Genetic variance of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a strong determinant of this disorder. The 40bp variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) located in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of DAT1 gene increases the expression of the dopamine transporter. Therefore, DAT1 has been associated with susceptibility to ADHD.

ObjectiveTo determine the association between the VNTR of DAT1 and the phenotype of ADHD or its endophenotypes in a sample of children aged between 6 and 15 years from Bogotá.

Subjects and methodsWe selected 73 patients with ADHD and 54 controls. WISC test was applied in all subjects and executive functions were assessed. The VNTR of DAT1 was amplified by polymerase chain reaction. Data regarding population genetics and statistical analysis were obtained. Correlation and association tests between genotype and neuropsychological testing were performed.

ResultsThe DAT1 polymorphism was not associated with ADHD (P=.85). Nevertheless, the 10/10 genotype was found to be correlated with the processing speed index (P<.05). In the hyperactivity subtype, there was a genotypic correlation with some subtests of executive function (cognitive flexibility) (P≤.01). In the combined subtype, the 10/10 genotype was associated with verbal comprehension index of WISC (P<.05).

ConclusionsA correlation was found between DAT1 VNTR and the subtest “processing speed index” of WISC and the subtest “cognitive flexibility” of executive functions. To our knowledge, this is the first report to assess DAT1 gene in a Colombian population.

La variancia genética del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH) es determinante para el fenotipo. La repetición en tándem en número variable (VNTR) de 40 pares de bases (pb) en la región no traducida 3′ (UTR) del gen DAT1 se ha asociado ala susceptibilidad de presentar TDAH debido al incremento de expresión del transportador de dopamina.

ObjetivoDeterminar la asociación entre el VNTR del DAT1 y el fenotipo y/o endofenotipos del TDAH en una muestra de niños de 6 a 15 años de la ciudad de Bogotá.

Sujetos y métodosSe seleccionó a 73 pacientes con TDAH y 54 controles. En todos los individuos se realizó una prueba de WISC y se valoraron las funciones ejecutivas. Mediante reacción en cadena de la polimerasa se amplificó el VNTR de DAT1. Se establecieron estadísticos genético-poblacionales, análisis de asociación y correlación entre las pruebas neuropsicológicas y el genotipo.

ResultadosEl polimorfismo del DAT1 no mostró asociación con TDAH (p=0,85). Sin embargo, el genotipo 10/10 evidenció asociación con el índice de velocidad de procesamiento (p<0,05). En el subtipo hiperactividad hubo correlación genotípica con subpruebas de la función ejecutiva (flexibilidad cognitiva) (p≤0,01). En el subgrupo mixto, el genotipo 10/10 se asoció al índice de comprensión verbal del WISC (p<0,05).

ConclusionesSe encontró una correlación entre el genotipo del VNTR de DAT1 con la subprueba «índice de velocidad de procesamiento» del WISC y la subprueba «flexibilidad cognitiva» de la función ejecutiva. Este es el primer reporte que evalúa el gen DAT1 en población colombiana con TDAH.

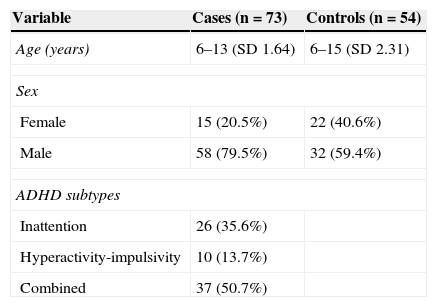

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neuropsychiatric problems in school-aged children. Its worldwide prevalence ranges from 4% to 19%.1,2 This disorder accounts for a sizeable portion of all child psychiatry and neurology consults in specialist centres. It affects boys more than girls by a ratio of 3:1. Furthermore, it has an impact on the individual's academic performance, peer relations, and future life, since some symptoms may remain into adulthood.

