno del espectro autista. Neurología. 2020;35:703–705.