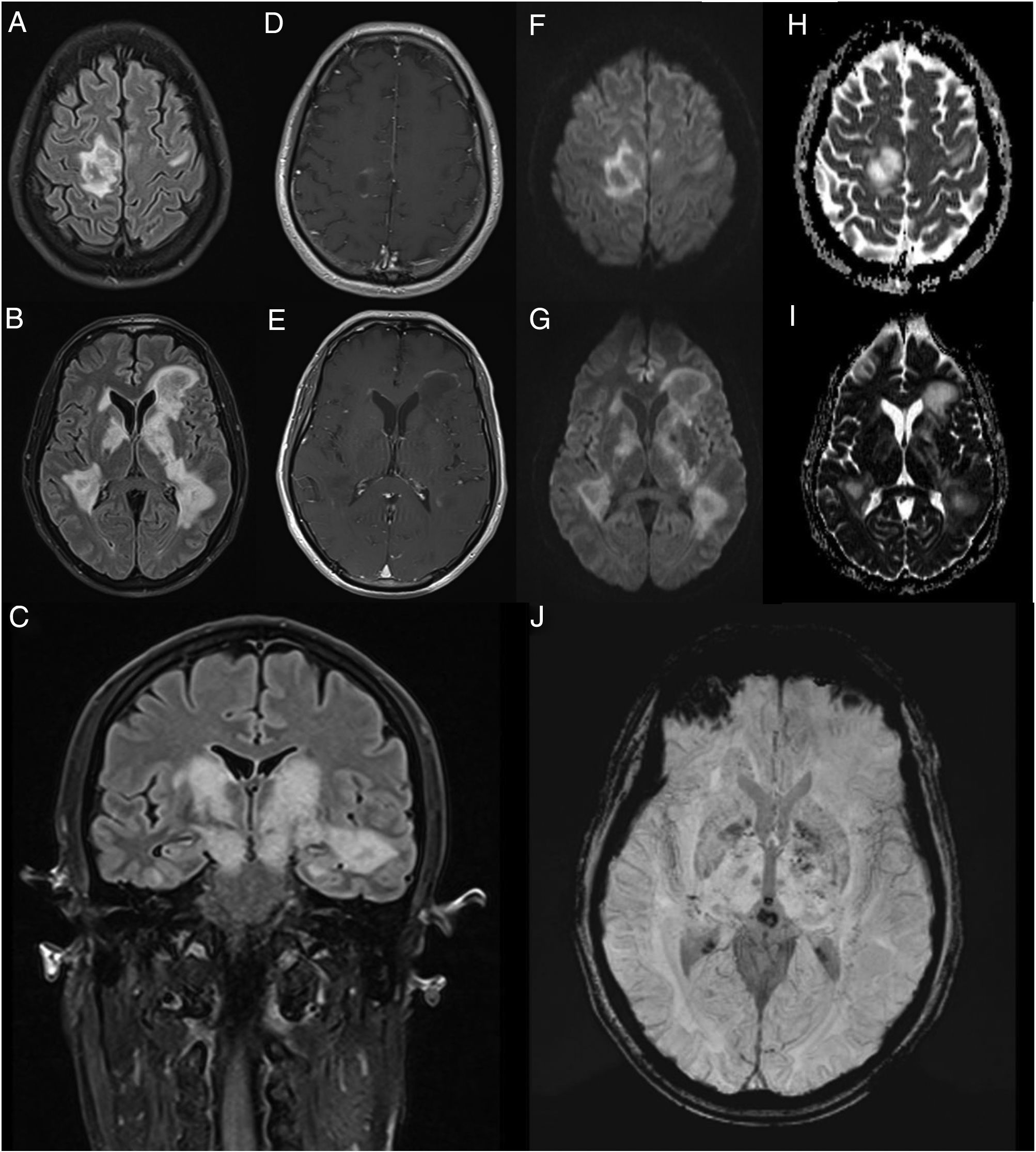

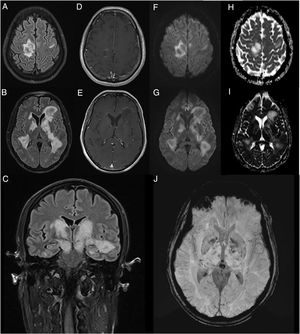

We present the case of a 45-year-old man with no relevant medical history who consulted due to one week’s history of progressive encephalopathy and faciobrachicrural hemiparesis. He reported no history of infection, recent vaccination, toxic habits, constitutional symptoms, or any other relevant alterations. A contrast-enhanced brain MRI scan revealed multiple T2-hyperintense nodular lesions in both hemispheres; the lesions involved the corticosubcortical junction, basal ganglia, and brainstem, with no significant perilesional oedema or mass effect. Only one lesion showed contrast uptake. These findings led us to suspect infection or tumour; however, these diagnostic hypotheses were ruled out after comprehensive serology testing and cerebrospinal fluid analysis and a chest and abdomen CT scan, which yielded normal results. An autoimmunity study revealed presence of oligoclonal bands, although the patient tested negative for anti-AQP4 and anti-MOG antibodies. The study also revealed low titres of antinuclear and antithyroid antibodies. Hormone and vitamin profile tests yielded normal results, and a toxicology screening test yielded negative results. An additional brain MRI scan revealed increased lesion extension, associated with mild diffusion restriction and open-ring enhancement, as well as petechial haemorrhages on susceptibility-weighted images (Fig. 1). A contrast-enhanced spinal cord MRI scan detected no alterations. Due to suspicion of an autoimmune inflammatory process of the CNS, we initially prescribed a 5-day course of 1 g intravenous methylprednisolone. However, symptoms progressed in the following weeks; the patient presented impaired consciousness, and was admitted to the intensive care unit. During his stay at the unit, he