Based on the SECI knowledge transformation model and the double-loop learning model, we analyze the path and mechanism of transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the individual, organizational, and systemic levels. Furthermore, the transformation mechanisms for different entrepreneurial types, fields, and failure costs are compared. (1) There are two transformation paths—Path 1: entrepreneurial failure experiences → resource integration → entrepreneurial learning → entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities, and Path 2: entrepreneurial failure experiences → entrepreneurial social networks → resource integration → entrepreneurial learning → entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities. (2) The transformation modes at the individual, organizational, and systemic levels are experiential, exploratory, and cognitive learning, respectively. (3) At both the individual and organizational levels, individual entrepreneurial networks exert a stronger effect than team entrepreneurial networks. At the systemic level, team entrepreneurial networks exert a greater influence. (4) During the transformation process, the degree of influence of entrepreneurial social networks, learning modes, and knowledge transformation outcomes varies across different entrepreneurial types, fields, and failure costs.

According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM): 2024–2025 Global Report on Entrepreneurship, the entrepreneurial economy’s contribution to national economic and social development is steadily rising and is gradually becoming a key driver of regional economic growth. However, a high failure rate is a characteristic feature of widespread entrepreneurship (Boso et al., 2019). For example, in China less than 10 % of annual new ventures operate for more than three years, and the failure rate of college student entrepreneurship is as high as 99 % (Newman et al., 2022). According to Williams et al. (2020), the identification and utilization of entrepreneurial opportunities contribute the most to the performance of new ventures. Additionally, entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial learning are the key factors influencing the performance of subsequent ventures following failure. Enhancing the entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities and resource integration ability of entrepreneurs—both closely related to entrepreneurial social networks—can further increase the success rate of subsequent ventures (Brown et al., 2019). For serial entrepreneurs, analyzing the causes of their failure can help them identify and understand the factors and problems that led to the failure, enabling them to better adjust and improve their business models, marketing strategies, and team management, while also recognizing the limitations of their own decisions and the influence of external factors. Huang et al. (2020) argue that failure attribution is crucial for entrepreneurs who were unsuccessful in their first venture. Entrepreneurs who made internal attributions and changed their behaviors either permanently returned to paid employment or established successful enterprises. In contrast, those who made external attributions founded multiple unsuccessful ventures and often repeated their errors. Ioanna et al. (2019) suggest a potential connection between internal and external attributions of entrepreneurial failure, indicating that the two can be transformed into each other. Controllable external environmental factors tend to make entrepreneurs recognize that their actions can change outcomes, thereby promoting internal and controllable attributions of entrepreneurial failure and ultimately motivating them to pursue new entrepreneurial ventures.

Existing studies have noted that entrepreneurial social networks, as a factor influencing entrepreneurial success or failure, can help entrepreneurs reduce information asymmetry, thereby effectively promoting the transformation of failure experiences (Martin & Javalgi, 2019). Therefore, in the context of a high entrepreneurial failure rate, examining how entrepreneurs can transform their entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge through their social networks, thereby enhancing their entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities is crucial.

The most important success factor is the ability to extract new knowledge from past mistakes and apply it in a more productive manner (Alkharafi, 2024). However, owing to anti-failure bias (Kim & Jin, 2024), most entrepreneurs focus solely on learning from successful enterprises rather than extracting insights from their own failures. Simmons et al. (2019) classified knowledge into tacit and explicit knowledge, both of which can interchangeably transform under certain circumstances, and proposed the Socialization, Externalization, Combination, Internalization (SECI) knowledge transformation model. However, the SECI only considers the transformation of knowledge itself, without considering the impact of social networks. Banerjee et al. (2022) observed that alongside single- and double-loop learning, transformational and creative learning are also important. Khalid et al. (2022) found that the specific context of learning influences the content of learning. In particular, the prioritized learning content of entrepreneurs is significantly bound to the characteristics of different industries. Simmons et al. (2019) illustrated that entrepreneurs’ knowledge structure, prior experiences, attribution styles, and emotions significantly impact their learning transformation process. Wei (2022) believed that the cost of entrepreneurial failure can promote entrepreneurs’ learning. However, if the cost is low, entrepreneurs may not acquire knowledge from failing. Oluwabunmi et al. (2020) analyzed how entrepreneurs learn from their failures and developed an entrepreneurial learning model. They divided the learning process into three sub-processes: outcome generation, failure identification and failure correction. Leadership behaviors (Yu, 2020), entrepreneurial orientation (Zhu et al., 2019), and self-efficacy (Michael & Deborah, 2019) are believed to have moderating effects on the transformation of entrepreneurial experiences in the organizational system. Moreover, scholars have conducted research on the knowledge transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences, mainly focusing on two aspects—the relationship between entrepreneurial failure experience and re-entrepreneurship performance and a summary of such experiences. Zhang et al. (2021) studied the transformation and flow of tacit knowledge based on the perspective of knowledge acquisition and observed that tacit knowledge is the root element that determines the technological innovation ability of enterprises. Leandro and Viviane (2020) studied the two-dimensional structure of organizational knowledge transformation across different subject levels, exhibiting that personal traits are the antecedent variables influencing knowledge transformation. Michaelides and Davis (2020) studied the modes of entrepreneurial failure learning and found that internal learning is preferred for high-tech industries, while self-learning and external learning are preferred for non-high-tech industries. Yin et al. (2020) analyzed the promotion mechanism of dynamic abilities in the process of knowledge transformation, especially the comparison between different dimensions. Cahn et al. (2021) studied the relationship between entrepreneurial failure experience, organizational learning and subsequent entrepreneurial intentions. The results illustrate that internal attribution learning and external learning can improve the efficiency of double-loop learning and single-loop learning, respectively. Trubnikov (2021) studied the knowledge leap from imitative innovation to independent innovation and highlighted the differences between the two.

Although considerable empirical testing and theoretical analysis have been conducted on the impact of entrepreneurial failure on serial entrepreneurial performance, notable gaps and areas for further research remain. The research objectives and innovations of this study are as follows. First, the path mechanism of transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge is improved. Existing studies on entrepreneurial failure primarily focus on its on serial entrepreneurial performance. Additionally, research on mediating variables primarily centers on the roles of entrepreneurial resilience, context, and recovery. However, there is relatively little research on entrepreneurial knowledge, despite it being one of the most significant factors influencing the entrepreneurial performance of serial entrepreneurs. This study first, theoretically identifies the paths and mechanisms through which entrepreneurial failure experiences are transformed into entrepreneurial knowledge. Second, the breadth and depth of the existing research is expanded. Although many scholars have emphasized the importance of entrepreneurial social networks for transforming entrepreneurial knowledge, most existing studies remain confined to the perspective of “individual entrepreneurial social networks” and overlook the role of “team entrepreneurial social networks.” This study expands from a single individual social network to a dual network perspective that includes both individual and team networks. It conducts an in-depth analysis of the transformation paths and mechanisms under the dual network framework, thereby making the research more comprehensive and logically coherent. Third, there is a need for more comprehensive research on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure into entrepreneurial knowledge across different contexts. Existing studies—whether based on single-loop learning, double-loop learning, or the SECI model— remain largely paradigmatic and lack pertinence. They fail to analyze the moderating effect of specific contextual factors. Accordingly, this study analyzes the paths and mechanisms of transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge under different entrepreneurial types, fields, and failure costs.

Therefore, in this study, the entrepreneurial social network is classified into individual and team entrepreneurial social networks. We analyze the path and mechanisms through which entrepreneurial failure experiences are transformed into entrepreneurial knowledge at the individual, organizational, and systemic levels, focusing on the mediating role of entrepreneurial social networks. Furthermore, we examine the transformation mechanisms of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge under different entrepreneurial types, fields, and failure costs.

This study is organized into six sections. In Section 2, we define the main research concepts. Next, we analyze the path and mechanism of transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the individual, organizational, and systemic levels and propose a conceptual model. Section 3 presents the questionnaire design, data collection, and analysis procedures. In Section 4, we empirically test the transformation path and mechanism using a simultaneous equation model and a structural equation model. In Section 5, we discuss the mechanism of transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge across different entrepreneurial types, fields, and failure costs. Section 6 concludes the study and reports the limitations and suggestions for future research.

