One of the current challenges in Parkinson's disease (PD) and other movement disorders (MD) is how and when to apply palliative care. Aware of the scarce training and implementation of this type of approach, we propose some consensual recommendations for palliative care (PC) in order to improve the quality of life of patients and their environment.

Material and methodsAfter a first phase of needs analysis through a survey carried out on Spanish neurologists and a review of the literature, we describe recommendations for action structured in: palliative care models, selection of the target population, when, where and how to implement the PC.

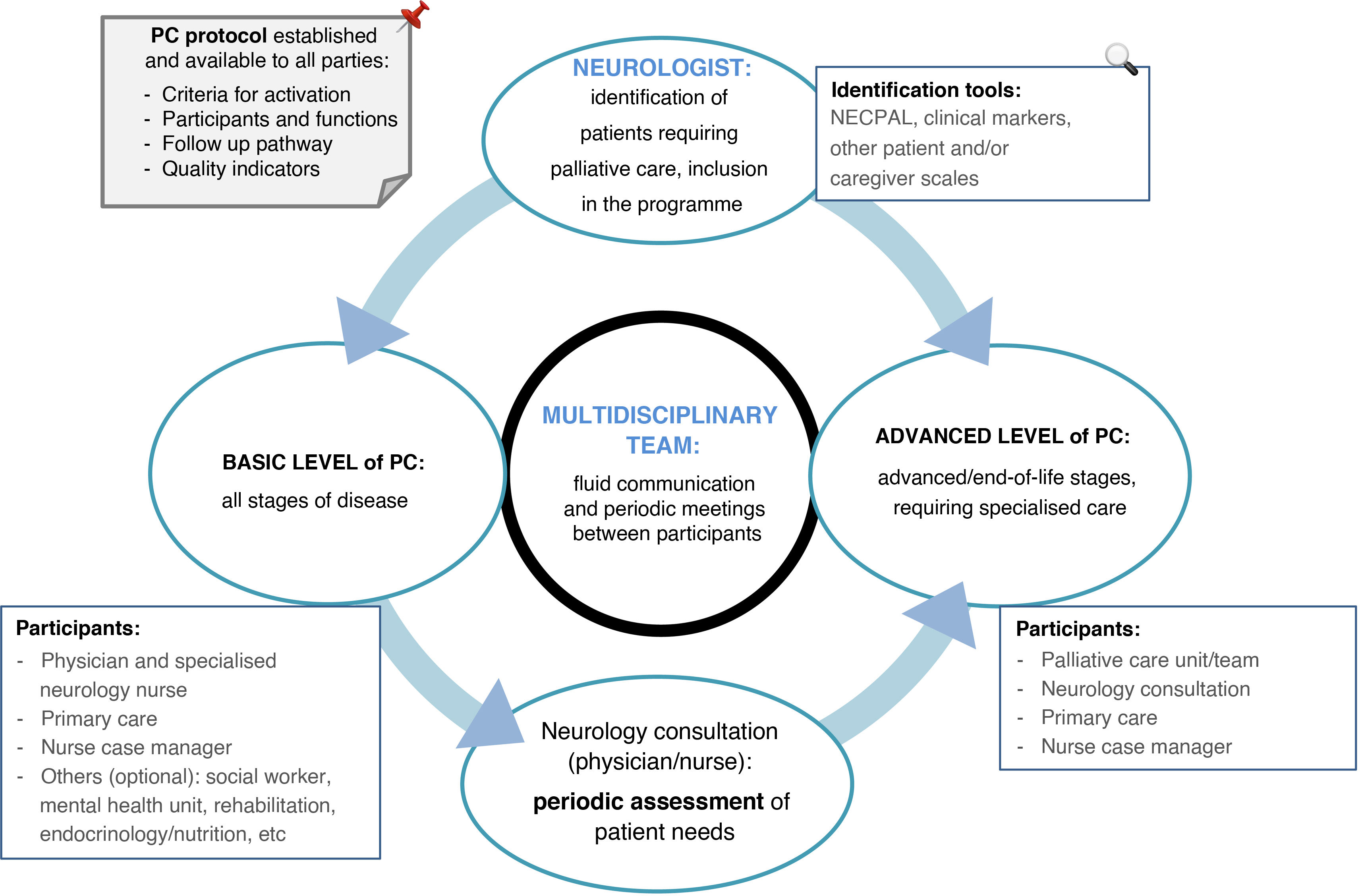

ResultsModels of neuropalliative care are reviewed, advocating for the role of the neurologist as a driving force. The members of the multidisciplinary team are described, as well as the main clinical markers and tools that help the clinician to decide which patients have greater palliative needs; sender and receiver are defined and it is detailed in what evolutionary moment and how to proceed when sending the patient to palliative care. A scheme of steps to follow in any PC protocol, whether basic or specialized, is provided, emphasizing the framework in the shared planning of care and the comprehensive approach.