presented signs suggestive of epilepsy; this was confirmed by an EEG study, which revealed frequent interictal epileptiform discharges in the right frontal lobe. Another contrast-enhanced brain and spinal cord MRI scan did not reveal any significant changes that may explain the clinical worsening. The patient received 5 sessions of plasmapheresis on alternating days, together with an additional course of 1 g intravenous methylprednisolone for 5 days, with no clinical improvement. He was then administered 2 rituximab infusions (body surface area–based dosing), presenting marked clinical and radiological improvement. After 11 months of follow-up, with no immunosuppressant treatment, the patient has presented no relapses or new inflammatory lesions on follow-up brain and spinal cord MRI scans, and his functional status has improved, with partial independence in daily living activities.

Contrast-enhanced brain MRI (A-B and D-J: axial plane; C: coronal plane). Multiple parenchymal pseudonodular lesions in both hemispheres, hyperintense on FLAIR sequences (A-C), mainly affecting the periventricular and juxtacortical white matter of the right precentral gyrus, the basal ganglia, and the internal capsule, extending caudally to the cerebral peduncles in the midbrain. The lesions are not associated with significant oedema or mass effect. Some present mild open-ring contrast uptake following gadolinium administration (D-E), with mild diffusion restriction (diffusion-weighted imaging: F-G; apparent diffusion coefficient: H-I). Deeper lesions present petechial foci on susceptibility-weighted imaging sequences (J).

The radiological characteristics of the lesions and the patient’s clinical progression and response to third-line immunotherapy with rituximab are compatible with fulminant multifocal demyelinating encephalitis.