Theoretical frameworkDefinitions of core research conceptsEntrepreneurial social network (SN). Social networks refer to relatively stable relationship systems formed through interactions between individual members of society. In this study, we classify entrepreneurial social networks into individual entrepreneurial social networks (PSN) and team entrepreneurial social networks (TSN). Individual entrepreneurial social networks refer to the social networks formed through entrepreneurs’ personal connections with the outside world (James et al., 2021), including the social network scale (PSNS), social network density (PSND), social network heterogeneity (PSNI), and social network connection strength (PSNC). Team entrepreneurial social networks refer to the networks formed through an entrepreneurial team’s external connections. These primarily include the team’s internal networks (TSNI, communication and learning within the team), external networks (TSNO, the connection strength and structure of the entrepreneurial team with the outside), and cross-team networks (TSNC, the viscosity intensity or the competitive relationship between entrepreneurial teams of the substitute or complementary industries). Based on the dual-path framework, entrepreneurial social networks form the pre-support for resource integration. They provide information exchange channels, resource connection platforms, and learning and communication spaces for entrepreneurs and their teams. The differentiated roles of individual and team entrepreneurial social networks across different levels directly affect the efficiency and direction of resource integration.

Entrepreneurial failure experience (FE). Owing to the differences in research perspectives and the ambiguity surrounding certain concepts (corporate closure, bankruptcy, etc.), scholars have not yet reached a consensus on the definition of entrepreneurial failure, resulting in inconsistencies in the conceptualization of entrepreneurial failure experience (Boso et al., 2019). There are three perspectives on the study of entrepreneurial failure experiences: resource (García et al., 2017), learning (Stambaugh & Mitchell, 2017), and emotional (Artinger & Powell, 2016) perspectives. The resource perspective emphasizes that entrepreneurial failure experience involves the acquisition and utilization of human resources and opportunities following venture failure. The learning perspective emphasizes that entrepreneurial failure experience improves capabilities for future entrepreneurial efforts. The emotional perspective emphasizes that entrepreneurial failure represents a psychological loss (emotion, confidence, etc.) experienced by entrepreneurs as a result of failure. Drawing from the three perspectives, entrepreneurial failure experience includes the use of external resources (FER), the accumulation of entrepreneurial capabilities (FEP), and the impact of cognitive emotional value (FEF). As the foundational basis for resource integration and social networks, the multi-dimensional connotations contained in entrepreneurial failure experience provide a differentiated transformation basis: the experience of utilizing external resources can more easily enter social networks directly through resource integration; while the summary of entrepreneurial ability experience and the influence of cognitive emotions are more dependent on the transmission and filtering of social networks, thus becoming the core input of resource integration.

Entrepreneurial dynamic capability (EC). Entrepreneurial capability is a set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that entrepreneurs possess to improve venture success. It is a multidimensional concept. Currently, definition of entrepreneurial capability often equate external resources with a firm’s competitive advantages, neglecting their actual utilization. A firm’s development is considered a static process that ignores the impact of dynamic changes (Rui et al., 2018). Referring to the study by Cahn et al. (2021), this research places greater emphasis on dynamics. Entrepreneurial dynamic capability is defined as entrepreneurs’ ability to turn resources into goals, including three aspects: the ability to identify and use opportunities (ECC), the ability to innovate (ECI), and the ability to absorb and use external information (ECB). Entrepreneurial dynamic capability is a common outcome variable in dual-path transformation. The capabilities of opportunity identification and innovative behaviors are improved through the direct role of resource integration and entrepreneurial learning. The ability to absorb and apply external information is strengthened by the empowerment of social networks. Eventually, the comprehensive improvement of entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities is jointly promoted.

Entrepreneurial learning (EL). Scholars have discussed and researched entrepreneurial learning and defined it based on the perspectives of relationships, abilities, behaviors, and processes. Although there are differing opinions regarding the definition, there is consensus that entrepreneurs can continuously acquire new knowledge and improve their innovation capabilities through it. Drawing from the research of Hu et al. (2017), we divide the forms of entrepreneurial learning into exploratory learning (ELE) and cognitive learning (ELC). Exploratory learning emphasizes improving innovation by transforming one’s own and others’ experiences in the network into knowledge. This is a transformation of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. Cognitive learning emphasizes improving innovation ability through knowledge acquisition. This represents a transfer from explicit knowledge to explicit knowledge. Zarei et al. (2019) defines the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge as an ongoing process of acquiring and updating knowledge. It is a process of acquiring knowledge through the conversion of experiences, the essence of which is the experience. Furthermore, following Bandera et al. (2018), we define the transformation and dissemination of tacit knowledge into tacit knowledge as experiential learning (ELU). Entrepreneurial learning is a key mediator. It serves as a direct transformation link following resource integration, with experiential learning playing a leading role. Entrepreneurial learning results from the joint interaction of social networks and resource integration, evolving from exploratory to cognitive learning, which reflects varying depths of knowledge transformation.

Resource Integration (RI). The integration of resources is primarily the transmission and improvement of information in entrepreneurial social networks. First, information regarding the supply and demand of products in the market can be obtained through social networks to seize business opportunities. Second, by improving the transmission of information, more symmetrical information can be obtained to reduce losses caused by decision-making errors. Third, capital support for venture investment can be obtained through social networks, laying the foundation for technological innovation. Based on the research of Bruce et al. (2019), we define resource integration based on entrepreneurial social networks as the ability of entrepreneurs to improve the transfer of information (RII), reduce decision-making risks from information asymmetry (RIR), and collect experiences and provide feedback (RIF) through the social networks. Resource integration plays a dual role in this regard. It serves as a core initial element, directly addressing entrepreneurial failure experiences and promoting entrepreneurial learning. It acts as a downstream variable of social networks, receiving and utilizing the experience and resources transmitted through networks. Its functional realization depends on the structure and quality of the social networks.

