Around 50% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) experience central nervous system alterations at some stage of the disease.1 Common manifestations of neurological lupus include headache, seizures, visual alterations, stroke, myelitis, movement disorders, memory impairment, personality changes, and depression.2

We describe the case of a 33-year-old man who presented a haemorrhagic variant of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), which led to a diagnosis of LES.

The patient arrived at the hospital with nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and fever. His medical history included an isolated psychotic episode 10 years previously and several consultations with his primary care doctor due to episodes of pleuritic pain and painful joint inflammation. He was being treated with risperidone, biperiden, and citalopram.

On the fourth day of hospitalisation, he presented weakness in the lower limbs and sphincter dysfunction. Physical examination revealed flaccid areflexic paraparesis and hypoaesthesia. Brain and spinal CT scans showed no relevant findings. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed lymphocytic pleocytosis with 90cells/μL (96% mononuclear cells), elevated protein levels (328mg/dL), and normal glucose levels (57mg/dL). The patient started corticosteroid treatment: 10mg dexamethasone followed by 4mg every 6hours. Ten hours later, he presented dysarthria, diplopia, and progressive dyspnoea. A neurological examination revealed bilateral horizontal ophthalmoplegia, bilateral facial paralysis, and upper limb weakness. Oxygen saturation was 88% at an oxygen flow rate of 15L/min. The patient was intubated orotracheally to maintain adequate ventilation, and transferred to the intensive care unit.

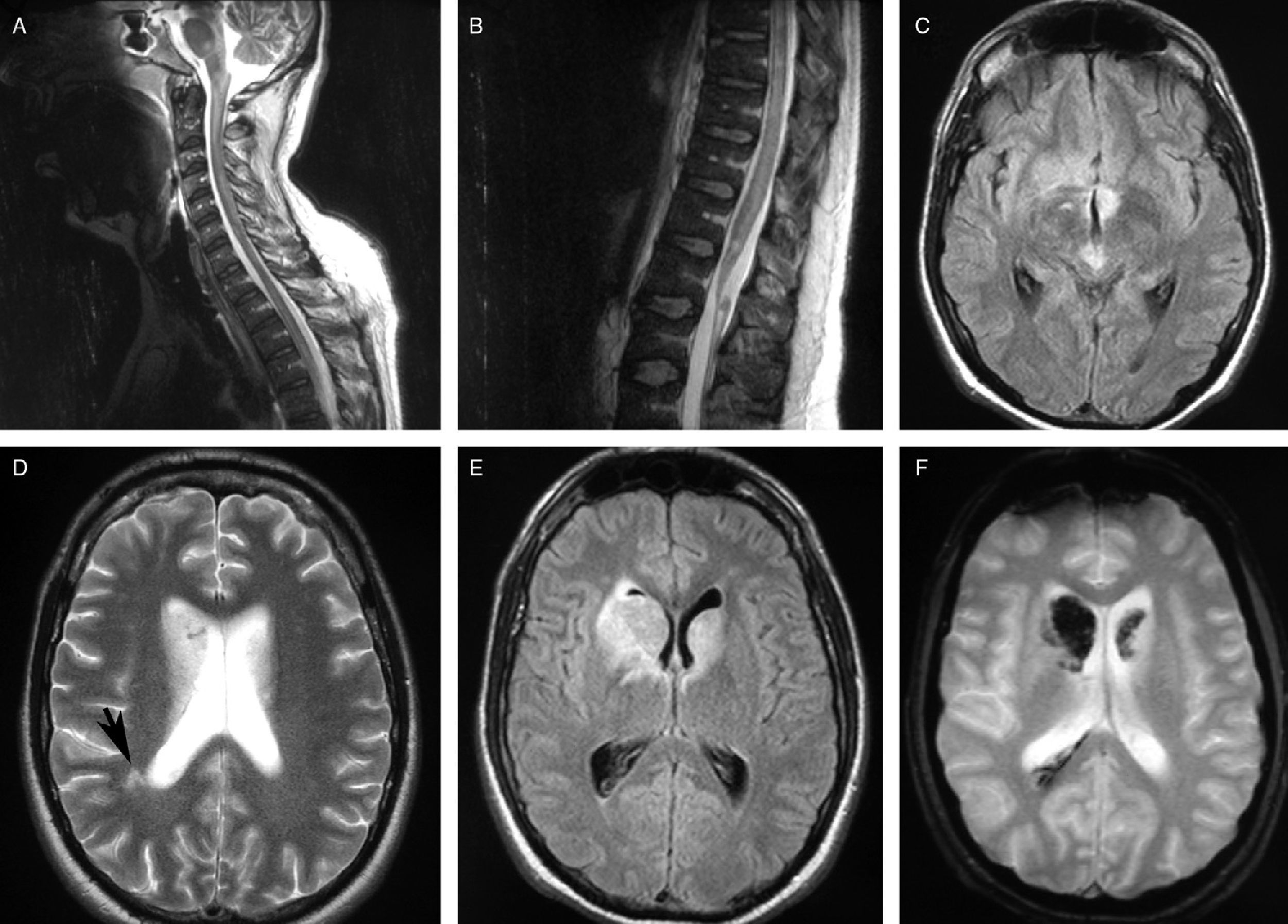

The brain and spinal MRI scan showed an extensive hyperintense lesion on FLAIR; the T2 sequence showed a lesion extending from the brain to the medullary cone mainly affecting the brainstem and the subcortical region. Hypointense T2-weighted gradient echo MRI signals in both caudate nuclei suggested haemorrhage (Fig. 1).

