Dopa-responsive dystonia (DRD) encompasses a group of clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorders typically presenting with appendicular dystonia, generally in the lower limbs, which fluctuates throughout the day and may spread to other parts of the body, and even progress with parkinsonian signs. As the name indicates, it improves with levodopa treatment.1,2

It is typically caused by genetic defects of enzymes involved in dopamine biosynthesis, and may follow either an autosomal dominant (eg, GCH1-associated forms) or an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern (eg, forms caused by mutations in TH, SPR, or PTP). Some cases are caused by genetic disorders unrelated to dopamine synthesis, for instance in hereditary spastic paraplegia type 11, spinocerebellar ataxia type 3, and ataxia-telangiectasia.1

We present the case of a patient with DRD in whom 2 different mutations were identified, one affecting the parkin gene (PRKN) and the other affecting sepiapterin reductase (SPR).

The patient is a 22-year-old woman. She has no family history of neurological disease. She first presented symptoms at the age of 14 years, with involuntary inversion of the right foot, which hindered gait. Neurological examination identified dystonic posture (inversion) of the right foot, increased muscle tone in the right leg, and tremor during the Mingazzini manoeuvre, with no other alterations. Levodopa treatment achieved a significant improvement, and the patient was diagnosed with DRD; a genetic study of GCH1 was requested, yielding negative results.

In the following months, the patient developed impaired coordination of the right hand. Physical examination revealed bradykinesia and rigidity of the right hand, and reduced arm swing. She dragged the right foot when walking. An expanded genetic study was performed; no HTT mutation was identified, but mutations were detected in PRKN (c.1204 C>T) and SPR (c.308 C>G). Both mutations were heterozygous and of uncertain significance. The PRKN and SPR mutations were detected in the patient’s father and mother, respectively; both parents were asymptomatic.