ConclusionsIt would be desirable to integrate the PC in the management of PD and other MD and to validate models of neuropalliative care in our environment, analyzing their usefulness through the use of indicators, in order to improve the care and quality of life of our patients.

Uno de los retos actuales en la enfermedad de Parkinson (EP) y otros trastornos del movimiento (TM) consiste en cómo y cuándo aplicar la atención paliativa. Conocedores de la escasa formación e implementación de este tipo de abordajes planteamos unas recomendaciones consensuadas de cuidados paliativos (CP) con el fin de mejorar la calidad de vida de los pacientes y su entorno.

Material y métodosTras una primera fase de análisis de necesidades mediante encuesta llevada a cabo a neurólogos españoles y revisión de la literatura, describimos recomendaciones de actuación estructuradas en: modelos de atención paliativa, selección de población diana, cuándo, dónde y cómo implementar los CP.

ResultadosSe revisan modelos de atención neuropaliativa, abogando por el papel del neurólogo como figura impulsora. Se describen los integrantes básicos del equipo multidisciplinar, y los principales marcadores clínicos y herramientas que ayudan al clínico a decidir qué pacientes tienen mayores necesidades paliativas; se define emisor y receptor y se detalla en qué momento evolutivo y cómo proceder al enviar al paciente a cuidados paliativos. Se aporta esquema de pasos que seguir en cualquier protocolo de CP, sean básicos o especializados, enfatizando el encuadre en la planificación compartida de los cuidados y el abordaje integral del paciente y su entorno.

ConclusionesSería deseable integrar los CP en el manejo de la EP y otros TM y validar modelos de atención neuropaliativa en nuestro entorno, analizando su utilidad mediante el uso de indicadores, con el fin de mejorar la asistencia y calidad de vida de nuestros pacientes.

Parkinson’s disease (PD), atypical parkinsonism (AP), Huntington disease (HD), and other movement disorders (MD) are chronic diseases that are frequently associated with dependence, frailness, and multimorbidity. Quality care for these patients requires understanding of clinical, ethical, and organisational issues in order to respond as effectively as possible to their needs, particularly in the final stages of the disease. One of the greatest current challenges in PD management is establishing how and when to raise the issue of palliative care (PC), which has been demonstrated to improve quality of life and to relieve caregiver burden in PD.1,2

One of the strategic objectives of the Spanish National Health System is to improve the provision of PC.3 However, progress in PC for neurodegenerative diseases is slower than desired. For instance, the results of the recent survey of MD experts in Spain4 revealed a lack of specific PC protocols for MD, and a shortage of specialised nurses. Furthermore, the study found a clear lack of training in PC, with nearly all neurologists responding that they lacked sufficient training in this field; all respondents, without exception, identified the implementation of PC protocols for these diseases as a priority need.

The need to improve PC in neurodegenerative diseases is even more pressing in the light of the recent adoption of the Organic Law for the Regulation of Euthanasia (LORE, for its Spanish initials).5 Aware of the limited implementation of PC in our setting and the crucial need to improve it as part of the care provided to patients with advanced and terminal diseases, the Ad hoc Committee for Humane Care at the End of Life of the Spanish Society of Neurology (SEN) recently published a position statement on the LORE,6 proposing a series of resources and needs for humane end-of-life care for patients with neurological diseases, structured around 5 lines of action: 1) visibility; 2) training; 3) organisation of neuropalliative care; 4) coordination and integration of existing PC resources, and 5) knowledge creation.

This document proposes a road map for PC, with a view to encouraging and helping clinicians to implement PC for patients with MDs at their work centres. The ultimate goal is to improve care and quality of life for these patients and their families.

MethodsIn an initial phase, a working group was created that included specialist neurologists and nurses specialised in MDs and PC, with a view to analysing the current situation of PC in patients with MDs in Spain and suggesting improvements. To that end, we performed a literature review and conducted a survey of neurologists attending patients with MDs, addressing the care provided and the application of PC; the findings of that exercise were published in December 2021.4 In this second stage of the project, in accordance with the timeline established, we expanded the literature search on PubMed and the review of clinical practice guidelines and publications from the most relevant scientific societies. This article develops the main points to be included in any PC model applied to patients with MDs, with a view to addressing the shortfalls identified in the initial survey and ultimately improving the care and quality of life of these patients and their families.

A complete discussion of PC in neurodegenerative diseases, from a review of basic concepts to the full complexity of the subject, is beyond the scope of this article. Focusing on practical matters, we developed the following approach: first, how care should be organised and who should be responsible for its implementation; subsequently, how to identify the patients with greatest potential to benefit; and finally, having identified the care provider and recipient, the details of how to proceed. The process may be summarised in 5 steps: 1) models of PC in MDs; 2) target population; 3) timing; 4) care setting; and 5) implementation of PC. Table 1 reviews the basic concepts for understanding the PC approach.

