Advances in the treatment of myasthenia gravis (MG) have improved quality of life and prognosis for the majority of patients. However, 10%–20% of patients present refractory MG, with frequent relapses and significant functional limitations.

Patients and methodsPatients with refractory MG were selected from a cohort of patients diagnosed with MG between January 2008 and June 2019. Refractory MG was defined as lack of response to treatment with prednisone and at least 2 immunosuppressants, inability to withdraw treatment without relapse in the last 12 months, or intolerance to treatment with severe adverse reactions.

ResultsWe identified 84 patients with MG, 11 of whom (13%) met criteria for refractory MG. Mean (standard deviation) age was 47 (18) years; 64% of patients with refractory MG had early-onset generalised myasthenia (as compared to 22% in the group of patients with MG; P < .01), with a higher proportion of women in this group (P < .01). Disease severity at diagnosis and at the time of data analysis was higher among patients with refractory MG, who presented more relapses during follow-up. Logistic regression analysis revealed an independent association between refractory MG and the number of severe relapses.

ConclusionsThe percentage of patients with refractory MG in our series (13%) is similar to those reported in previous studies; these patients were often women and presented early onset, severe forms of onset, and repeated relapses requiring hospital admission during follow-up.

Los avances en el tratamiento de la miastenia gravis (MG) han conseguido mejoría en la calidad de vida y el pronóstico de la mayoría de los pacientes. Sin embargo, un 10-20% presenta la denominada MG refractaria sin alcanzar mejoría, con frecuentes recaídas e importante repercusión funcional.

Pacientes y métodosSe seleccionó a pacientes con MG refractaria a partir de una cohorte de pacientes con MG diagnosticados desde enero del 2008 hasta junio del 2019. Se definió MG refractaria como falta de respuesta al tratamiento con prednisona y al menos 2 inmunosupresores o imposibilidad para la retirada del tratamiento sin recaídas en los últimos 12 meses o intolerancia al mismo con graves efectos secundarios.

ResultadosSe registraron 84 pacientes con MG, 11 cumplían los criterios de MG refractaria (13%), con una edad media de 47 ± 18 años; un 64% los pacientes con MG refractaria fueron clasificados como miastenia generalizada de comienzo precoz (p < 0,01) con una mayor proporción de mujeres (p < 0,01). La gravedad de la enfermedad al diagnóstico, así como en el momento del análisis de los datos, fue superior en el grupo de MG refractaria con un mayor número de recaídas en el seguimiento. En el modelo de regresión logística se obtuvo una asociación independiente entre MG-R y el número de reagudizaciones graves.

ConclusionesEl porcentaje de pacientes con MG refractaria en nuestra serie (13%) es similar al descrito en estudios previos, con frecuencia mujeres con inicio precoz, formas graves de inicio y reiteradas reagudizaciones con ingreso hospitalario en el seguimiento.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease mediated by antibodies targeting proteins located on the postsynaptic membrane of the motor endplate. These antibodies inhibit the normal functioning of the acetylcholine receptor, blocking neuromuscular transmission and causing skeletal muscle weakness.1 Though MG is a rare disease, with fewer than 2 cases per 10 000 population in Europe, an upward trend has been observed in the number of diagnoses in recent years, mainly due to increased incidence in older age groups (> 50 years).2

The term gravis refers to the fact that the natural course of the disease was associated with high rates of mortality and particularly morbidity, with a substantial impact on activities of daily living and quality of life.3 Today, outcomes have improved due to the treatments available, including corticosteroids and conventional immunosuppressants (azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, etc.); thymectomy in selected cases; and intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) or plasma exchange (PLEX) in the event of clinical worsening.4 Thanks to these treatments, the majority of patients remain pauci- or asymptomatic with or without pharmacological treatment.

However, some patients do not adequately respond to standard treatment, developing what is known as refractory MG, and continue to present symptoms, frequent exacerbations, and adverse reactions to corticotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy.5 The exact prevalence of refractory MG is unknown, but it is estimated to account for 10%–20% of cases of MG.5,6 Generally, these patients are reported to present higher rates of myasthenic crises, hospital admissions, and emergency care than patients with non-refractory MG, with a considerable impact on their quality of life. Despite this, few studies have addressed this highly relevant subgroup of patients with MG.7

