Rare cases have been described of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy due to unilateral hippocampal sclerosis (TLE-HS), presenting epileptiform activity contralateral to the hippocampal atrophy, or with bilateral activity, in the so-called burned-out hippocampus syndrome,1 which presents with false lateralisation of seizure onset and electro-clinico-radiological incongruity and requires invasive evaluation.2,3

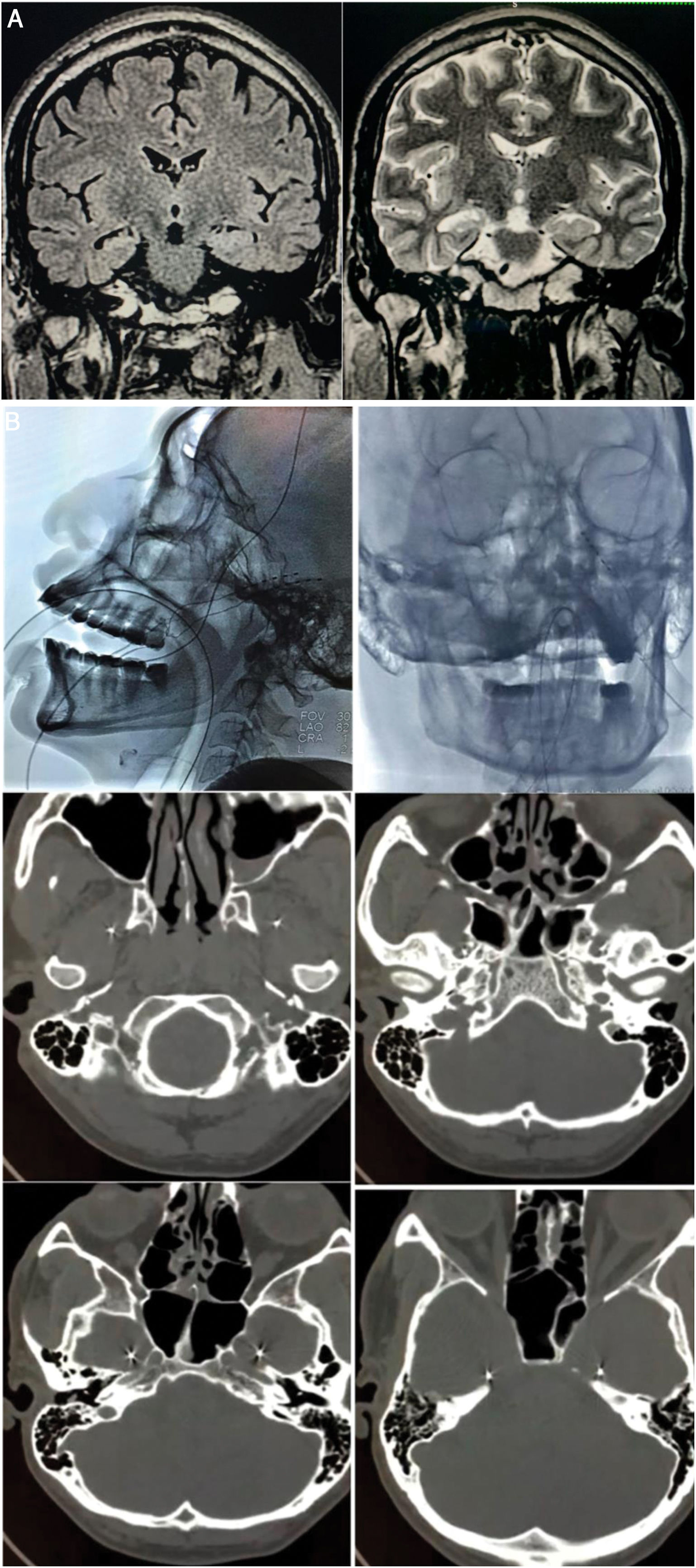

We present the case of a 45-year-old right-handed man with a 12-year history of drug-resistant TLE-HS, who had suffered mild head trauma at the age of 7 years. Seizures presented as a sensation of penetration of thought, an urge to run away, anxiety, disconnection from his setting, and automatisms, with post-ictal confusion; seizure duration was 2 minutes, with a frequency of 2-3 episodes per month. The patient was receiving polytherapy with lacosamide, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, and carbamazepine. Brain MRI revealed right HS (Fig. 1A). Video EEG with surface electrodes (vEEG-s), lasting 96 hours, revealed bilateral temporal interictal epileptiform activity, predominantly in the right hemisphere, and 8 identical ictal events with initially unilateral rhythmic theta waves in the temporal region; onset was left-sided on 6 occasions and right-sided on 2. Neuropsychological evaluation revealed mild to moderate attentional and language impairment, very low intelligence quotient score, and moderate verbal and visuospatial memory impairment. Ictal and interictal SPECT studies were inconclusive. Physical examination revealed anxiety, bradypsychia, and poor short-term memory, with no other abnormalities.