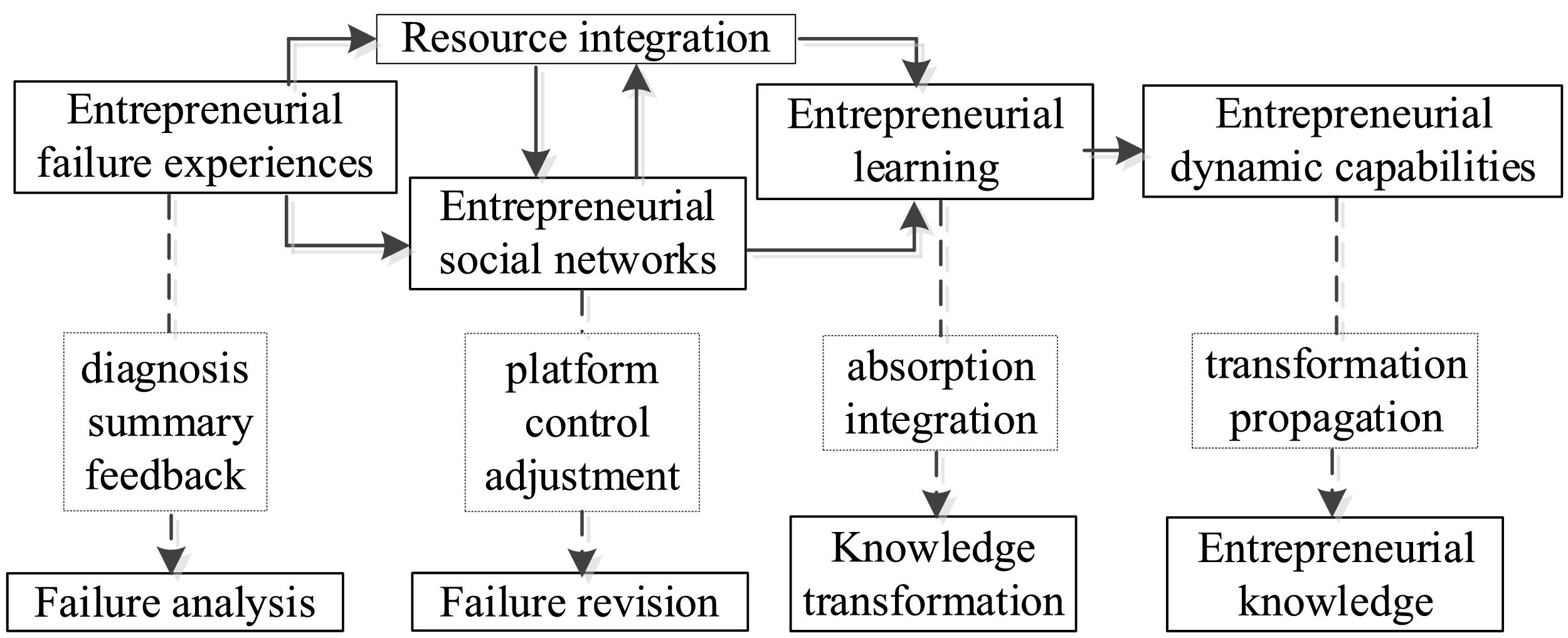

Theoretical analysis and hypothesisBased on the SECI knowledge conversion model (Allal-Chérif & Makhlouf, 2016) and double-loop learning model (Christopher et al., 2016), this study focuses on the conversion logic of entrepreneurial failure experience into entrepreneurial knowledge. From the dual perspectives of knowledge conversion stages and analytical levels, a three-level conversion path framework of "individual - organizational - systemic" is constructed to analyze the mediating mechanisms of social networks and resource integration across different levels and reveal the differences in the dominant learning modes at each level, as depicted in Fig. 1.

The path and mechanism of transforming the entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the individual level.

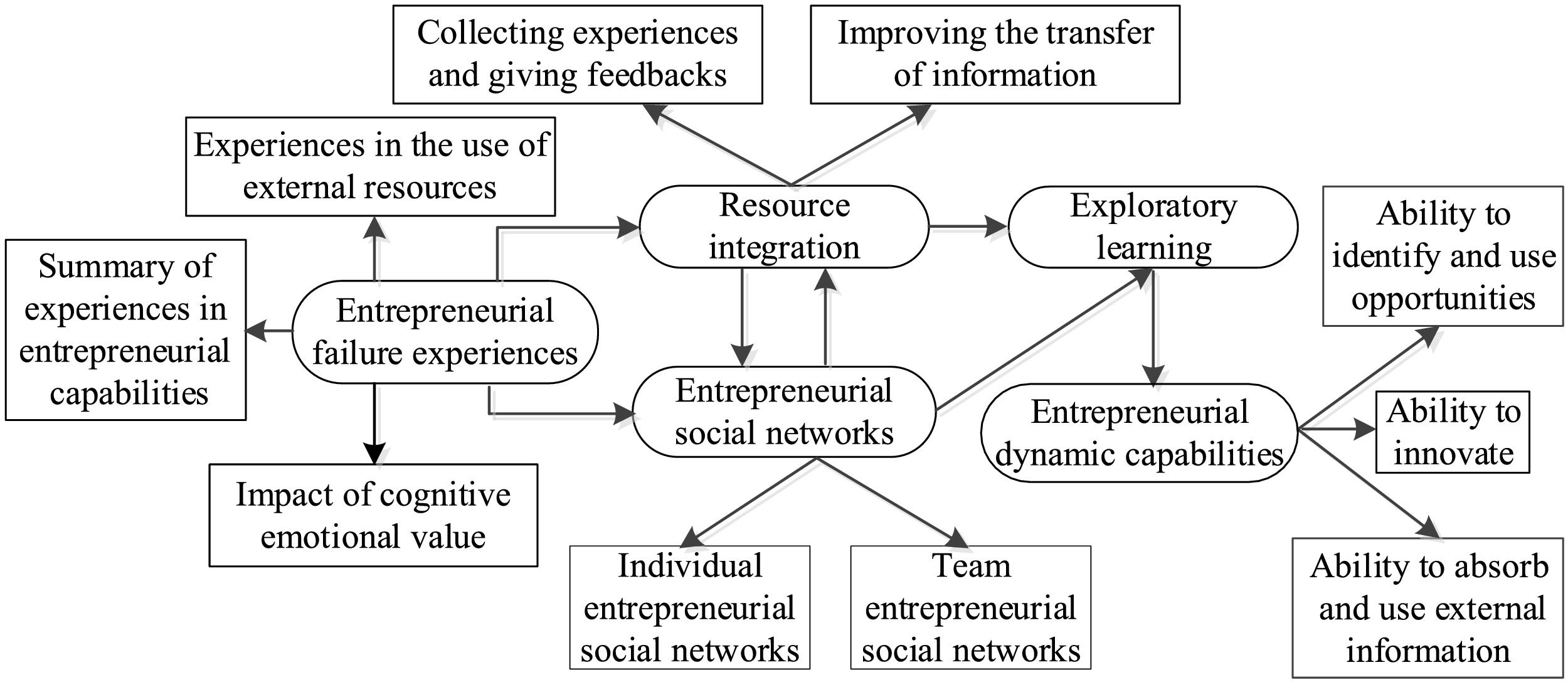

The transformation of entrepreneurial failure experience at the individual level corresponds to the “socialization” process in the SECI model, whose core feature is the direct transfer and internalization of tacit knowledge among individuals (Rui et al., 2018). Entrepreneurial failure experiences often contain many tacit components that are difficult to code. Such knowledge cannot be transmitted through written words or standardized processes and relies on in-depth interaction and situational resonance between individuals. From the perspective of transformation mechanisms, individual entrepreneurial social networks play a fundamental role at this stage. They are primarily composed of entrepreneurs' relatives and friends, former colleagues, and industry partners, and are characterized by strong ties (Waheed et al., 2016). Their interaction scenarios primarily include informal communications (such as tea talks, industry salons, and experience sharing sessions). Entrepreneurs are more willing to disclose details of their failure experiences (the psychological process of decision-making errors, emotional fluctuations in crisis handling), while recipients internalize others' failure experiences into their tacit knowledge through empathy and imitation. Through resource integration, entrepreneurs screen key information from massive failure experiences based on their cognitive frameworks, endow new meanings to such information through interaction with other individuals in the social network, integrate fragmented experiences into structured knowledge modules, and store them in their personal cognitive systems to provide tacit guidance for re-entrepreneurial decisions. In terms of learning mode, this process is dominated by experiential learning. Through the cycle of “experiencing failure → communicating and reflecting with network members → refining failure rules → adjusting re-entrepreneurial behaviors,” entrepreneurs can not only understand the superficial causes of failure (single-loop learning), but also reflect on the defects in their own cognitive frameworks and decision-making logic (double-loop learning), thereby achieving a qualitative improvement in tacit knowledge. This transformation path mechanism from entrepreneurial failure experience to entrepreneurial knowledge at the individual level is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Hypothesis 1 At the individual level, the positive impact of individual entrepreneurial social networks on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experience is stronger than that of team entrepreneurial social networks, with experiential learning serving as the primary learning model.

The path and mechanism of transforming the entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the organizational level.

