Immune alterations may be the cause of some of the epilepsies considered to date to be cryptogenic, and they usually respond to immunotherapy. Some of the clinical features of this type of epilepsy are a personal or family history of autoimmune or neoplastic disease, subacute onset with high seizure frequency, multiple seizure foci, early resistance to antiepileptic drugs, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and in some cases rapidly progressive cognitive impairment.1 Presence of signs of inflammation in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies and the detection of antineuronal antibodies may help establish diagnosis.2 Diagnosis and early treatment may have a crucial impact on seizure control and cognitive comorbidity.3,4 We describe the cases of 3 patients with adult-onset focal epilepsy. Psychiatric symptoms and dysautonomia led to the suspicion of autoimmune aetiology, which was confirmed by antibody tests.

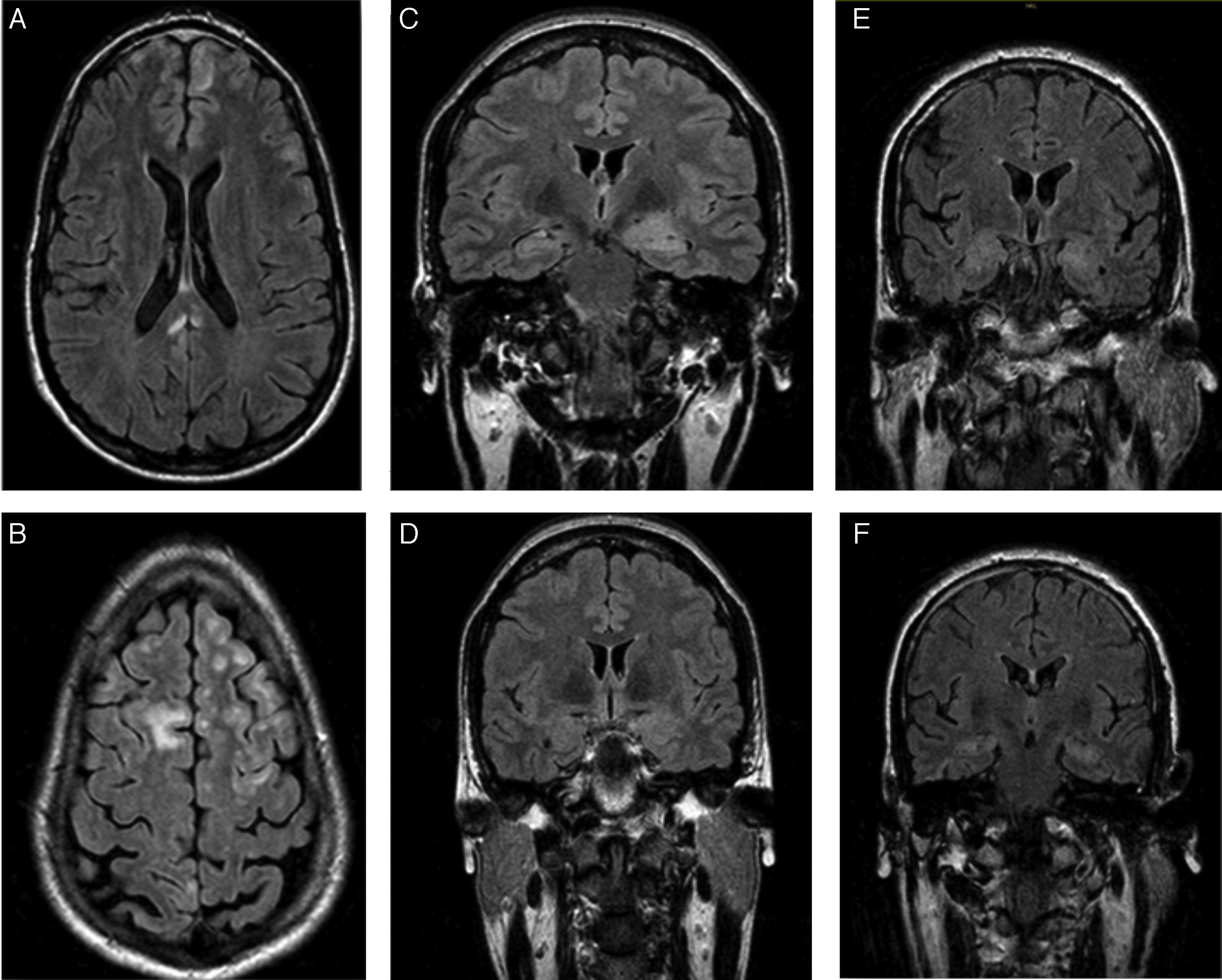

The first patient was a 24-year-old man with no relevant personal history who experienced an epileptic seizure with head version to the left, disorientation, and generalised rigidity and postictal period. Two weeks previously, he had presented behavioural alterations, insomnia, and auto- and hetero-aggression which progressed to mutism and catatonia. He also presented self-limiting episodes of profuse sweating. No paroxysms were observed in the EEG. A brain MRI scan (Fig. 1A and B) revealed hyperintensities in the frontal lobe bilaterally and in the posterior corpus callosum, with no contrast uptake. CSF and serum analyses confirmed the presence of anti-NMDA receptor antibodies (qualitative study) and tumour screening ruled out occult neoplasm. He received antiepileptic treatment during hospitalisation, as well as treatment with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants (cyclophosphamide and rituximab). A follow-up MRI scan showed that the size of the lesions had decreased. Psychiatric symptoms improved 2 weeks later, and the patient was discharged, presenting no further epileptic seizures and without receiving treatment. A follow-up laboratory test at one year showed negative results for serum anti-NMDA receptor antibodies.