A) Preoperative brain MRI scan (1.5 T). Left: coronal T2-FLAIR sequence showing hyperintensity in the right hippocampus. Right: coronal T2-weighted sequence showing the reduced volume and altered architecture of the right hippocampus. B) Implantation of foramen ovale electrodes (FOE). Top left: antero-posterior fluoroscopy image showing the left FOE. Top right: lateral radiography showing the implanted electrodes. Middle left: infratemporal extracranial position. Middle right: passage through the foramen ovale. Bottom: intracranial localisation in the mesial part of the temporal lobe (ambiens cistern).

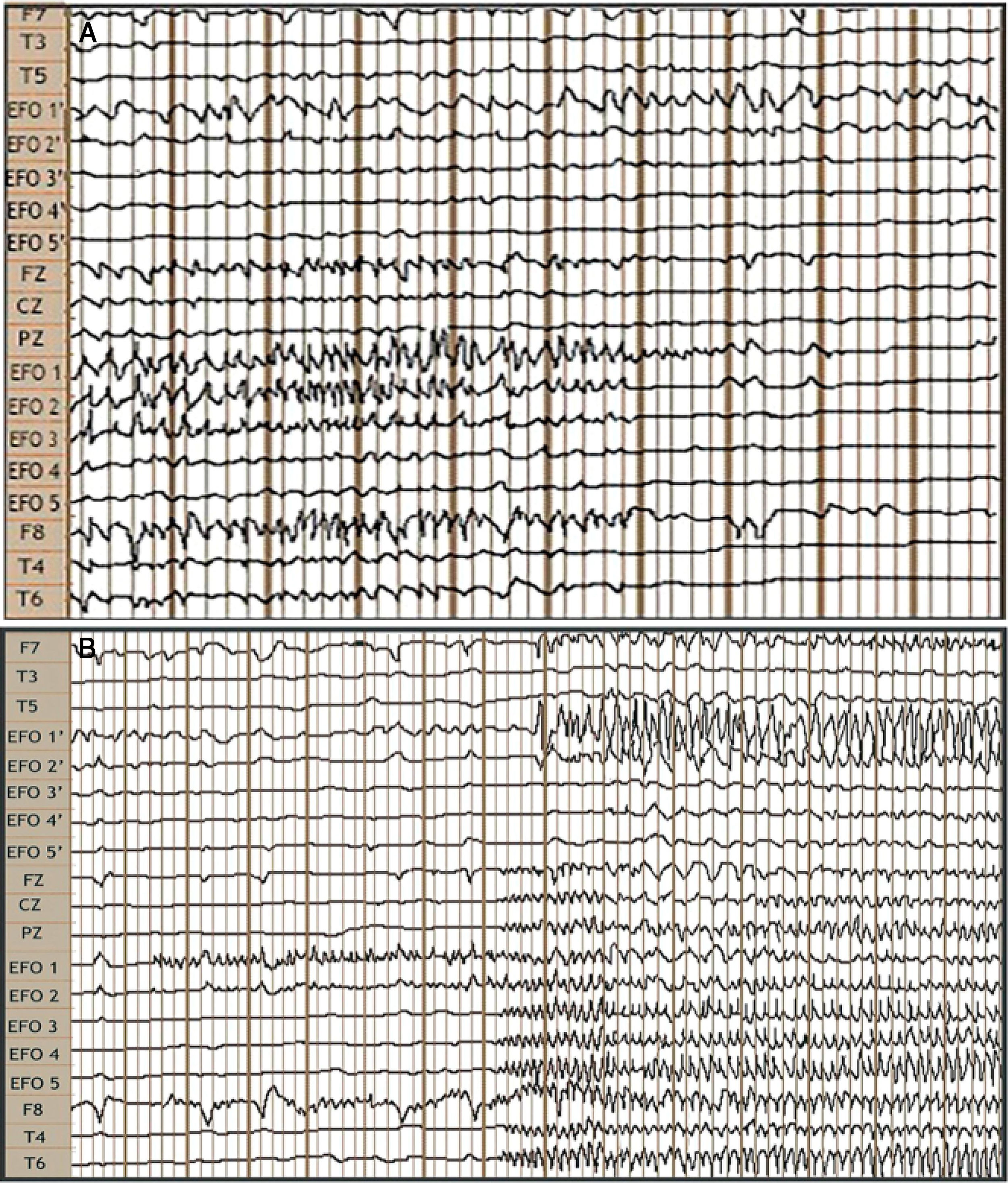

We bilaterally implanted foramen ovale electrodes (FOE; 1 × 5) (Fig. 1B) and performed complementary vEEG-s (reference montage), of 48 hours’ duration. The study detected interictal activity similar to that recorded in previous EEG studies, with 3 electrically identical stereotyped seizures: fast, low-amplitude activity in contacts 1 and 2 of the right FOE, of 7 seconds’ duration, with secondary propagation to contacts 1 and 2 of the left FOE, where amplitude clearly increased, and subsequently to electrodes F8, T4, and T6, with progressive rhythmic theta activity (Fig. 2). These findings confirmed the localisation of the epileptogenic zone in the right hippocampus. In February 2016, we performed a standard anterior temporal lobectomy with right amygdalohippocampectomy; the patient continued receiving carbamazepine in monotherapy. A routine EEG performed in March 2018 showed no epileptiform activity, and antiepileptic treatment was suspended. The patient has remained seizure free (Engel class 1A) to date, and has integrated well into his previous work as a farmer.