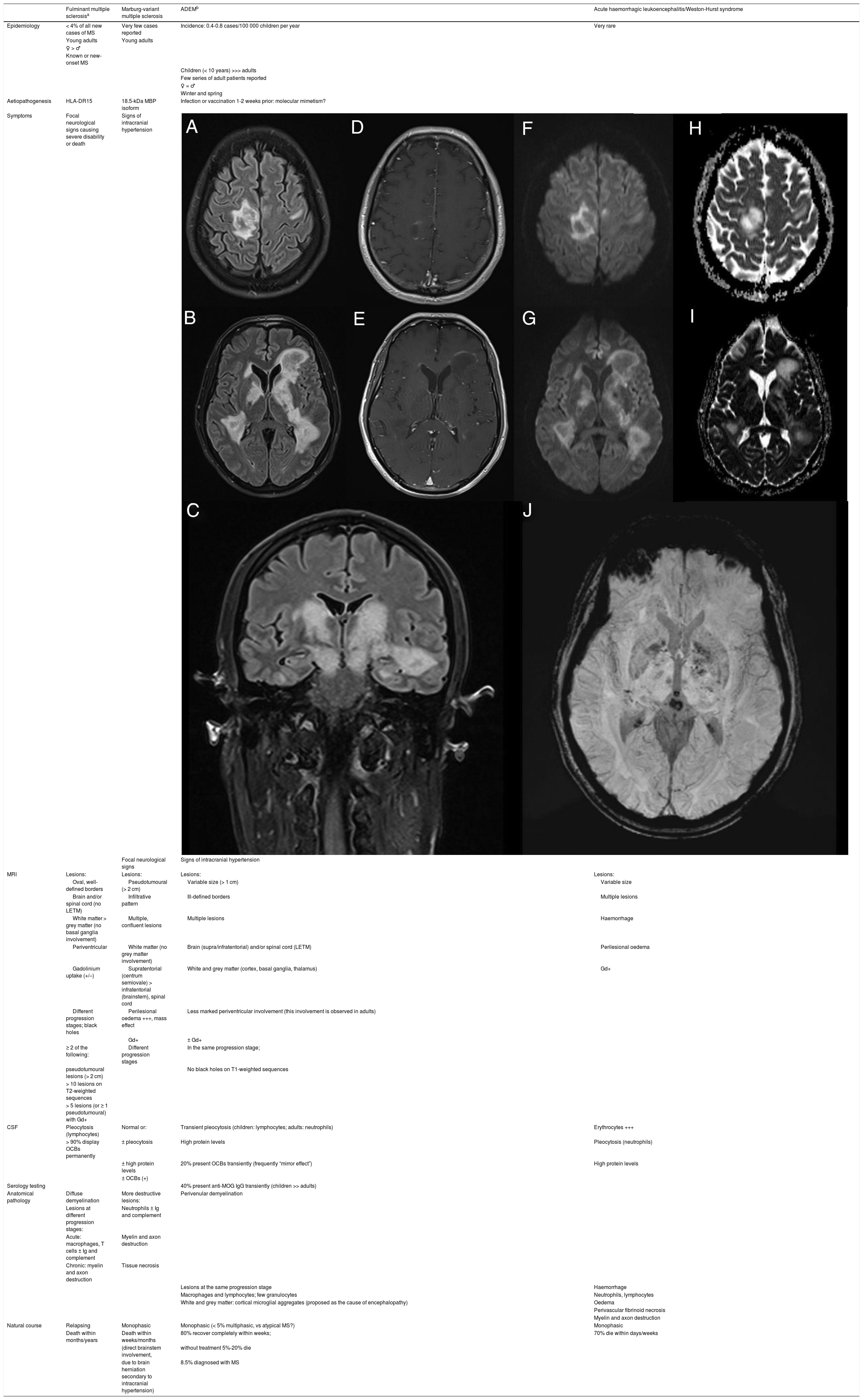

Fulminant demyelinating diseases of the CNS are a group of extremely rare autoimmune diseases that often lead to the patient’s death due to an uncontrolled immune response and the critical localisation (eg, brainstem) and extension of the lesions; when lesions are larger than 2 cm in diameter, they are described as pseudotumoural due to their clinico-radiological behaviour, which resembles that of brain tumours.1,2 These entities are thought to be closely related to multiple sclerosis; however, we are still unable to identify those patients who, after a first episode of severe demyelination, present greater risk of developing a recurrent form of demyelinating disease of the CNS.1 The available information on these conditions is inconsistent, given their low frequency and the overlap between them.2,3 Only a few have been defined with widely accepted diagnostic criteria, as is the case with fulminant multiple sclerosis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders.3Table 1 presents the clinical, radiological, laboratory, and anatomical pathology characteristics of the main entities included in the differential diagnosis of our case; the patient presented features of several of these conditions, demonstrating the overlap between them.1–7

Clinical, radiological, laboratory, and anatomical pathology characteristics of the 4 main fulminant demyelinating diseases of the CNS included in the differential diagnosis of our patient.