MR images. (A) and (B) Sagittal T2-weighted sequences displaying hyperintense lesions in the spinal cord and brainstem. (C) Axial FLAIR sequence showing hyperintense lesions in the mesencephalic tegmentum and the hypothalamic region. (D) Axial T2-weighted sequence showing increased signal in both caudate nuclei and subcortical white matter. (E) Axial FLAIR T2-weighted sequence exhibiting lesions in both caudate nuclei. (F) Axial T2-weighted gradient echo sequence showing a hypointense signal in the caudate nucleus, which suggests a haemorrhagic component.

The blood analysis revealed microcytic anaemia, leukocytopenia, lymphocytopenia, 249000platelets/μL, antinuclear antibodies (ANA) with a titre of 1:320, anti-double stranded DNA antibodies (33kU/L), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), and hypocomplementemia (70mg/dL); results from the Coombs test were positive. Other tests (biochemical, renal function, hepatic enzymes, coagulation, electrocardiogram, chest radiography, microbiological, and serological) yielded normal results, including negative results for antiphospholipid antibodies and aquaporin 4 (AQP4).

The patient began immunosuppressive treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone (1g/day for 3 days), intravenous immunoglobulin (0.4g/kg/day for 5 days), plasmapheresis (6 sessions), and intravenous cyclophosphamide. He improved slightly and was transferred to the neurology ward to start rehabilitation treatment. While he was hospitalised, he developed femoral deep vein thrombosis (DVT), so we initiated anticoagulant treatment with acenocoumarol. He was then transferred to a rehabilitation centre; he presented severe paraparesis and bilateral facial paralysis at discharge.

He was diagnosed with a haemorrhagic variant of ADEM associated with SLE. The diagnosis of SLE followed the classification criteria of the American College of Rheumatology.3 Our patient met 6 of them: arthritis, pleuritis, neurological disorders, haematological disorders, positive ANA, and immunologic disorder (anti-DNA+).

Our patient's neurological manifestations were compatible with ADEM, a monophasic inflammatory illness of the central nervous system that occurs in post-infection settings.4 The diagnostic criteria for ADEM are not well defined. MR images in patients with ADEM show extensive confluent symmetric lesions in the white matter and basal ganglia. The CSF usually displays a non-specific increase in cell count.5 Our patient initially exhibited acute longitudinal myelitis a few days after having a gastrointestinal infection. In addition to the symptoms of myelitis, the patient presented symptoms secondary to brainstem lesions. CSF test results and MRI findings which indicated lesions simultaneously affecting several structures of the brain and spinal cord were compatible with ADEM.

Although acute transverse myelitis is not frequently found in patients with SLE, the literature includes several case reports and case series describing patients with both entities.6 Very few cases of the copresence of brain lesions and myelitis have been reported. Bermejo et al.7 described a case of haemorrhagic encephalomyelitis as a form of SLE which manifested clinically as transverse myelitis. Brain lesions were asymptomatic; radiological findings included haemosiderin deposits in the corpus callosum, spinal cord, and several white matter regions. Another case of ADEM and SLE8 was diagnosed based on brain and spinal cord MR images, which showed extensive diffuse involvement of the subcortical white matter, basal ganglia, corpus callosum, and cerebellar peduncles. That case was positive for lupus anticoagulant; this finding, which has been reported in a subgroup of patients with SLE and myelitis,9 was not identified in our case. Our patient developed DVT despite prophylactic treatment with heparin, probably because he had remained immobilised for a lengthy period.

The differential diagnosis included neuromyelitis optica since this entity often coexists with other autoimmune diseases. However, this diagnosis was unlikely since blood analysis results were negative for AQP4 and no improvements were seen after plasmapheresis and corticosteroid treatment.10,11

Although demyelinating diseases are included among the 19 neurological and psychiatric manifestations of SLE proposed in the consensus document published by the American College of Rheumatology in 1999,12 histological findings of demyelinating lesions have rarely been reported. Shintaku and Matsumoto13 described a patient with neurological lupus who displayed disseminated perivenous demyelinating necrotic lesions at autopsy. The most common histopathological findings in patients with neurological lupus are macro- and microthrombi, focal lesions indicating infarct, and vascular remodelling.14

A number of factors are thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of neurological lupus, including antibody production, acute inflammation associated with intrathecal production of proinflammatory cytokines, and thrombotic lesions secondary to a hypercoagulable state due to the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies.15 The integrity of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) may be an influential factor in the pathogenesis of neurological lupus.16 The processes leading to penetration of the BBB, such as infections, may act as triggering factors allowing proteins or cells to access the central nervous system. In our case, the gastrointestinal infection may have triggered the process.

In conclusion, we present an example proving that a haemorrhagic variant of ADEM may, although infrequently, present as a severe manifestation of SLE.

Please cite this article as: Gil Alzueta MC, Erro Aguirre ME, Herrera Isasi MC, Cabada Giadás MT. Encefalomielitis aguda diseminada como complicación del lupus eritematoso sistémico. Neurología. 2016;31:209–211.

Presented at the 61st Annual Meeting of the SEN.