This study aims to describe the clinical characteristics of patients with refractory MG in a hospital cohort of patients with the disease.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective, observational prevalence and cross-association study of a series of consecutive patients with MG attended at the neuromuscular disease clinic of Hospital Universitario de Albacete between January 2008 and June 2019. MG was diagnosed according to the presence of clinical symptoms of skeletal muscle weakness and fatigability associated with the detection of anti–acetylcholine receptor (anti-AChR) or anti–muscle-specific kinase (anti-MuSK) antibodies in the serum. Diagnosis of seronegative forms was based on findings confirming altered postsynaptic neuromuscular transmission in a neurophysiological study including repetitive low-frequency stimulation or single-fibre electromyography. Among the total cohort, we selected those with refractory MG, defined according to the international consensus guidance for the management of MG8: persistence of disabling symptoms despite treatment with prednisone and at least 2 immunosuppressants in the last year, at appropriate doses and treatment duration; inability to withdraw treatment without exacerbations in the last 12 months; or intolerance to pharmacological treatment with severe adverse reactions in the last 12 months. The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) classification was used to rate disease severity at diagnosis and at the time of data analysis. In addition to the typical demographic variables, such as age and sex, we analysed the proportion of patients with early onset (symptom onset before 50 years of age), presence of thymoma, treatments prescribed, and the number of exacerbations requiring rescue therapy with IVIg or PLEX.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee and complied with good clinical practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. Data were stored confidentially and used exclusively for research purposes.

Statistical analysisWe conducted a descriptive analysis of the data obtained, with categorical variables expressed as frequencies and percentages and quantitative variables as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median and quartiles 1 and 3 (Q1–Q3), depending on whether data followed a normal distribution. We divided the sample into 2 subgroups, refractory and non-refractory MG, and conducted a bivariate comparative analysis of the relevant demographic and clinical variables, using the chi-square test for qualitative variables and the t test and Mann–Whitney U test for normally and non–normally distributed quantitative variables, respectively. Finally, we performed a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis, with the model including all those variables displaying a statistically significant association in the bivariate analysis, in order to prevent the influence of potential confounders.

ResultsBetween January 2008 and June 2019, our clinic attended a total of 84 patients diagnosed with MG; the sample presented a mean age (SD) at diagnosis of 59 years (17), with a slight predominance of men (female/male ratio of 0.8). Mean follow-up time was 86.5 (50.8) months (range, 36–201).

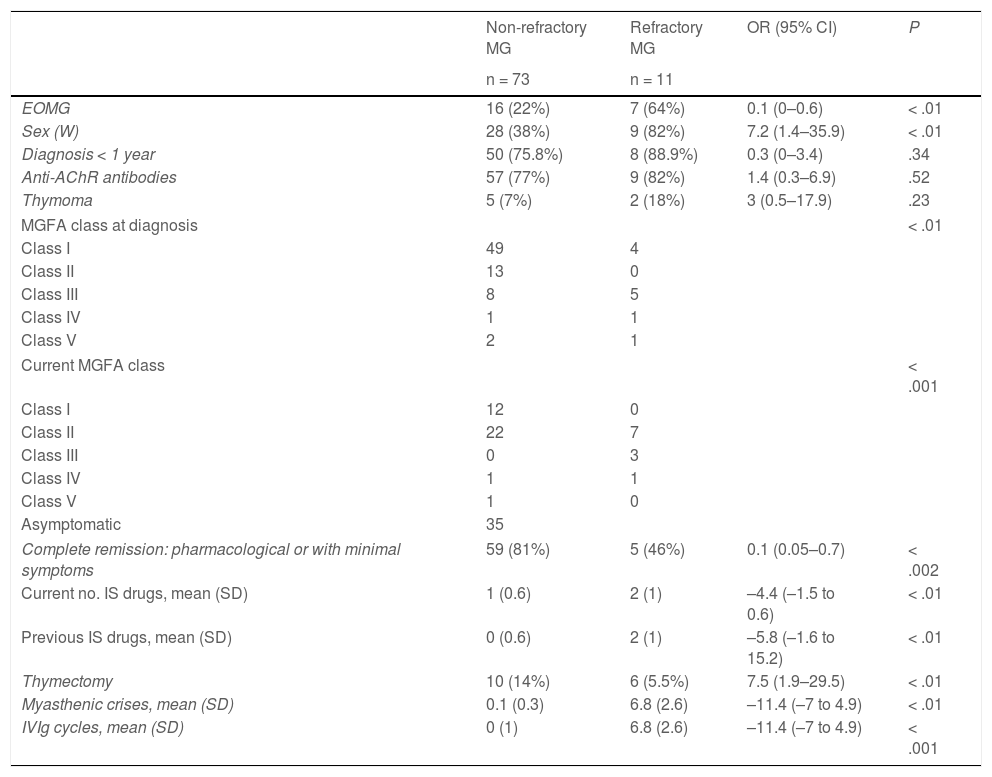

Of the total cohort, 11 patients (13%) met diagnostic criteria for refractory MG. Table 1 shows the main demographic and clinical data from the refractory and non-refractory MG subgroups.

