Cavernous sinus syndrome (CSS) is defined by involvement of 2 or more of the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth cranial nerves secondary to inflammation or a space-occupying lesion in the cavernous sinus.1 The typical clinical presentation includes periorbital pain, ptosis, headache, diplopia, ophthalmoplegia, and visual alterations.2–4 The most frequent causes include tumours (nasopharyngeal carcinoma, meningioma, lymphoma, and metastases), vascular disease (aneurysms, fistulas, and thrombosis), and inflammatory disease (Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, IgG4-related disease, sarcoidosis, vasculitis). Although less frequent, risk populations especially present infectious diseases (tuberculosis, Haemophilus influenzae septic thrombophlebitis, neurosyphilis, or mucormycosis in diabetic patients). Exceptionally, CSS may be associated with invasive aspergillosis, as in the case we present.

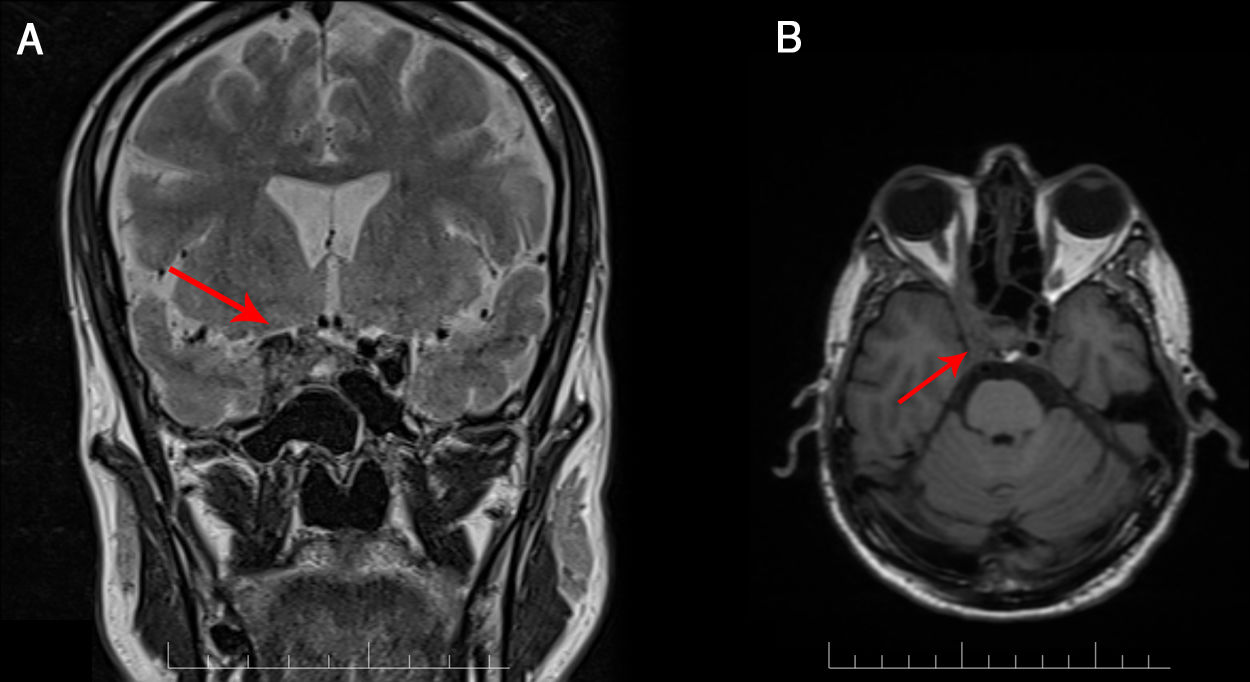

We present the case of a 49-year-old man with history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and category C3 HIV infection (CD4 count of 140 cells/mm3), diagnosed 3 months prior to admission. He was receiving regular treatment with bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide. The patient reported right frontoparietal headache of 6 months’ progression, which led to several visits to the emergency department, where a head computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, revealing no alterations. He progressively developed diplopia and photophobia. The neurological examination revealed fluctuating ptosis, hyporeactive mydriatic pupil, and diplopia in all directions of gaze, with limited infralevoversion, levoversion, and supraversion, all involving the right eye. No meningeal signs or fever were observed. A brain MRI study revealed a contrast-enhancing mass in the right cavernous sinus, extending to the orbital apex and affecting the wall of the right internal carotid artery (Fig. 1). A routine biochemical analysis and blood count detected no relevant abnormalities. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed no red blood cells, 3 nucleated cells, lactate level of 8.8 mmol/L, protein level of 0.37 g/L, and glucose level of 0.47 g/L; adenosine deaminase levels were normal. A chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT scan revealed no pathological findings. Serology for toxoplasma, syphilis, and Borrelia, and a PCR test for cytomegalovirus yielded negative results. Gram staining and CSF culture for bacteria and mycobacteria also returned negative results. Testing for the galactomannan antigen and (1-3)-β-d-glucan and PCR test for Aspergillus yielded negative results in serum and CSF. PCR testing did not detect Pneumocystis jirovecci, Cryptococcus neoformans, or Histoplasma capsulatum in the CSF. A biopsy specimen of the lesion was obtained through the endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach. Gram staining, cultures, and PCR testing of the specimen yielded negative results for fungi and bacteria. A histological analysis revealed an inflammatory lesion with abundant histiocytes, neutrophils, and fungal colonies suggestive of Aspergillus spp. Based on the anatomical pathology