The objective of the EPICON Project is to develop a set of recommendations on how to adequately switch from carbamazepine (CBZ) and oxcarbazepine (OXC) to eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL) in some patients with epilepsy.

MethodsA steering committee drafted a questionnaire of 56 questions regarding the transition from CBZ or OXC to ESL in clinical practice (methodology and change situation). The questionnaire was then distributed to 54 epilepsy experts in 2 rounds using the Delphi method. An agreement/disagreement consensus was defined when a median ≥7 points or ≤3 was achieved, respectively, and a relative interquartile range ≤0.40. We analysed the results obtained to reach our conclusions.

ResultsOur main recommendations were the following: switching from CBZ to ESL must be carried out over a period of 1 to 3 weeks with a CBZ:ESL dose ratio of 1:1.3 and is recommended for patients who frequently forget to take their medication, those who work rotating shifts, polymedicated patients, subjects with cognitive problems, severe osteoporosis–osteopaenia, dyslipidaemia, or liver disease other than acute liver failure, as well as for men with erectile dysfunction caused by CBZ. The transition from OXC to ESL can take place overnight with an OXC:ESL dose ratio of 1:1 and it is recommended for patients who frequently forget to take their medication, those who work rotating shifts, polymedicated patients, or those with cognitive problems. The transition was not recommended for patients with prior rash due to CBZ or OXC use.

ConclusionThe EPICON Project offers a set of recommendations about the clinical management of switching from CBZ or OXC to ESL, using the Delphi method.

El objetivo del proyecto EPICON es desarrollar una serie de recomendaciones sobre la forma adecuada de realizar el cambio de carbamazepina (CBZ) y oxcarbazepina (OXC) a acetato de eslicarbazepina (ESL) en determinados pacientes con epilepsia.

MétodosUn comité coordinador preparó un cuestionario con 56 preguntas en relación con el cambio de CBZ u OXC a ESL en la práctica clínica (metodología y situaciones del cambio). Posteriormente, se consultó a 54 expertos en epilepsia con el empleo de metodología Delphi (2 rondas de consulta). Se definió un consenso en acuerdo o desacuerdo si las respuestas para el ítem estudiado alcanzaban una mediana ≥ 7 o ≤ 3, respectivamente, y un rango intercuartílico relativo ≤ 0,40. Se analizaron los resultados y se formularon las conclusiones.

ResultadosLas recomendaciones fundamentales fueron: el cambio de CBZ a ESL debe ser realizado en 1-3 semanas, con una equivalencia de dosis CBZ:ESL de 1:1.3, siendo recomendado en pacientes con olvidos de medicación, trabajos por turnos, polimedicados, problemas cognitivos, osteoporosis-osteopenia severa, dislipidemia o enfermedad hepática (ausencia de fallo hepático grave), así como en varones con disfunción eréctil causada por CBZ. El cambio de OXC a ESL puede realizarse de un día para otro con una equivalencia de dosis 1:1 y es recomendado en pacientes con olvidos de medicación, trabajos por turnos, polimedicados o problemas cognitivos. Se desaconsejó el cambio en caso de rash con CBZ u OXC.

ConclusiónEl proyecto EPICON proporciona algunas recomendaciones sobre el manejo clínico del cambio de CBZ u OXC a ESL, mediante el empleo de la metodología Delphi.

The main goal of antiepileptic treatment is to achieve seizure control while keeping adverse effects to a minimum.1 Patient characteristics and comorbidities are important factors to consider when selecting the most appropriate antiepileptic treatment. However, no studies with level 1 evidence have addressed how these factors might recommend certain antiepileptic drugs (AED), which makes this task even more complex.2 Other important aspects to consider are drug–drug interactions3 and the number of daily doses, both of which may affect treatment adherence and increase costs in cases of poor compliance.4,5

These unanswered questions about antiepileptic treatment may explain why new antiepileptic drugs have been marketed in recent years, sometimes resulting in the development of different drugs belonging to the same family. This provides clinicians with more options when it comes to selecting the right drug for each situation. Since there are no studies with a high level of evidence to support the use of specific drugs, consensus statements or treatment recommendations based on expert opinion are the most frequently used sources of evidence in clinical practice. Although these documents have a low level of evidence, they are useful in choosing the most appropriate treatment and may serve as a guide for less experienced clinicians.6–8

Eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL) is a third-generation AED approved by the European Medicines Agency in 2009 and by the Food and Drug Administration in 2013. It has been marketed in Spain since February 2011. ESL is currently indicated as an adjunctive therapy for adults with partial seizures with or without secondary generalisation based on the results of 4 phase-3 randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trials.9–13 These clinical trials found ESL dosed at 800 to 1200mg/day in a single dose to have optimal efficacy and tolerability.

ESL belongs to the dibenzazepine family, as do carbamazepine (CBZ) and oxcarbazepine (OXC), but it differs from the latter 2 drugs at the 10,11 position. These drugs also display differences in metabolism: CBZ is metabolised to carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide whereas OXC and ESL are metabolised to S-licarbazepine, although in different proportions (78.1% vs 93.9%).14,15 The number of daily doses of each drug also differs: single doses in the case of ESL and extended-release OXC (not available in Spain), 2 doses of immediate-release OXC and extended-release CBZ (not available in Spain), and 2 to 3 doses of immediate-release CBZ. According to Soares-da-Silva et al., the action mechanism of ESL has some distinctive features compared to that of other drugs in the same family: 1) the selectivity of interaction with the inactive state of the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC), 2) reduction in VGSC availability through enhancement of slow inactivation, instead of alteration of fast inactivation of VGSC, and 3) inhibition of high- and low-affinity hCaV3.2 inward currents with greater affinity than CBZ.16 These differences in the profiles of AEDs in the dibenzazepine family may result in different levels of effectiveness, tolerability, and adherence,17 which leads doctors to consider switching one drug for another in the same family to adapt treatment to each patient's characteristics. However, very few studies have evaluated treatment recommendations and the specific situations that should be considered before switching drugs in certain patients.18–21

The EPICON project, in which a panel of experts in epilepsy have adopted the Delphi method, evaluated certain situations and the methodology for switching from CBZ or OXC to ESL. The purpose of our study was to issue consensus recommendations for switching from CBZ or OXC to ESL in certain patients. These recommendations may help less experienced specialists make better decisions in clinical practice.

