According to McCormick's 1966 classification system, cerebral vascular malformations are categorised as arteriovenous malformations, venous malformations, capillary telangiectasias, cavernous angiomas, and varix. Dural arteriovenous fistulas were first described in the 1930s and they are regarded as a separate entity.

Dural arteriovenous fistulas account for 10% to 15% of all intracranial arteriovenous lesions and their symptoms and prognosis vary considerably. Some may elicit tinnitus or ocular symptoms, while others may provoke neurological symptoms or intracranial haemorrhage. The Cognard classification is the most widely used to determine the risk associated with dural arteriovenous fistulas in order to make treatment decisions. It rates fistulas in 5 categories, from I to V.1

The Cognard classification is based on different factors, including direction of venous drainage, recruitment, and presence or absence of spinal perimedullary venous drainage. Its 5 categories are described as follows. I: located in the main sinus, with antegrade flow; II: in the main sinus, with reflux into the sinus (IIa), cortical veins (IIb), or both (IIa+b); III: direct cortical venous drainage without venous ectasia; IV: direct cortical venous drainage with venous ectasia; and V: with spinal perimedullary venous drainage. Ectasia is diagnosed when vessel calibre is greater than 5mm or more than 3 times the normal diameter.1

Dural carotid-cavernous fistula is a specific type of dural arteriovenous fistula in which there is abnormal shunting within the cavernous sinus. The cavernous sinus is a vascular network crossed by the intracranial internal carotid artery, which in turn provides various intracranial branches to nerves and to the pituitary gland (meningohypophyseal trunk and inferolateral trunk). The external carotid artery also extends dural branches to the cavernous sinus; these branches anastomose with internal carotid artery branches. The dural arteriovenous fistula gives rise to high-pressure arterial blood entering the low-pressure cavernous venous sinus. This interferes with normal venous drainage of the cavernous sinus and the orbit.

Most dural arteriovenous fistulas are acquired (venous sinus thrombosis, surgery, trauma, spontaneous fistula, etc.).2 The formation of these fistulas has been associated with rupture of an intracavernous aneurysm, fibromuscular dysplasia,3 Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and other collagen vascular diseases, arteriosclerotic vascular disease, pregnancy, etc.

The most common clinical manifestations are orbital venous hypertension, orbital venous congestion, eye proptosis, chemosis, dyplopia due to cranial nerve impairment (III, IV, and VI), impairment in the first branch of the trigeminal nerve (V-1), vision loss, central retinal vein occlusion, retinopathy, glaucoma, and headache.4,5

We present a case of dural carotid-cavernous fistula that initially presented as an atypical recurrent headache.

The patient was a 69-year-old woman with a history of vertiginous syndrome and a cholecystectomy. She was examined due to recurrent right-sided hemicranial headache (predominant in the periorbital region) that had been occurring over 4 months. Headaches appeared almost daily, tended to be more intense at night, and occurred in 2 to 4 episodes per day. These episodes lasted from minutes to hours and were generally described as moderate to intense pain that was oppressive and sometimes pulsating. Accompanying symptoms included conjunctival injection ipsilateral to the pain, an uncomfortable sensation (‘grittiness’) in the right eye, and a sensation of fullness in the right nasal region that occasionally coincided with headaches.

Since onset of these headaches, the patient had also been experiencing short attacks of paroxysmal pain lasting less than 60seconds, described as resembling electric shock and located in the upper right dental arch. Episode periodicity varied throughout the day and the pain was described as moderate to intense with no trigger points or other concomitant symptoms.

The patient had been examined by ophthalmologists and a dentist, and the facial CT and cranial MRI scans that had been performed revealed no significant findings.

She was admitted to the neurology department due to presenting binocular horizontal diplopia in the preceding days. Examination revealed right-sided sixth nerve palsy with no other findings.

