Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a syndrome frequently manifesting in obese women of childbearing age. It is characterised by increased intracranial pressure (IP) of unknown aetiology, after ruling out such other entities as brain tumour, hydrocephalus, meningitis, or cerebral venous thrombosis, according to the modified Dandy criteria.1 Initially, such other terms as pseudotumour cerebri or benign intracranial hypertension were used. To avoid ambiguity, some authors advocate naming secondary causes of intracranial hypertension (IH) (eg, steroid withdrawal-related IH) and using the term IIH exclusively to refer to those cases of unknown cause.2 To add to the confusion, the term pseudotumour cerebri syndrome (PTCS) has reappeared in most of the recently published diagnostic criteria.3 This reintroduction is controversial and is not widely accepted by experts in IIH.2

We describe the case of a 27-year-old woman who was admitted to our hospital due to a 2-week history of progressive-onset headache in the occipital region and radiating to the whole head, with 9/10 intensity on the visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain. She also presented intense photophobia, mild phonophobia, dizziness, and pulsatile tinnitus. The patient reported no previous nausea, vomiting, exertion, head trauma, or fever. Twenty-four hours after symptom onset, she experienced a moving spot in the right eye.

History: obesity (1.59m tall and 83kg, BMI: 32.8kg/m2). She had a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD), inserted 2 years earlier, and in the 7 days prior to symptom onset she had received antibiotic treatment with minocycline (100mg twice a day) due to an inguinal folliculitis diagnosed by her family care physician.

Neurological examination: no alterations were identified in the confrontation visual field examination. Isochoric and reactive pupils. Preserved direct photomotor reflex and consensual response. No motor impairment. No cerebellar or meningeal signs.

Ophthalmological examination: scintillating scotoma in the right eye (OD). Visual acuity in the OD: 10/10; left eye (OS): 10/10. Biomicroscopy displayed no alterations. Eye fundus: OD: pronounced papilloedema (stage 4 on the modified Frisén scale) and central, discrete vitreous haemorrhage; OS: less pronounced papilloedema.

The visual field test could not be performed in the emergency department. Chest radiography, brain CT scan, and CT venography showed no alterations.

Minocycline was suspended. Lumbar puncture yielded clear cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with an opening pressure of 25cmH2O; CSF biochemical, cytological, and microbiological studies showed normal results. Twelve hours later, opening pressure was 6cmH2O, with no headache due to analgesic treatment with metamizole 2g, administered 3 times daily and acetazolamide 250mg twice daily. Scotoma resolved at 24hours, with papilloedema improving significantly. The patient started on a diet prescribed by a nutritionist.

Blood count revealed no anaemia or leukocytosis, normal C-reactive protein, and ESR of 43mm/hour. Total cholesterol was 208mg/dL; uric acid, folic acid, vitamin B12, and thyroid function displayed no alterations. Anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-Treponema pallidum, and HIV-1 and 2 yielded negative results.

A brain magnetic resonance imaging scan performed a week later did not reveal signs suggestive of IH.