Material and methodsDelphi methodThe Delphi method is a research technique for consensus building. It draws from qualitative information in the form of opinions from multiple experts, based on their knowledge, experience, and cumulative data. This method constitutes a complementary or alternative source of information (the only source of data in some cases), and it aims to lessen the level of uncertainty and help with decision making.22

The Delphi method, used to facilitate consensus among a group of experts, has the following features: 1) interactive process in which a panel of experts answers a series of questions at least twice (these experts are likely to reach a consensus in the second round, at which time they already know the opinion of the rest of the group and may therefore change or maintain their first-round responses); 2) expert opinions are anonymous; 3) data are managed by a coordination committee; and 4) the method is qualitative. Although such concepts as sampling errors and statistical significance are not relevant, the Delphi method relies on the participation of a select number of experts with abundant knowledge of and experience with the topic. Questions are worded in such a way that the opinions expressed in response to them can be treated as quantitative data. In this way, all indicators and measures obtained will facilitate both information-sharing and decision-making, according to the degree of consensus that is reached per question.

Study designWe created a coordination committee comprising 8 specialists in epilepsy (HB, JO, JP, RAR, JJRU, PJSC, VV, and CV). These experts designed and coordinated the EPICON project and analysed the results. We subsequently established a panel of 54 specialists in epilepsy from different regions in Spain. Experts were selected by the coordination committee based on their experience in managing epilepsy. All were neurologists specialising in epilepsy and working at epilepsy specialist clinics or epilepsy units that together represented all of Spain's geographical areas. All experts agreed to participate in the project.