Basic concepts in palliative care.

| Palliative care: an approach that improves quality of life for patients and families facing the problems associated with life-threatening diseases. This approach focuses on the prevention and relief of suffering using early identification and strict evaluation and treatment of pain and other physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems. |

| Advance or shared healthcare planning: a structured, deliberative, relational process that enables reflection and understanding of the experience of disease and the associated care among the persons involved, with a focus on the patient, who should be able to identify and express their preferences and expectations about the management of their disease. It includes the following steps: preparation, proposal, dialogue, validation, registration (in the medical record), and re-evaluation. This process is also referred to as care planning. |

| Advance healthcare directives or living will document: a document aimed at physicians, in which legally competent elderly patients may freely express the instructions to be taken into account when they are in a situation in which they are unable to express their wishes, always in accordance with the law. The document may be completed before a notary or witnesses, at hospital or the health centre. |

| Nurse case manager, link nurse, or advanced practice nurse: a professional who assists patients in accessing all health and social care services required to meet their needs. This prevents duplication of work and improves the quality and effectiveness of clinical outcomes. Their specific functions vary according to the model and needs of each healthcare centre or system, and they are a key figure in the care of patients with chronic diseases, with high demand for complex care and resource use. |

At least 3 models have been described for the implementation of PC/MDs,7 with each model presenting its own advantages and disadvantages. The first of these is based on PC specialists, either in a specific consultation or as part of a multidisciplinary team. The second model is fundamentally based on neurologists, who implement PC within the framework of their own clinical practice. The third model, which is novel and is not yet available in our setting, is based on neuropalliative care specialists with experience and training in both neurology and PC. The latter 2 models are centred around the figure of the neurology specialist, which provides an additional benefit as these professionals have extensive knowledge of the disease, an established physician/patient relationship, and ultimately may better predict prognosis and identify changes in symptoms or disease progression.7 Whoever is responsible for initiating or providing PC, it is crucial that this care follows a multidisciplinary approach including specialists from other branches of medicine, healthcare, and nursing, which are key to the proper design and functioning of the system. In our setting, in view of the organisation of healthcare and the figure of the neurologist as the professional who accompanies the patient throughout their disease, we advocate for the model focusing on the neurologist as the driver and coordinator of PC.

What is the target population for palliative care?The target population includes patients with PD and other MDs, and especially AP and HD. They are generally patients with complex diseases and different care needs, including the need to integrate PC with symptomatic care and curative care (if any) during part of the disease course.

The palliative approach in these patients may provide numerous benefits. Clinicians must prioritise basing care on the multidimensional needs of the patient and their family, rather than on a concrete expected survival time, the approach followed in PC for cancer, for instance. While prognostication is fundamental to decision-making, it is one of the greatest challenges facing healthcare professionals in these diseases. The prognosis-centred model, which includes consideration of such questions as “would I be surprised if my patient died within one year?,” is widely used by PC physicians and may be used to complement the assessment of unmet needs, particularly if we seek to focus PC on more terminal stages. In this regard, the Palliative Needs (NECPAL, for its Spanish abbreviation) instrument8 is a widely used tool for the assessment and screening of palliative needs in chronic disease, including neurodegenerative disease. In addition to the aforementioned “surprise” question, it includes 3 dichotomous (yes/no) questions: 1) choice or demand for PC; 2) presence or absence of general indicators of severity; 3) presence or absence of specific indicators. Patients are considered NECPAL-positive (ie, in need of PC) if they are positive for the surprise question (“I would not be surprised…”) and for one additional item.

Although there are no specific tools for determining PD/MD prognosis on an individual basis, particularly in the context of advanced age and diverse comorbidities, we do have specific markers of advanced disease and mortality,9 such as: dementia and hallucinations, older age, longer disease duration, more advanced Hoehn and Yahr stage, weight loss, dependence as measured with the Schwab and England scale or the Barthel Index (validated for both ON and OFF state in PD10), frequent infections (mainly pneumonia) or hospitalisation, pressure ulcers, malnutrition, and functional deterioration. This can be measured with such tools as the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS),11 an instrument that was initially designed for oncology, which enables measurement of the progressive decline of palliative patients, detecting the transition towards death; the patient’s general condition is classified into 11 descending categories from 100% (normal) to 0% (death).

Patients with HD largely share the same markers of mortality. In the case of HD, it should be noted that the cause of death is suicide in up to 6.6% of cases12; therefore, we should be alert to possible suicide attempts or severe mood disorders.

