Our purpose is to describe the demographic, clinical and therapeutic characteristics of patients with blepharospasm (BS) and hemifacial spasm (HFS) during treatment with botulinum toxin type A (BtA).

Patients and methodsRetrospective analysis of patients diagnosed with BS or HFS and treated with BtA in the Neurology Department at Complejo Asistencial de Segovia between March 1991 and December 2009 was carried out.

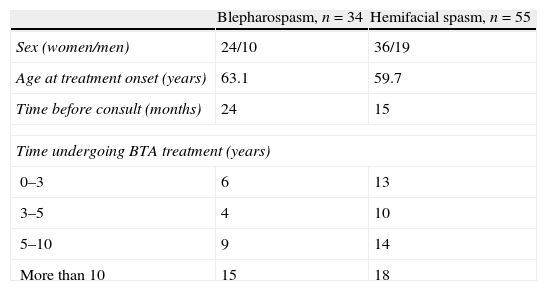

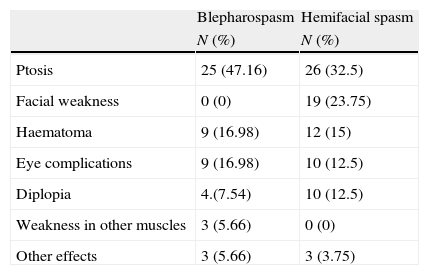

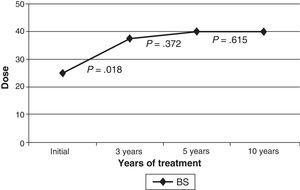

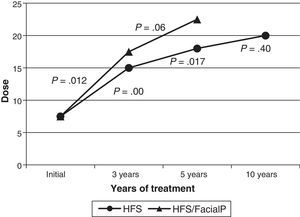

ResultsDifferent variables were collected from 34 patients with BS and 55 with HFS, of whom 44.1% and 32.7% respectively had been undergoing treatment with BtA for more than 10 years. Elapsed time from symptom onset to the first visit was 24 months in the BS group and 59.7 months in the HFS group. Diagnosis was given during the first visit for 76.5% of the BS patients and 90.7% of the HFS patients. Patients were referred by their primary care centres in 34.6% of the cases with BS and in 77.6% of the cases with HFS. The most commonly used BtA preparation was BOTOX® in both groups, and there were no cases of primary or secondary resistance. The median dose of BtA was raised gradually in both groups, and the increase was statistically significant during the early years of treatment. The most common side effect was ptosis (47.1% in BS, 32.5% in HFS).

ConclusionsBS and HFS are the most common facial movement disorders. The demographic and clinical characteristics and therapeutic findings from this study show that treatment with BtA is both effective and safe over the long term.

Nuestro objetivo es describir las características clinicoepidemiológicas y terapéuticas de los pacientes con blefarospasmo (BS) y espasmo hemifacial (EH) en tratamiento con toxina botulínica tipo A (TBA).

Pacientes y métodosSe estudió retrospectivamente a los pacientes diagnosticados de BS y EH en tratamiento con TBA en la consulta de neurología del Complejo Asistencial de Segovia, desde marzo del 1991 hasta diciembre del 2009.

ResultadosSe recogieron distintas variables de 34 pacientes con BS y 55 pacientes con EH, de los cuales el 44,1 y el 32,7%, respectivamente, llevaban más de 10 años en tratamiento con TBA. Desde el inicio de los síntomas hasta la consulta la mediana de tiempo fue de 24 meses en el grupo de BS, y de 59,7 meses en el grupo de EH, diagnosticándose en la primera visita el 76,5 y el 90,7%, respectivamente. El 34,6% de los pacientes con BS y el 77,6% de los pacientes con EH fueron derivados desde atención primaria. En ambos grupos, el preparado farmacológico de TBA más utilizado fue BOTOX®, sin hallarse resistencias primarias ni secundarias. La mediana de la dosis se incrementó progresivamente en ambas entidades, de forma significativa en los primeros años de tratamiento. La ptosis fue el efecto secundario más frecuente (el 47,1% en el BS, el 32,5% en el EH).

ConclusionesEl BS y el ES constituyen los trastornos del movimiento faciales más comunes, recogiendo en esta serie diferentes parámetros epidemiológicos, clínicos y terapéuticos, confirmándose el beneficio y la seguridad del tratamiento con TBA a largo plazo.