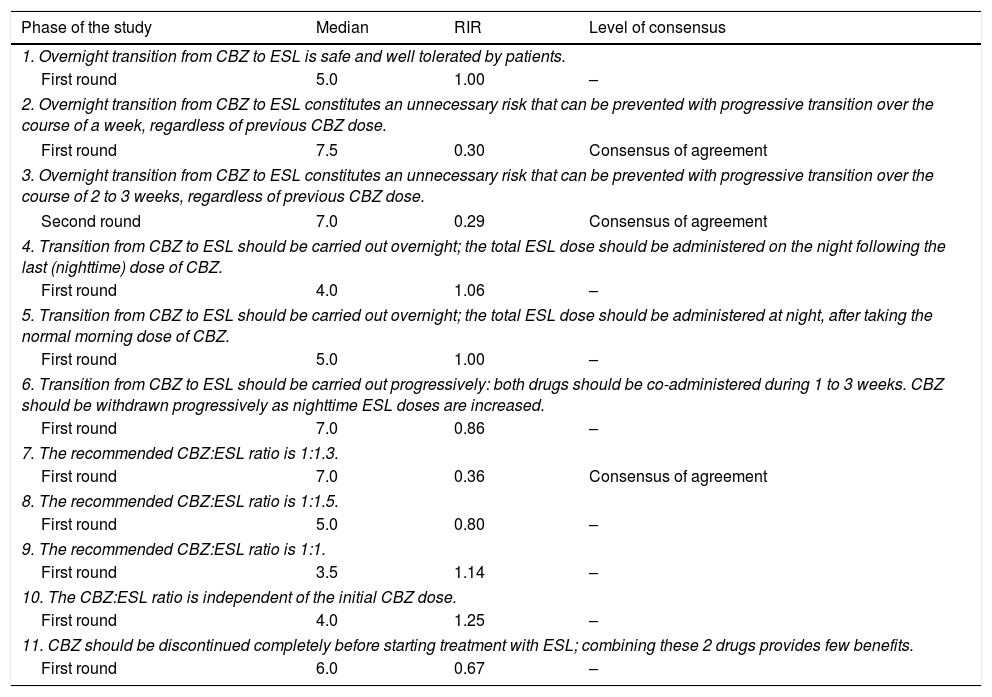

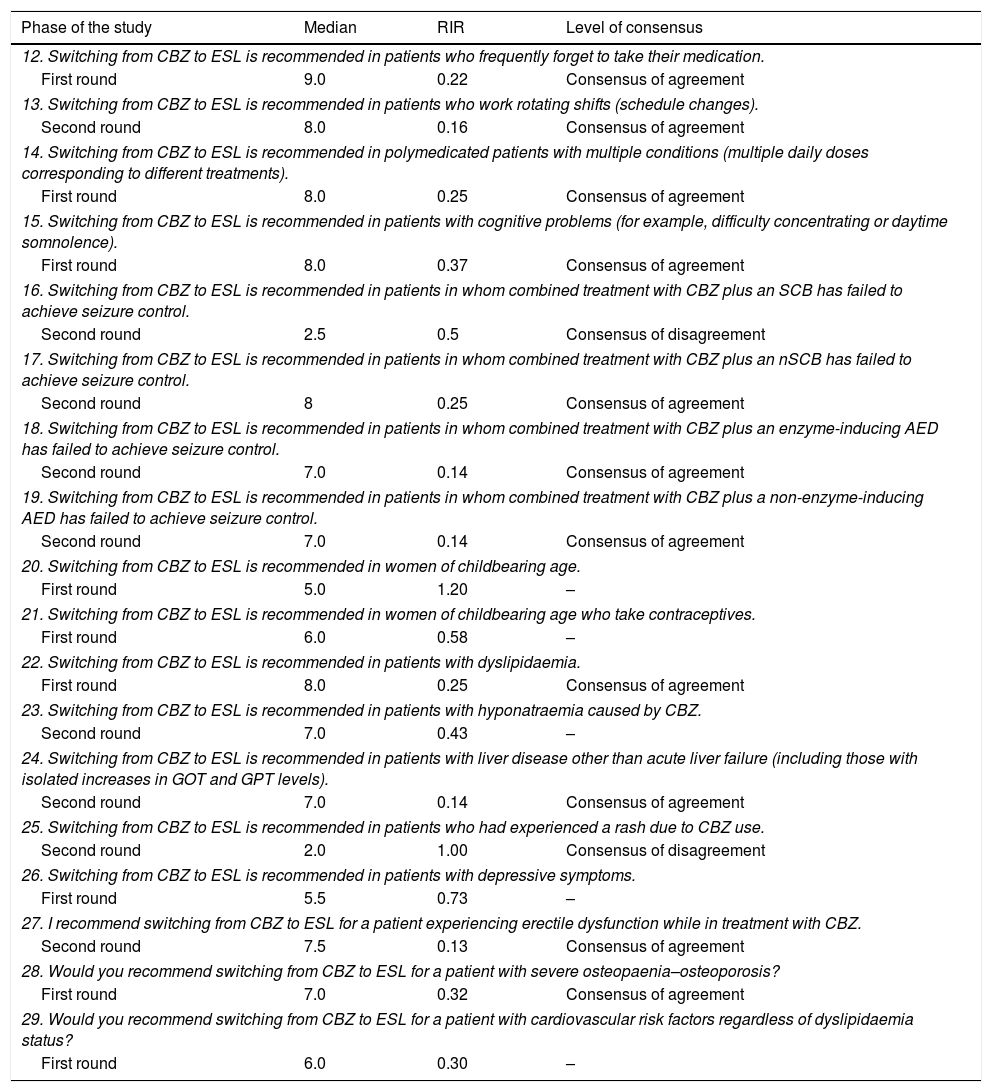

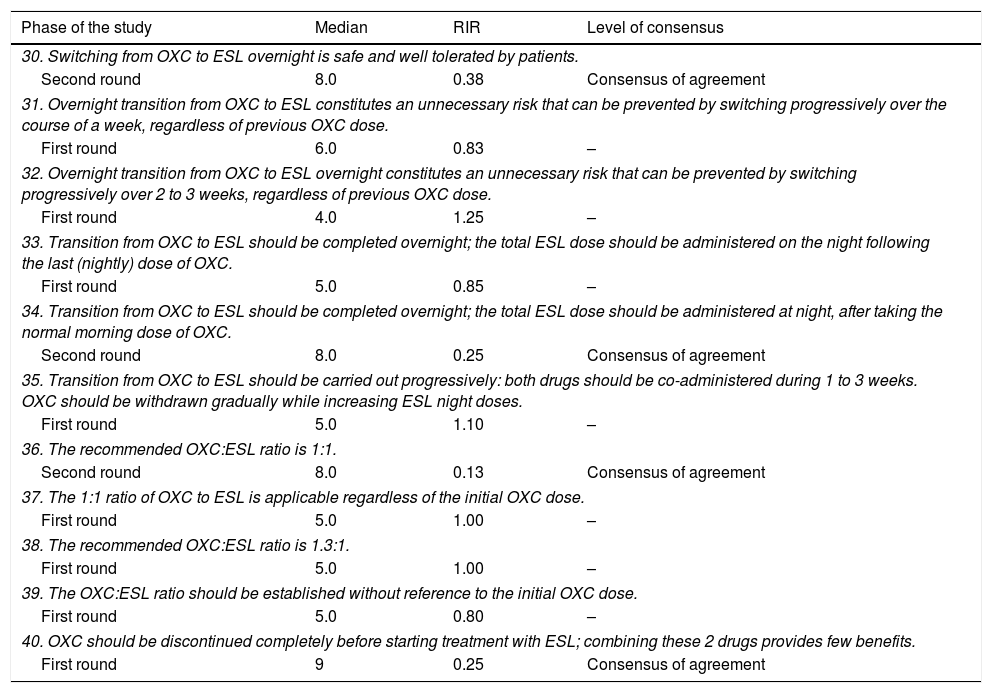

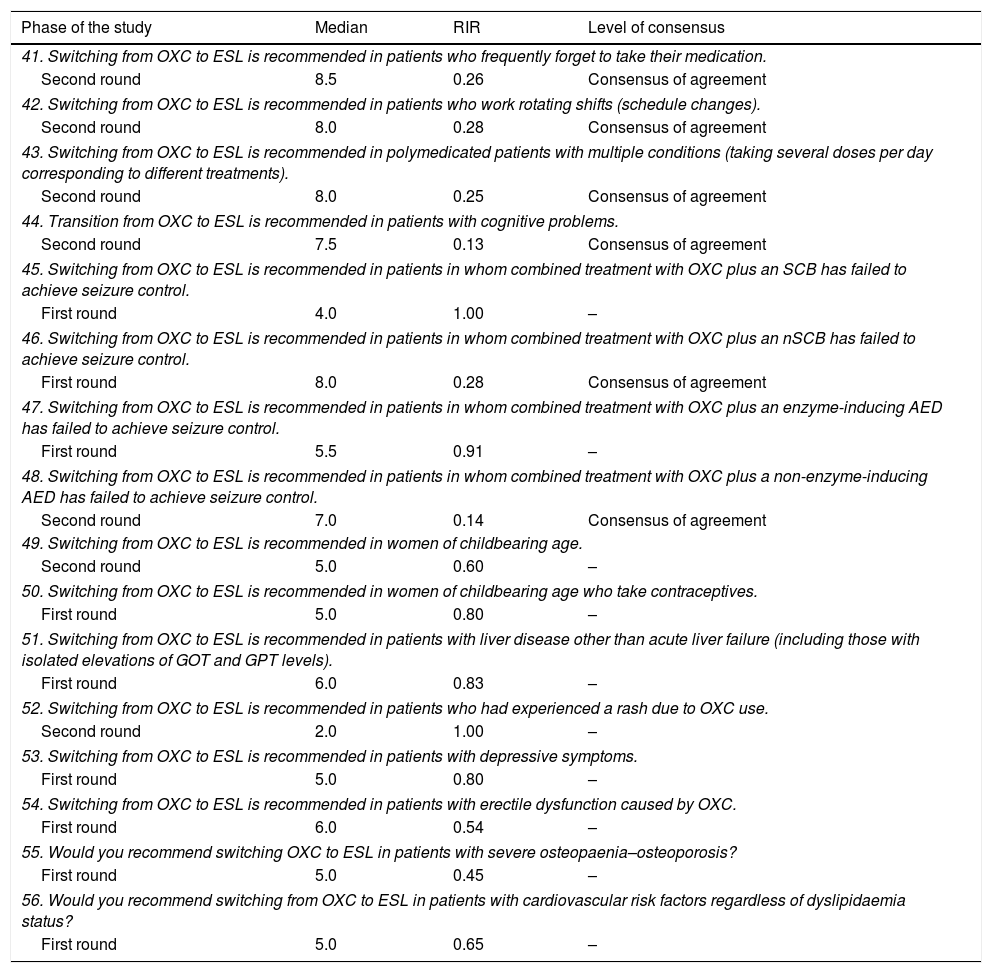

The members of the panel were subsequently asked a series of questions following the Delphi method. The coordination committee designed a questionnaire including 56 questions (Tables 1A–1D) distributed in 4 sections and addressing different situations affecting drug switching from CBZ or OXC to ESL: section ‘Carbamazepine: methodology for switching’ (items 1-11; Table 1A), section ‘Carbamazepine: situations favourable to switching’ (items 12-29; Table 1B), section ‘Oxcarbazepine: methodology for switching’ (items 30-40; Table 1C), and section ‘Oxcarbazepine: situations favourable to switching’ (items 41-56; Table 1D). The coordinators shared their ideas and suggestions for items to be included in the study, which served as the basis for creating the questionnaire. The studies used for drafting the questions were listed at the end of the questionnaire.

Questions and results from the section ‘Carbamazepine: methodology for switching’.

| Phase of the study | Median | RIR | Level of consensus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Overnight transition from CBZ to ESL is safe and well tolerated by patients. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 1.00 | – |

| 2. Overnight transition from CBZ to ESL constitutes an unnecessary risk that can be prevented with progressive transition over the course of a week, regardless of previous CBZ dose. | |||