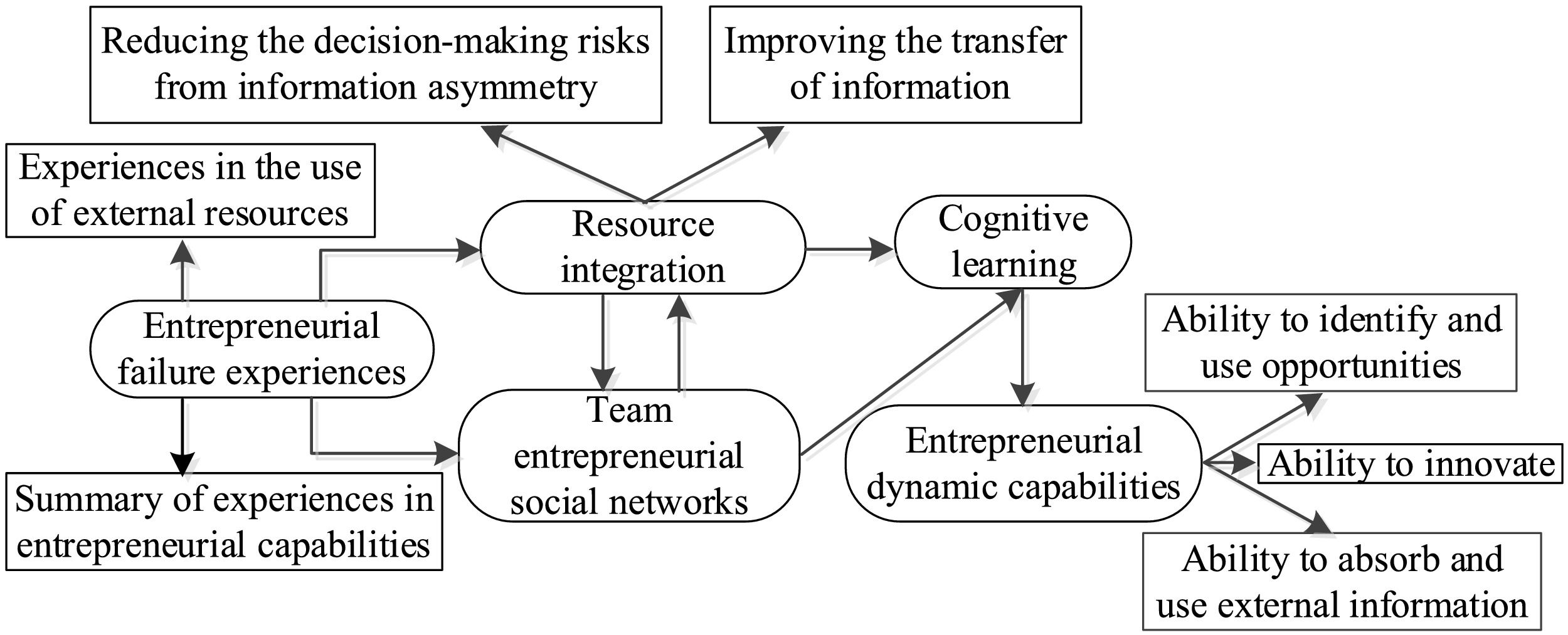

The transformation at the organizational level corresponds to the “externalization” stage of the SECI model, whose core task is to convert the tacit failure experience scattered among individuals into explicit knowledge that can be shared within the organization (Yin et al., 2020). New ventures can obtain resources from the external market through market mechanisms to a certain extent. However, it is difficult to obtain certain resources that determine the competitiveness and growth value of an enterprise. From the transformation mechanism’s perspective, team social networks are important channels and methods for enterprises to form strategic alliances, obtain, and allocate resources. Overall, social networks have a positive impact on enterprise performance. Through formal communication mechanisms, different individuals' tacit failure experiences are collected and aggregated at the organizational level. Additionally, team networks can promote the transfer of cross-domain knowledge and lay a foundation for subsequent resource integration. Personal entrepreneurial social networks continue to play a supplementary role (Trubnikov, 2021). Industry failure cases obtained by individuals through external social relations can serve as a reference for internal experiences, thereby improving the universality of organizational knowledge. Through resource integration, tacit experiences are converted into explicit texts by standardized coding rules (such as failure case reports and operation guides), and this explicit knowledge is embedded into organizational systems to ensure its stable transmission within the organization. In terms of the learning mode, this process is centered on exploratory learning (Silvia et al., 2020). Organizations not only analyze the specific causes of failure but also reflect on the in-depth organizational problems that lead to failure, realizing a systematic upgrade of knowledge transformation. The transformation path mechanism from entrepreneurial failure experience to entrepreneurial knowledge at the organizational level is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Hypothesis 2 At the organizational level, both individual and team entrepreneurial social networks significantly impact the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experience into entrepreneurial knowledge, with exploratory learning as the primary learning model.

The path and mechanism of transforming the entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the systemic level.

The transformation at the systemic level corresponds to the "combination" stage in the SECI model, whose core goal is to integrate scattered organizational explicit knowledge into a systematic knowledge system applicable across organizations (Wei, 2022). The failure experiences accumulated by a single enterprise are often restricted by various factors, such as its industry scenario and resource endowment, hindering the formation of broadly applicable insights. However, through the transformation process at the systemic level, these limitations are broken, and universally applicable entrepreneurial knowledge is formed. From the perspective of transformation mechanisms, the team entrepreneurial social network presents a multi-level structural form of “cross-organizational alliance–knowledge sharing platform–industry standard formulation.” Through a normalized knowledge-sharing mechanism, such as jointly constructing industry failure databases and regularly holding joint review meetings, the flow and integration of knowledge are promoted across a broader scope. In contrast, owing to its relatively limited coverage, the individual entrepreneurial social network provides insufficient support for large-scale cross-organizational knowledge integration. Therefore, its role in the transformation at the systemic level is weaker than that of the team entrepreneurial social network (Cahn et al., 2021). Through resource integration, the team social network collects a wide range of explicit failure knowledge from different organizations and uses advanced technical means, such as big data analysis, to explore the internal connections between various types of knowledge and construct a systematic knowledge system covering the entire entrepreneurial process. This system not only provides solid knowledge support for the entire entrepreneurial ecosystem but also provides effective references for various entrepreneurial subjects in decision-making, execution, and other links. In terms of the learning mode, this process is dominated by cognitive learning (Wang & Shi, 2019), emphasizing the structured reorganization of explicit knowledge. The completeness and accuracy of knowledge are continuously improved through operations such as classification, sorting, and correlation analysis of knowledge. Notably, through in-depth integration and reorganization, the underlying principles behind entrepreneurial failure can be uncovered, providing a macro-level observation perspective for double-loop learning. This helps various actors within the entrepreneurial ecosystem to understand failure and extract lessons from a broader viewpoint, thereby improving the ability of the entire entrepreneurial field to manage risks and avoid failures. The transformation path mechanism from entrepreneurial failure experience into entrepreneurial knowledge at the systemic level is depicted in Fig. 4.

Hypothesis 3 At the systemic level, the role of team entrepreneurial social networks is greater than that of personal entrepreneurial social networks, with cognitive learning as the primary learning model.

Hypothesis 4 In the process of transforming entrepreneurial failure experience into entrepreneurial knowledge, both entrepreneurial social networks and resource integration play mediating roles at the individual, organizational, and systemic levels.

Based on the above analysis of the paths and mechanisms of transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the individual, organizational, and systemic levels, we develop a conceptual model illustrating the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experience into entrepreneurial knowledge, as depicted in Fig. 5.

Research designQuestionnaire designThe questionnaire is designed based on established scales, China’s entrepreneurial context, and the specific objectives of this study. It comprises seven parts: the basic information of entrepreneurs, individual entrepreneurial social networks, team entrepreneurial social networks, entrepreneurial failure experiences, entrepreneurial learning, resource integration, and entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities. All relevant variables are measured using a 7-point Likert scale. The specific information is as follows.

Individual entrepreneurial social network: Based on Rui et al. (2018) scale, it includes 12 items across four dimensions (social network size, social network density, social network heterogeneity, and social network tie strength). Team entrepreneurial social network: Based on Cahn et al.’s 2021’s operational definition, it consists of nine items across three dimensions (intra-team network, inter-team external network, and cross-team network). Entrepreneurial failure experience: Integrating Sarasvathy et al.’s (2013) three-dimensional scale (experience in utilizing external resources, summary of entrepreneurial ability experience, and influence of cognitive and emotional value), nine items were incorporated. An additional two items are included to reflect the unique policy adaptation experience of Chinese entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurial dynamic capability: Drawing on Wang and Zajac’s (2007) scale, this study adjusts the measurement to nine items across three dimensions (ability to identify and utilize opportunities, ability to engage in innovative behaviors, and ability to absorb and apply external information). Entrepreneurial learning: Drawing on the research of Chandler and Lyon (2009), this study includes nine items across three dimensions (experiential learning, exploratory learning, and cognitive learning). According to double-loop learning theory, items related to reflecting on one's own decision-making logic are supplemented, such as “After failure, I will re-examine my entrepreneurial thinking mode.” Resource integration: Based on Wiklund’s (2009) scale, the study includes nine items across three dimensions (collection and feedback of experience, reduction of decision-making risks, and improvement of information transmission). Considering China’s entrepreneurial information environment, an item on “policy information integration” is included, such as “I will integrate entrepreneurial support policy information from different channels.”