Several factors that contribute to the disease's aetiology have been described. Since these factors may be environmental, psychological, and genetic, ADHD is regarded as a multifactorial disease. Its estimated heritability of 76% indicates that genetic variance contributes greatly to development of the phenotype. Several studies have been designed to search for candidate genes.3–5 Genes that may be involved in the disorder have been identified based on the action mechanism of certain drugs used to lessen the symptoms. These genes may act on the pathways related to the dopaminergic, acetylcholinergic, and serotonergic systems on the one hand, or code for transmembrane proteins on the other. Research has shown that genes coding for the dopamine transporter (DAT1), dopamine receptors (DRD2, DRD3, DRD4, and DRD5), the serotonin transporter (5-HTT), serotonin receptors 1B and 2A, the catechol-O-methyltransferase enzyme (COMT), the monoamine oxidase enzyme (MAO), and the protein associated with synaptosome 25 (SNAP25 protein) can be linked to increased susceptibility to the disorder.4 Faraone et al. examined the ORs from several case-control studies and family-based allele transmission studies in their review of the literature on genetics in ADHD. They concluded that variants of the DRD4, DAT1, DRD5, DBH, SNAP-25 and 5-HTT genes were in fact linked to increased susceptibility for developing this disorder.5

One of the best-studied candidate genes is DAT1, which codes for the DAT receptor. This gene began to be studied when researchers observed that many of the drugs used to treat ADHD act by blocking the action of the dopamine transporter. This increases dopamine availability at the synaptic cleft, which in turn contributes to alleviating the symptoms.6–8 Different studies have shown that polymorphisms of the DAT1 gene, such as the variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) of 40bp located in the 3′ UTR, may be regarded as risk factors since they increase expression of the dopamine transporter.9–14 The genotypes for this VNTR are determined by the number of 40-bp repeats in each of an individual's two alleles. The most common types worldwide are the 9-repeat allele (allele 9) and the 10-repeat allele (allele 10). The 10/10 genotype, meaning the genotype with two 10-repeat alleles of 40bp, has been shown to be associated with ADHD. However, this association has not been replicated in all studies analysing this genetic variant. As a result, experts do not yet agree on how much this polymorphism influences susceptibility to the disorder.15–17

In light of the discrepancies between results from studies analysing susceptibility genes, researchers have proposed studying endophenotypes, which may represent changes in biochemical, neurophysiological, or cognitive functions. Indirectly, endophenotypes are a sign of specific pathophysiological processes or subphenotypes of the disease.18 For example, executive function anomalies are common in ADHD patients, and they may be regarded as an endophenotype of the disorder.19 On this basis, we may conclude that studying these anomalies may help identify genetic variants related specifically to the changes in executive functions that are typical in ADHD.

To date, no Colombian studies have examined the association between the DAT1 gene and ADHD endophenotypes. The purpose of our study was therefore to determine if there is an association between the 40-bp VNTR in the 3′ UTR region of DAT1 and the ADHD phenotype, subtypes, and endophenotypes (mainly executive function), in a Colombian population sample.

Subjects and methodsSubjectsWe selected children aged 6 to 15 from various public and private schools in Bogotá, Colombia. Subjects were evaluated using the DSM-IV checklist for ADHD, the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC), and the revised Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-R). Cases were selected according to results on the DSM-IV checklist and the BASC scale. Children who met 6 or more of the 9 criteria for inattention and/or hyperactivity on the DSM-IV checklist and who tested at or below the 85th percentile in the attention problems and hyperactivity domain of the BASC scale, according to teacher and parent ratings, were considered cases. The WISC-R test was applied to exclude children with intellectual disability, defined as a total score of less than 70. Cases were classified as hyperactive/impulsive, inattentive, or combined ADHD subtypes based on test results.