| First round | 7.5 | 0.30 | Consensus of agreement |

| 3. Overnight transition from CBZ to ESL constitutes an unnecessary risk that can be prevented with progressive transition over the course of 2 to 3 weeks, regardless of previous CBZ dose. | |||

| Second round | 7.0 | 0.29 | Consensus of agreement |

| 4. Transition from CBZ to ESL should be carried out overnight; the total ESL dose should be administered on the night following the last (nighttime) dose of CBZ. | |||

| First round | 4.0 | 1.06 | – |

| 5. Transition from CBZ to ESL should be carried out overnight; the total ESL dose should be administered at night, after taking the normal morning dose of CBZ. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 1.00 | – |

| 6. Transition from CBZ to ESL should be carried out progressively: both drugs should be co-administered during 1 to 3 weeks. CBZ should be withdrawn progressively as nighttime ESL doses are increased. | |||

| First round | 7.0 | 0.86 | – |

| 7. The recommended CBZ:ESL ratio is 1:1.3. | |||

| First round | 7.0 | 0.36 | Consensus of agreement |

| 8. The recommended CBZ:ESL ratio is 1:1.5. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 0.80 | – |

| 9. The recommended CBZ:ESL ratio is 1:1. | |||

| First round | 3.5 | 1.14 | – |

| 10. The CBZ:ESL ratio is independent of the initial CBZ dose. | |||

| First round | 4.0 | 1.25 | – |

| 11. CBZ should be discontinued completely before starting treatment with ESL; combining these 2 drugs provides few benefits. | |||

| First round | 6.0 | 0.67 | – |

RIR: relative interquartile range.