Dystonia is defined as a sustained involuntary muscle contraction that causes abnormal postures or repetitive twisting movements. Depending on its location, it can be classified as generalised, segmental, hemidystonia, multifocal, or focal. Focal dystonias include blepharospasm (BS), which is characterised by spasmodic contractions of the orbicularis oculi and adjacent muscles. If BS is accompanied by contractions in other facial muscles, the condition is called Meige syndrome. Hemifacial spasm (HFS) is not considered to be a form of dystonia, but rather a peripheral movement disorder. It is generally idiopathic and characterised by irregular involuntary tonic and/or clonic contractions of muscles innervated by the facial nerve.1,2 Treatment options for BS and HFS alike include drugs, surgical procedures, and infiltration with botulinum toxin (BT).3,4

Botulinum toxin is applied to the affected muscles by means of subcutaneous injection. The toxin acts by inhibiting the release of acetylcholine in the neuromuscular junction, which gives rise to temporary denervation. Two BT serotypes are commercially available: type A (BTA) and type B. Their potency is expressed in units. Side effects of using BT for either BS or HFS are similar, and include ptosis, pain at the injection site, facial paresis, diplopia, ecchymosis, keratitis due to corneal exposure, ectropion, and entropion.3–5 Types of treatment failure may be primary (meaning that it occurs with the initial dose of BTA and may correspond to biological resistance to the toxin) or secondary (meaning that it appears after earlier treatments were effective). Secondary treatment failure may be caused by exacerbation of the initial symptoms, technical problems, or the development of antibodies able to neutralise the toxin.3,4,6–9

This study describes results from an analysis of clinical, epidemiological, and treatment characteristics of a large sample of patients with BS and HFS who underwent long-term treatment with BTA.

Patients and methodsRetrospective analysis of epidemiological, clinical, and progression characteristics of patients diagnosed with BS and HFS and undergoing treatment with BTA injection at the neurology department at Complejo Asistencial de Segovia between March 1991 and December 2009 was carried out. BTA injections contained a preparation of BTA solution mixed with 2cm3 of 0.9% sterile saline solution for Botox® (5U in 0.1cm3) and 2.5cm3 of 0.9% saline for Dysport® (20U in 0.1cm3). The Botox®:Dysport® dose–equivalence ratio was 1:4. Injections were administered subcutaneously. Muscles infiltrated with BTA, according to each patient's needs, included the preseptal/pretarsal orbicularis oculi, peribuccal muscles, and platysma. Patients with Meige syndrome may also have received injections in other cranio-cervical muscles. Dose was calculated according to spasm severity and location, and with reference to guidelines in the literature. Apart from the BTA injections scheduled at least every 12 weeks, patients received no reinforcement doses. We also recorded causes of treatment drop-out, indicating cases of patients who died or were lost to follow-up, etc.

Data were analysed by using the SPSS statistical package v. 15.0 for Windows. We completed a descriptive analysis of patients’ demographic, clinical, and treatment data. Dosage changes were evaluated using the Wilcoxon test for paired samples. Between-group comparison of quantitative variables was performed using the chi-square test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for group comparison. The significance level was P<.05.

ResultsBlepharospasmThe study included 34 patients with BS, predominantly women; the period prevalence was 2.2 per 100000 patients per year. Additional patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

The departments that most frequently referred these patients were primary care (34.6%) and ophthalmology (30.8%). The most common suspected diagnoses included requests for a neurological consult were BS (42.9%), tic (25%), ptosis (14.3%), myasthenia (7.3%), and diplopia (3.6%).

MRI, employed in 30.8% of the cases, was the most commonly performed diagnostic test; there were no cases of structural changes. Meige syndrome was diagnosed at onset in 9 patients (26.5%) based on the presence of oromandibular dystonia. Four more patients (11.8%) also developed the disease at some point during follow-up (a median of 36 months later).