A control group of children not suspected of having ADHD was formed; these children were also assessed with the DSM-IV checklist and BASC scale. Controls were also screened for cognitive disability; we excluded individuals with scores lower than 70 on the WISC-R, and those with poor academic performance (in cases in which the test could not be administered for operational reasons). Executive functions in both cases and controls were examined using ENI (Evaluación Neuropsicológica Infantil), a Spanish-language neuropsychological assessment for children.20

This study complies with ethical principles for medical research on human subjects as set forth by the Helsinki Declaration and the World Medical Association (Seoul, 2008) and Resolution 008430 of 1993, establishing the scientific, technical, and administrative guidelines for medical research in Colombia. The study protocol was assessed and approved by our hospital's research ethics committee. All participating children (cases and controls) agreed to participate in the study; parents signed informed consent forms permitting them to participate and authorising researchers to use the children's DNA samples.

DNA extractionIn cases and controls, we collected 5mL of peripheral venous blood or buccal swab samples, depending on how difficult it was to draw blood samples from these children. DNA extraction was performed using a conventional desalting protocol; molecule quality was assessed in 1.2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. DNA was quantified using a Nanodrop® spectrophotometer. Prior to being used, DNA from cases and controls was stored at –20°C at the DNA bank maintained by the genetics unit at Universidad del Rosario (Bogotá, Colombia).

GenotypingThe 40-bp VNTR polymorphism in the 3′ UTR end of the DAT1 gene was analysed using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method and previously described specific primers9 that amplified a fragment measuring between 160 and 640bp, according to the number of VNTRs present in each case or control. The smaller allele (2 repeats) corresponded to a molecular weight of 160bp, whereas the larger allele (13 repeats) had a molecular weight of 640bp.

PCR was performed under the following conditions: Master Mix (6.25μL Promega®), forward primer 0.5μL and reverse primer 0.5μL (10 PM/μL), DNA 150ng, ultrapure water 5.25μL, and 2μL dimethyl sulfoxide at 10%. The thermal cycler programme was as follows: denaturing at 94°C during 5min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 45s, annealing at 61°C for 45s, and extension at 72°C for 45s, with a final extension cycle of 10min at 72°C (Agilent® thermal cycler). Each PCR setup included a negative control for non-specific amplification so as to discard any contaminated samples. As positive controls, we used samples that had previously been genotyped in the 3′ UTR region of DAT1. All amplified products were analysed in 3% agarose gels stained with 3% ethidium bromide, using a 50bp molecular weight size marker. Two co-researchers, working independently, performed genotyping by viewing the amplified product in gel, and they calculated allele frequencies by direct counting. The genotype was assigned by comparing results to the amplified band profile obtained using the molecular weight pattern, keeping in mind that the allele with fewer repetitions (2) had a weight of 160bp.

Statistical analysisSNPStats software21 was used to determine population-wide genetic statistics for allele frequency, genotype frequency, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. We calculated the ORs for genotype vs phenotype and ADHD subtypes. SPSS software version 20 was used to perform bivariate analyses using tests for correlation between the VNTR genotype at the 3′ UTR end of the DAT1 gene and results on the WISC subtests, ENI executive function subtests (fluency, writing fluency, cognitive flexibility, planning, and organisation), and the ENI memory and human figure drawing tests. Results were evaluated with an error rate of 5% (P<.05).

ResultsWe analysed 73 children diagnosed with ADHD aged between 6 and 13 years (SD 1.64) and 54 healthy controls aged between 6 and 15 years (SD 2.31). Cases were classified in three different subtypes according to results on the DSM-IV ADHD classification and the BASC scale. Most cases were matched to the combined subtype. The male to female ratio in the case group was approximately 4:1 (Table 1).

Due to low concentrations of available DNA, genotyping could not be performed on four of the extracted samples, which corresponded to a single control and three cases. Of the latter, two were classified as inattentive and the third as hyperactive.