Data collection and processingThe samples analyzed in this study consist of entrepreneurs who have established new ventures following prior entrepreneurial failure. We strictly defined and applied the screening criteria for the subsequent new venture after failure according to the research of. From January to June 2024, we organized a research team based at the Tianjin University Youth Entrepreneurship Base to distribute questionnaires in five cities: Tianjin, Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou. A total of 2000 questionnaires were distributed, 1920 questionnaires were retrieved, of which 1660 were deemed valid. The effective response rate was 83.0 %. The survey covered eight main industries.

The research sample comprises re-entrepreneurs who have experienced entrepreneurial failure. (1) Definition of entrepreneurial failure. With reference to Cardon et al.’s (2011) multi-dimensional definition combined with the characteristics of China’s entrepreneurial practice, entrepreneurial failure is operationalized as an entrepreneurial termination event that meets any of the following conditions: ① The enterprise is legally liquidated and its business license is revoked owing to continuous losses or insolvency; ② The entrepreneur takes the initiative to terminate operations and acknowledges that the expected goals have not been achieved; ③ The control of the enterprise is transferred and the new owner does not continue the original business direction. Involuntary terminations caused by force majeure (such as natural disasters, sudden policy changes) are excluded to focus on failure cases from which lessons can be drawn. (2) Constituent elements of a new enterprise. With reference to Sarasvathy et al.’s (2013) definition of entrepreneurship, a new enterprise must simultaneously meet the following conditions: ① It has completed industrial and commercial registration and has the qualification of an independent legal person or individual operation; ② It has a clear product/service positioning and target market; ③ It has carried out actual business activities (such as generating revenue, employing employees); ④ It has no direct connection to the previously failed venture in terms of legal entity and equity structure (excluding reorganization or renaming of the same enterprise). (3) Time range of failure events. Combined with the entrepreneurial learning cycle theory (Rui et al., 2018), the interval between the failure event and the launch of the new venture is set at six months to three years. Samples with an interval shorter than six months are excluded because entrepreneurs may not have completed the reflection and integration of failure experiences; samples with an interval longer than three years are also excluded because excessive time may lead to the attenuation of failure experiences or the introduction of confounding factors (such as drastic changes in the industry environment).

The stratified purposive sampling method was adopted, with the following specific implementation steps. Determination of the sampling frame: Relying on the national entrepreneurship incubation network resources of the Youth Entrepreneurship Base of Tianjin University, the target group comprised re-entrepreneurs in five cities with high entrepreneurial activity, namely Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Tianjin. Their entrepreneurial ecosystems are well-developed, covering different industry types, and their entrepreneurial failure cases are typical. This reduces the impact of regional differences in the research results. Entrepreneur identification process: Eligible re-entrepreneurs were identified through three channels: ① Enterprise files from the entrepreneurship base (accounting for 42 %), were screened with particular attention to the "founder's past entrepreneurial experience" column in the enterprise registration information; ② Recommendation by industry associations (accounting for 31 %), included verified lists of re-entrepreneurs with failure experiences; ③Snowball recommendation (accounting for 27 %), identified re-entrepreneurs and recommended peers in their industry with similar experiences. Duplicate samples were excluded through cross-validation. Recruitment and questionnaire distribution: A combination of "online + offline" methods was used. Offline, questionnaires were distributed on-site at special salons and failure experience sharing sessions organized by the entrepreneurship base (accounting for 65 %), and the survey team provided on-site guidance to respondents to ensure the accuracy of the information. Online, electronic questionnaires with unique identification codes were distributed through entrepreneurial communities (such as Chuangye Bang and 36 Kr entrepreneurial communities) (accounting for 35 %). IP address restrictions were adopted to avoid duplicate filling. All respondents were informed of the research purpose, data usage, and anonymous processing principles, and random red envelopes were used to increase participation rates. The survey was conducted from January to June 2024, with 2000 questionnaires distributed and 1920 successfully recovered. After validity testing (invalid samples—such as those with excessively short filling time and regular answers—were eliminated), 1660 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective recovery rate of 83.0%. Table 1 describes the distribution of sample characteristics, demonstrating that the sample distribution is relatively extensive and representative.

The description statistics of the samples.

(1) Reliability and validity test

SPSS 20.0 is used to test the reliability and validity of the data. The results are depicted in Table 2. All Cronbach’s alpha values are greater than 0.7, indicating high reliability across all questionnaire items. Confirmatory factor analysis is adopted to test validity. All KMO values are higher than 0.7. Moreover, the values of Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity near 0.000, confirming that the questionnaire exhibits good construct validity. Furthermore, the results of the AVE test present that the AVE values of all variables exceed 0.5, indicating that the questionnaire exhibits good discriminant validity.

The results of reliability and validity test.

The correlation coefficients of the variables are depicted in Table 3. Significant correlations exist between the potential variables at a highly significant level. Significant correlations exist between entrepreneurial failure experiences, individual and team entrepreneurial social networks, resource integration, entrepreneurial learning, and entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities. Significant correlations exist between entrepreneurial failure experience, resource integration, and entrepreneurial learning. Significant correlations exist between individual and team entrepreneurial social networks and entrepreneurial learning. Additionally, significant correlations exist between entrepreneurial learning and entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities. This suggests that resource integration, individual entrepreneurial social networks, and team entrepreneurial social networks play intermediary roles in the process of transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge.

The correlation coefficients between variables.

Note: *, **, and *** denote a confidence level of 1 %, 5 %, and 10 %, respectively.

Test of the mediator effect. According to Cahn et al. (2021) method of testing the mediator effect, we use Stata 14.0 software to perform the following regression analyses: entrepreneurial failure experiences and entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities (Model 2), entrepreneurial failure experiences, resource integration, and entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities (Model 3), entrepreneurial failure experiences, entrepreneurial social networks, and entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities (Model 4), entrepreneurial failure experiences, resource integration, entrepreneurial learning, and entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities (Model 5), entrepreneurial failure experiences, entrepreneurial social networks, entrepreneurial learning, and entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities (Model 6), and entrepreneurial failure experiences, entrepreneurial social networks, entrepreneurial learning, resource integration, and entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities (Model 7). The results are presented in Table 4.

The results of multiple linear regression.

Note: *, **, and *** denote a confidence level of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

Test of the transformation path and mechanism. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is a multivariate statistical method for analyzing the relationships between variables based on the covariance matrix of the variables. It does not have strict assumptions and constraints and can be used to analyze abstract concepts. It can estimate the latent variables and regress the entire model simultaneously. SEM can solve the problems of multicollinearity and describe the latent variables. It is widely used in the fields of healthcare, social issues, economic development, management, and education (Tihomir & Bengt, 2016). In this study, from the perspective of the mediating effect of entrepreneurial social networks, we use the SEM model to test the path and mechanism of transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge. The SEM model used in this study is depicted in Fig. 6. Additionally, it is estimated using AMOS 20.0. According to the estimation results in Table 5, χ2/df=0.162<3, both NNFI (0.921) and CFI (0.924) are greater than 0.9, the PNFI (0.645) is greater than 0.5, and RMSEA (0.03) is less than 0.1, indicating that the estimation results are robust.

Estimation of the SEM model.

Note: ω represents the contribution degree of the secondary index; “→” represents the effect direction.

(1) The mediator effect of resource integration

According to the results of Model 2 in Table 4, entrepreneurial failure experiences have a significant positive effect on entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities, and the transformation of summarized experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge is the greatest (0.352). Upon including resource integration in Model 3, resource integration has a significant positive promotion effect on entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities. However, there are decreases in the transformation degrees of the experiences in the use of external resources, the summary of experiences in entrepreneurial capabilities, and the impact of cognitive emotional value on the entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities, respectively (0.305 → 0.236, 0.352 → 0.301, 0.343 → 0.246). Therefore, resource integration has a mediating effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge.

After including entrepreneurial learning in Model 5, there was a decrease in the degree of the effect of resource integration. The effects of reducing decision-making risks from information asymmetry, collecting experiences, giving feedbacks, and improving the transfer of information decrease to 0.311, 0.403, and 0.241 from 0.365, 0.486, and 0.263, respectively. Therefore, entrepreneurial learning mediates the relationship between resource integration and entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities. This further tests Path 1 of transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge: entrepreneurial failure experiences → resource integration →entrepreneurial learning → entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities.