Questions and results from the section ‘Carbamazepine: situations favourable to switching’.

| Phase of the study | Median | RIR | Level of consensus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients who frequently forget to take their medication. | |||

| First round | 9.0 | 0.22 | Consensus of agreement |

| 13. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients who work rotating shifts (schedule changes). | |||

| Second round | 8.0 | 0.16 | Consensus of agreement |

| 14. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in polymedicated patients with multiple conditions (multiple daily doses corresponding to different treatments). | |||

| First round | 8.0 | 0.25 | Consensus of agreement |

| 15. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients with cognitive problems (for example, difficulty concentrating or daytime somnolence). | |||

| First round | 8.0 | 0.37 | Consensus of agreement |

| 16. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients in whom combined treatment with CBZ plus an SCB has failed to achieve seizure control. | |||

| Second round | 2.5 | 0.5 | Consensus of disagreement |

| 17. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients in whom combined treatment with CBZ plus an nSCB has failed to achieve seizure control. | |||

| Second round | 8 | 0.25 | Consensus of agreement |

| 18. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients in whom combined treatment with CBZ plus an enzyme-inducing AED has failed to achieve seizure control. | |||

| Second round | 7.0 | 0.14 | Consensus of agreement |

| 19. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients in whom combined treatment with CBZ plus a non-enzyme-inducing AED has failed to achieve seizure control. | |||

| Second round | 7.0 | 0.14 | Consensus of agreement |

| 20. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in women of childbearing age. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 1.20 | – |

| 21. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in women of childbearing age who take contraceptives. | |||

| First round | 6.0 | 0.58 | – |

| 22. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients with dyslipidaemia. | |||

| First round | 8.0 | 0.25 | Consensus of agreement |

| 23. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients with hyponatraemia caused by CBZ. | |||

| Second round | 7.0 | 0.43 | – |

| 24. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients with liver disease other than acute liver failure (including those with isolated increases in GOT and GPT levels). | |||

| Second round | 7.0 | 0.14 | Consensus of agreement |

| 25. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients who had experienced a rash due to CBZ use. | |||

| Second round | 2.0 | 1.00 | Consensus of disagreement |

| 26. Switching from CBZ to ESL is recommended in patients with depressive symptoms. | |||

| First round | 5.5 | 0.73 | – |

| 27. I recommend switching from CBZ to ESL for a patient experiencing erectile dysfunction while in treatment with CBZ. | |||

| Second round | 7.5 | 0.13 | Consensus of agreement |

| 28. Would you recommend switching from CBZ to ESL for a patient with severe osteopaenia–osteoporosis? | |||

| First round | 7.0 | 0.32 | Consensus of agreement |

| 29. Would you recommend switching from CBZ to ESL for a patient with cardiovascular risk factors regardless of dyslipidaemia status? | |||

| First round | 6.0 | 0.30 | – |

RIR: relative interquartile range.

Questions and results from the section ‘Oxcarbazepine: situations favourable to switching’.

| Phase of the study | Median | RIR | Level of consensus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30. Switching from OXC to ESL overnight is safe and well tolerated by patients. | |||

| Second round | 8.0 | 0.38 | Consensus of agreement |

| 31. Overnight transition from OXC to ESL constitutes an unnecessary risk that can be prevented by switching progressively over the course of a week, regardless of previous OXC dose. | |||

| First round | 6.0 | 0.83 | – |

| 32. Overnight transition from OXC to ESL overnight constitutes an unnecessary risk that can be prevented by switching progressively over 2 to 3 weeks, regardless of previous OXC dose. | |||

| First round | 4.0 | 1.25 | – |

| 33. Transition from OXC to ESL should be completed overnight; the total ESL dose should be administered on the night following the last (nightly) dose of OXC. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 0.85 | – |

| 34. Transition from OXC to ESL should be completed overnight; the total ESL dose should be administered at night, after taking the normal morning dose of OXC. | |||

| Second round | 8.0 | 0.25 | Consensus of agreement |

| 35. Transition from OXC to ESL should be carried out progressively: both drugs should be co-administered during 1 to 3 weeks. OXC should be withdrawn gradually while increasing ESL night doses. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 1.10 | – |

| 36. The recommended OXC:ESL ratio is 1:1. | |||

| Second round | 8.0 | 0.13 | Consensus of agreement |

| 37. The 1:1 ratio of OXC to ESL is applicable regardless of the initial OXC dose. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 1.00 | – |

| 38. The recommended OXC:ESL ratio is 1.3:1. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 1.00 | – |

| 39. The OXC:ESL ratio should be established without reference to the initial OXC dose. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 0.80 | – |

| 40. OXC should be discontinued completely before starting treatment with ESL; combining these 2 drugs provides few benefits. | |||

| First round | 9 | 0.25 | Consensus of agreement |

RIR: relative interquartile range.

Questions and results from the section ‘Oxcarbazepine: situations favourable to switching’.

| Phase of the study | Median | RIR | Level of consensus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients who frequently forget to take their medication. | |||

| Second round | 8.5 | 0.26 | Consensus of agreement |

| 42. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients who work rotating shifts (schedule changes). | |||

| Second round | 8.0 | 0.28 | Consensus of agreement |

| 43. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in polymedicated patients with multiple conditions (taking several doses per day corresponding to different treatments). | |||

| Second round | 8.0 | 0.25 | Consensus of agreement |

| 44. Transition from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients with cognitive problems. | |||

| Second round | 7.5 | 0.13 | Consensus of agreement |

| 45. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients in whom combined treatment with OXC plus an SCB has failed to achieve seizure control. | |||

| First round | 4.0 | 1.00 | – |

| 46. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients in whom combined treatment with OXC plus an nSCB has failed to achieve seizure control. | |||

| First round | 8.0 | 0.28 | Consensus of agreement |

| 47. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients in whom combined treatment with OXC plus an enzyme-inducing AED has failed to achieve seizure control. | |||

| First round | 5.5 | 0.91 | – |

| 48. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients in whom combined treatment with OXC plus a non-enzyme-inducing AED has failed to achieve seizure control. | |||

| Second round | 7.0 | 0.14 | Consensus of agreement |

| 49. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in women of childbearing age. | |||

| Second round | 5.0 | 0.60 | – |

| 50. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in women of childbearing age who take contraceptives. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 0.80 | – |

| 51. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients with liver disease other than acute liver failure (including those with isolated elevations of GOT and GPT levels). | |||

| First round | 6.0 | 0.83 | – |

| 52. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients who had experienced a rash due to OXC use. | |||

| Second round | 2.0 | 1.00 | – |

| 53. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients with depressive symptoms. | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 0.80 | – |

| 54. Switching from OXC to ESL is recommended in patients with erectile dysfunction caused by OXC. | |||

| First round | 6.0 | 0.54 | – |

| 55. Would you recommend switching OXC to ESL in patients with severe osteopaenia–osteoporosis? | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 0.45 | – |

| 56. Would you recommend switching from OXC to ESL in patients with cardiovascular risk factors regardless of dyslipidaemia status? | |||

| First round | 5.0 | 0.65 | – |

RIR: relative interquartile range.

