Neuroacanthocytosis encompasses a group of neurodegenerative disorders characterised by neurological symptoms and spiculated erythrocytes. One of these disorders is chorea-acanthocytosis, an autosomal recessive condition usually manifesting in the second decade of life.1 It is characterised by obsessive behaviour, impulse control disorders, infantile behaviour, cognitive impairment, seizures, high CPK levels, dystonia, chorea, and tics.2,3

Neuroacanthocytosis is associated with mutations in the VPS13A gene, which is located at 9p21.2; this gene codes for chorein, a protein found in the brain, testicles, kidneys, splenium, and erythrocytes. Chorein deficiency leads to apoptosis of striatal neurons, but the exact role of this protein is yet to be fully understood.4,5

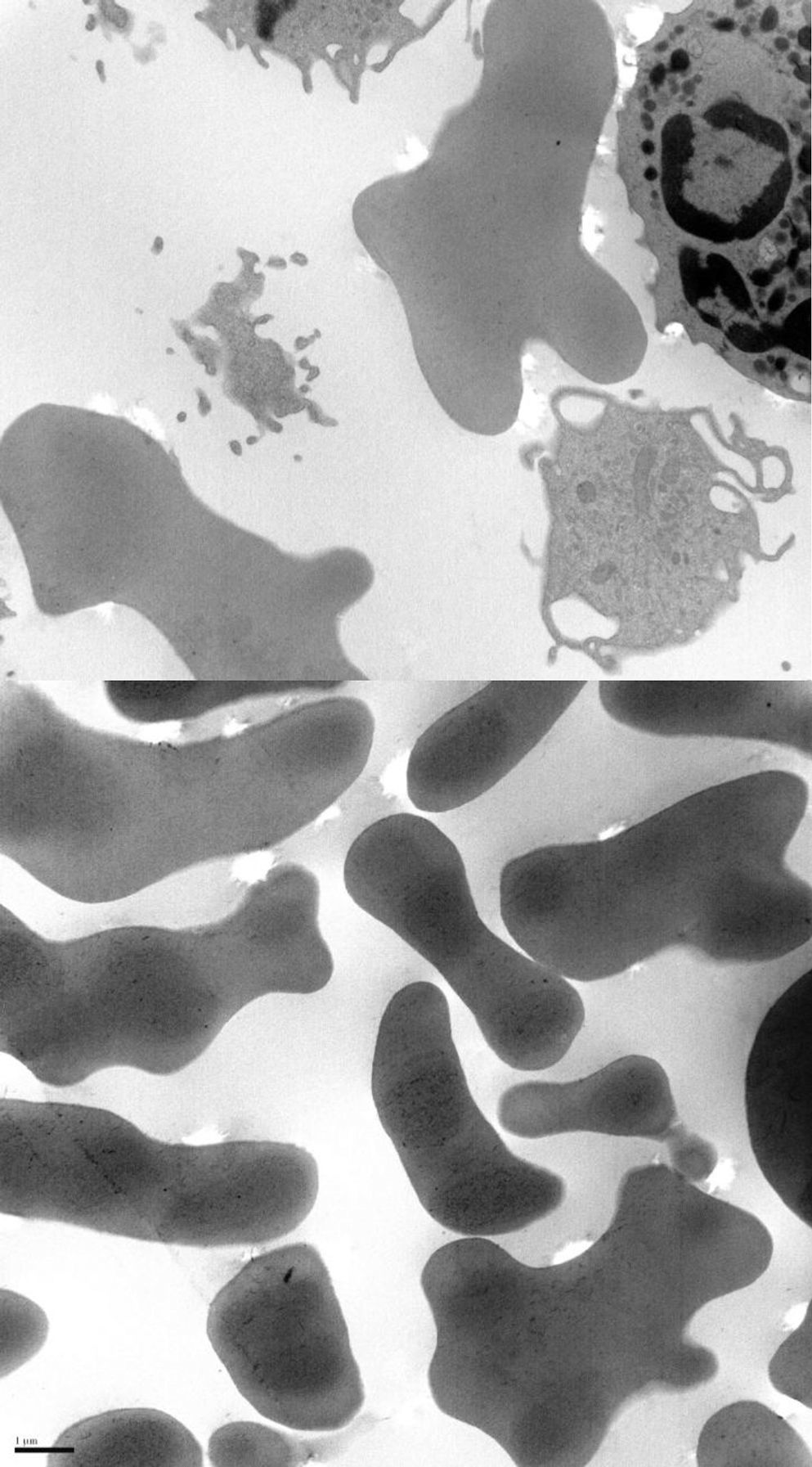

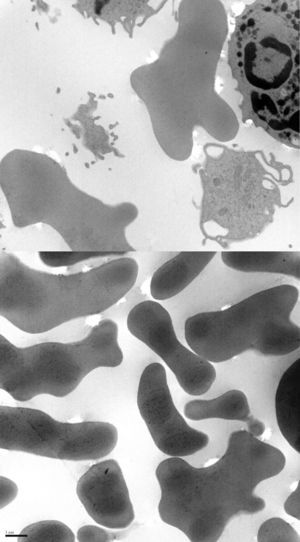

We present the case of a 38-year-old man whose psychomotor development had been normal until the age of 26, when he began to experience seizures. He had no personal or family history of interest and reported no long-term drug use. After the first seizure, he displayed extremely high CPK levels (>4000IU/L) which did not normalise between seizures (around 600IU/L). The neurological examination revealed mild dysarthria, numerous facial tics, and dystonic movements of the tongue while eating, which led to expulsion of the bolus (Fig. 1). A neuropsychological examination found no cognitive impairment, although our patient displayed infantile behaviour with increasing disinhibition and impulsiveness. A neuroimaging study revealed caudate nucleus atrophy and slightly hyperintense putamina. He was negative for the Kell antigen. Results from a neurophysiology study (EMG) were normal. No mutations were detected in the gene IT15. A blood smear requested in view of our patient's seizures, high CPK levels, tics, and lingual dystonia (associated with radiological findings) revealed presence of acanthocytes, but they were not numerous enough to be considered pathological. Due to the strong clinical suspicion of acanthocytosis, the haematology department applied the technique described by Feinberg et al.6: erythrocyte dilution in normal saline/EDTA and in vitro ageing, which drastically increases the percentage of cells developing positive signs. Longer in vitro ageing incubation time resulted