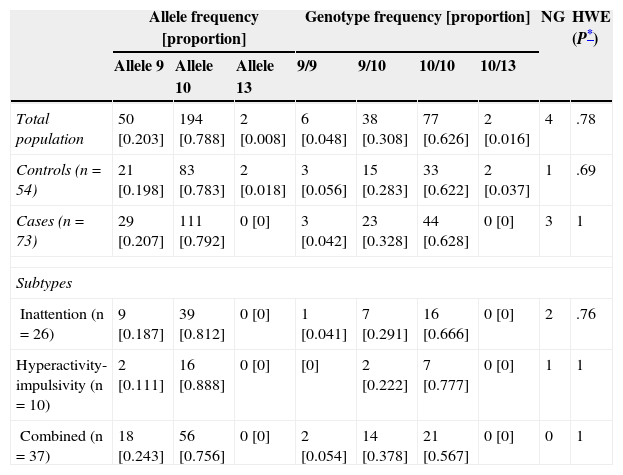

There were no significant differences in allele and genotype frequencies between cases and controls (P=.26 and P=.39, respectively; Table 2). The population was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P=.78). The most frequent genotype in both cases and controls was 10/10 (two 10-repeat alleles); frequencies were 62.8% and 62.2%, respectively.

Values observed and percentage of allele and genotype frequencies of cases and controls

| Allele frequency [proportion] | Genotype frequency [proportion] | NG | HWE (P*) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele 9 | Allele 10 | Allele 13 | 9/9 | 9/10 | 10/10 | 10/13 | |||

| Total population | 50 [0.203] | 194 [0.788] | 2 [0.008] | 6 [0.048] | 38 [0.308] | 77 [0.626] | 2 [0.016] | 4 | .78 |

| Controls (n=54) | 21 [0.198] | 83 [0.783] | 2 [0.018] | 3 [0.056] | 15 [0.283] | 33 [0.622] | 2 [0.037] | 1 | .69 |

| Cases (n=73) | 29 [0.207] | 111 [0.792] | 0 [0] | 3 [0.042] | 23 [0.328] | 44 [0.628] | 0 [0] | 3 | 1 |

| Subtypes | |||||||||

| Inattention (n=26) | 9 [0.187] | 39 [0.812] | 0 [0] | 1 [0.041] | 7 [0.291] | 16 [0.666] | 0 [0] | 2 | .76 |

| Hyperactivity-impulsivity (n=10) | 2 [0.111] | 16 [0.888] | 0 [0] | [0] | 2 [0.222] | 7 [0.777] | 0 [0] | 1 | 1 |

| Combined (n=37) | 18 [0.243] | 56 [0.756] | 0 [0] | 2 [0.054] | 14 [0.378] | 21 [0.567] | 0 [0] | 0 | 1 |

HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; NG: no genotyping.

We did not observe an association between the genotype of the VNTR in the 3′ UTR of DAT1 and the ADHD phenotype (P=.85). Neither were there any associations between genotype and the inattentive, hyperactive/impulsive, and combined subtypes (P=.83, P=.40, and P=.44, respectively).

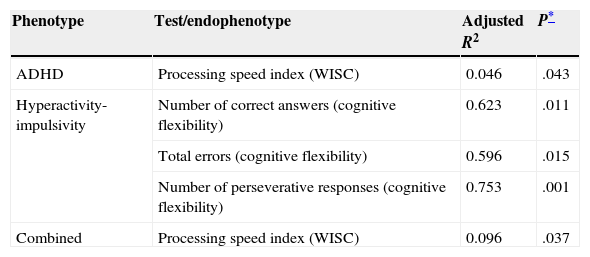

A correlation study for the VNTR genotype in 3′ UTR of DAT1 and the subtests from both the WISC and the executive functions domain of the ENI revealed a statistically significant correlation only between genotype and the processing speed index (PSI) on WISC (P=.043, Table 3). We determined that cases with the 10/10 genotype had lower mean scores on this index than subjects with other genotypes (mean with 10/10 genotype=88; mean with 9/9 or 9/10 genotype=95).