Regarding the drugs analysed in our study, the forms of presentation available in Spain are as follows: immediate-release CBZ tablets, 200mg and 400mg; immediate-release OXC tablets, 300mg and 600mg, plus an oral suspension 60mg/mL; and ESL tablets, 800mg.23–25

Field work and analysis of resultsThe study was conducted in 2 phases. During the first phase (21 January to 10 February 2015), the 54 panel members completed the questionnaire via an online platform; all responses were anonymous. Questions were answered on an ordinal scale of 1 to 10, with 0 indicating strong disagreement and 10 representing strong agreement. A consensus of agreement was considered to have been reached when responses for an item had a median ≥7 points and a relative interquartile range (RIR) of ≤0.40. On the other hand, consensus of disagreement was considered to have been reached when responses had a median of ≤3 points and an RIR of ≤0.40.

The coordination committee subsequently conducted a preliminary analysis of results. We agreed that the items meeting the target levels of agreement (median ≥7) or disagreement (median ≤3) but showing a high degree of dispersion of responses (RIR>0.40) would be included in the second round. In contrast, the second phase did not include those items with highly polarised responses, that is, with both a high degree of dispersion and medians well below or above the values for consensus of agreement (≥7) or disagreement (≤3).

During the second phase (17 March to 7 April 2015), the selected questions were resent to panel members using the online platform. Forty out of the 54 experts (74%) completed the questionnaire in the second round; the remaining 14 failed to answer the questions within the established period. In studies using the Delphi method and including a relatively high number of experts, as in our case, the number of participants frequently decreases from the first round to the second; results are nonetheless considered admissible. The purpose of the second phase was to reduce dispersion in the responses (RIR≤0.40) and therefore to reach a consensus for as many items as possible.

Lastly, the coordination committee held a video-conference in May 2015 to analyse the results of the second round, determined which questions reached a consensus of agreement/disagreement, drew a series of conclusions, and finalised the study.

ResultsResults for each of the questions are shown in Tables 1A–1D. We will now summarise the situations for which a consensus was reached.

Carbamazepine. Methodology for switchingAccording to most of the experts (62%), switching from CBZ to ESL overnight is an unnecessary risk that should be avoided: drug switching should be progressive (1 to 3 weeks), regardless of the prior dose of CBZ. Panel members also agreed that a CBZ:ESL dose ratio of 1:1.3 should be used (Table 1A).

Carbamazepine. Situations favourable to switchingSwitching from CBZ to ESL is recommended for patients who frequently forget to take their medication, those who work rotating shifts (schedule changes), polymedicated patients with multiple conditions (taking several doses per day corresponding to different treatments), patients with cognitive problems, patients with severe osteopaenia–osteoporosis, patients with dyslipidaemia or liver disease other than acute liver failure (including those with isolated increases in GOT and GPT levels), and men with erectile dysfunction caused by CBZ. A consensus of disagreement was reached on switching from CBZ to ESL in patients experiencing a rash attributable to CBZ.

Experts also reached a consensus on drug switching in patients who did not achieve seizure control with the following dual therapy options: CBZ+non-sodium channel blocker (nSCB), CBZ+enzyme-inducing AED, and CBZ+non-enzyme-inducing AED. A consensus of disagreement was reached on switching from CBZ to ESL in patients receiving dual therapy with CBZ plus a sodium channel blocker (SCB) (Table 1B).

Oxcarbazepine. Methodology for switchingPanel members agreed that transition from OXC to ESL can be done overnight: patients should take the total dose of ESL at night, after taking the normal dose of OXC in the morning. They recommended an OXC:ESL dose ratio of 1:1. OXC should be discontinued before switching to ESL due to the low utility of combining these 2 drugs (Table 1C).

Oxcarbazepine. Situations favourable to switchingPanel members recommended switching from OXC to ESL in patients who frequently forget to take their medication, those who work rotating shifts (schedule changes), polymedicated patients with multiple conditions (taking several doses per day corresponding to different treatments), and patients with cognitive problems. There was a consensus of disagreement on switching CBZ to ESL in patients experiencing a rash attributable to CBZ.

Likewise, experts agreed on switching to ESL in patients who had not achieved seizure control with a combination of OXC plus a non-enzyme-inducing AED or an nSCB (Table 1D).