in a pathological increase in the number of acanthocytes (Fig. 2). A genetic study was conducted due to clinical suspicion of chorea-acanthocytosis. The molecular study detected 2 different heterozygous mutations in the VPS13A gene. In the first mutation, C was replaced by G (c.1901-3C>G); this pathological change may affect correct mRNA processing. In the other allele, we detected a deletion of 4 nucleotides (c.9446_9449del), which presumably leads to reading frame changes and appearance of a premature stop codon (p.ILe3149Thrfs*38). Although these genetic alterations had not been described previously in the databases that we had consulted, they were very likely to be pathological. Our patient's parents underwent a genetic study, which revealed that each of them carried one of these mutations. This confirmed that the molecular alterations observed in our patient were located in different alleles; genetic changes were very likely responsible for neurological symptoms.

Chorea-acanthocytosis has a high genetic variability. In 2011, Tomiyasu et al.7 found 36 pathological mutations, 20 of which had not been described previously. Sixteen of these patients displayed complete absence of chorein in erythrocytes.

Various antiepileptic agents had been employed to manage seizures, with poor results. Following the patient's diagnosis, we administered phenytoin dosed at 150mg/8h (necessary to maintain therapeutic plasma levels); our patient has remained seizure-free ever since. The patient was treated with SSRIs, clonazepam, tetrabenazine, trihexyphenidyl, pimozide, and risperidone for behaviour disorders and dyskinesia, with no clinical improvement.

We wish to highlight that blood smears to determine the presence of acanthocytes may yield false negative results; when there is a strong clinical suspicion of acanthocytosis, the haematology department should use the Feinberg technique. In our patient, we achieved good seizure control with phenytoin, but we were unable to control movement and behaviour disorders. This patient displayed 2 previously undescribed mutations, one on each allele, which resulted in a wide array of symptoms.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Temprano-Fernández MT, Asensi-Álvarez JM, Álvarez-Martínez MV, Buesa-García C. Neuroacantocitosis, una nueva mutación. Neurología. 2017;32:197–199.