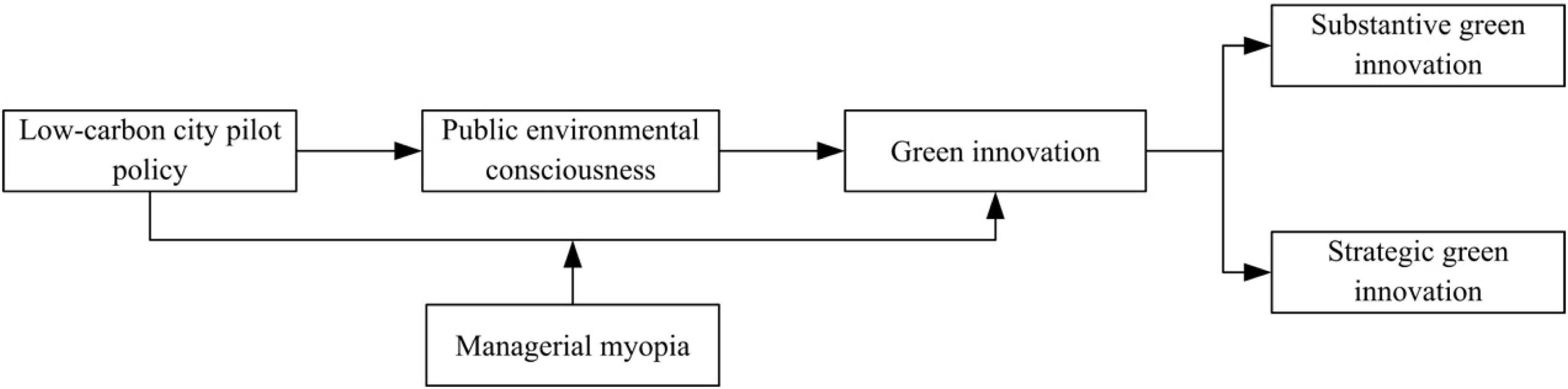

China’s low-carbon city pilot policy (LCCPP) plays a crucial role in reducing carbon pollution and promoting green development. It stimulates enterprises’ green innovation (GI), such as through the promotion of circular carbon technologies and energy-efficient practices. However, a negative trend has emerged, wherein enterprises are increasingly focusing on low-end innovation to secure subsidies or comply with regulatory requirements. Despite this situation, few studies have explored the mechanisms driving enterprises’ adoption of either substantial or superficial GI within the LCCPP framework. This study uses data from Chinese A-share listed companies (2007–2022) and employed a difference-in-differences model to analyze the impact of the LCCPP on GI. Results show that while the LCCPP significantly promotes substantive GI, its effect on strategic GI is minimal. The policy primarily promotes substantive GI by increasing public environmental awareness, with managerial myopia moderating this relationship. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the LCCPP boosts GI in technology-intensive enterprises and those with a high fixed asset ratio. However, it has limited impact on labor-intensive enterprises and those with a low fixed asset ratio. These findings contribute to the existing body of literature on low-carbon pilot policies and offer policy recommendations for enhancing innovation incentives in the context of carbon neutrality.

The ongoing global warming underscores the urgent need to control greenhouse gas emissions from human activities. Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, achieving carbon neutrality and improving energy efficiency have become key global objectives. The agreement aims not only to limit the rise in global temperatures to within 2 °C above pre-industrial levels but also to promote the adoption of circular carbon technologies and resource-conservation practices for pursuing the more ambitious target of 1.5 °C. As a significant emitter, China has proactively assumed responsibility for reducing its carbon footprint. The country has committed to implementing the greenhouse gas emission targets of the Paris Agreement and has launched three rounds of low‑carbon city pilots in 2010, 2012, and 2017 (Wang et al., 2023). >80 cities have been included in the pilot project to date.

The low-carbon city pilot policy (LCCPP) is designed to enhance energy efficiency, accelerate the development of green technologies, optimize the energy mix, and facilitate the transition of cities from high-carbon to low-carbon economies. The LCCPP significantly facilitates the realization of green development and is vital in stimulating green innovation (GI). Each pilot city formulates a low-carbon development plan based on its own characteristics, and enterprises’ GI is encouraged through special fiscal projects, tax incentives, and financial support (Liu et al., 2025; Gürlek & Tuna, 2018). For example, the Aluminum Corporation of China has actively responded to low-carbon pilot policies, restructured its innovation system, overcome a series of technological bottlenecks related to energy conservation and carbon reduction, and continuously enhanced its core competitiveness. In 2022, it reduced carbon emissions by >1.6 million tons, achieving a win–win outcome that combined external GI with internal economic benefits (Sina Finance & Economics, 2022).