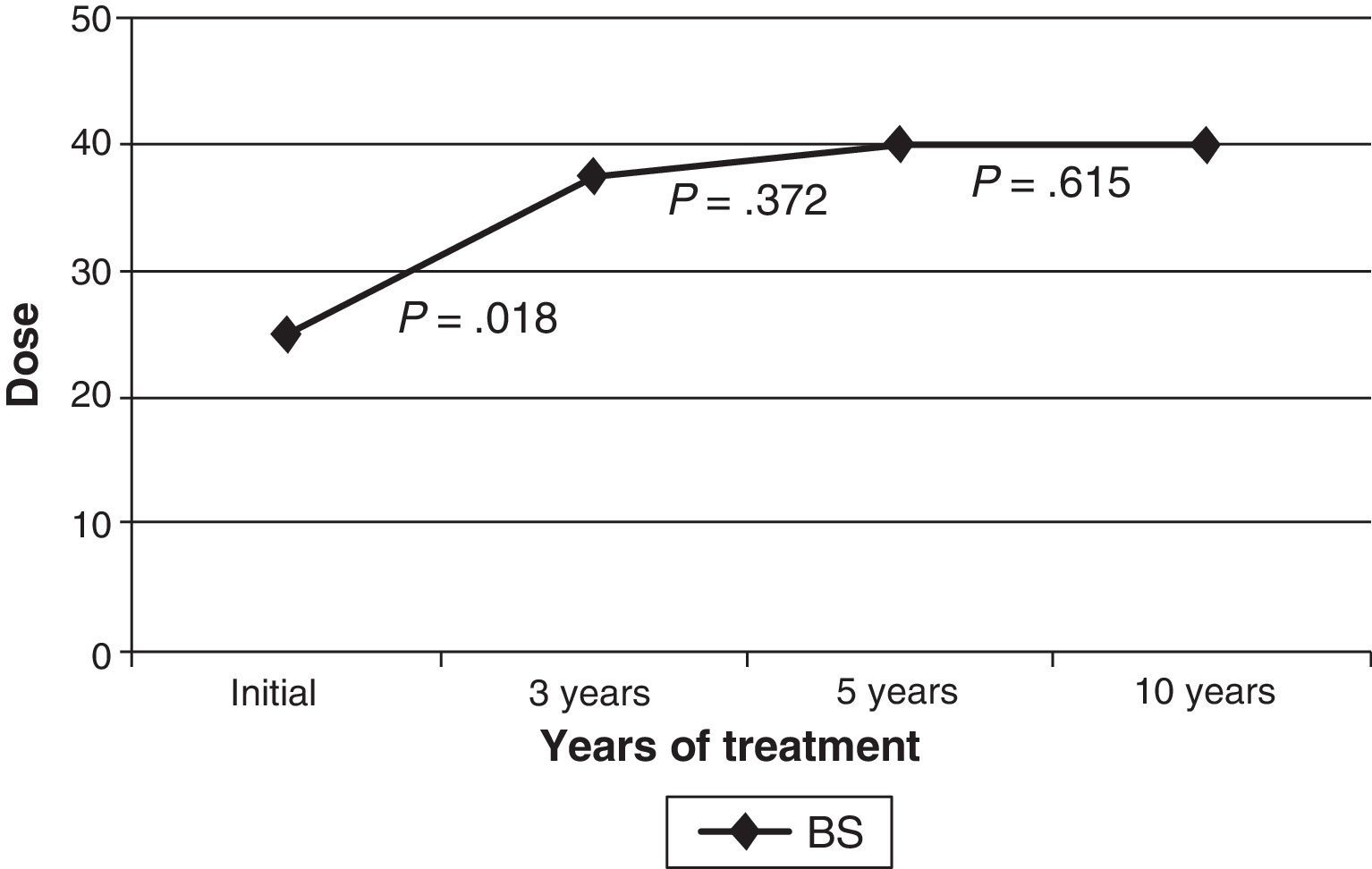

The initial drug preparation in all cases was Botox®; 2 patients (5.9%) changed to Dysport® because of suspected secondary resistance (not confirmed by a resistance test). Patients’ benefits from both preparations were similar. In the beginning, injections targeting the orbicularis were delivered to preseptal locations. A pretarsal injection was administered after 3 years to 27 patients (79.4%); after 5 years to 23 patients (67.6%); and after 10 years to 14 patients (41.2%). The injection location was changed from the preseptal to the pretarsal area of the orbicularis oculi in order to make the treatment more effective, and in some cases, to avoid ptosis as a side effect as well. The median dose (the sum of doses in both orbicularis oculi) was 25U upon starting treatment, 37.5U at 3 years, and 40U at 5 and 10 years. The mean dose increased progressively with time, but this difference was only statistically significant between treatment onset and the 3-year mark (Fig. 1). Patients who required additional treatment for muscles other than the orbicularis oculi (cranial or cervical muscles) began that treatment a median time of 24 months after the initial dose.