In recent years, a growing number of studies have aimed to identify the factors that represent the greatest burden for patients with PD and their families.13 Particularly relevant are non-motor symptoms, especially depression, psychosis, and uncontrolled pain, which can worsen patients’ quality of life.14 The lack of day-to-day support, living alone, lack of social integration, and financial difficulties are also important factors to take into consideration, given the concern they can cause for patients with advanced PD.15

Partly due to their advanced age, multimorbidity is common in patients with PD and other MDs, and increases their care needs and the risk of mortality. The PROFUND index16 is the most relevant prognostic tool for polypathological patients, and is helpful for selecting patients with greater PC needs. The risk of mortality at 12 months is stratified into 4 groups (low, medium, high, and very high), as a function of patient age, clinical characteristics, analytical parameters, and functional/socio-familial variables.

In addition to clinical markers, recent years have seen the adaptation and validation of various instruments previously used for oncological patients, which enable more objective identification of patients requiring PC. Some tools not only identify and quantify care needs, but also enable assessment of changes in response to interventions. It is important to be aware of some of the limitations of these instruments: although they have been validated in patients with PD, none of these studies was conducted in a Spanish population; furthermore, they may overburden the consultation, hindering their implementation in everyday practice. The most appropriate tool to use in each case will depend on a range of factors: where PC will be provided, characteristics of the patient and their family, stage of disease progression, structure and organisation of the department, and the material and human resources and time available.17

Tables 2 and 3 summarise the main clinical factors and assessment tools, respectively, that may help in identifying patients with MDs who are eligible for PC.18–23 It is the responsibility of each clinician and/or centre to determine how many items and which tools to use for selecting their target population, according to the stage of disease progression at which PC is implemented and the time and resources available. For instance, if the available resources are limited, it may be more effective to focus on patients with greater needs, and therefore presenting several markers (Table 2); on the other hand, if we wish to provide this care to a broader range of patients, then presenting a single marker and/or NECPAL positivity may be considered sufficient.

Main clinical markers for the implementation of palliative care in movement disorders.

| Dependence (Barthel index < 35) |

| Functional impairment |

| Repeated falls |

| Persistent dysphagia |

| Marked weight loss and/or need for PEG |

| Pressure ulcers |

| Recurrent infections or hospitalisations in the previous year |

| Uncontrolled pain |

| Dementia |

| Confusion |

| Uncontrolled depression and/or behavioural alterations |

| Social isolation and/or caregiver burnout |

PEG: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

Tools for evaluating the need for palliative care in Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders.

| Tool | Validated in | Completed by | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| POS-S-PD19,20 | PD and APHY 3-5 | Patient and/or caregiver | Assesses 20 items (difficulty moving arms and legs, fatigue, sialorrhoea, daytime sleepiness, nausea, pain, difficulty communicating, cramps, constipation, insomnia, anxiety and depression, urinary urgency and incontinence, dysphagia, and dyspnoea) |

| ESAS-PD21 | PDDisease stage not defined | Patient and/or caregiver | Assesses 14 items: 10 general and 4 specific to PD (constipation, dysphagia, rigidity, and confusion). Helpful for measuring treatment response |

| PACA18 | PDHY 1-5 | Patient | Assesses 10 motor and non-motor symptoms perceived as the problems with the greatest impact on quality of life (particularly immobility, pain, insomnia, urinary tract disorders, drowsiness, and anxiety). Quick and simple to administer |

| NAT-PD22 | PDHY 1-5 | Clinician/healthcare professional | Evaluates 3 domains addressing the patient’s physical, existential, psychological, spiritual, financial, and interpersonal needs, and informs about the level of concern of each domain. The most comprehensive tool |

| NECPAL8 | Advanced, chronic disease, including PD and dementia | Clinician/healthcare professional | Positive result is defined as presence of 2 of the following specific indicators of PD severity: progressive physical and/or cognitive impairment despite optimal treatment; complex, difficult-to-control symptoms; problems with speech problems/increased difficulty communicating; progressive dysphagia; recurrent aspiration pneumonia, dyspnoea, or respiratory failure. |

| Zarit Burden Interview23 | Caregiver | Caregiver | Consists of 22 self-administered items, scored on a scale of 0-4 (total score ranges from 0 to 88 points). Higher scores indicate greater burden. |

AP: atypical parkinsonism; ESAS-PD: Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; HY: Hoehn and Yahr stage; NAT-PD: Needs Assessment Tool Progressive Disease; PAL: Palliative Needs tool; PACA: Palliative Care Assessments; PD: Parkinson’s disease; POS-S-PD: Palliative Outcome Scale for Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease.