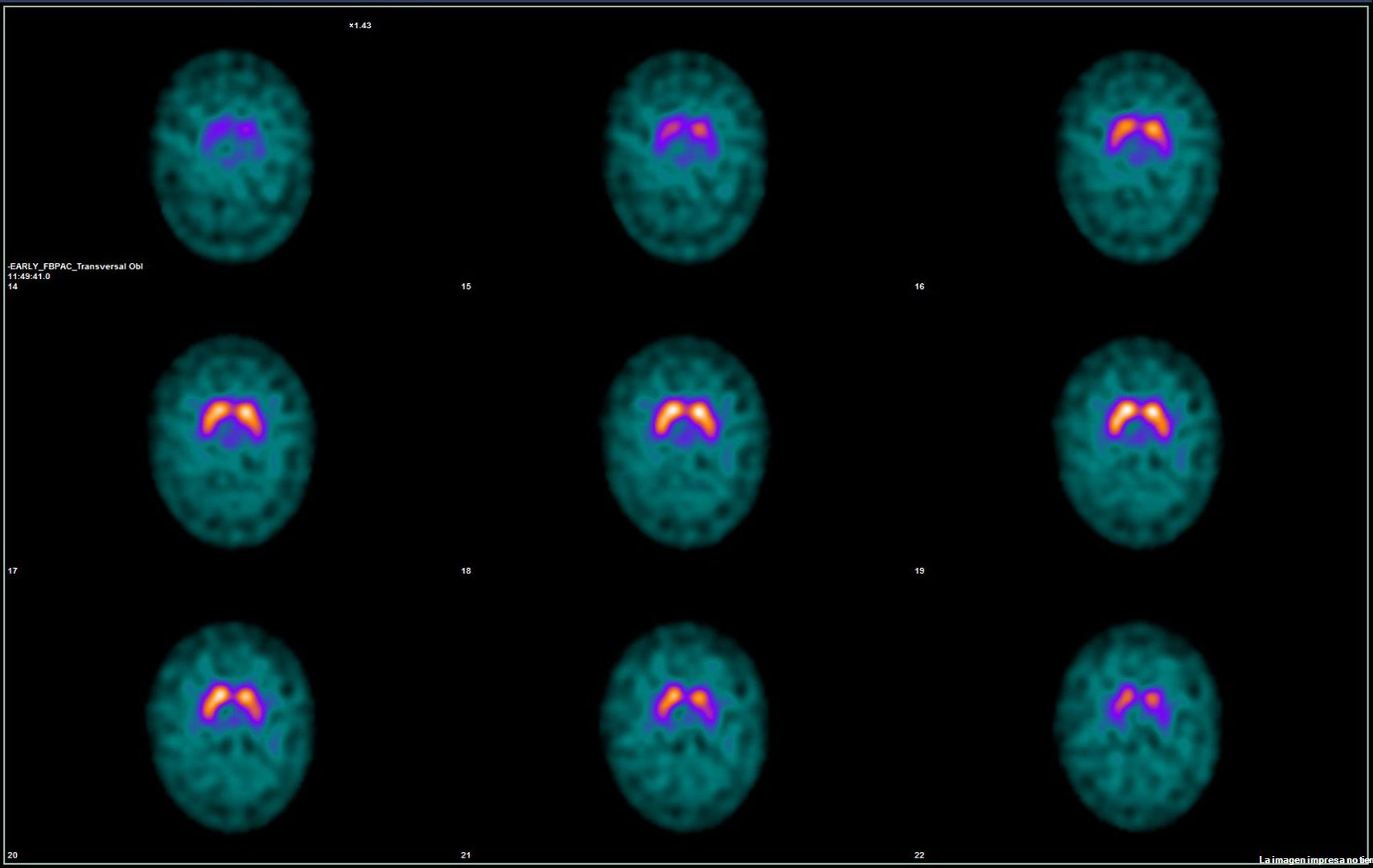

Symptoms subsequently progressed with increased rigidity on the right side and bilateral bradykinesia with right predominance; therefore, levodopa dose was increased. The patient also reported hyposmia and dysgeusia. Furthermore, she was diagnosed with neurogenic bladder. Findings from a DaTSCAN study (Fig. 1) and a 123I-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy study were normal.

The patient did not tolerate a further dose increase, and was referred to the movement disorders unit. Botulinum toxin infiltration of the right tibialis posterior muscle achieved no improvement. The patient agreed to undergo deep brain stimulation (DBS), and electrodes were implanted in the internal globus pallidus bilaterally. Prior to the intervention, she had a Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor score of 45 in the OFF state and 35 after levodopa administration. The patient improved significantly with DBS, with initial stimulation parameters of 1.5 mA, 60 s, and 130 Hz bilaterally, progressively increasing over 8 months up to 3.8 mA; stimulation achieved a UPDRS motor score of 0, allowing discontinuation of the medication. She continues to present occasional dystonia of the foot.

DRD can result from sepiapterin reductase deficiency, which typically displays an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, and reduces the production of BH4, a key cofactor in dopamine synthesis.1–4 It generally causes movement disorders, oculogyric crises, and intellectual disability in the early years of life in patients inheriting 2 pathogenic alleles.1,3,4

Furthermore, PRKN mutations are the most frequent cause of juvenile parkinsonism,5 which also follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. These mutations cause a defect in parkin, a ubiquitin ligase involved in mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis.5

One case has been reported of DRD without parkinsonian signs in a heterozygous carrier of a PRKN mutation6; another report describes a case of DRD in a patient heterozygous for an SPR mutation.7

However, as neither of our patient’s parents were symptomatic, we believe that her symptoms may be explained by the simultaneous presence of these 2 mutations in heterozygosis. A literature search identified no other cases with this form of presentation.

DBS is an effective symptomatic treatment for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease8 and, though with a lower level of evidence, appears also to be effective for hereditary parkinsonism.9 Pallidal DBS has been shown to be useful in treating dystonia,10 including dopa-responsive forms.11 This was also the case in our patient; therefore, this option should be considered in patients who are unresponsive or intolerant to pharmacological treatment.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors of this study meet the ICMJE authorship criteria and made substantial contributions to study conceptualisation and design; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and drafting and review of the manuscript.

Informed consentThe patient gave informed consent to the publication of this study.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

None.