Statistically significant correlations between endophenotypes and VNTR genotype at the 3′ UTR section of DAT1

| Phenotype | Test/endophenotype | Adjusted R2 | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | Processing speed index (WISC) | 0.046 | .043 |

| Hyperactivity-impulsivity | Number of correct answers (cognitive flexibility) | 0.623 | .011 |

| Total errors (cognitive flexibility) | 0.596 | .015 | |

| Number of perseverative responses (cognitive flexibility) | 0.753 | .001 | |

| Combined | Processing speed index (WISC) | 0.096 | .037 |

The inattention subtype did not show any correlations between genotype and the subtests that were analysed. However, some subtests such as total phonemic word fluency and semantic graphic fluency yielded P-values approaching statistical significance (P=.062 and P=.084, respectively). For the hyperactive/impulsive subtype, the DAT1 genotype was associated with the number of correct responses (P=.011) and errors (P=.015) on the cognitive flexibility subtest, as well as with the number of perseverative answers (P=.001). For the combined subtype, only the WISC verbal comprehension index results showed a significant association with genotype (P=.037).

In addition, we performed an analysis broken down by genotype subgroups to assess the influence of alleles on endophenotypes. This entailed creating a group for genotypes containing the 9-repeat allele (i.e. genotypes 9/9 and 9/10) and another for those lacking the 9-repeat allele (genotypes 10/10 and 10/13). Through this analysis, we detected a group effect on the PSI subtest from the WISC (P=.033); the mean score was higher on this index for cases bearing the 9-repeat allele (94 vs 88). No other correlations were identified.

DiscussionThe dopamine transporter, which is located in the presynaptic region in dopaminergic neurons, regulates dopamine reuptake by presynaptic terminals.22DAT1, the gene that codes for this protein, has been examined by numerous association studies in ADHD since it displays multiple features that make it a good candidate gene. Knock-out mice exhibit increased motor activity with dopamine remaining in the synaptic cleft 100 times longer than in normal mice.8 SPECT and PET studies of patients with the disorder reveal higher striatal densities of DAT1.23 This gene product is the target of the drug methylphenidate, whose action mechanism blocks more than 50% of dopamine transporters at the presynaptic neuron level.6,24

Findings from our study indicate that the 10/10 genotype in patients with ADHD was associated with scores on the processing speed index. This is a test of the subject's ability to focus attention and scan quickly, and it provides information about attention span and short-term visual memory. Mean processing speed index scores were lower among carriers of this genotype, indicating that these individuals show alterations in this area. Likewise, allele-specific analysis confirmed the correlation between individuals homozygous for the 10-repeat allele and the processing speed index. This finding indicates that this allele is responsible for susceptibility to an altered endophenotype; similarly, findings from the study by Bellgrove et al. show that the 10-repeat allele may contribute to the appearance of a neuropsychological variant.25

Likewise, the analysis by ADHD subtype showed that the 10/10 genotype in hyperactive/impulsive individuals was linked to a lower number of correct responses, the total number of errors on the card sorting test, and the number of perseverative answers. Viewed as a whole, these tests provide information about individuals’ ability to anticipate and establish goals, self-regulate during tasks, and carry out tasks efficiently. They also inform us about a subject's ability to adapt to the requirements in his or her setting. Alterations in these endophenotypes may be linked to this subtype's propensity for poor adaptation to classrooms and other similar settings that change and require individuals to complete tasks in an effective manner.

On the other hand, analysis of the combined subtype found that individuals with the 10/10 genotype presented lower verbal comprehension indexes than did other genotypes. This indicates that the 10/10 genotype is associated with altered verbal ability in children with the combined ADHD subtype. Capilla et al. reported that this subtype presents alterations in cognitive flexibility according to magnetoencephalography (MEG) assessments carried out while subjects were performing tasks involving this function.26