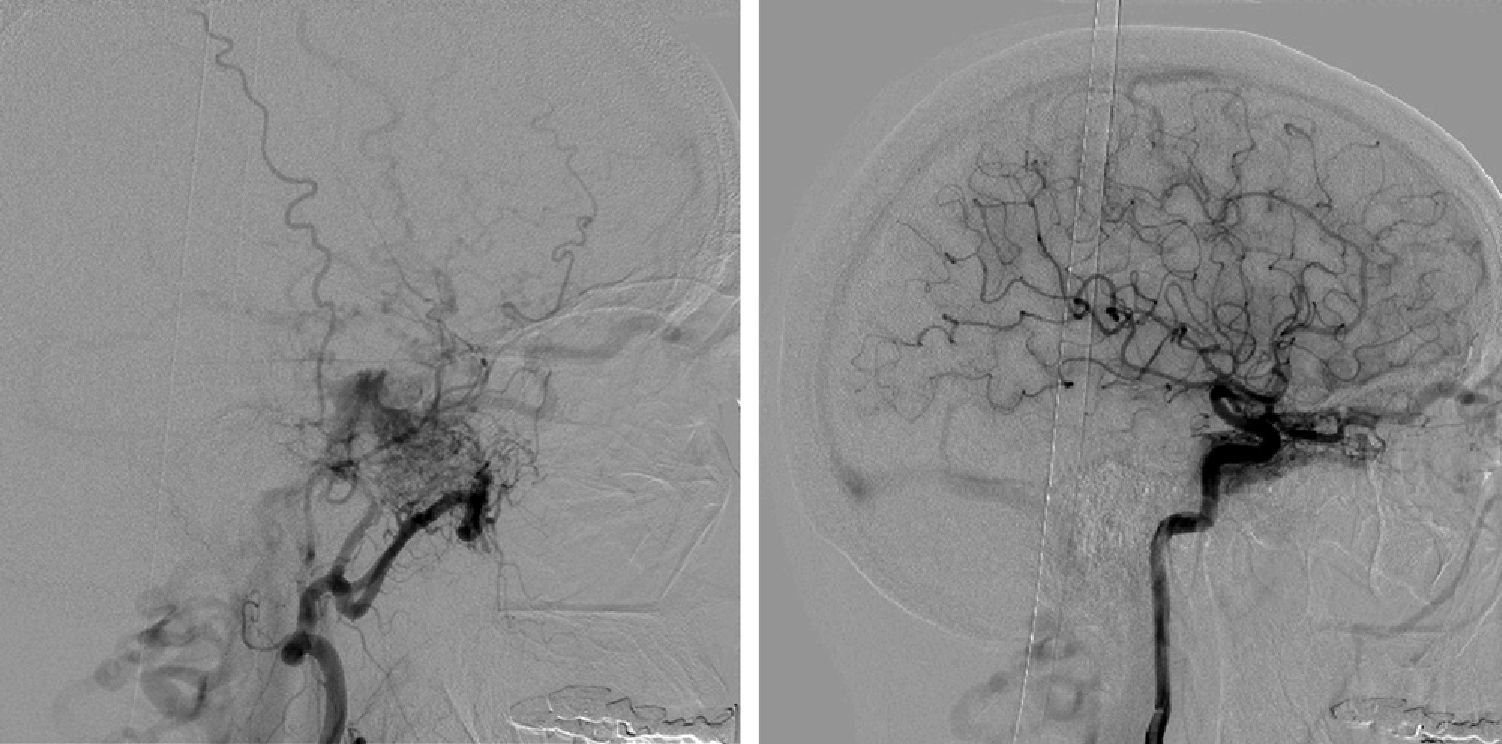

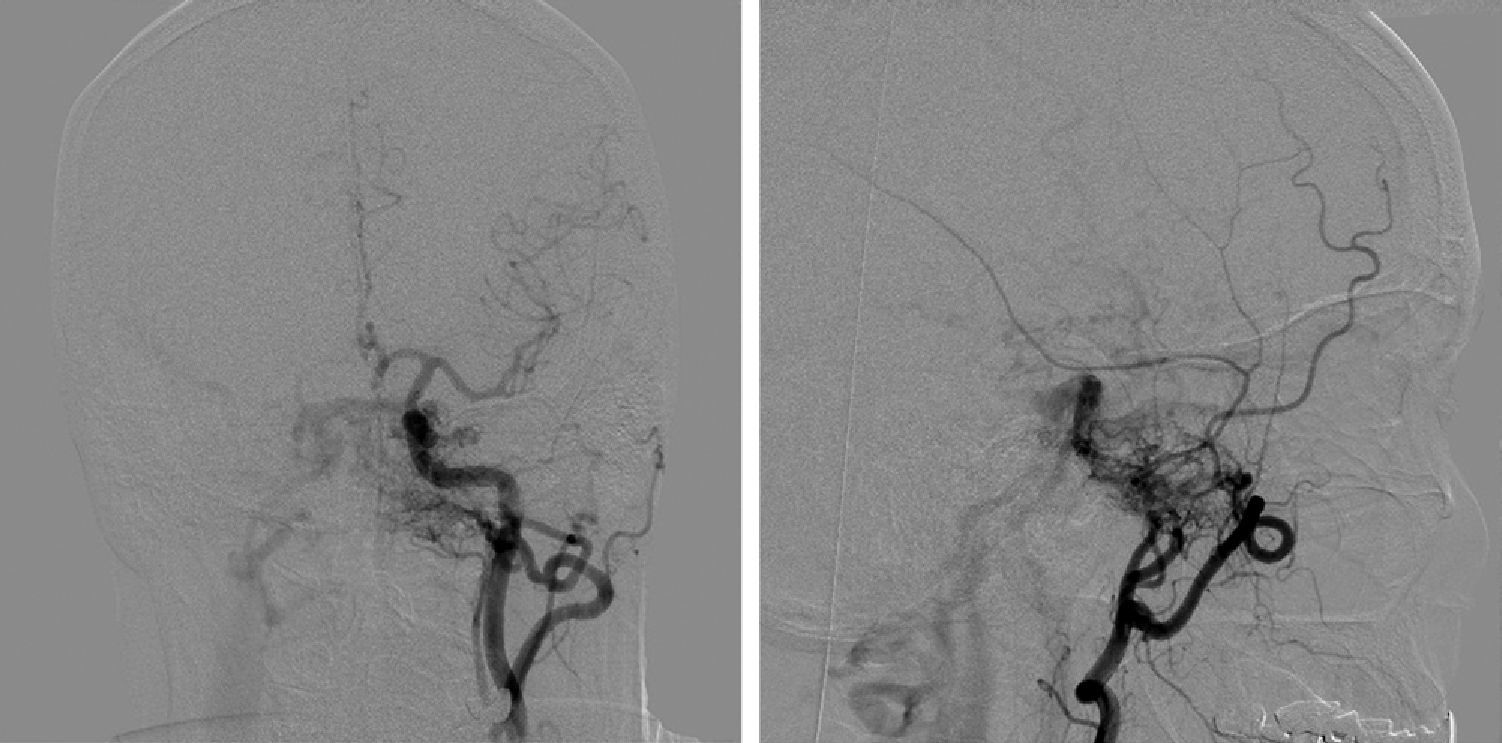

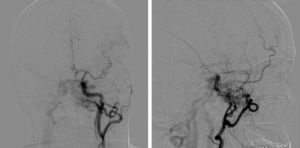

A brain MRI and MRI angiography revealed discrete right-sided exophthalmos, changes in signal intensity in the right cavernous sinus, and an increase in right ophthalmic vein calibre that suggested a right dural carotid-cavernous fistula. In light of these findings, we performed left and right cerebral carotid angiographies which revealed extensive dural fistulous connection affecting the right cavernous and coronary sinuses and probably also the medial margin of the left cavernous sinus. There was a prominent arterial supply from branches of both internal maxillary arteries and also from the inferolateral trunks of both internal carotid arteries. Venous drainage for the fistula followed an anterograde pattern towards both inferior petrosal sinuses, which were found to be permeable. This coexisted with intense reflux to the right superior ophthalmic vein and the facial vein, with extensive involvement of veins of the right cerebral cortex (Figs. 1 and 2). Based on this evidence, the MR angiography and cerebral angiography pointed to a grade III dural carotid-cavernous fistula (with direct drainage to right-sided cortical veins and no ectasia).