Video EEG study: bilateral foramen ovale electrodes (FOE) and complementary surface electrodes: international 10-20 system, left-to-right reference montage. A) Interictal: fast activity with bilateral (predominantly right-sided) spikes of medium voltage. B) Ictal: onset of fast, low-amplitude activity in FOE contacts 1 and 2, lasting 7 seconds, followed by propagation to the contralateral hippocampus, generating greater amplitude, and across the right temporal lobe.

The aetiology of TLE includes such factors as perinatal hypoxia, febrile seizures, brain trauma, and neurological infections,2 and is frequently bilateral4; vEEG-s may show unilateral or synchronised or independent bilateral interictal activity; ictal activity may spread to the contralateral lobe in 30% of cases (only 3%-7.5% in unilateral TLE-HS).2 These bilateral discharges may be interpreted as multifocal epilepsy, with surgical treatment potentially being ruled out as a result.5 Intracranial electrodes show ictal onset in the affected hippocampus with rapid propagation to the contralateral hippocampus; this incongruity indicates false lateralisation.4 Mintzer et al.4 present 5 cases in a sample of 109 patients with TLE who underwent implantation of intracranial electrodes (4.6%), with unilateral hippocampal atrophy in MRI studies and ictal EEG-s recordings showing seizure onset in the contralateral temporal lobe and few or no seizures with ipsilateral onset; this combination of findings is referred to as burned-out hippocampus syndrome. Williamson et al.6 report burned-out hippocampus syndrome in 5 of 67 patients (7.5%). Our research group has identified one case among a total of 13 patients (7.7%).

It has been suggested that the false lateralisation may be explained by severe neuronal loss in the damaged hippocampus, which would render the structure unable to recruit sufficient neocortical neurons, activating the contralateral hippocampus and neocortex via the dorsal hippocampal commissure, registering on EEG-s as ictal discharges contralateral to the atrophied hippocampus.1,2,4,7 Activity is propagated simultaneously to the structurally damaged neocortex, which is unable to radially propagate activity originating in the hippocampus to the surface.5

One predictor of false lateralisation is the presence of interictal activity predominantly ipsilateral to the hippocampal atrophy,4 which, as it originates in the irritative zone (greater size), is able to recruit greater numbers of neurons and to spread to the ipsilateral neocortex; in ictal recordings, high-frequency, low-voltage activity (smaller than that originating in the irritative zone) is of insufficient volume to generate an electric field visible on vEEG-s.5

Diagnostic work-up in cases of suspected burned-out hippocampus syndrome must seek to rule out multifocal onset and confirm false lateralisation with depth electrodes, basal temporal subdural grid electrodes, or such semi-invasive techniques as FOEs.2–4 Ictal/interictal SPECT and PET have been proposed as non-invasive methods that may help to resolve this conflict.4 In our patient, we opted for FOE implantation, a cost-effective technique given its low cost, reduced complexity, good safety, and optimal accuracy.8–10

Up to 80% of patients with burned-out hippocampus syndrome achieve seizure freedom with surgical treatment.4,11,12 The best outcomes are subject to confirmation of a single epileptogenic focus.5 Further research is needed to establish whether patients with suspected burned-out hippocampus syndrome should be treated surgically without prior invasive neurophysiological evaluation. The use of FOE may be a safe, effective alternative in presurgical decision-making.

FundingThe authors have received no funding for this study.

We are especially grateful to Dr Daniel Sanjuan Orta, epileptologist and clinical neurophysiologist, and head of the clinical research department at Instituto Nacional de Neurología y Neurocirugía, Mexico, and to Dr Nhora Patricia Ruiz Alfonzo, neurologist and epileptologist at Neurológicas Internacional, Piedecuesta, Colombia, for their kind and valued collaboration in the review and analysis of this article.

This study was performed within the Epilepsy Surgery Programme at the Neurological Institute of Hospital Internacional de Colombia, Piedecuesta, Santander, Colombia.

Please cite this article as: Freire Carlier ID, Andrade Rondón, SA, Silva Sieger FA, Freire Figueroa IA, Barroso Da Silva EA. Síndrome de hipocampo quemado, mito o realidad. Reporte de caso. Neurología. 2021;36:558–561.