Chorea as a complication of cardiopulmonary surgery associated with extracorporeal circulation (ECC) and hypothermia has classically been reported in children,1 with few cases reported in adults.

We present the case of a 75-year-old man who developed encephalopathy with generalised chorea after aortic valve replacement surgery and coronary revascularisation. Surgery was performed under mild hypothermia (30–32°C), with an ECC time of 193min and aortic clamping lasting 140min. During the postoperative period, the patient did not recover consciousness. A brain CT scan performed at 24hours showed no focal ischaemic or haemorrhagic lesions, and an electroencephalography showed a delta pattern compatible with hypoxic encephalopathy. One week after surgery, he began to present choreoathetosis affecting the face, tongue, neck, trunk, and limbs during episodes of disorientation (). A brain MRI performed 5 days after onset of chorea revealed hyperintense punctiform lesions to the basal ganglia in T2-weighted images, with no restriction detected on diffusion sequences. No significant results were observed in the laboratory analysis, which included copper metabolism, blood smear, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, kidney function, thyroid hormones, and anti-streptolysin O antibodies. We ruled out previous use of neuroleptics or other dopamine receptor-blocking agents. Encephalopathy resolved, but chorea persisted. Symptomatic treatment included haloperidol dosed at 5mg/8h, and amantadine at 200mg/day was added after 4 days. No improvement was observed and treatment was replaced by progressive doses of tetrabenazine of up to 62.5mg/day, with complete remission at 48hours. Doses were gradually decreased, and fully suspended at 2 weeks. Six weeks after surgery, the patient remained asymptomatic without treatment ().