Clinical characteristics of patients with refractory and non-refractory myasthenia gravis.

| Non-refractory MG | Refractory MG | OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 73 | n = 11 | |||

| EOMG | 16 (22%) | 7 (64%) | 0.1 (0–0.6) | < .01 |

| Sex (W) | 28 (38%) | 9 (82%) | 7.2 (1.4–35.9) | < .01 |

| Diagnosis < 1 year | 50 (75.8%) | 8 (88.9%) | 0.3 (0–3.4) | .34 |

| Anti-AChR antibodies | 57 (77%) | 9 (82%) | 1.4 (0.3–6.9) | .52 |

| Thymoma | 5 (7%) | 2 (18%) | 3 (0.5–17.9) | .23 |

| MGFA class at diagnosis | < .01 | |||

| Class I | 49 | 4 | ||

| Class II | 13 | 0 | ||

| Class III | 8 | 5 | ||

| Class IV | 1 | 1 | ||

| Class V | 2 | 1 | ||

| Current MGFA class | < .001 | |||

| Class I | 12 | 0 | ||

| Class II | 22 | 7 | ||

| Class III | 0 | 3 | ||

| Class IV | 1 | 1 | ||

| Class V | 1 | 0 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 35 | |||

| Complete remission: pharmacological or with minimal symptoms | 59 (81%) | 5 (46%) | 0.1 (0.05–0.7) | < .002 |

| Current no. IS drugs, mean (SD) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1) | –4.4 (–1.5 to 0.6) | < .01 |

| Previous IS drugs, mean (SD) | 0 (0.6) | 2 (1) | –5.8 (–1.6 to 15.2) | < .01 |

| Thymectomy | 10 (14%) | 6 (5.5%) | 7.5 (1.9–29.5) | < .01 |

| Myasthenic crises, mean (SD) | 0.1 (0.3) | 6.8 (2.6) | –11.4 (–7 to 4.9) | < .01 |

| IVIg cycles, mean (SD) | 0 (1) | 6.8 (2.6) | –11.4 (–7 to 4.9) | < .001 |

Anti-AChR: anti–acetylcholine receptor; EOMG: early-onset myasthenia gravis (< 60 years); IS: immunosuppressant; IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulins; MG; myasthenia gravis; MGFA: Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America classification; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation; W: woman; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

In the refractory MG subgroup, mean age at diagnosis was 47 (18) years, with 64% presenting early-onset MG (vs 22% in the non-refractory group; P < .01). The refractory MG group presented a higher percentage of women (82% vs 38%; P < .01). Seropositivity for anti-AChR antibodies (n = 9; 82%) and associated thymoma (n = 2; 18%) were also more frequent in the refractory MG group, although these differences were not statistically significant. No patient with refractory MG was seropositive for anti-MuSK antibodies.

The refractory MG group presented greater disease severity at diagnosis and at the time of data analysis: MGFA class ≥ 3 (moderate or severe MG) was recorded in 7 patients (64%) at diagnosis and in 4 at the end of the study period (36%) (Table 1).

All patients were receiving treatment with prednisone at various doses plus one immunosuppressant in 54% of patients (azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, ciclosporin, in one patient each, and rituximab in 3) and 2 immunosuppressants in the remaining patients (rituximab plus ciclosporin in 3 and rituximab plus mycophenolate mofetil in 2). Despite this treatment, no patient achieved complete symptom remission, with fewer than half (45%) achieving the treatment objective (minimal symptoms without functional impact), with an odds ratio of 5.2 (P < .02). Furthermore, 5 of the 11 patients with refractory MG presented one or more exacerbations requiring treatment with IVIg.

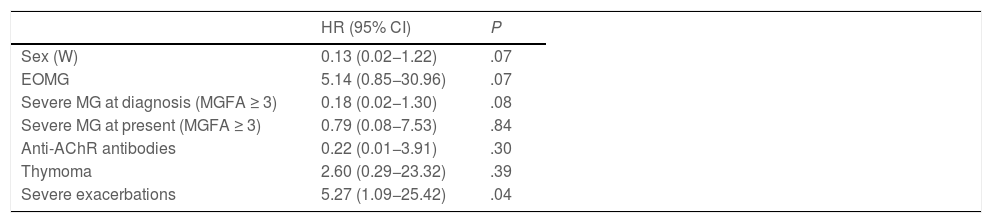

The bivariate analysis (Table 1) revealed that the refractory MG group presented a higher percentage of patients with early disease onset, a higher proportion of women, greater severity at diagnosis and at the time of data analysis, lower probability of achieving treatment objectives despite treatment with a greater number of immunosuppressant drugs, and a greater risk of exacerbations requiring rescue therapy with IVIg; all these differences were statistically significant. When we included these variables in the binary logistic regression model (Table 2), we only observed an independent association with the number of severe exacerbations during the follow-up period; female sex, severity at diagnosis, and early onset showed trends towards significance.