Left: Right external carotid artery angiogram, lateral projection, with blood supply from the internal maxillary artery to the cavernous sinus. Right: Lateral projection angiogram of the right internal carotid artery showing blood supply to the cavernous sinus. Both images show the co-presence of reflux to the right ophthalmic vein and facial veins, with extensive participation by right-sided cerebral cortical veins.

Left: Anteroposterior projection angiogram of the left common carotid artery with blood supply to the cavernous sinus from the internal maxillary artery and the inferolateral trunk of the internal carotid. Right: Left external carotid artery angiogram, lateral projection, with blood supply from the internal maxillary artery to the cavernous sinus.

In a second intervention, doctors embolised the cavernous sinus. Subsequent image series of both carotid arteries showed absence of pathological arteriovenous shunting and normalisation of cerebral blood flow in both carotid territories. At 5 months post-intervention, the patient had experienced no further headaches.

Our patient initially presented with a recurrent headache which met criteria for cluster headache. Nevertheless, other data were atypical, such as recent onset in an elderly woman and the association with trigeminal neuralgia with no trigger points or factors. Coexistence of a cluster headache and trigeminal neuralgia was described years ago under the name of cluster tic syndrome. This entity is recognised by the IHS International Headache Classification.6 The primary form of this entity was ruled out by the appearance of oculomotor palsy and findings from complementary tests. The literature has described secondary causes of cluster tic syndrome, including basilar artery ectasia or pituitary adenoma.7,8

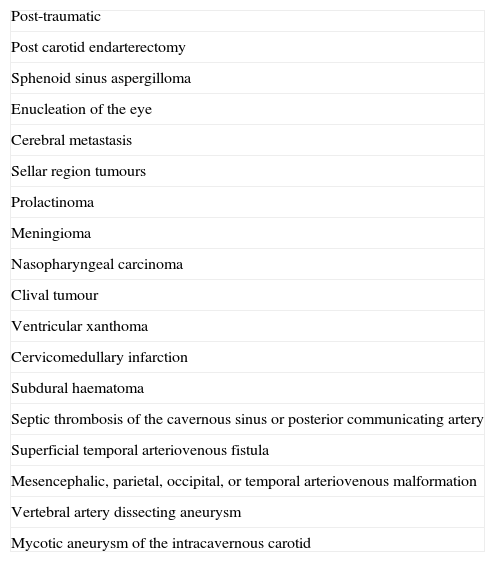

Although the literature does describe dural arteriovenous fistula in association with intermittent headache, we find few descriptions of the clinical characteristics in such cases.4,5 Another noteworthy feature in our case was the fact that the initial brain MRI was normal. On this basis, we advise using MR angiography or a similar technique when studying trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. This complementary test can be used to identify numerous vascular conditions that are known causes of secondary cluster headaches (Table 1).9–12

Aetiology of secondary cluster headaches.

| Post-traumatic |

| Post carotid endarterectomy |

| Sphenoid sinus aspergilloma |

| Enucleation of the eye |

| Cerebral metastasis |

| Sellar region tumours |

| Prolactinoma |

| Meningioma |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| Clival tumour |

| Ventricular xanthoma |

| Cervicomedullary infarction |

| Subdural haematoma |

| Septic thrombosis of the cavernous sinus or posterior communicating artery |

| Superficial temporal arteriovenous fistula |

| Mesencephalic, parietal, occipital, or temporal arteriovenous malformation |

| Vertebral artery dissecting aneurysm |

| Mycotic aneurysm of the intracavernous carotid |

In conclusion, when a patient presents an atypical form of trigeminal autonomic headache, doctors must search for a secondary cause. These headaches are often associated with a wide range of entities, some of which may be quite severe.

Please cite this article as: Payán Ortiz M, Guardado Santervás P, Arjona Padillo A, Aguilera Del Moral A. Clúster-tic como comienzo clínico de una fístula dural carótido cavernosa. Neurología. 2014;29:125–128.