Caregiver burden should always be taken into account when assessing the need for PC. One of the most widely used scales is the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), which has been validated for PD and has an established cut-off point for significant burden.23

When?PC models have classically been presented as dichotomous, with the mutually exclusive options of curative or symptomatic treatment in early stages, and PC only once the previous measures are no longer effective; this sometimes required the patient to choose between these options. This concept has evolved over time, with a new model of simultaneous care that focuses on improving quality of life from early stages of the disease and not only in final stages24; this also encompasses strictly medical issues as well as any unmet emotional/spiritual needs of the patient and of their caregiver/family.

Little evidence is available on when is the most appropriate time to formally initiate PC in patients with PD and other MDs. In addition to differences between countries in healthcare organisation, the complexity and heterogeneity of these diseases also contribute to the difficulties in establishing a consensus approach to PC. Despite this, instruments are available to help in the early identification of patients with greater needs, as noted in the previous section; this requires organisation, defining the target population, and creating the necessary structure in accordance with the characteristics of each centre. In this respect, given the shorter life expectancy and earlier and more predictable onset of complications, patients with AP (multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration), and possibly those with HD, may be included from early stages of progression, whereas a plan can be established later in PD, based on the detection of markers or guide signs described.

In general, we may note a series of key points in the PC process for these diseases:

Initial stages, close to the time of diagnosis: informing patients about the disease and prognosis, treatment options, and non-pharmacological recommendations, and integration of the shared care planning process.

Intermediate stages: advancing in the shared care plan and informing patients about the possibility of completing the advance healthcare directives document before their ability to make decisions is affected.

End of life or disease end-stage with more complex needs: implementation of advance directives or measures agreed by patients and their families, and creation of an action plan for specialised PC (see below).

PC may be administered at a basic level (settings without specialisation in PC) or a specialised level (PC specialised centres).25,26 According to patient needs, this care may be provided in the home, at outpatient consultations, or with inpatient hospitalisation:

- -

The basic (primary, general) level of PC includes the methods and procedures performed at non-specialised centres. This level of care is provided at all stages of disease progression: symptom control, communication with patients and their families, decision-making, and goal-setting in accordance with patient needs. In other words, it involves shared care planning or decision-making, which requires a shift from the classical paternalist model to a new approach focusing on the patient’s autonomy and right to participate in clinical decision-making.

Neurology consultations should routinely provide this basic level of PC, in collaboration with other professionals and/or departments (see below). Primary care plays a fundamental role in this type of PC, and is an essential agent in the early management of symptoms and follow-up at home.

- -

Specialised (advanced) PC is generally provided to patients with complex needs, and preferably requires a multidisciplinary team or professionals with official training in specialised PC, whose practice is exclusively dedicated to this field. This care may be provided through outpatient consultations, hospitalisation, or in the home. At this level, it is even more important to ensure fluent communication between actors, with care ultimately being provided by the hospital and home palliative care unit or team. If specialised teams are not available, the neurologist, working in collaboration with nurses and any other professionals needed, may provide this advanced care on an individual basis.

After identifying the target population and its main needs, another key question is how PC should be provided. The steps described below are summarised in Fig. 1. However, the organisation of each healthcare centre/system is the most important consideration. The system must take a multidisciplinary approach.28–30 It is essential that agile, effective means of communication are in place, and that protocols are reviewed by all stakeholders. The protocol defined by each centre, with its criteria for activation and follow-up, participants, and communication systems, should be recorded (in writing and/or digitally) and made available to all parties.

The steps for implementing PC in this population are:

- 1.

Defining and identifying the patient at the neurology consultation (target patient).

- 2.

Including the patient in the PC pathway (basic or specialised).

- 3.

Identifying the healthcare district/health centre/primary care physician responsible for the patient.

- 4.

Identifying and defining the primary caregiver, or lack thereof.

- 5.

Periodic assessment of the patient’s situation to identify the objectives achieved, new incidents, and the need for specialised PC.

- 6.

Periodic meetings between the participating healthcare services, for: joint case assessment, addressing issues in the care pathway, and promoting improvement measures.

- 7.

Implementation of indicators:

- •

Percentage of the patients included in the system.

- •

Scales evaluating patient quality of life and caregiver burden.

- •

Indicators of satisfaction with the system implemented among patients, caregivers, and participating healthcare professionals.

- •

Effectiveness indicators, such as:

- •

Number of emergency department visits and reasons for visits among patients included in the programme, assessing whether any of the reasons for consultation could have been resolved by improving care under the PC plan.

- •

Number of hospital admissions and reasons for admission.

- •

Number of patients for whom shared care planning processes have been carried out, with the patient participating in healthcare decision-making.

- •

Number of patients in the programme completing advance healthcare directives documents.

- •

Number of patients in whom the decisions made by the patient were respected, in accordance with their values and preferences.