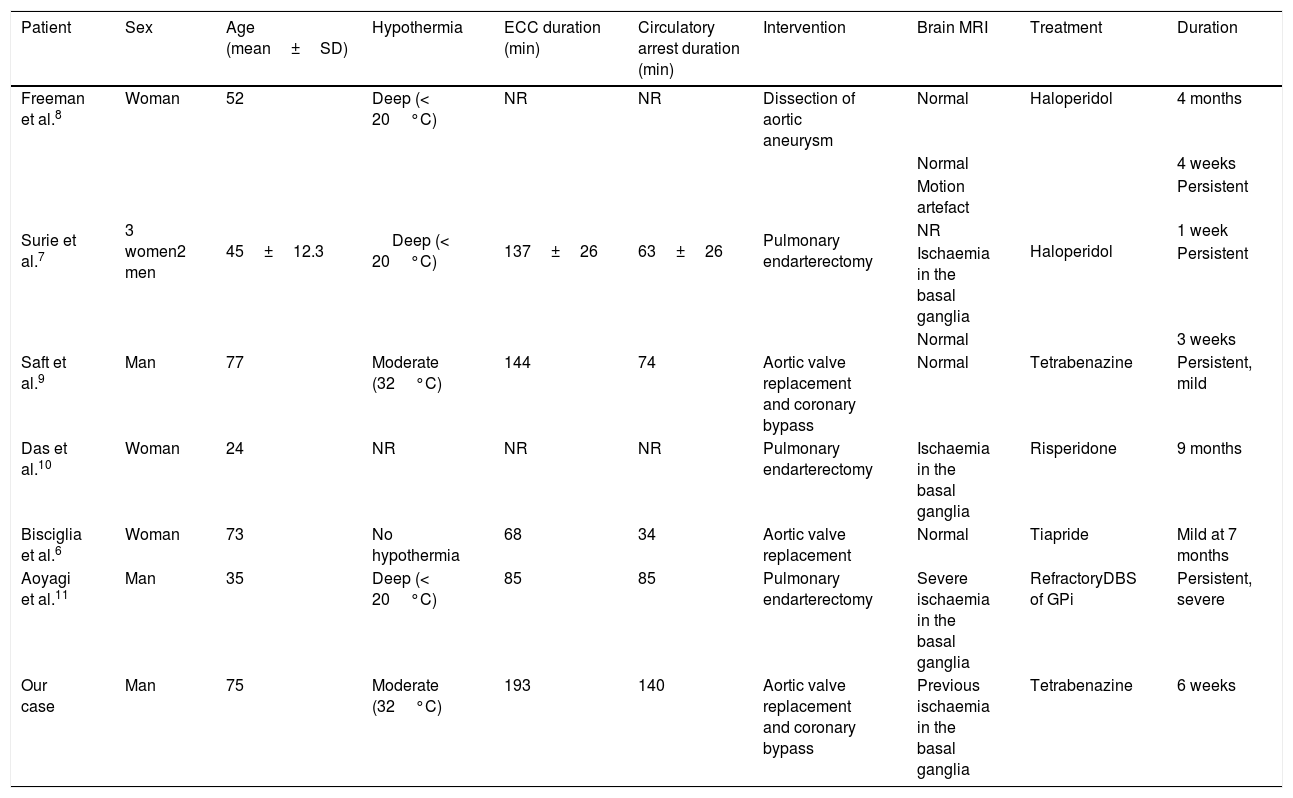

Chorea after ECC is a rare complication of open-heart surgery, and is classically described in children with congenital heart disease. Incidence ranges from 1% to 18%,2,3 and has decreased thanks to surgical and anaesthetic advances that have improved brain perfusion during these procedures. Symptoms may include generalised chorea, dysphagia, dysarthria, and hypotonia, which typically start 3 to 12 days after the procedure; symptoms are transient in half of cases.4 According to the experience with children, duration of circulatory arrest (aortic clamping),2 ECC time,3 prolonged periods of deep hypothermia (< 20°C),2,3 alpha-stat pH strategy,5 and history of cyanosis or developmental delay3,5 have been proposed as risk factors. Medlock et al.2 proposed a significant association between circulatory arrest time, deep hypothermia, and chorea after ECC; however, cases have been reported in both children4 and adults6 without this association. In adults, the literature mainly includes isolated clinical case reports (Table 1).6–11 The study by Surie et al.7 reported a series of 5 cases of chorea after ECC out of a total of 106 patients undergoing pulmonary endarterectomy; chorea was associated with the duration of the circulatory arrest and the rate of rewarming after hypothermia. Adults generally recover after a period of weeks or months. However, in some cases,7,11 symptoms persist and cases have even been described in which patients required deep brain stimulation of the internal globus pallidus (GPi). The presence of new ischaemic lesions in the basal nuclei on MRI sequences may be associated with poorer prognosis, which is more related to vascular chorea. The pathophysiological mechanisms causing chorea after ECC remain unknown. Hypoxia/ischaemia associated with decreased brain circulation during surgery has been suggested as a possible mechanism2,3; this would favour reversible damage to the basal ganglia, with the GPi being especially vulnerable.12 Decreased inhibition of the thalamo-cortical radiations by the GPi would favour a hyperkinetic disorder. This transient dysfunction of the basal nuclei has been demonstrated by alterations in brain FDG-PET scans and somatosensory evoked potential studies.9 The association between chorea and abnormal somatosensory evoked potential study findings have previously been described in Huntington disease.13 In addition to the hypoxia/ischaemia theory, another hypothesis has been proposed that considers chorea after ECC as a form of acquired neuroacanthocytosis secondary to the mechanical trauma to erythrocytes during ECC.14

Summary of published clinical cases of chorea after extracorporeal circulation.

| Patient | Sex | Age (mean±SD) | Hypothermia | ECC duration (min) | Circulatory arrest duration (min) | Intervention | Brain MRI | Treatment | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freeman et al.8 | Woman | 52 | Deep (< 20°C) | NR | NR | Dissection of aortic aneurysm | Normal | Haloperidol | 4 months |

| Surie et al.7 | 3 women2 men | 45±12.3 | Deep (< 20°C) | 137±26 | 63±26 | Pulmonary endarterectomy | Normal | Haloperidol | 4 weeks |

| Motion artefact | Persistent | ||||||||

| NR | 1 week | ||||||||

| Ischaemia in the basal ganglia | Persistent | ||||||||

| Normal | 3 weeks | ||||||||

| Saft et al.9 | Man | 77 | Moderate (32°C) | 144 | 74 | Aortic valve replacement and coronary bypass | Normal | Tetrabenazine | Persistent, mild |

| Das et al.10 | Woman | 24 | NR | NR | NR | Pulmonary endarterectomy | Ischaemia in the basal ganglia | Risperidone | 9 months |

| Bisciglia et al.6 | Woman | 73 | No hypothermia | 68 | 34 | Aortic valve replacement | Normal | Tiapride | Mild at 7 months |

| Aoyagi et al.11 | Man | 35 | Deep (< 20°C) | 85 | 85 | Pulmonary endarterectomy | Severe ischaemia in the basal ganglia | RefractoryDBS of GPi | Persistent, severe |

| Our case | Man | 75 | Moderate (32°C) | 193 | 140 | Aortic valve replacement and coronary bypass | Previous ischaemia in the basal ganglia | Tetrabenazine | 6 weeks |

DBS: deep brain stimulation; ECC: extracorporeal circulation; GPi: internal globus pallidus; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NR: not reported; SD: standard deviation.

In short, chorea after ECC is an infrequent complication of cardiopulmonary surgery caused by unknown mechanisms. Neuroleptics and tetrabenazine improve symptoms, and prognosis is generally favourable in the absence of new ischaemic lesions.

Please cite this article as: Máñez Miró JU, Vivancos Matellano F. Corea tras circulación extracorpórea en adultos: breve revisión a propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2020;35:519–521.