The increase in such age-related diseases as age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) is causing higher incidence of Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS), which consists of visual hallucinations in patients with preserved cognitive status.1 CBS has been associated with systemic diseases2–4 and topical5 and systemic6,7 treatments. We present a case of CBS triggered by a hypertensive crisis, which was self-limiting with monitoring of arterial pressure at the emergency department.

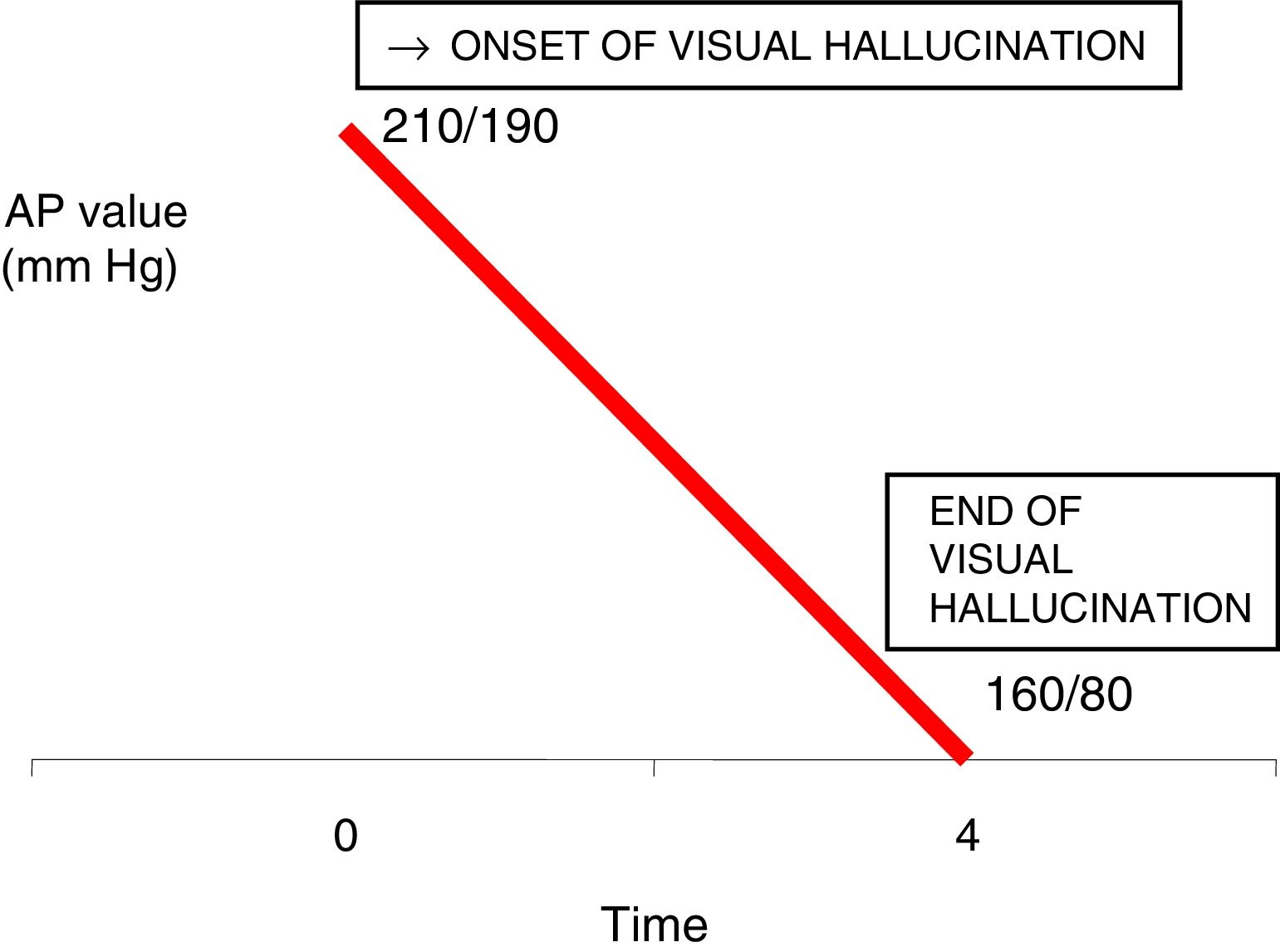

Our patient is an 85-year-old man who attended a private consultation due to a first known episode of hypertensive crisis accompanied by visual alterations. His personal history included atrophic ARMD in both eyes (OU), diagnosed 5 years previously; arterial hypertension (AHT), which had been treated with losartan (50mg daily) for 10 years, although treatment was not strictly followed; and type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with diet for 3 years. During the examination, the patient presented arterial pressure (AP) values of 210/190mmHg, then reported seeing several unknown people who did not speak. Hallucinations featured colour and movement. Although the patient knew they were not real, he was alarmed by the fact that he could see them clearly despite his poor vision. He also presented holocranial headache, a sensation of palpitations, and epistaxis as the only accompanying symptoms. No seizures or any other neurological manifestations were observed during the episode. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed no other alterations. The patient was given 2 oral doses of 50mg captocapril separated by 30min to control AP. With the progressive control of AP, the visual hallucinations started to progressively decrease also in number and frequency, disappearing completely 4hours after symptom onset; AP was 160/80mmHg at that time (Fig. 1).

He was transferred to our hospital's neuro-ophthalmology department; during the ophthalmological examination, he was able to count fingers at 1metre with OU. Intraocular pressure was 16mmHg in OU. Biomicroscopy yielded normal results and eye fundus examination revealed atrophic ARMD. As other causes of hallucinations were ruled out, the patient was diagnosed with CBS secondary to hypertensive crisis.

The origin of the hallucinations in CBS is unknown, although deafferentiation is thought to be a possible trigger factor for these hallucinations.8–10 According to this theory, since the occipital cortical area receives fewer afferences from the pathological retina, or due to different eye diseases, this compensatory phenomenon would occur in those deafferentiated areas, which would become hyperexcitable before any stimulus.8–10

Development of hallucinations has been associated with such trigger factors as flash blindness or dim lighting,7 systemic7 and surgical11 eye treatments,5,6 and such systemic diseases as anaemia,2 occipital infarcts,3 or multiple sclerosis.4

In our case, the hypertensive crisis would cause a series of reversible functional changes to the deafferentiated cortical areas, which would trigger visual hallucinations. Sustained high AP would cause haemodynamic, chemical, and histological alterations, which would act as trigger factors for visual hallucinations in the occipital cortex. The mechanism would be alteration of the cortical tissue due to high AP in the blood vessel maintaining haemodynamics in these areas. Deafferentiated neurons would be stimulable in this case by hypertension in the cerebral blood vessels corresponding to these cortical areas; with administration of a hypotensive treatment and monitoring of the hypertensive crisis, stimuli and trigger factors disappeared, the episode resolved, and the deafferentiated cortex stabilised.

Please cite this article as: Cifuentes-Canorea P, Cerván-López I, Rodríguez-Uña I, Santos-Bueso E. Síndrome de Charles Bonnet secundario a crisis hipertensiva. Neurología. 2018;33:473–474.