Similarly, other groups have found associations between the 10/10 genotype of this polymorphism and abnormal results on neuropsychological tests. Loo et al. reported a link between the 10/10 genotype of the DAT1 gene and an increase in the total number of errors, in addition to a higher number of impulsive answers and more variability in response time.27 In a case-control study, Bellgrove found a link between this genotype and poor performance on attention-related tasks. This study showed that individuals homozygous for allele 10 showed greater response variability on the test of spatial attentional bias; the researchers indicate that the 10-repeat allele of DAT1 may mediate neuropsychological impairment in ADHD.25 Viewed together, these studies show this polymorphism's key role in executive function alterations caused by ADHD. They also highlight the importance of understanding the genetic substrate of this disorder, and although this is not possible for the disorder with all of its traits, we see that certain neuropsychological anomalies (endophenotypes) may arise in these patients.

As our results show, and as we stated previously, there is an association between ADHD endophenotypes and the 10/10 genotype of the VNTR of DAT1. However, other alleles associated with ADHD have been described in the same VNTR locus, including 7-repeat and 9-repeat alleles. Barkley et al. identified more marked expression of ADHD symptoms in carriers of the 9/10 genotype than in carriers of the 10/10 genotype.28 In addition, this study showed that carriers of the 9/10 genotype display poorer academic performance, more strained mother-child relationships, and more significant behaviour disorders. Kim et al. also found the 9/10 genotype to be more frequent in subjects with ADHD and that frequencies for the 9-repeat allele were significantly higher among subjects with ADHD.29 These authors report that carriers of the 9-repeat allele made more errors of omission on continuous vigilance tasks. Oh et al. found that subjects with the 10/10 genotype made fewer errors of omission on the attention variables test than individuals with genotype 10/* in the first quarter of the test. This indicates the presence of a protective factor for individuals with the 10/10 genotype.30

There may be several explanations for the reports that associate genotypes other than 10/10 with ADHD in different populations. These include inter-population differences in the heritability value; the impact of the psychosocial environment, which is a significant risk factor; and statistical independence for the alleles of the analysed VNTR and other polymorphisms that are functionally responsible for the phenotype. An additional explanation is that haplotypes affect susceptibility to the phenotype more than single polymorphisms. The type of analysis also influences results since population stratification may be present in case-control studies, and patients’ phenotypes and the homozygosity status of the parents may affect analyses of the transmission-disequilibrium test. Numerous studies have failed to identify an association between ADHT and DAT1, although this gene is an optimal biological and physiological candidate. It is therefore believed that the gene may act more like a phenotype modulator whose action depends on interactions with other polymorphisms of dopaminergic pathways, such as DRD4.15,17

Findings from this study underscore the importance of knowing the genotype of the VNTR located at region 3′ UTR of DAT1 in Colombian populations, given that carrying the 10/10 genotype has been linked to poorer performance on neuropsychological tests.

The present study's limitations include its small sample size, which affects the external validity and ability to generalise results. Since the population examined in this study was sampled from a few schools in the city of Bogotá, these results may only be extrapolated to other populations with caution. For future studies, we recommend increasing the sample size on both the local and regional levels, especially in regions where a higher prevalence of the disorder is reported. This will be helpful for identifying low-frequency alleles, which are difficult to detect in small populations.2 We also recommend evaluating more variants of the DAT1 gene and any others that might be masking the relationships reported by earlier studies, and lastly, completing functional studies to shed light on the biological role of this polymorphism in poor performance on the neuropsychological tests listed here.

FundingThis project was funded by the Universidad del Rosario’s research fund (FIUR, Fondo de Investigaciones de la Universidad del Rosario).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank the academic institutions that participated in this project, and the Colsubsidio network of schools, for their contributions and commitment to the study.

Please cite this article as: Agudelo JA, Gálvez JM, Fonseca DJ, Mateus HE, Talero-Gutiérrez C, Velez-Van-Meerbeke A. Evidencia de asociación entre el genotipo 10/10 de DAT1 y endofenotipos del trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad. Neurología. 2015;30:137–143.

This study has not been presented at the SEN Annual Meeting or at any other conferences or congresses.