There were no cases of primary or secondary resistance. Side effects appeared in 29 patients (85.3%) at some point during follow-up, with no cases of systemic adverse effects (Table 2). Within a period of 1 to 4 years after starting treatment, 4 patients (11.7%) were discharged from follow-up due to improvement of symptoms. Four patients were lost to follow-up for unknown reasons (in-depth examination of their medical histories could provide no evidence as to why they stopped coming to their appointments). None of the patients left treatment due to side effects.

Side effects of BTA treatment in patients with BS or HFS.

| Blepharospasm | Hemifacial spasm | |

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Ptosis | 25 (47.16) | 26 (32.5) |

| Facial weakness | 0 (0) | 19 (23.75) |

| Haematoma | 9 (16.98) | 12 (15) |

| Eye complications | 9 (16.98) | 10 (12.5) |

| Diplopia | 4.(7.54) | 10 (12.5) |

| Weakness in other muscles | 3 (5.66) | 0 (0) |

| Other effects | 3 (5.66) | 3 (3.75) |

The study recruited 55 patients with HFS, predominantly women; the period prevalence was 3.7 per 100000 patients/year. Additional patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Of the patient total, 90.7% were diagnosed during their first visit. Most of the patients were referred by primary care (77.6%), followed by ophthalmology (8.2%). Suspected diagnoses given in requests for consults were, in order of frequency: tic (38.8%), HFS (18.4%), facial paralysis (12.2%), ptosis (10.2%), BS (6.1%), diplopia (2%), myasthenia (2%), and tinnitus (2%).

Eighteen of the 55 patients with HFS (32.7%) had a history of facial paralysis (post facial paralysis synkinesis). HFS was right-sided in 34 patients (61.8%) and left-sided in 21 (38.2%). MRI was the most commonly-used diagnostic test (employed in 60.9% of cases). Vascular compression of the nerve at the base of the cranium was observed in 4 cases, and low grade brainstem glioma in a single case.

