Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is a rare cause of stroke. To date, some cases have been reported in association with SARS-CoV-2 infection, which appears to increase the incidence of thrombotic phenomena.1–4 We present a patient with bilateral chorea as an initial symptom of COVID-19–associated CVST. The patient was a 69-year-old woman with history of fatty liver disease and fibromyalgia, who was admitted to hospital with bilateral pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2 infection; she tested positive for IgG antibodies and was under prophylactic treatment with enoxaparin sodium. On day 21, she awoke with mixed aphasia, mild right hemiparesis, and choreic movements in all 4 limbs (video in Supplementary material), leading to in-hospital code stroke activation.

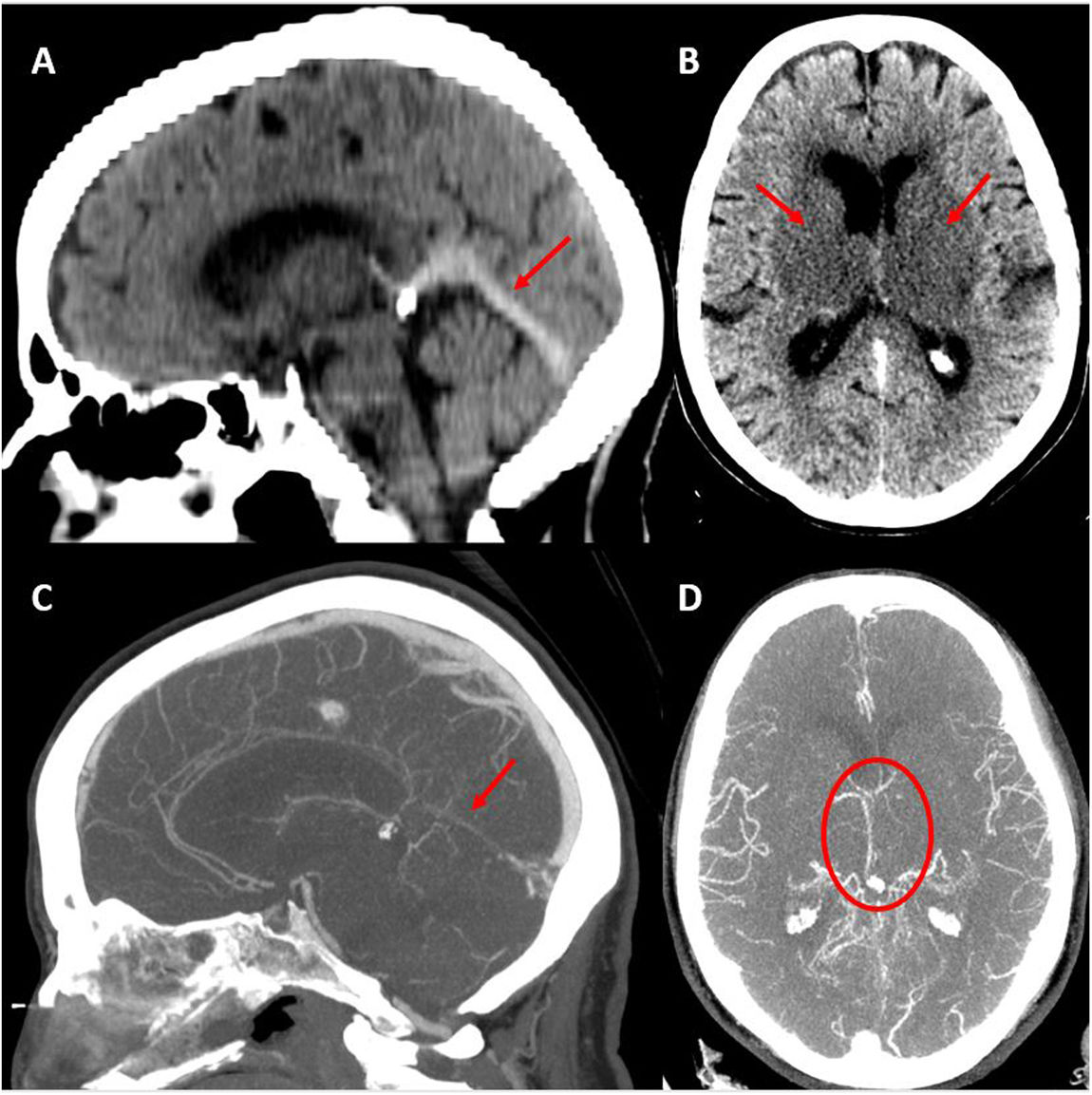

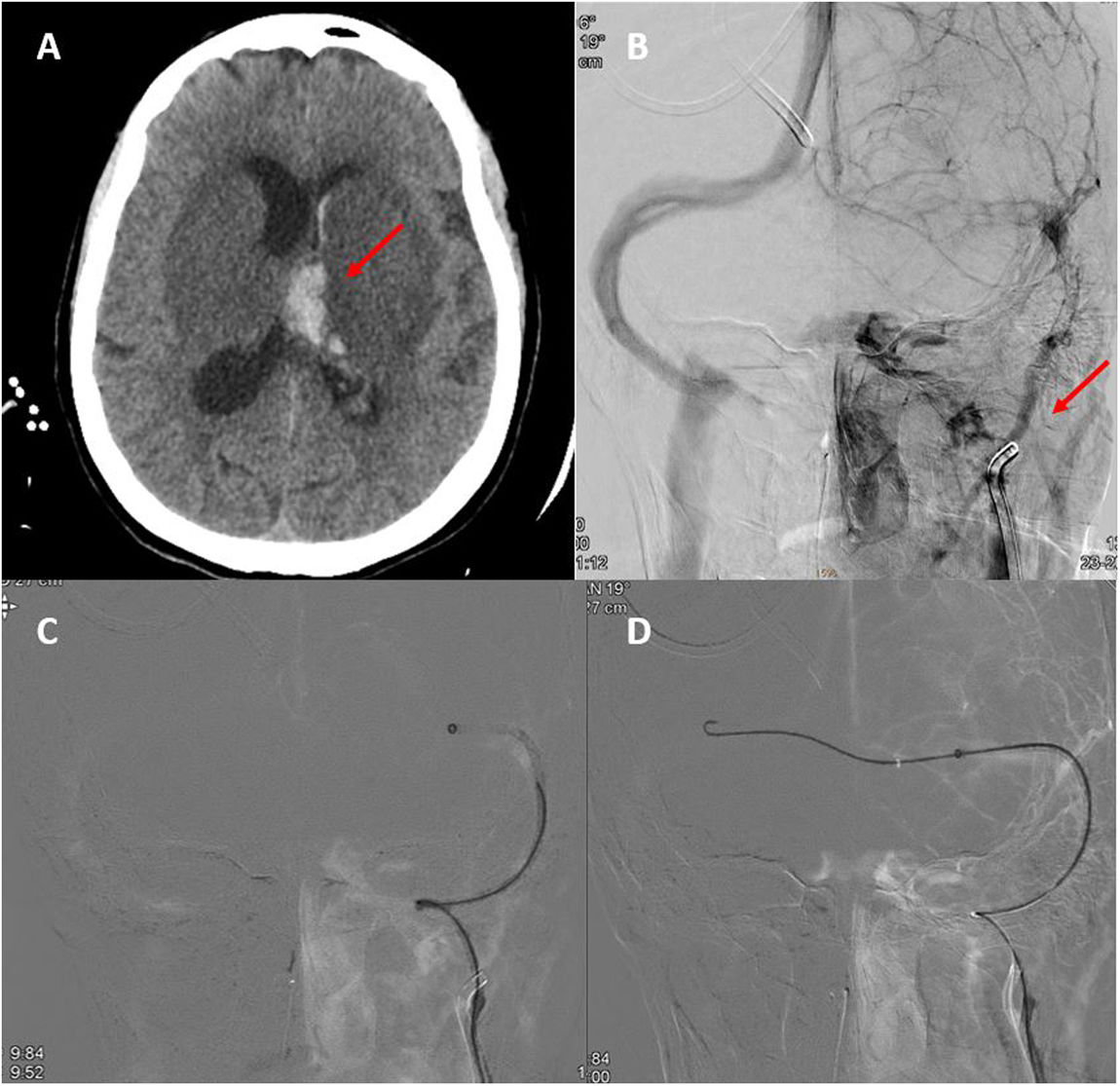

The CT/CT angiography study (Fig. 1) identified capsuloganglionic and thalamic infarcts bilaterally, with thrombosis of the lateral veins, left lateral sinus, straight sinus, and vein of Galen. Blood analysis showed elevated d-dimer levels (3160 μg/L), without thrombocytopaenia. The patient was prescribed anticoagulation with enoxaparin. Progression over the following 24 hours was unfavourable, with persistence of choreic movements and a progressive decrease in the level of consciousness. A second head CT study (Fig. 2A) suggested haemorrhagic transformation of the left thalamic infarct.