(2) The mediator effect of entrepreneurial social networks

After including entrepreneurial social networks in Model 4, entrepreneurial social networks have a significant positive effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge. Additionally, there are decreases in the effect degrees of experiences in the use of external resources, summary of experiences in entrepreneurial capabilities, and impact of cognitive emotional value, respectively (0.305 → 0.257, 0.352 → 0.306, 0.343 → 0.259). Therefore, entrepreneurial social networks have a mediating effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge.

After including entrepreneurial learning in Model 6, there is a decrease in the effect degree of entrepreneurial social networks (0.469 → 0.396). Therefore, entrepreneurial learning has a mediating effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial social networks into entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities. After including resource integration in Model 7, comparing the results of Models 5 and 7, the effects of reducing decision-making risk from information asymmetry, collecting experiences and giving feedbacks and improving the transfer of information decrease to 0.301, 0.335, and 0.213 from 0.311, 0.403, and 0.241, respectively. Therefore, resource integration has a mediating effect on the relationship between entrepreneurial failure experience and entrepreneurial social networks. This further tests Path 2 of transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge: entrepreneurial failure experiences → entrepreneurial social networks → resource integration →entrepreneurial learning → entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities.

Test and discussion of the path and mechanism of transforming the entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge

(1) At the individual level

According to Khelil (2016), the magnitude of entrepreneurial failure costs has a significant impact on subsequent new ventures after failure, especially on entrepreneurial orientation. The dissemination of entrepreneurial failure experiences at the individual level is primarily based on word-of-mouth sharing, which is the transfer of tacit knowledge to tacit knowledge. According to the results of paths 1 and 2 in Table 5, in the transformation mechanism of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge, the effect of collecting experiences and giving feedback on resource integration is the greatest (0.42). The process of knowledge transformation primarily transforms the impact of cognitive emotional value into the ability to identify and use opportunities (0.43) using the experiential learning mode (0.53) through individual entrepreneurial social networks (0.68).

(2) At the organizational level

According to Lee et al. ’s (2015) organizational behavior theory, the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge determines the fate of new firms after failure. Social networks, as an important factor influencing the decision-making of firms, largely determine the performance of the subsequent venture after failure, especially the conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge at the organizational level for transmission and sharing. According to the results of paths 1 and 2 in Table 5, in the transformation process of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the organizational level, the effect of reducing decision-making risks from information asymmetry of resource integration is the greatest (0.39). The process of knowledge transformation is primarily to transform the experiences in the use of external resources into the ability to absorb and use external information (0.45) using the exploratory learning mode (0.45) through the individual and team entrepreneurial social networks (0.51, 0.49).

(3) At the systemic level

According to the entrepreneurial learning theory of Marge et al. (2016), the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the systemic level is the dissemination and sharing of explicit knowledge. New firms can acquire resources (opportunities to create a new venture, financial support, etc.) and promote entrepreneurial learning to improve their entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities through social networks. According to the results of paths 1 and 2 in Table 5, in the transformation process of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the systemic level, the effect of improving the transfer of information on resource integration is the greatest (0.42). The process of knowledge transformation primarily transforms accumulated experiences in entrepreneurial capabilities into the ability to innovate (0.45) using the cognitive learning mode (0.56) through the team entrepreneurial social networks (0.65).

Robustness analysisSince all the data are obtained from questionnaire surveys, and there is currently no professional statistical company that conducts long-term tracking statistics, the robustness is tested by replacing the explained variable, the core explanatory variable, and excluding specific samples, based on the previous variable settings and empirical experience. Regarding the variable replacement methods, Passavanti et al. (2025) observed that there are three common construction methods: using the industry average, regional average, and one-period lag of the variable as instrumental variables. Cahn et al. (2021) used the statistical results obtained by reducing the number of words in the indicator’s lexicon as the instrumental variable. Ioanna et al. (2019) conducted robustness tests by excluding certain specific samples.

Drawing on the above practices, this study employed the following three variable substitution methods: The original variable was replaced with the average value across five regions. The original variable was re-estimated using the first two items, as their factor loadings together explained 70% of the variance. Based on the original five regions, the survey scope was expanded to include 178 national high-tech development zones in China for data collection, as these zones—supported by various policies such as tax reductions, exemptions, and financial subsidies—serve as key hubs for entrepreneurial activity.

Based on the above three variable replacement methods, the SEM model is re-estimated, and the results are depicted in Table 6. The results in Table 6 are consistent with those in Table 5, confirming the robustness of the SEM model estimation results.

Robustness tests.

Note: The symbol "→" indicates the direction of influence.

The transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge varies across different types of entrepreneurships. Drawing from Steffen et al.’s (2014) research, according to the entrepreneur’s risk preference and the entrepreneurial intention, we divide the entrepreneurship into three types: the adventure type, the venture investment fusion type and the revolutionary type. For adventure-type entrepreneurship, the opportunity cost is low, technological progress is the core competitiveness, and business opportunities in the market are the main focus. Adventurous entrepreneurs focus more on market opportunities; therefore, the key to their knowledge transformation lies in how they promote resource integration and respond quickly. For the venture investment fusion type of entrepreneurship, there are high-standard management teams, clear target markets and plans, and products and technologies are the main focus. Venture investment fusion startups require substantial capital to achieve market penetration and iterative updates; therefore, they place greater emphasis on iterative technology development and investment in the process of knowledge transformation. Revolutionary entrepreneurship generates the most effective entrepreneurial plans, as well as the greatest wealth and value. Products and services with excess value are provided to customers through innovation in production technology and management processes. Revolutionary entrepreneurs focus more on unprecedented innovation, experience, and application; therefore, they place greater emphasis on exploratory knowledge transformation and attach more importance to cognitive learning in the knowledge transformation process. We analyze the characteristics of the transformation mechanism of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge for different types of entrepreneurships, and the results are depicted in Table 7.

Estimation of the transformation mechanisms for different types of entrepreneurships.

Note: *, **, and *** denote a confidence level of 1 %, 5 %, and 10 %, respectively.

First from the estimation results of the adventure type in Table 7, it can be observed that the impact of cognitive emotional value (0.453) of entrepreneurial failure experiences transforms into entrepreneurial knowledge. Second, adventurous entrepreneurs pay attention to the use of low-cost opportunities, and the sources of investment are small. The effect of individual entrepreneurial social networks is higher than that of team entrepreneurial social networks (0.542> 0.458). Third, collecting experiences and providing feedback has the greatest mediating effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge (0.342). Fourth, in the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge, experiential learning is the main entrepreneurial learning mode (0.452). After the transformation, the ability to absorb and use external information is improved. For example, many testing companies and mask manufacturers established during the COVID-19 pandemic achieved entrepreneurial success mainly through capabilities such as resource integration and rapid change. This is consistent with the conclusions of this study.

According to the estimation results of the venture investment fusion type in Table 7, first, it is primarily the experience related to the use of external resources (0.532) of entrepreneurial failure experiences that transforms into entrepreneurial knowledge. Second, entrepreneurs of the venture investment fusion type focus on efficient teamwork. They provide technologies and products with excessive value under clear market goals. That is, the effect of team entrepreneurial social networks is greater than that of individual entrepreneurial social networks (0.537 > 0.463). Third, reducing decision-making risks from information asymmetry has the greatest mediating effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge (0.451). Fourth, in the transformation process of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge, exploratory learning is the main entrepreneurial learning mode (0.386). After the transformation, the ability to identify and use opportunities is improved. For example, China's Unitree Robotics has enhanced its R&D capabilities by building up previous accumulations and securing external venture capital, enabling it to better transform the experience of failures into knowledge for subsequent experimental development, thereby achieving iterative updates.