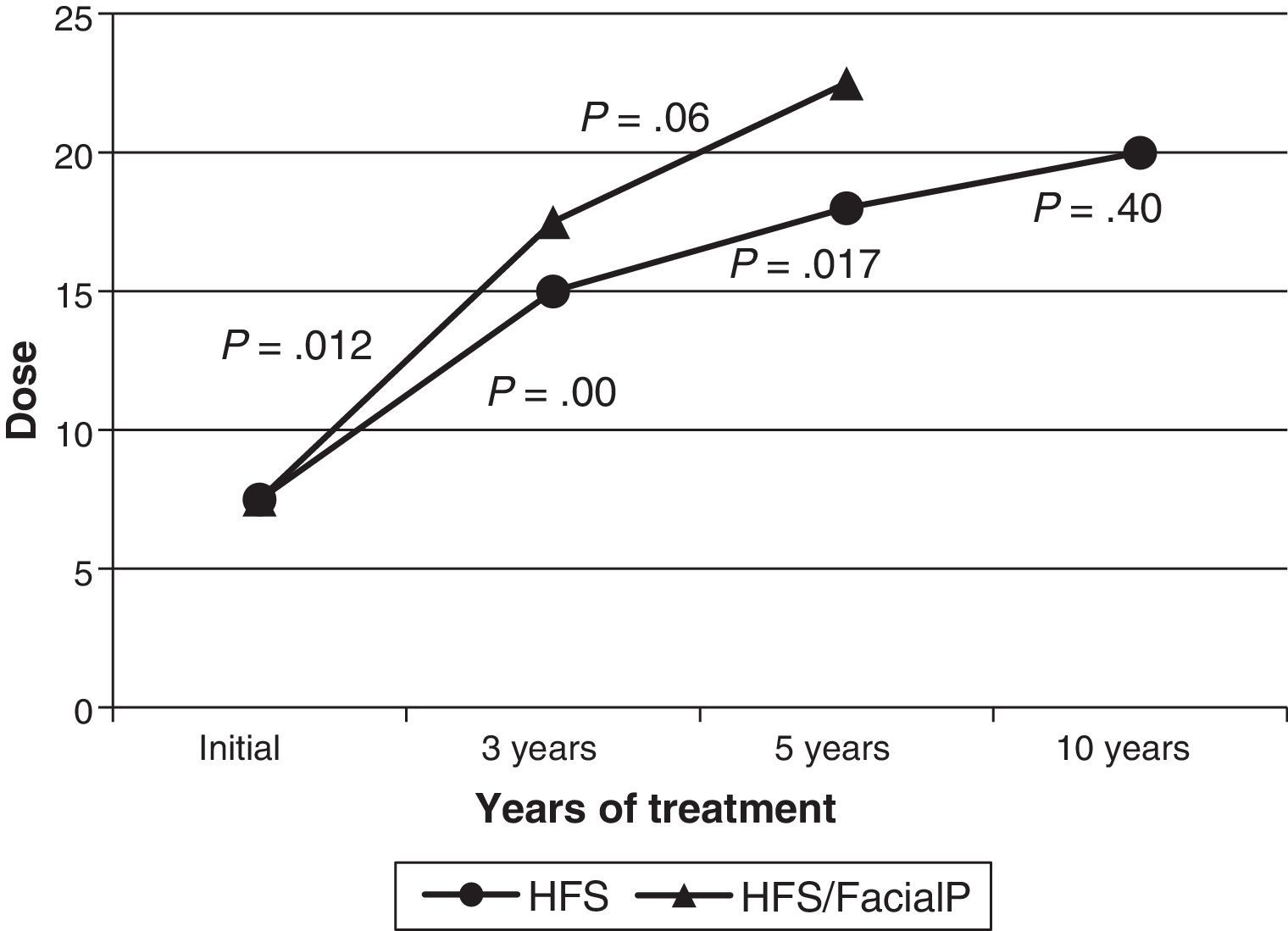

Botox® was used as the initial treatment in all patients. In 2 cases (3.6%), treatment was changed to Dysport® due to suspected local cutaneous allergic reaction in one case and low effectiveness in the other. The latter case did not obtain better results with the new formula. The median dose delivered to the orbicularis oculi at treatment onset was 7.5U; by 3 years, it had been increased to 15U; by 5 years, 18U; and by the 10-year mark, it had reached 20U. The increase detected in the median dose over time was statistically significant between onset and the 3-year mark, and between the 3-year and 5-year marks. The dosage increase was not significant between the 5-year and 10-year marks. The median dose at onset among patients with a history of facial paralysis (18 cases) was 7.5U; at 3 years, 17.5U (12 cases); and at 5 years, 22.5U (7 cases). Only one patient with a history of facial paralysis had been in treatment for more than 10 years. As in patients without a history of facial paralysis, the median dose increased progressively. This difference was only statistically significant between onset and the 3-year mark (Fig. 2). Comparison between the median doses for the subgroup of patients with a history of facial paralysis and the subgroup with no such history reveals no significant differences in any of the periods we compared (onset, 3 years, and 5 years). Thirty-one patients (56%) required injections in muscles other than the orbicularis oculi. Specifically, 22 patients (40%) needed BTA in the zygomaticus, 6 patients (11%) in the zygomaticus and platysma, and 3 patients (5%) in the platysma. Treatment at the locations listed above began a median of 12 months after starting BTA, and patients did not consistently receive injections at those locations.

There were no cases of primary or secondary resistance. At least one side effect during follow-up was recorded in 42 patients (76.4%). There were no systemic adverse effects (Table 2). Of the total, 9% (5 patients) were discharged from follow-up due to having improved to the point of not needing any further BTA injections within a period of 3 to 10 years after treatment onset. Patients were lost to follow-up for the following reasons: side effects (2 patients), death (1 patient), severe concomitant illnesses (2 patients), and unknown (1 patient). There were no significant relationships between appearance of side effects and leaving treatment (P=.423).

DiscussionA total of 89 patients were studied (34 with BS and 55 with HFS) to evaluate different epidemiological, clinical, and treatment parameters. We will now present the most important results.

Epidemiological findings were similar to those in earlier studies with regard to sex (female predominance) and age at onset.1,2

MRI was the test most commonly used to rule out secondary causes. However, despite recommendations that this study should be completed in all cases, it was only performed on 50.9% of the patients with HFS. These data may be explained in part because some of the patients we included were diagnosed years ago, when MR imaging was not available in most hospitals.