- •

We should underscore the emerging role of telemedicine in ensuring the continuity of PC in these patients,31 particularly among those living far from the healthcare centre, and in reducing the number of visits, resolving questions, etc. Furthermore, communications technologies can be a great help in interprofessional coordination and rapid resolution of issues between members of the multidisciplinary team.

Depending on the level of PC (basic or advanced) deemed most appropriate, we propose the following points and define the main roles of participating professionals26:

- A)

First-level or basic palliative care at the neurology consultation:

- 1.

Providing patients/caregivers with contact information (telephone/e-mail) for fast, effective communication with the neurology department (specialised nurses/physicians).

- 2.

Consultation with the neurologist:

- •

Periodic assessment of the patient’s situation (motor/functional/psychological/social) to identify the objectives achieved and new incidents (need for nutrition/speech therapy assessment in the event of dysphagia, or rehabilitation/physiotherapy assessment in patients with gait freezing, falls, etc).

- •

The neurologist is responsible for referral to other specialties and/or professionals, according to patient needs. This may include primary care, health centre/hospital nurse case manager, and the relevant services, depending on patient needs: rehabilitation, endocrinology, mental health unit, social work, speech therapy, etc.

- •

Periodic assessment of the need for specialised PC.

- •

Continuation of the communication process/shared planning of decisions, exploring the patient’s values and wishes and advancing over time with more specific decisions regarding foreseeable scenarios in the disease, including early conversations about advance healthcare directives.

- •

Palliative symptom management, including therapy simplification and deprescription of drugs and therapies if necessary, particularly in the final stages of disease. Table 4 describes the management of the most disabling symptoms in the advanced/final stages of PD and other MDs. Neurologists should also mention palliative sedation, which is classified as part of specialised PC.

Table 4.Management of particularly relevant symptoms and situations in movement disorders.

Symptom Treatment Pain Pain should always be treated, regardless of the cause. The most common cause is musculoskeletal pain due to rigidity, immobilisation, or abnormal positions.Type and intensity should be assessed with medical history interview with the caregiver or simple scales such as the VAS. Antiparkinsonian treatment should be optimised (dystonia, OFF state, etc). Drugs for neuropathic pain (gabapentin, pregabalin, antidepressants, etc) should be considered. In addition to physical/physiotherapy methods, the most suitable drugs should be selected according to the steps of the WHO analgesic ladder: step 1, non-opioids; step 2, weak opioids; step 3, strong opioids. Dementia Psychosis Screening for intercurrent factors (pharmacological, metabolic, infectious, etc). Treatment adherence should be reviewed and therapy simplified through the reduction or suspension of drugs in the following order: anticholinergics, amantadine, dopamine agonists, and MAO-B inhibitors. Efforts should be made to continue with levodopa in monotherapy due to its more favourable profile of adverse effects at this level. Rivastigmine (preferably by transdermal patch) should be considered if it is not yet included in treatment. Continuation of treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors (eg, rivastigmine) until the final stages of the disease should be assessed in patients with dementia due to their positive effect on psychotic symptoms. If antipsychotics are needed, quetiapine and clozapine are the drugs of choice due to their lower potential for extrapyramidal adverse effects. With a lower level of evidence, other drugs may be used: ziprasidone, olanzapine, clomethiazole, etc. Constipation Constipation worsens with disease progression, immobility, and certain drugs, such as anticholinergics and morphine derivatives. In addition to recommending exercise, abdominal massage, and dietary changes, it is always helpful to suspend or switch any drugs that may be exacerbating this symptom. The main dietary recommendations are: 1) increasing hydration; 2) adding fibre-rich foods, and yoghurt or kefir, which contain pre- and probiotics; and 3) reducing intake of fatty foods, coffee, alcohol, flour, and refined sugars. Dietary supplements such as wheat bran and linseed, which favour intestinal transit, may also be considered. If laxatives are needed, the recommended drugs in PD are oral osmotic laxatives, such as macroglol (1-3 sachets per day) and lubriprostone (in capsules; not commercially available in Spain). In refractory cases, rectal osmotics may be used in micro-enemas or larger enemas, or deimpactation may be performed with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, with monitoring for potential vagal reactions. The use of intrasphincteric botulinum toxin or surgery (internal sphincter myectomy and/or sphincterectomy) is very rare, and is restricted to severe cases. Dysphagia Dysphagia is associated with weight loss and aspiration of food and/or saliva, increasing the risk of pneumonia. Dietary modifications should be made in response to dysphagia onset/progression: texture, position when eating, and thickeners if needed.No specific recommendations exist on the use of nasogastric or PEG feeding in patients with PD and other MDs. PEG may be considered in terminal cases, although this may not improve survival in patients with dementia. As a general rule, NG tubes should not be left in place for longer than 3-4 weeks. If they are needed in the terminal phase or due to intercurrent processes, it is fundamental to inform the patients and their family of the prognosis after PEG and the complications of the procedure, being sure to mention infections, recurrent pneumonia, and institutionalisation.32 Immobility Immobility may cause pain and promote constipation and pressure ulcers. Physiotherapy programme/repositioning. Anti-bedsore mattress and nursing recommendations to prevent ulcers. Evaluate the use of botulinum toxin for extreme rigidity causing pain and/or hygiene problems. Palliative sedation Palliative sedation consists in intentionally decreasing the patient’s level of consciousness through the use of appropriate drugs, in order to prevent intense suffering caused by refractory symptoms. This approach seeks to relieve the patient’s physical and psychological suffering by avoiding futile interventions, to promote the companionship of their loved ones, to attend the family, and to value the spiritual needs of the patient and their caregivers. It may be administered in the “last days of life,” the state preceding death in those diseases in which life gradually fades, or the state of pain, struggle, and suffering that many people experience before death. During the process, decisions must be based on consensus, in line with the objectives established. Therapy simplification will be prioritised, with a preference for subcutaneous administration, particularly if venous access is difficult or if the patient is at home. The drugs of choice, in order of preference, are: benzodiazepines (midazolam), sedative antipsychotics (chlorpromazine or levomepromazine), antiseizure medications (phenobarbital), and anaesthetics (propofol). In patients with delirium, levomepromazine is preferable to midazolam. MAO-B: monoamine oxidase B; MD: movement disorder; NG: nasogastric tube; PD: Parkinson’s disease; PEG: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; VAS: visual analogue scale; WHO: World Health Organization.