According to the estimation results of the revolutionary type in Table 7, first, it is primarily the accumulation of experiences in entrepreneurial capabilities (0.486) of entrepreneurial failure experiences that transforms into entrepreneurial knowledge. Second, revolutionary entrepreneurs focus on optimal technological transformation and rely on technological innovation capabilities and innovative management strategies. The effect of team entrepreneurial social networks is greater than that of individual entrepreneurial social networks (0.645 > 0.355). Third, improving the transfer of information has the greatest mediating effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge (0.417). Fourth, in the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge, cognitive learning is the main entrepreneurial learning mode (0.559). Following the transformation, the ability to innovate is improved. For example, DeepSeek is a typical revolutionary startup. The open-source model DeepSeek-R1 released by the company demonstrates performance comparable to that of GPT-3.5 in key fields such as mathematics and programming, while its cost is significantly lower. Originally a quantitative analysis firm, the company’s success hinges on its accumulated experience, especially the transformation of exploratory knowledge.

Path and mechanism of transforming the entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge for different entrepreneurial fieldsAccording to action theory, entrepreneurship is a process of identifying opportunities, evaluating them, and leveraging them to integrate resources to create and realize potential value, thereby generating business profits. In the process of starting a business, industry selection significantly impacts entrepreneurial activities, and different industry choices lead to distinct entrepreneurial characteristics. Further comparison of the research on entrepreneurial failure learning by Cope and Schutjens reveals that the learning content from first-time entrepreneurial failure can be divided into three dimensions: self-learning, internal learning, and external learning. Self-learning refers to entrepreneurs’ discovery or recognition of their own strengths and weaknesses, entrepreneurial motivations and goals, and role transitions after their first venture failure. Internal learning denotes the entrepreneurial knowledge acquired by entrepreneurs regarding the establishment, management, and closure of new ventures, gained through their experience in all stages of founding, owning, and closing a new enterprise. External learning refers to the new external network relationships developed and new business opportunities identified by entrepreneurs through their entrepreneurial activities. Novice entrepreneurs of different types vary greatly in terms of the content they learn from entrepreneurial failure experiences. These differences have two impacts on novice entrepreneurs: first, they affect the speed at which they recover from entrepreneurial failure; second, they influence their career orientation following failure. Specifically, whether an entrepreneur chooses to continue entrepreneurship largely depends on the differences in entrepreneurial learning content.

We investigated eight industries. According to Rajarishi (2019), we classified the eight industries into three categories: high-tech (consulting services, e-commerce, and software), shopkeepers (catering, leasing, and retail trade), and processing and manufacturing fields. We analyzed the characteristics of the transformation mechanism of entrepreneurial failure experience into entrepreneurial knowledge for different entrepreneurial fields, and the results are presented in Table 8.

Estimation of the transformation mechanisms for different entrepreneurial fields.

Note: *, **, and *** denote a confidence level of 1 %, 5 %, and 10 %, respectively.

The estimation results for the high-tech field in Table 8 illustrates that the summary of experiences in entrepreneurial capabilities (0.514) of entrepreneurial failure experiences transforms into entrepreneurial knowledge. Second, the effect of team entrepreneurial social networks is higher than that of individual entrepreneurial social networks (0.645 > 0.355) in the high-tech field. Third, improving the transfer of information has the greatest mediating effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge (0.415). Fourth, in the transformation process of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge, cognitive learning is the primary entrepreneurial learning mode (0.387). Following the transformation, the ability to innovate is improved.

According to the estimation results of the shopkeepers’ field in Table 8, first, the impact of cognitive emotional value (0.453) of entrepreneurial failure experiences transforms into entrepreneurial knowledge. Second, firms in the shopkeepers’ field acquire resources and information primarily through individual entrepreneurial social networks, which could reduce management costs and enable the identification of business opportunities. The effect of individual entrepreneurial social networks is greater than that of team entrepreneurial social networks (0.732 > 0.268). Third, collecting experiences and providing feedback has the greatest mediating effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge (0.398). Fourth, in the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge, experiential learning is the primary entrepreneurial learning mode (0.412). After the transformation, the ability to absorb and use external information is improved.

According to the estimation results of the processing and manufacturing field, first, the summary of experiences in entrepreneurial capabilities (0.526) of entrepreneurial failure experiences transforms into entrepreneurial knowledge. Second, the key point for firms in the processing and manufacturing field is exploitative learning through individual entrepreneurial social networks, thereby improving the firms’ ability to seize business opportunities and improving the performance of subsequent new ventures. The effect of team entrepreneurial social networks is greater than that of individual entrepreneurial social networks (0.526 > 0.474). Third, collecting experiences and providing feedback has the greatest mediating effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge (0.417). Fourth, in the transformation process of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge, exploratory learning is the primary entrepreneurial learning mode (0.346). Following the transformation, the ability to identify and use opportunities is improved.

Overall, the content that novice entrepreneurs learn from entrepreneurial failure varies significantly depending on the industry in which they are, which is consistent with previous research. Belas et al. (2025) found that high-tech entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs in traditional industries differ significantly in their priority ranking of learning content. Moreover, high-tech entrepreneurs have a stronger growth orientation, and their priority learning areas, ranked by importance, include decision-making, financing, business value enhancement, motivation, and success skills in a rapidly changing environment. This aligns with the conclusions of this study. In the manufacturing industry, the proportion of survival-driven entrepreneurship is higher than that of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. Therefore, the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge in this sector is mainly derived from resource integration and the identification of opportunities.

Path and mechanism of transforming the entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge under different entrepreneurial failure costsEntrepreneurial failure has the characteristics of discreteness, fragmentation, and diversity (Nuray, 2016), which directly affects the willingness to start a new venture after failure and thus indirectly affects the transformation mechanism of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge. The cost of entrepreneurial failure includes economic and psychological costs. The economic cost can be repaired with the help of external support, but the psychological cost must be repaired by the entrepreneurs themselves. The degree of repair has a significant impact on the transformation of entrepreneurial knowledge. First, economic cost is a direct consequence of entrepreneurial failure. The economic cost of entrepreneurial failure can affect subsequent entrepreneurial intentions. When the economic cost of failure is excessively high, entrepreneurs are often unable to bear the heavy financial pressure and thus lack the capacity to continue their entrepreneurial endeavors. Second, entrepreneurial failure not only brings economic losses to entrepreneurs but also exerts a certain impact on their personal connections, social circles, and social status. Particularly, after bearing substantial social costs, entrepreneurs may be forced to withdraw from their original social networks and struggle to obtain external material support from other social networks. The loss of social resources further reduces the intention to re-engage in entrepreneurship. Third, the emotional cost of entrepreneurial failure is a factor that cannot be ignored. Entrepreneurs who experience failure may be trapped in negative emotions such as inferiority, depression, disappointment, and remorse for a long time, which erodes their self-confidence and motivation. These emotional costs may reduce entrepreneurs’ individual self-efficacy and affect the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge. We divide the cost of entrepreneurial failure into high and low failure costs. We analyze the characteristics of the transformation mechanism of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge under high and low failure costs; the results are presented in Table 9.

Estimation of the transformation mechanisms under different entrepreneurial failure costs.

Note: *, **, and *** denote a confidence level of 1 %, 5 %, and 10 %, respectively.

According to the estimation results of the high failure cost in Table 9, first, the impact of cognitive emotional value (0.403) of entrepreneurial failure experience transforms into entrepreneurial knowledge. Second, the impact of high failure costs on failed entrepreneurs is not just economic losses but, more importantly, psychological losses. Economic losses can be reduced by the support of external networks, and psychological losses must be repaired by the entrepreneurs themselves. The effect of individual entrepreneurial social networks is greater than that of team entrepreneurial social networks (0.623 > 0.377). Third, collecting experiences and providing feedback have the greatest mediating effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge (0.356). Fourth, in the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge, both cognitive learning (0.354) and experiential learning (0.356) are the main entrepreneurial learning modes. Following the transformation, the ability to absorb and use external information is improved.

According to the estimation results of low failure cost in Table 9, first, the summary of experiences in entrepreneurial capabilities (0.565) of entrepreneurial failure experiences transforms into entrepreneurial knowledge. Second, under a low failure cost, both economic and psychological losses can be healed quickly. Therefore, enterprises focus on obtaining resources and information through team entrepreneurial social networks and seizing the business opportunities of starting a new venture. Third, both reducing decision-making risks from information asymmetry and improving the transfer of information have the greatest mediating effects on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge (0.353). Fourth, in the transformation process of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge, exploratory learning is the main entrepreneurial learning mode (0.423). Following the transformation, the ability to innovate is improved.