DiscussionCarbamazepine. Methodology for switchingThe consensus reached by panel members on the CBZ:ESL dose ratio (1:1.3) is in line with the recommendations made by Peltola et al.19 and Massot et al.26 Concurring with Peltola et al.,19 experts agreed that a minimum period of 1 to 3 weeks was necessary for drug switching. Hospitalised patients are the only ones in whom drugs may be switched overnight,26 but this situation was not evaluated in our study. There was no consensus of either agreement or disagreement regarding complete withdrawal of CBZ when starting treatment with ESL. In this situation, both options should be considered, keeping in mind that although concomitant use of CBZ and ESL has been associated with significant increases in the rate of adverse effects,27 over 55% of the patients in phase-3 clinical trials received CBZ and ESL simultaneously.9–13

Carbamazepine. Situations favourable to switchingPanel members reached a consensus of agreement on switching from CBZ to ESL in patients with poor compliance (patients frequently forgetting to take their medication or those working shifts). ESL has a half-life of 20 to 24 hours28 and is taken as a single daily dose; in contrast, immediate-release CBZ (12-17h after regular administration) requires 2 to 3 doses per day.24 This format is available in Spain. Switching to ESL was also recommended for polymedicated patients with multiple conditions (those taking several doses per day corresponding to different treatments), in order to simplify antiepileptic treatment to a single daily dose.29 Drug switching was also recommended for patients with cognitive impairment. Several studies have shown that CBZ has a negative impact on multiple cognitive domains,30 especially information processing and the ability to concentrate.31 In contrast, ESL usually causes fewer cognitive adverse effects (3.3%-9.8%).17,26,32

Transitioning from CBZ to ESL was also considered appropriate in patients whose medication failed to control seizures, those receiving CBZ plus an enzyme-inducing AED or a non-enzyme-inducing AED, and those treated with CBZ plus an nSCB; drug switching was not recommended for patients on dual therapy with CBZ+SCB. In a study conducted in the clinical practice setting, the percentage of responders increased when ESL was combined with an nSCB (66.7% vs 44.7%).17 The fact that ESL's action mechanism on sodium channels (slow inactivation) is different from that of CBZ, in addition to differences in other pathways (hCaV3.2 currents), may explain the decision for recommending combined treatment with ESL plus other drugs with the same action mechanism.16 Furthermore, the enzyme-inducing effect of ESL is less marked than that of CBZ, which may explain the decision to combine ESL with an enzyme-inducing drug.23,24

No consensus was reached on the suitability of drug switching in women of childbearing age. Some enzyme-inducing drugs, such as CBZ, have been found to increase the levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), leading to a decrease in oestradiol levels that may affect sexual function and fertility.33 However, the scarcity of data on pregnant women taking ESL may explain this lack of consensus. No consensus of agreement or disagreement was reached on drug switching in women of childbearing age taking contraceptives. CBZ has been shown to increase the metabolism of ethinyloestradiol and progestogens. Levonorgestrel implants are contraindicated in women treated with CBZ.34 ESL has also been found to decrease exposure to ethinyloestradiol and progestogens.35 In men, CBZ may reduce testosterone levels33 and increase SHBG levels, leading to a decrease in the free androgen index and dehydroepiandosterone levels.36,37 These effects have been described in patients taking enzyme-inducing AEDs, for example CBZ, and may lead to sexual dysfunction in men.38 Panel members agreed on the suitability of switching from CBZ to ESL in patients with erectile dysfunction given that ESL has a less powerful enzyme-inducing effect.14,39

Regarding the switch from CBZ to ESL and abnormal analytical parameters, the following conclusions can be drawn from our results: 1) panel members agreed that CBZ may be switched to ESL in patients with dyslipidaemia. CBZ has been associated with significant increases in levels of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL).40 According to a study by Gil-Nagel et al.,13 the effects of ESL on triglyceride and cholesterol levels were similar to those of a placebo. Furthermore, recent data gathered in a clinical practice context suggest that switching from CBZ to ESL may decrease LDL and triglyceride levels.412) Experts reached no consensus on drug switching in patients with hyponatraemia caused by CBZ. According to a study by Dong et al.42, 13.5% of the patients treated with CBZ displayed hyponatraemia, compared to 1.5% to 8.8% of those receiving ESL9–13; we should bear in mind, however, that these 2 studies included different populations. A recent retrospective study reported improvements in patients with hyponatraemia when they switched from CBZ or OXC to ESL; however, only a few patients were included in this study.433) Experts reached a consensus of agreement on switching from CBZ to ESL in patients with liver disease (including those with isolated increases in GOT and GPT levels) other than acute liver failure. A study by Hussein et al.44 found a statistically significant negative correlation between duration of CBZ treatment and GOT and GPT levels; alterations in liver parameters were below 1% in clinical trials of ESL.13

Lastly, the lack of comparative studies for CBZ and ESL and experts’ clinical experience may justify the consensus of disagreement on drug switching in patients who had experienced a rash due to CBZ. In contrast, transitioning from CBZ to ESL was recommended in patients with severe osteopaenia–osteoporosis because of changes in bone metabolism. The powerful enzyme-inducing effect of CBZ is linked to a significant decrease in bone mineral density along with increased risk of bone fracture.45 More specifically, the study by Vestergaard46 reported an odds ratio (OR) of 1.18 for fracture risk due to CBZ. The lower enzyme-inducing capacity of ESL may prevent fractures, although no long-term studies have been conducted to support this hypothesis.

Oxcarbazepine. Methodology for switchingAccording to panel members, OXC may be switched to ESL overnight. Other authors have also supported this methodology for drug switching,18,26 including Peltola et al.19 This may be explained by similarities between the metabolic pathways of OXC and ESL. In line with the literature, panel members agreed that the full dose of ESL should be taken at night after having taken the morning dose of OXC, with an OXC:ESL ratio of 1:1.18,19,26,29 A consensus of agreement was reached regarding withdrawing OXC completely after starting treatment with ESL because of poor response to this drug combination.