results, we collected a sample to repeat the PCR test, which finally yielded positive results for Aspergillus spp. We administered a 2-week course of intravenous antifungal treatment with voriconazole at 6 mg/kg every 12 hours during the first day, followed by 4 mg/kg every 12 hours and liposomal amphotericin B at 4 mg/kg every 24 hours. Amphotericin was switched for intravenous caspofungin at 50 mg/kg due to impaired renal function and hyponatraemia. Voriconazole was suspended after 10 days due to hepatotoxicity, and we started oral posaconazole at 300 mg daily at discharge. Antiretroviral therapy was not modified. At a 5-month follow-up visit, we observed good clinical progression, with the patient being asymptomatic. From a radiological viewpoint, the patient was stable, with the follow-up MRI scan showing no changes.

The literature on cavernous sinus syndrome in patients with HIV infection is limited to small case series and isolated case reports. In this subgroup, the infectious disease most frequently affecting the cavernous sinus is tuberculosis, followed by neurosyphilis, with cryptococcosis and aspergillosis being anecdotal1. Furthermore, it is important to rule out oncological diseases, including HIV-associated lymphoma.5,6

Aspergillus fumigatus is the most frequent cause of aspergillosis in humans. Although it mainly affects immunocompromised patients, its incidence is low in patients with HIV, and is usually limited to those with a CD4 cell count below 100 cells/mm3. In 80% of cases of invasive aspergillosis in patients with HIV infection, the lesion is located in the lungs; involvement of the cavernous sinus is rarely reported.7–9 Brain MRI is the most useful tool for diagnosing the condition, although a definitive diagnosis is not always reached.1,10 Cavernous sinus involvement is typically characterised by heterogeneous, hypointense lesions on T1- and T2-weighted sequences, as well as a tendency to invade nearby vessels, as in our case, in which we observed involvement of the internal carotid artery (Fig. 2).11–13 Laboratory tests are usually inconclusive.14 Testing for galactomannan antigen and (1-3)-β-d-glucan in the serum and PCR testing for Aspergillus are useful tools, although sensitivity may be affected in cases with sinus involvement.9 In our case, the first PCR test of the biopsy specimen yielded negative results; therefore, obtaining a specimen for histological analysis was essential for management and definitive diagnosis. However, collection of the specimen was limited by the patient’s clinical status and the delicate anatomical location.

In short, invasive aspergillosis of the cavernous sinus is a rare and difficult-to-diagnose condition that should be considered in immunocompromised patients. Imaging and laboratory studies are frequently inconclusive; therefore, we should obtain biopsy specimens of the lesion where possible. Management of these patients requires a multidisciplinary approach involving neurologists, internists, neurosurgeons, radiologists, and pathologists.

Please cite this article as: Saldaña Inda I, Sancho Saldaña A, García Rubio S, Sagarra Mur D. Síndrome de seno cavernoso secundario a aspergilosis invasiva con afectación carotídea en paciente VIH. Neurología. 2021;36:552–554.