Important studies addressing long-term treatment with BTA include the series by Snir et al.,10 which included 27 patients (17 with BS and 10 with HFS) over 4-year and 6-year treatment periods, and the series by Cillino et al.,11 which included 73 patients with BS and 58 with HFS over a 10-year period. Mejía et al.12 evaluated effectiveness, safety, and immune response to BTA with a mean of 12 years of follow-up on different dystonia types. However, the study only included 4 patients with BS, 6 with craniocervical dystonia, and 1 with HFS. Other noteworthy studies include those by Pérez-Saldaña et al.,13 Jitpimolmard et al.,14 Defazio et al.,15 and Barbosa et al.,16 all of which included HFS patients. We also find the series by Echeverría Urabayen et al.,17 which included patients with BS and evaluated changes in BTA dosage as a sole parameter, and the study by Mauriello et al.18 of patients with BS and Meige syndrome. All of these studies concluded that long-term treatment of BS and HFS using either BTA preparation is effective and safe. Gill et al.19 analysed response to BTA in 18 patients with BS and 16 patients with HFS and concluded after more than 30 doses that the treatment was beneficial and safe. They observed that in patients with BS, time to symptom relief was shorter for more recent doses than for initial ones, and that the difference was significant; this difference in time to relief was not detected in HFS patients.

Regarding changes in dose over time, results vary from study to study. Echeverría Urabayen et al.17 reported a small but significant decrease in BTA dose over a non-linear period in patients with BS. In the series by Defazio et al.,15 the BTA dose remained constant over time in HFS patients. Gill et al.19 observed a non-significant dosage increase in HFS cases. In other series, doses increased after treatment onset in both BS and HFS cases.10–13,16,20 In our study, doses of BTA increased progressively, and the increase was significant in the first years of treatment. This could be explained by the fact that low doses are initially used in accordance with guidelines in the literature, and that they are later modified according to the clinical severity and location of the muscle spasm. It may also be explained by a patient's developing resistance to BTA secondary to antibody formation, but this would be unlikely. Although antibodies were not measured by laboratory testing, results from all patients tested clinically for resistance were negative. Development of partial resistance could provide an explanation. Other reasons may include a learning effect or the possibility of an initial placebo effect.

Comparison between the median doses for the subgroup of patients with a history of facial paralysis and the subgroup with no such history revealed no significant differences for any of the 3 study periods. Kollewe et al.21 found no differences in response to treatment with either of the BTA preparations among patients with HFS and post facial palsy synkinesis, whether of traumatic or idiopathic origin. Nevertheless, Pérez-Saldaña et al.13 described patients with post facial palsy synkinesis as needing lower doses. This may be related to the presence of residual facial palsy, or it may indicate an underlying process that is more benign and has a stable course.

As in prior studies,5,11,13–15,21–23 the most common side effect was ptosis. A few series listed dry eyes as the most common side effect, with ptosis ranked second.10,18,24 All side effects caused by treatment were reversible and could be controlled by adjusting the BTA dose.

Several infiltration techniques intended to optimise response to BTA have been assessed in terms of best response, longest effect duration, and fewest side effects. Cakmur et al.25 completed a retrospective study of 25 patients with BS and 28 patients with HFS that compared pretarsal injections with preseptal injections. They found higher response rates and longer effect duration in the group receiving pretarsal injections. The most common side effect in both groups was ptosis, which was less common in the pretarsal injection group than in the preseptal injection group. Other studies support these findings; Aramideh et al.26 concluded that additional BTA injections increase benefits of treatment and decrease the number of cases of treatment failure and ptosis. They did discover, however, a significant increase in blurry vision upon adding pretarsal injections. In this series, the BS group received pretarsal injections, unlike patients in the HFS group. The data do not indicate whether this was beneficial, or if delivering these injections modified the frequency of side effects.

Even among medical professionals, BS and HFS are little-known entities, as demonstrated by the suspected diagnoses that led doctors to request consults. The obscurity of these conditions means that they are probably underdiagnosed, and that some patients may not be receiving proper treatment.

Although this study offers a retrospective view of follow-up on patients undergoing continuous BTA treatment, it is a descriptive study, meaning that data should be interpreted cautiously. Since we reviewed medical histories spanning many years of progression, some data could not be included simply because they had never been recorded. Examples include time elapsed between the injection and the treatment response, duration of maximum response, and patients’ assessments. Although our data does not include results from quality assessments, we believe that the effect of BTA remains beneficial and safe after years of treatment administration based on the fact that patients asked to continue treatment because they felt it was helping.

In conclusion, BS and HFS are progressive movement disorders that affect patients’ quality of life. BTA is the best treatment option for both conditions based on its being effective and safe for long-term treatment.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gil Polo C, et al. Blefarospasmo y espasmo hemifacial: tratamiento a largo plazo con toxina botulínica. Neurología. 2013;28:131–6.

Partial results from this study were presented in poster format at the 62nd Annual Meeting of the SEN.