| Fulminant multiple sclerosisa | Marburg-variant multiple sclerosis | ADEMb | Acute haemorrhagic leukoencephalitis/Weston-Hurst syndrome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | < 4% of all new cases of MS | Very few cases reported | Incidence: 0.4-0.8 cases/100 000 children per year | Very rare |

| Young adults | Young adults | |||

| ♀ > ♂ | ||||

| Known or new-onset MS | ||||

| Children (< 10 years) >>> adults | ||||

| Few series of adult patients reported | ||||

| ♀ = ♂ | ||||

| Winter and spring | ||||

| Aetiopathogenesis | HLA-DR15 | 18.5-kDa MBP isoform | Infection or vaccination 1-2 weeks prior: molecular mimetism? | |

| Symptoms | Focal neurological signs causing severe disability or death | Signs of intracranial hypertension | ||

| Focal neurological signs | Signs of intracranial hypertension | |||

| MRI | Lesions: | Lesions: | Lesions: | Lesions: |

| Oval, well-defined borders | Pseudotumoural (> 2 cm) | Variable size (> 1 cm) | Variable size | |

| Brain and/or spinal cord (no LETM) | Infiltrative pattern | Ill-defined borders | Multiple lesions | |

| White matter > grey matter (no basal ganglia involvement) | Multiple, confluent lesions | Multiple lesions | Haemorrhage | |

| Periventricular | White matter (no grey matter involvement) | Brain (supra/infratentorial) and/or spinal cord (LETM) | Perilesional oedema | |

| Gadolinium uptake (+/–) | Supratentorial (centrum semiovale) > infratentorial (brainstem), spinal cord | White and grey matter (cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus) | Gd+ | |

| Different progression stages; black holes | Perilesional oedema +++, mass effect | Less marked periventricular involvement (this involvement is observed in adults) | ||

| Gd+ | ± Gd+ | |||

| ≥ 2 of the following: | Different progression stages | In the same progression stage; | ||

| pseudotumoural lesions (> 2 cm) | No black holes on T1-weighted sequences | |||

| > 10 lesions on T2-weighted sequences | ||||

| > 5 lesions (or ≥ 1 pseudotumoural) with Gd+ | ||||

| CSF | Pleocytosis (lymphocytes) | Normal or: | Transient pleocytosis (children: lymphocytes; adults: neutrophils) | Erythrocytes +++ |

| > 90% display OCBs permanently | ± pleocytosis | High protein levels | Pleocytosis (neutrophils) | |

| ± high protein levels | 20% present OCBs transiently (frequently “mirror effect”) | High protein levels | ||

| ± OCBs (+) | ||||

| Serology testing | 40% present anti-MOG IgG transiently (children >> adults) | |||

| Anatomical pathology | Diffuse demyelination | More destructive lesions: | Perivenular demyelination | |

| Lesions at different progression stages: | Neutrophils ± Ig and complement | |||

| Acute: macrophages, T cells ± Ig and complement | Myelin and axon destruction | |||

| Chronic: myelin and axon destruction | Tissue necrosis | |||

| Lesions at the same progression stage | Haemorrhage | |||

| Macrophages and lymphocytes; few granulocytes | Neutrophils, lymphocytes | |||

| White and grey matter: cortical microglial aggregates (proposed as the cause of encephalopathy) | Oedema | |||

| Perivascular fibrinoid necrosis | ||||

| Myelin and axon destruction | ||||

| Natural course | Relapsing | Monophasic | Monophasic (< 5% multiphasic, vs atypical MS?) | Monophasic |

| Death within months/years | Death within weeks/months | 80% recover completely within weeks; | 70% die within days/weeks | |

| (direct brainstem involvement, | without treatment 5%-20% die | |||

| due to brain herniation secondary to intracranial hypertension) | 8.5% diagnosed with MS | |||

ADEM: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; IG: immunoglobulin; IgG: immunoglobulin G; LETM: longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis; MBP: myelin basic protein; MOG: myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MS: multiple sclerosis; OCBs: oligoclonal bands.

Today, the prognosis of these conditions is less disheartening thanks to the widespread use of MRI, which enables earlier diagnosis, and improvements in immunosuppressive and life support treatments.4 Reporting of all cases of fulminant CNS demyelination will increase our understanding of these entities and improve the care provided to these patients.

Please cite this article as: Rubio-Guerra S, Massuet-Vilamajó A, Presas-Rodríguez S, Ramo-Tello C. Encefalitis desmielinizante multifocal catastrófica. Neurología. 2022;37:159–163.