Baseline head CT scan. A) Hyperdensity of the straight sinus. B) Bilateral capsuloganglionic and thalamic infarcts. Contrast-enhanced CT angiography, venous phase. C) Lack of opacification of the straight sinus. D) Poor opacification of the deep venous system, predominantly on the left side.

A) Second head CT scan, showing haemorrhagic transformation of the left thalamic infarct. B) Neuroangiography study showing irregular opacification of the left internal jugular vein and lack of opacification of the distal ipsilateral venous system. C and D) Neuroangiography study showing the passage of the guidewire and thrombectomy catheter from the right to the left transverse sinus across the torcular Herophili.

In the light of the clinical worsening, we decided to perform arteriography and mechanical thrombectomy, achieving partial recanalisation (Fig. 2B). During the procedure, the patient presented a hypertensive peak with arreactive bilateral mydriasis, which persisted despite measures to reduce oedema. An additional head CT scan showed no changes with respect to the previous study. The patient eventually died. We were not able to collect blood samples for antiphospholipid antibody determination or a thrombophilia study.

This case presents 2 noteworthy characteristics. The first is the association between CVST and COVID-19. CVST accounts for 0.5% to 1% of cases of stroke, with an estimated incidence of 1.6 cases per 100 000 person-years. It usually affects young patients, with a woman-to-man ratio of 3:1.5,6 Risk factors include hormonal factors, inherited or acquired hypercoagulable states, and infections.5 Clinical presentation depends on the territory involved; the most frequent symptoms are headache, focal neurological deficits, seizures, and diffuse encephalopathy. Treatment with low–molecular weight heparin is recommended, although the ideal treatment duration and the role of oral anticoagulants are not well established.6 Endovascular treatment should be considered in severe cases with clinical worsening or lack of improvement despite anticoagulation treatment, and is associated with a higher rate of intracranial haemorrhagic complications.5,6

In the last year, SARS-CoV-2 infection has been associated with an increased risk of thrombotic events, including CVST. While deep vein thrombosis and arterial thrombosis appear to be more common in patients with moderate-severe respiratory tract infections, CVST also occurs in patients with mild symptoms. Among the reported cases, incidence appears to be similar between sexes; patients tend to be middle-aged and not present relevant comorbidities.1–4 The risk of thrombotic events persists for several weeks after resolution of infectious symptoms.7 Thrombosis associated with COVID-19 seems to be explained by endothelial damage mediated by the virus’ interaction with the ACE2 receptor; the inflammatory response, which causes an increase in cytokines associated with hypercoagulable states; and transient presence of prothrombotic antibodies, such as antiphospholipid antibodies.2–4,7 The latter phenomenon has also been observed in acute infection with varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, and parvovirus B.3 Laboratory studies often show elevated d-dimer and C reactive protein levels; presence of other markers of thrombotic risk is variable.4,7

Patients with CVST associated with COVID-19 present greater prevalence of deep vein thrombosis. This factor may be associated with poorer prognosis, as higher mortality rates have been observed in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (even mild cases) plus CVST with respect to patients with only one of these conditions.4 Regarding management, early anticoagulant therapy constitutes the central pillar of treatment.1–4,7 The most appropriate drug and treatment duration have not yet been established.1

The second interesting aspect of this case is the association between CVST and bilateral chorea. Stroke rarely causes movement disorders. Small-vessel disease and small, deep infarcts, and more frequently haemorrhagic stroke, are the types of stroke most commonly associated with these disorders.8–10 Among the movement disorders reported as manifestations of stroke, hemichorea/hemiballismus is the most common; nevertheless, it occurs in fewer than 1% of patients with acute stroke. Chorea is unilateral in 90% of cases,8,9 and is caused by lesions affecting the thalamus or basal ganglia.8

Therefore, we should be alert to the increased risk of CVST in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and new-onset focal neurological signs, and start early anticoagulant therapy, given the poor prognosis. The most appropriate anticoagulant drug and treatment duration have not yet been established. Furthermore, while chorea is the most frequent movement disorder after stroke, the literature includes few cases of bilateral involvement. In the case of CVST, involvement of the deep venous system promotes the appearance of chorea.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Revert Barberà A, Estragués Gazquez I, Beltrán Mármol MB, Rodríguez Campello A. Corea bilateral como forma de presentación de trombosis venosa cerebral asociada a COVID-19. Neurología. 2022;37:507–509.