- •

- 3.

Consultation with the specialist nurse:

- •

Discussion about the intervention as a whole, from the general to the specific, and consensus on basic care to improve patient quality of life.

- •

Assessment at different stages of disease, and planning of treatment in advance, in order to tailor care to the patient’s needs by health pattern over the course of the disease.

- •

Health patterns: respiration, mobility and fall prevention, feeding/prevention of aspiration and adequate hydration, excretion, skin hygiene and integrity, sleep, clothing, communication of emotions and behaviour, leisure, self-realisation, and adaptation to change.27

- •

The nurse must be a reference for patient care involving different disciplines and participants to comprehensively meet the needs of patients and their caregivers.

- •

- 4.

Primary care:

- •

Neurologists will contact the primary care physician, either directly or through the nurse case manager, depending on the circumstances. The primary care physician must be provided with a means of fast, effective communication to resolve and report any incidents or the patient’s future needs.

- •

The primary care physician will notify the primary care nurse of the patient’s presence and inclusion in the PC system, and advise social services to assess the patient’s situation and initiate any necessary bureaucratic procedures.

- •

The nurse case manager plays a key role, acting as a liaison between primary and specialised care.

- •

- 1.

Each centre should evaluate the possibility of electronic and/or telephone interconsultation between professionals, whichever is most agile and convenient.

- B)

Specialised palliative care

At this level, PC is provided by a team that typically includes specialist physicians, nurses, psychologists, and social workers with specific training in PC. Given the limited time typically available to clinicians, and with a view to optimising resources, in our setting, we may consider restricting this specialised care to patients with more complex diseases and greater needs (end-stage PD/HD and AP), who are likely to benefit from a more intensive, multidisciplinary approach.

This care aims to examine and to intensify the treatment of the physical symptoms that appear (Table 4), to provide psychological care to help patients live with the lowest possible level of emotional distress, particularly in the final stages of the disease, to attend to their spiritual needs, and to help prepare their farewell and will. In summary, these specialists accompany the patient, respecting their values and anticipating foreseeable situations to enable calm decision-making, avoiding situations of crisis wherever possible. The patient and family are considered as a whole in care provision, working with conspiracy of silence, if this exists, and preventing pathological grieving and promoting the resolution of outstanding issues. After the death of the patient, PC specialists continue attending the family through the grief stage.

In this scenario of specialised PC, we propose:

- 1.

Providing patients/caregivers with contact information (telephone/e-mail) for fast, effective communication with the PC unit and neurology department (nurses/physicians).

- 2.

Neurology consultation (physician and nurse):

- •

Performing interconsultation with the PC team or unit and providing consultation to this team.

- •

Periodically evaluating the patient (electronically or by telephone) to identify the objectives achieved and new incidents, and continuing communication with the patient/caregiver.

- •

- 3.

Specialised PC unit/team: making initial contact with the patient alongside their neurologist; this provides a sensation of continuity of care and increases trust in the patient and their family.

- •

Hospital unit: a) outpatient follow-up consultations; and b) in the hospitalisation phase: intercurrent diseases, whether secondary to the underlying disease or not, with particular attention at the end of life.