Oxcarbazepine. Situations favourable to switchingImmediate-release OXC (available in Spain) is administered in 2 to 3 daily doses to minimise the adverse effects associated with high doses.47 Therefore, and with the aim of improving adherence by reducing the number of doses,48 panel members recommended switching OXC to ESL in patients who frequently forget to take their medication, those who work rotating shifts (schedule changes), and polymedicated patients with multiple conditions (taking several doses per day corresponding to different treatments). Furthermore, experts recommended switching to ESL in patients with cognitive problems, given the low frequency of cognitive adverse effects associated with this treatment.29 Randomised clinical trials of both drugs have shown that ESL is linked to fewer neurological adverse effects than OXC.49 On the other hand, a study of healthy volunteers showed an earlier peak in CSF and plasma drug concentrations after OXC administration than after ESL administration, which may point to poorer tolerability in the case of OXC.15 Lastly, a study conducted in the clinical practice setting showed improvements in tolerance in over half of the patients who had switched from OXC to ESL due to adverse effects.17

Drug switching was also recommended in patients who did not achieve seizure control with dual therapy (OXC plus a non-enzyme-inducing AED or OXC plus an nSCB). ESL's different action mechanism in sodium channels (slow inactivation) compared to OXC may explain the decision to combine ESL with other drugs.50 There is no scientific evidence to either support or advise against combined treatment with ESL plus other AEDs based on the different enzyme-inducing properties of ESL and OXC.

Lastly, the lack of comparative studies of OXC and ESL, experts’ clinical experience, and similarities in the metabolic pathways of these 2 drugs may explain why panel members did not recommend drug switching in patients who had experienced a rash due to OXC. Returning to the subject of altered bone metabolism, OXC administration has been associated with bone fractures (OR 1.14).46 However, no consensus was reached on drug switching in patients with severe osteopaenia–osteoporosis; this is probably due to the lack of long-term results for ESL.

Our study has several limitations as well as a number of strengths. Limitations include the lack of a high level of evidence (our results summarise experts’ opinions based on the Delphi method), the arbitrariness and subjectivity of the questionnaire items (which do not analyse all aspects of treatment exhaustively), and the fact that not all members of the panel participated in the second round. The greatest strengths of our study are that recommendations are based on the opinions of numerous epilepsy experts using a novel research technique (Delphi method), and that we have contributed data in a field in which very little evidence can be considered useful for clinical practice.

ConclusionsBased on the Delphi method, our study systematically reviews certain clinical situations in which a group of Spanish experts in epilepsy would recommend switching CBZ or OXC to ESL. Although our study does not end debates revolving around some situations, it does provide recommendations for clinical management in the context of switching from CBZ or OXC to ESL treatment.

Conflicts of interestThis study has received funding from Bial and Eisai for editing and publishing purposes. Neither of these pharmaceutical companies participated in question selection, analysis of results, or drafting of the manuscript.

We would like to thank the 54 panel members participating in the EPICON project:

Drs Ainhoa Marinas (Hospital Universitario Cruces, Bilbao), Albert Molins (Hospital Universitario Josep Trueta, Girona), Alberto García (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias), Alberto Moral (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias), Álex García (Hospital Imed Levante, Benidorm), Ana Piera (Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valencia), Antonio Moreno (Hospital Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca), Antonio Oliveros (Hospital Reina Sofía de Tudela), Arantxa Alfaro (Hospital La Vega Baja, Orihuela), Ascensión Castillo (Hospital General Universitario, Valencia), Asier Gómez (Hospital Universitario La Fe, Valencia), Carmen Arenas (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla), Clara Cabeza (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Toledo), David Sopelana (Hospital General Universitario Albacete), Diego Tortosa (Hospital Universitario Arrixaca, Murcia), Dulce Campos (Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valladolid), Emilio Martínez (Hospital Comarcal de Vinaroz), Francisco Javier López (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario, Santiago), Francisco Villalobos (private clinic, Sevilla), Guillermina García (Hospital Clínico de Málaga), Guillermo Rubio (private clinic, Jerez de la Frontera), Íñigo Garamendi (Hospital Universitario Cruces, Bilbao), and Javier Montoya (Hospital Lluis Alcanyis, Xàtiva).

Jerónimo Sancho (Hospital General Universitario, Valencia), José Ángel Mauri (Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa), José Carlos Giner (Hospital General Universitario, Elche), José María Serratosa (Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid), Juan Carlos Sánchez (Hospital Clínico Universitario San Cecilio, Granada), Juan José Poza (Hospital Universitario Donosti), Juan Luis Becerra (Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujols, Badalona), Juan Mercadé (Hospital Universitario Carlos Haya, Málaga), Juan Palau (Hospital de Manises, Valencia), M. Eugenia García (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid), Macarena Bonet (Hospital Universitario Arnau Vilanova, Valencia), Manuel Domínguez (Clínica La Milagrosa, Madrid), Manuel Toledo (Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona), Mar Carreño (Hospital Clínic Universitario, Barcelona), and M. José Aguilar-Amat (Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid).

Marta Agúndez (Hospital Universitario Cruces, Bilbao), Mercè Falip (Hospital Universitario Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat), Mercedes Garcés (Hospital Universitario La Fe, Valencia), Nuria García (Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid), Óscar Vega (Hospital Cruz Roja, Córdoba), Pablo Quiroga (Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas, Almería), Pedro Bermejo (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro), and Pedro Quesada (Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra).

Rafael Toledano (Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid), Raúl Amela (Hospiten Roca, Gran Canaria), Rosa Querol (Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina, Badajoz), Vicente Bertol (Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza), Xavier Salas (Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona), and Xiana Rodríguez (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario, Santiago).

We also wish to thank Entheos for their help in planning, field analysis, and analysis of results.

Please cite this article as: Villanueva V, Ojeda J, Rocamora RA, Serrano-Castro PJ, Parra J, Rodríguez-Uranga JJ, et al. Consenso Delphi EPICON: recomendaciones sobre el manejo adecuado del cambio a acetato de eslicarbazepina en epilepsia. Neurología. 2018;33:290–300.