Binary logistic regression analysis of variables associated with refractory myasthenia gravis.

| HR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (W) | 0.13 (0.02−1.22) | .07 |

| EOMG | 5.14 (0.85−30.96) | .07 |

| Severe MG at diagnosis (MGFA ≥ 3) | 0.18 (0.02−1.30) | .08 |

| Severe MG at present (MGFA ≥ 3) | 0.79 (0.08−7.53) | .84 |

| Anti-AChR antibodies | 0.22 (0.01−3.91) | .30 |

| Thymoma | 2.60 (0.29−23.32) | .39 |

| Severe exacerbations | 5.27 (1.09−25.42) | .04 |

Anti-AChR: anti–acetylcholine receptor; EOMG: early-onset myasthenia gravis (< 60 years); HR: hazard ratio; MG: myasthenia gravis; MGFA: Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America classification; W: woman; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

This article presents a retrospective analysis of a series of patients with refractory MG from a larger cohort of patients with MG. Firstly, we observed a similar percentage of cases of refractory MG (13%) to that described in the literature, with previous studies establishing rates of 10%–20%.5–7 However, it is difficult to compare against other studies due to the lack of a consensus definition of refractory MG, although all definitions include the lack of response to conventional immunosuppressive therapy.9

Despite the small number of studies on refractory MG, the clinical profiles described in most previous studies coincide with our results.9,10 Thus, these patients are more frequently women, with early onset (< 50 years old) and severe generalised forms of MG at the time of diagnosis. Another noteworthy finding in our group of patients with refractory MG was that they required a continuous escalation of immunosuppressive therapy, frequently receiving such second-line drugs as rituximab, and presented greater likelihood of admission due to exacerbations requiring treatment with IVIg. However, despite these treatment efforts, the majority of patients with refractory MG continued to present symptoms that had an impact on activities of daily living at the time of data analysis, although the percentage of patients with moderate or severe involvement according to the MGFA classification did decrease over the study period. While we did not specifically measure disease impact using quality of life scales, we would expect these patients to present considerable difficulties in social and mood-related domains, in addition to their physical limitations.11 Despite the limitations related to the small sample size, our results coincide with those of previous studies, and demonstrate the difficulty of managing refractory MG.

By definition, refractory MG is a chronic, progressive, disabling disease that is likely to require more aggressive treatment to prevent exacerbations, which are generally severe. However, there is a lack of consensus regarding its management in the current clinical guidelines for the treatment of MG.8,12Rituximab is often recommended,13 although this drug is mainly effective in patients with generalised anti-MuSK–seropositive MG.14 Some recommendations, such as the long-term use of IVIg as a maintenance therapy in refractory MG, present a low level of evidence.12 IVIg can mitigate and control symptoms, but has not been shown to be efficacious for inducing complete remission of the disease.15 Other treatment options for refractory MG have an even lower level of evidence. These include PLEX12 and etanercept,16 which have been associated with a clinical improvement in small case series, and cyclophosphamide,17 which has achieved long periods of remission in small series of patients with refractory MG, but whose use is limited due to its safety profile.

New treatment strategies developed in recent years target different mechanisms of the immune cascade that give rise to antibody production in MG, in an attempt to move away from conventional immunosuppressive therapy and search for more efficacious drugs.18 In this context, eculizumab is the first drug approved for the treatment of anti-AChR–seropositive MG.19 This humanised IgG2/4κ monoclonal antibody binds specifically to complement protein 5, inhibiting terminal complement activity. In refractory MG, terminal complement activation promotes anti-AChR–mediated destruction of the motor endplate, resulting in neuromuscular transmission failure. Such other drugs as bortezomib (a proteasome inhibitor)20 and belimumab (a B-cell activating factor inhibitor)21 are being evaluated in clinical trials of patients with refractory MG. However, once we establish the usefulness of these drugs, the majority of which are monoclonal antibodies, we will also need to consider when they should be administered (ie, at early stages of progression or after MG becomes refractory).

In conclusion, despite the different treatments currently available for MG, a considerable percentage of patients do not respond to conventional treatment, which has severe repercussions for their quality of life. The management of these patients is challenging, and there is a need to define new clinical and serological markers for the early identification of refractory MG, as this group of patients stand to benefit the most from the new treatment strategies that will soon be available for the treatment of this autoimmune disease.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.