Patients’ brain MRI scans. A and B) FLAIR sequence of the first patient, revealing bilateral frontal subcentimeter lesions and a T2-hyperintense lesion in the posterior corpus callosum with no contrast uptake. C and D) Diagnostic and follow-up FLAIR sequences of the second patient, showing enlargement and increased signal in the amygdala and left hippocampal head, and a subsequent decrease in size and signal. E and F) Diagnostic FLAIR sequence of the third patient, showing increased signal in both hippocampi.

The second patient was a 35-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, vitiligo, and anxiety disorder of one year's progression, under follow-up with the psychiatry department. The patient responded poorly to benzodiazepines. She had fallen and lost consciousness on 3 occasions, which had been interpreted as syncope. The patient subsequently experienced complex partial seizures with symptoms of temporal lobe epilepsy in the dominant hemisphere, with piloerection, brief episodes of disorientation, jaw automatisms, and motor aphasia. These symptoms manifested daily for one year. Baseline brain MRI results were normal. Neuropsychological tests revealed difficulty performing verbal and visual memory tasks. After receiving 2 drugs in monotherapy, she continued experiencing seizures 2-3 times per week. She was admitted to the long-term continuous video-EEG monitoring unit, and experienced 74 seizures with symptoms of left anteromedial temporal lobe epilepsy. Interictal findings were located in the anteromedial region of the left temporal lobe. A second MRI scan revealed enlargement and hyperintensity of the amygdala and left hippocampal head (Fig. 1C). Presence of anti-LGI1 antibodies in the plasma was confirmed (levels of 275 pM; normal range: negative). Treatment with corticosteroids was started and seizures disappeared after 3 weeks. The patient was treated with oxcarbazepine for one year. A follow-up brain MRI scan (Fig. 1D) showed decreased severity of the findings in the initial scan; a new plasma study confirmed negative results for anti-LGI1 antibodies. Results from the neuropsychological study performed at one year were normal. The patient is currently receiving no treatment and remains asymptomatic.

The third patient was a 62-year-old man with no relevant personal history, who was admitted due to a 2-month history of apathy and episodes of disorientation with behavioural alterations and visual hallucinations. He concomitantly presented complex partial seizures with head version to the right and generalised rigidity. During admission, he presented 5 episodes of vasovagal syncope. The video-EEG recording showed interictal paroxysms in the left temporal lobe. The brain MRI scan and laboratory tests (vitamin B12, pholate, TSH, 14.3.3 protein, tumour markers, and serology and autoimmune tests) yielded normal results. A second brain MRI scan (Fig. 1E and F) revealed increased signal intensity in both hippocampi; serum tests confirmed the presence of anti-LGI1 antibodies (levels of 188 pM). The tumour screening ruled out occult neoplasm.

Lamotrigine was administered, achieving no positive response, and was substituted with lacosamide. After autoimmune aetiology was confirmed, corticosteroid treatment was started; this resolved the symptoms. The patient died 2 months later due to respiratory infection with Pneumocystis jirovecci.

A lack of typical clinical manifestations of autoimmune encephalitis may delay diagnosis.4 Epileptic seizures in isolation are rare in autoimmune epilepsies. In our series, psychiatric manifestations and dysautonomia5 were key symptoms leading to the diagnosis of autoimmune aetiology.6,7 CSF determination of antibodies, exclusion of other causes, and negative tumour screening results for occult neoplasm helped diagnose the aetiology. Up to 50% of cases of autoimmune encephalitis respond to first-line treatment with corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, or immunoglobulins. The remaining 50% respond to cyclophosphamide and/or rituximab. Early immunological treatment is associated with a better response and may prevent progression to cognitive impairment. The time lapse between symptom onset and treatment onset is greater in refractory cases than in responding patients.4,8

Psychiatric manifestations and dysautonomia associated with epileptic seizures may be signs permitting diagnosis and early treatment of autoimmune epilepsies.

FundingThis study received no public or private funding.

Please cite this article as: Abraira L, Grau-López L, Jiménez M, Becerra JL. Manifestaciones psiquiátricas y fenómenos disautonómicos en el comienzo de epilepsia focal del adulto. Señales clínicas de un origen autoinmune. Neurología. 2018;33:412–414.