Overall, the higher the cost of entrepreneurial failure, the more profound and unforgettable the experience for entrepreneurs, and the more likely it is to be regarded as a significant failure experience. Specifically, the higher the cost of a failure event, the greater the motivation for learning. Zhang (2025) argues that failure provides entrepreneurs with numerous learning opportunities and can be viewed as a channel for entrepreneurial learning. Financial and social costs positively impact entrepreneurial failure learning. The cost of entrepreneurial failure stimulates entrepreneurs to reflect and triggers their learning, which, in turn, changes their original mental models and strengthens enterprise management. Entrepreneurial failure also promotes the improvement of entrepreneurs’ capabilities in resource and team management, enriches their entrepreneurial experience, and ultimately enhances their entrepreneurial capabilities by learning from such experiences.

Conclusions and research outlookBased on the SECI knowledge transformation model and the double loop learning model, we classified the entrepreneurial social networks into the individual and team entrepreneurial social networks. We analyzed the path and mechanism of transforming the entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at three levels: individual, organizational, and systemic. Further, we analyzed the transformation mechanism of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge for different entrepreneurial types, fields, and failure costs.

- (1)

There are two paths of transforming the entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge. Path 1: entrepreneurial failure experiences → resource integration → entrepreneurial learning → entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities. Path 2: entrepreneurial failure experiences → entrepreneurial social networks → resource integration → entrepreneurial learning → entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities. The transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the individual level primarily represents the transmission from tacit knowledge to tacit knowledge. The mediator effect of individual entrepreneurial social networks is significant, and ultimately entrepreneurs’ ability to identify and use opportunities is improved. The transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the organizational level primarily represents the transmission from tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge. Both the mediator effects of individual and team entrepreneurial social networks are significant, and ultimately entrepreneurs’ ability to absorb and use external information is improved. The transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge at the systemic level primarily represents the transmission and sharing of explicit knowledge to explicit knowledge. The mediator effect of team entrepreneurial social networks is significant, and ultimately entrepreneurs’ ability to innovate is improved.

- (2)

For the adventure type, entrepreneurial failure experiences transform into the entrepreneurial knowledge primarily through the individual entrepreneur networks. The primary learning mode is experiential learning, and the entrepreneurs’ ability to absorb and use external information is improved. Collecting experiences and giving feedbacks has the greatest mediator effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge. For the venture investment fusion type, entrepreneurial failure experiences transform into the entrepreneurial knowledge primarily through the team entrepreneur networks. The primary learning mode is exploratory learning, and the entrepreneurs’ ability to identify and use opportunities is improved. Reducing decision-making risks from information asymmetry has the greatest mediator effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge. For the revolutionary type, entrepreneurial failure experiences transform into the entrepreneurial knowledge primarily through the team entrepreneur networks. The primary learning mode is cognitive learning, and the entrepreneurs’ ability to innovate is improved. Improving the transfer of information has the greatest mediator effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge.

- (3)

For the high-tech field, entrepreneurial failure experiences transform into the entrepreneurial knowledge primarily through the team entrepreneur networks. The primary learning mode is cognitive learning, and the entrepreneurs’ ability to innovate is improved. Improving the transfer of information has the greatest mediator effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge. For the shopkeepers field, entrepreneurial failure experiences transform into the entrepreneurial knowledge primarily through the individual entrepreneur networks. The primary learning mode is experiential learning, and the entrepreneurs’ ability to identify and use opportunities is improved. Collecting experiences and giving feedbacks has the greatest mediator effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge. For the processing and manufacturing field, entrepreneurial failure experiences transform into the entrepreneurial knowledge primarily through the team entrepreneur networks. The primary learning mode is exploitative learning, and the entrepreneurs’ ability of innovate is improved. Collecting experiences and giving feedbacks has the greatest mediator effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge.

- (4)

Under the high failure cost, entrepreneurial failure experiences transform into the entrepreneurial knowledge primarily through the individual entrepreneur networks. The primary learning modes are cognitive and experiential learning modes, and the entrepreneurs’ ability to absorb and use external information is improved. Under the low failure cost, entrepreneurial failure experiences transform into the entrepreneurial knowledge primarily through the individual entrepreneur networks. The primary learning mode is exploratory learning, and the entrepreneurs’ ability of innovate is improved.

The theoretical contributions of this study are reflected in the following aspects. (1) The application scenarios of knowledge conversion and learning theories is expanded. By combining the SECI knowledge conversion model with double-loop learning theory, a three-level transformation framework of entrepreneurial failure experience (individual-organizational-system) is constructed, which reveals the transformation principles from tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge and from individual knowledge to systematic knowledge, providing a new perspective for the application of knowledge management theory in the context of entrepreneurial failure. (2) The understanding of the transformation mechanism is improved. By distinguishing the differentiated roles of individual and team entrepreneurial social networks at different levels, the mediating roles of resource integration and entrepreneurial learning are clarified, making up for the deficiency in existing research that insufficiently explores the process mechanism of how failure experience is transformed into effective knowledge. (3) The contingency role of social networks and resource integration is further refined. This study finds that the intensity of the role of social networks (individual/team) and resource integration changes dynamically with the transformation level (individual networks are more critical at the individual level, and team networks dominate at the systemic level), which supports the situational dependence of social capital theory in the entrepreneurial process. (4) Hierarchical differences in entrepreneurial learning models are revealed. This study clarifies the law that experiential learning is dominant at the individual level, exploratory learning at the organizational level, and cognitive learning at the systemic level, which deepens the understanding of the dynamic process of entrepreneurial learning and provides new evidence for the concrete application of double-loop learning theory.

The findings of this study have the following practical implications for entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial teams, and policymakers: (1) Individual entrepreneurs should prioritize building and maintaining social networks with strong ties (such as relatives, friends, and former colleagues). Through informal communications (such as experience-sharing sessions), they should take the initiative to disclose details of failures and absorb others' experiences and internalize tacit knowledge into their own cognition by means of experiential learning. Meanwhile, they should screen failure-related information based on their own frameworks, reflect on the flaws in their decision-making logic through double-loop learning, and improve the quality of their re-entrepreneurial decisions. (2) For entrepreneurial teams/organizations: Teams should construct a two-layer network of "internal collaboration + external alliance.” They should collect individual failure experiences through formal communication mechanisms (such as regular review meetings) and convert tacit knowledge into explicit organizational knowledge using standardized coding (such as failure case reports). Simultaneously, they should strengthen cross-domain knowledge integration and promote systematic knowledge upgrading at the organizational level through exploratory learning to avoid repeating mistakes. (3) For policymakers and builders of entrepreneurial ecosystems: They should promote the establishment of cross-organizational knowledge-sharing platforms (such as industry failure databases and joint review mechanisms), support leading enterprises, industry associations, and scientific research institutions in forming strategic alliances, and facilitate knowledge integration at the system level. Additionally, they should guide entrepreneurial ecosystems to adopt cognitive learning models, explore the laws of failure through big data analysis, provide macro-level knowledge support for entrepreneurs, and improve the external environment for transforming entrepreneurial failure experiences.

The limitations and research outlook of this study are as follows. First, there is a certain one-sidedness and subjectivity in the selection and measurement of indicators. There are no corresponding established scales for reference for measuring entrepreneurial failure experiences, entrepreneurial dynamic capabilities, and resource integration. The data are obtained primarily through questionnaire surveys based on the existing literature. Future research should focus on developing corresponding scales. Second, this study did not consider the impact of environmental characteristics on the relationships between the variables. Future research should explore the impact of environmental factors on the transformation of entrepreneurial failure experiences into entrepreneurial knowledge. Third, regarding the relationship between entrepreneurial failure learning and subsequent entrepreneurial intentions, future research should conceptualize entrepreneurial failure learning as a system. The overall relationship among its antecedents (cost of entrepreneurial failure) and the consequences (subsequent entrepreneurial intention) should be studied from the perspective of systems theory. In addition, future research should focus on the impact of various components within the learning system (learning process, learning content, learning mode, etc.) and different regulatory factors on subsequent entrepreneurial intentions.