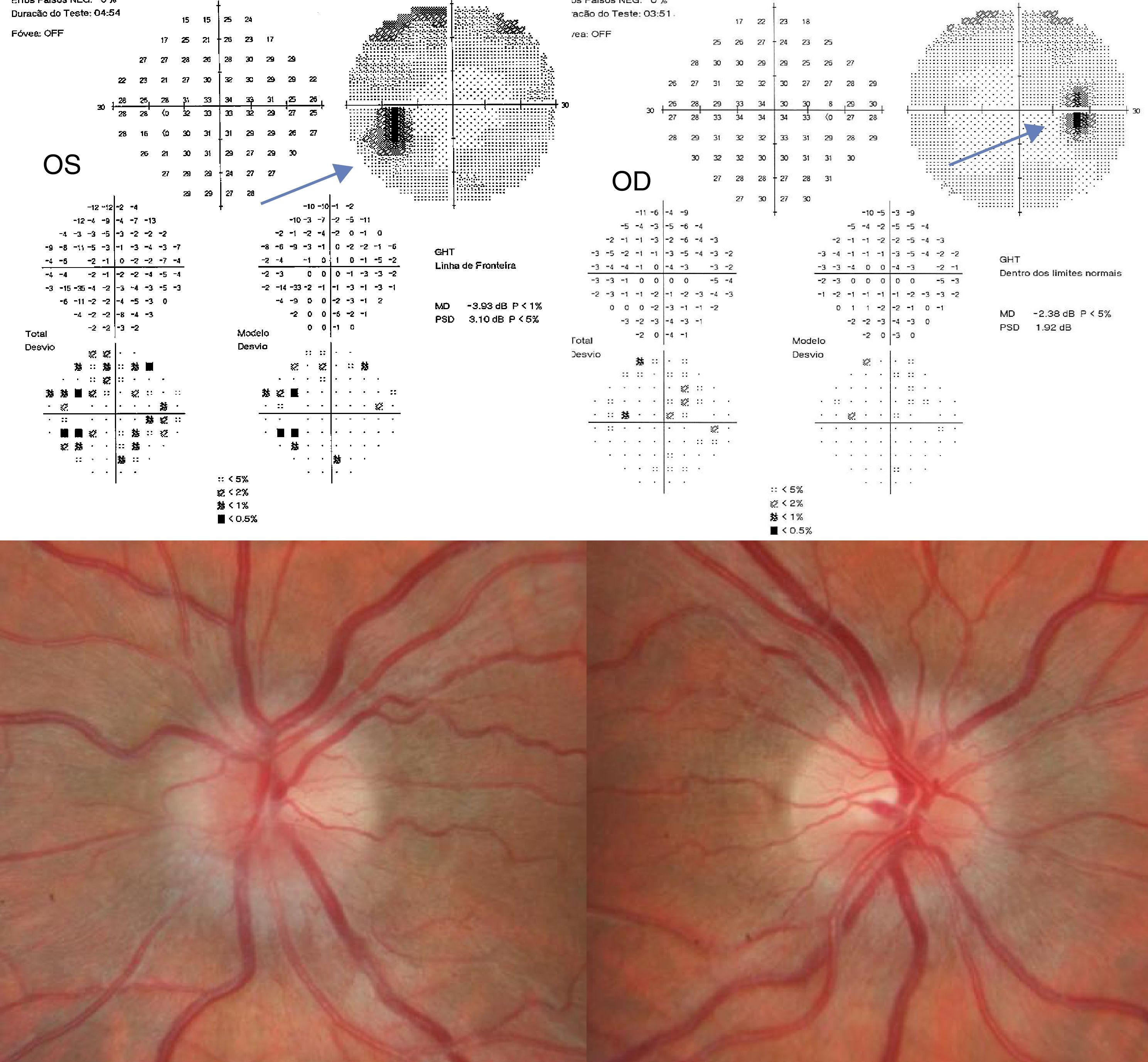

An ophthalmological examination 2 weeks after symptom onset showed improvement of the papilloedema (stage 3 in the OS and stage 2 in the OD) and 30-2 Humphrey visual field test showed a bilateral enlargement of the blind spot, predominantly in the left eye (Fig. 1). As the IUD could potentially contribute to exacerbating or worsening IH, it was removed 3 weeks after symptom onset.

Four weeks after symptom onset, the patient returned to work without analgesia, with a body weight of 79kg.

Our patient meets the modified Dandy criteria for IH (symptoms of IH, increased IP, normal CSF, no brain lesion). Considering the sudden onset of symptoms, the fast, favourable response after suspension of minocycline, and the decrease in IP at 12hours after it increased, we believe this to be a case of minocycline-induced IH with the IUD playing a predisposing role. Weight loss and medical treatment helped resolve symptoms, together with suspension of minocycline and removal of the IUD.

According to the latest diagnostic criteria for IIH, the condition may be diagnosed in the absence of papilloedema if criteria B-E are met and the patient displays sixth nerve palsy. In the absence of papilloedema and sixth cranial nerve palsy, diagnosis of IIH may be suggested but not established in patients meeting criteria B-E as well as at least 3 of the following imaging criteria: empty sella, flattening of the globe, distension of the perioptic subarachnoid space with or without tortuosity of the optic nerve, and stenosis of the transverse venous sinus.3

The literature includes cases of IH induced by use of minocycline in isolation4–7 or combined with vitamin A.8 A retrospective study of 12 patients by Chiu et al.6 reports 2 patients developing the symptoms one year after starting treatment with minocycline.

Regarding the possible association between IUD and IH, one study reports 56 cases of IH or disc oedema in patients with IUDs.9 According to the authors, the devices may contribute to the development or exacerbation of PTCS/IIH.9

Furthermore, there are other reported cases of IH related to IUD use (FDA, 2014; Martínez et al., 2010), including the case of an Argentinian woman without obesity who developed IH 4 years after placement of an IUD. Likewise, the United States Food and Drug Administration's Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) database was found to include a higher than expected number of cases of IH associated with the use of IUD.10

In conclusion, recognising IH trigger factors is essential to early resolution of symptoms. Periodic eye fundus examination of patients receiving minocycline would be advisable, as would informing women regarding the risks of some hormone therapies.

Please cite this article as: Ros Forteza FJ, Pereira Marques I. Hipertensión intracraneal inducida por minociclina en mujer portadora de dispositivo intrauterino de levonorgestrel. Neurología. 2019;34:551–553.