- •

Hospital-at-home unit: a) intervention for intercurrent diseases; and b) attention, support, and companionship at the end of life.

- •

- 4.

Primary care and the nurse case manager will offer support to the patient and primary caregiver.

- •

Comprehensive palliative care of MDs is an unmet need, as has been noted by specialists in MDs in our setting4; this article aims to clarify concepts, help to correctly identify eligible patients, and lay the path for the implementation of PC. The modern conception of PC supposes the inclusion of increasing numbers of patients with complex, chronic diseases who would benefit from multidisciplinary management. In all likelihood, not all patients will have access to specialised PC teams, but will benefit from a palliative approach to their care at all levels of healthcare; it would be unethical not to offer this care, particularly in the final stages of disease.

In addition to designing the structure and the agents involved in this care, it is crucial to implement advance healthcare planning, which will largely avoid suffering and unnecessary use of resources, such as undesired hospital admissions. This care planning process is particularly important in PD and other MDs, as these patients’ higher brain functions are often impaired over time; the failure to discuss and anticipate certain foreseeable situations leads to the occurrence of complex, difficult-to-manage situations, such as deciding whether or not to provide artificial feeding to a terminally ill patient, among others. In this respect, one of our objectives must be to increase the number of patients who complete the advance health care directives document. Although it has been over a decade since the publication of legislation and the first recommendations on the creation of these documents in our setting, in reality their implementation remains poor. According to official sources, a total of 336 329 documents were registered in Spain in 2021, equivalent to 7.71 per 1000 population.33 An upward trend has been observed since the implementation of synchronised registries between autonomous regions, though there remains room for improvement; neurologists play a fundamental role in encouraging patients to complete these documents, clarifying any uncertainties that may arise at any time. Nonetheless, we must bear in mind that these documents cannot replace communication between the patient and healthcare professionals. Advance healthcare directives should be understood as one part of the process, with a focus on the story of the patient’s values, rather than on the document, in order that, as representatives and professionals, we are able to correctly interpret it when the time comes.34

In this regard, numerous challenges lie ahead. According to the proposals of the SEN’s Ad hoc Committee for Humane Care at the End of Life on the resources and needs for humane end-of-life care for patients with neurological diseases, we must:

- 1.

Improve the visibility of the palliative approach and our awareness of its importance as healthcare professionals, providing PC simultaneously with symptomatic and/or curative measures from early stages, and especially in the final stages and in complex situations of high disease burden and in which important decisions must be made.

- 2.

Prioritise improving the training of all neurologists involved, in several areas: multidisciplinary work, symptom control, therapy simplification, improving information and appropriate communication, knowing tools for assessing patient autonomy, and ultimately enabling shared planning of decisions.

- 3.

Take steps in the organisation of neuropalliative care in MDs, a necessarily multidisciplinary undertaking, and optimise organisational aspects, enabling us to adapt to distinct needs and objectives as the disease progresses. We stress the role of nurses specialised in MDs as a fundamental part of the model; currently, these specialists are only available in a small number of neurology consultations.4

- 4.

Coordinate and integrate the existing PC resources with the adaptation of protocols existing in such other diseases as cancer and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, exploiting the resources and training available at the great majority of centres.

- 5.

Create knowledge. In addition to the dissemination of the recommendations presented here, which are intended as guidelines, numerous scientific societies including the SEN and the Spanish Society of Palliative Care (SECPAL) have promoted training efforts in recent years, through the publication of clinical guidelines, the organisation of online and in-person courses, and dissemination at conferences, among other activities.25,26,35 Due to its relevance in our setting, we underscore the publication this year of a chapter dedicated to PC for patients with PD in the clinical practice recommendations of the Andalusian Study Group on MDs.36 Recently, the SEN’s Stroke Study Group became the first of the Society’s groups to publish a Palliative Care Manual,37 targeting patients with stroke; we hope that other groups will follow this line of work and publish similar manuals. Regarding the relevance of learning about PC in MDs, and in neurological disease in general, we believe that training in PC should be included in the curriculum of neurology residents, given the high prevalence of patients with diseases likely to benefit from this approach to treatment, and the known benefits of PC.

The working recommendations proposed were developed through a review of guidelines, other literature, and the authors’ experience; however, this is not a validated working protocol or model. These recommendations are intended to serve as a basis for clinicians to implement PC protocols in their centres, always taking into account the local situation and resources. It is imperative to improve training on PC in MDs and to validate neuropalliative care models in our setting, to better adapt care pathways to the needs of patients with advanced neurological diseases, and to analyse the value of these protocols using quality indicators both at the system level and the level of patients and their families; this would help us to optimise resource use and improve the care provided to this patient group.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We wish to thank the staff of the Spanish Society of Neurology, all members of the Movement Disorders Study Group, and the neurologists who completed our initial survey.