GI has been categorized into two forms. Substantive GI focuses on maintaining both competitive advantage and environmental performance and is often considered more technically demanding and innovative. The other type is strategic GI, which seeks to gain benefits and cater to government policies (Li & Zheng, 2016). However, a small number of enterprises choose to pursue low-level innovations with lower complexity and shorter development cycles, motivated by the desire for short-term profit maximization (Hu & Jin, 2021). The strategic GI approach of prioritizing quantity over quality in enterprise innovation is ineffective in reducing pollution and carbon emissions. Instead, it triggers a phenomenon known as the patent bubble (Lin et al., 2021). For instance, China Coal Energy Company Limited has filed an impressive 153 patent applications in 2022, of which 70 have been granted authorization. However, after receiving multiple environmental fines, it has once again appeared on the environmental risk list (Zhang, 2023). To some extent, this phenomenon reflects a GI illusion within Chinese enterprises. This observation prompts reflection on whether Chinese enterprises are strategically responding to the LCCPP through innovative approaches centered on rapid implementation and high output volume or whether they are embarking on substantive GI to improve environmental performance in the context of carbon neutrality.

Currently, the exploration of the innovation compensation effect and the follow-the-cost effect forms the primary basis for studying the GI effects of China’s LCCPP. According to the follow-the-cost effect, LCCPP implementation increases pollution control expenses, consumes R&D funds, and hinders enterprise innovation (Duan & Xu, 2023). From the perspective of the innovation compensation effect, LCCPP implementation encourages enterprises to engage in GI, which enhances competitiveness (Xiong et al., 2020). Further studies have shown that LCCPP implementation primarily boosts GI quantity by providing financial support and strengthening the environmental constraints of the government at the city level (Zhang et al., 2022). However, it also leads to a decrease in innovation quality. Existing research has not reached a consensus on the innovation compensation effect or the follow-the-cost effect of the LCCPP. Given the potential coexistence of both effects, further differentiated research is needed to identify the conditions under which the innovation compensation effect outweighs the follow-the-cost effect. However, this aspect has been rarely explored in existing studies, with only a few studies exploring it from the perspectives of innovation in renewable energy technology and low-carbon technology (Ma & Si, 2022; Yu et al., 2023). In practice, enterprises embedded in specific institutional environments actively adopt strategies and take initiatives to attain legitimacy and access the resources necessary for enterprise development. When institutional pressure is low, enterprises may be motivated to symbolically comply with policies (Luo & Wu, 2023). However, the GI effects of the LCCPP, particularly from the perspective of differences in innovation motivations, have not yet been explored. This study addresses this gap through the first research question (RQ1): Does China’s LCCPP promote substantive GI or strategic GI among enterprises?

Although existing studies have primarily explored the indirect impact of the LCCPP on enterprises’ GI from the perspectives of cost inputs, resource acquisition, and strategic decision making (Xiao et al., 2023), the underlying mechanisms through which the LCCPP affects GI remain underexplored. Stakeholder theory emphasizes that stakeholders, including government, consumers, and investors, affect enterprises’ decision making. Therefore, as the LCCPP elevates public awareness of environmental concerns through means such as public service advertisements and low-carbon promotion, it influences the regulatory efforts of the government, the green demands of consumers, and the investment needs of investors; thus, it subsequently affects enterprises’ GI behaviors (Shahzad et al., 2023). However, few studies have examined the mechanisms linking the LCCPP to enterprises’ GI from the perspective of public environmental concern. This study addresses this gap through the second research question (RQ2): How does China’s LCCPP affect public environmental consciousness?

Previous studies have investigated various internal factors in enterprises that may affect the impact of the LCCPP (Liao et al., 2024; Zheng & Chang, 2023), but few have evaluated the boundary conditions of the relationship between the LCCPP and GI. Therefore, this study introduces enterprises’ internal factors to enrich the research on this relationship. According to the theory of managerial myopia, executives with short decision-making horizons often prioritize short-term projects that yield immediate returns over long-term initiatives that involve higher risks but offer potentially greater rewards (Aghamolla & Hashimoto, 2023). This study addresses this gap through the third research question (RQ3): How does managerial myopia affect the connection between the LCCPP and enterprises’ substantive GI?

The contributions of the study are as follows. First, based on institutional theory, the effect of China’s LCCPP on two distinct types of enterprises’ GI are explored. Unlike prior studies, this study offers more detailed and comprehensive empirical evidence on the GI effects of the LCCPP while providing theoretical support and practical implications for advancing carbon reduction efforts in China. Second, the mediating role of public environmental consciousness between the LCCPP and enterprises’ substantive GI is revealed based on the stakeholder theory. The study enriches the literature on low-carbon pilot initiatives and their impact on enterprises’ GI while providing theoretical references for improving LCCPP implementation. Finally, the moderating impact of managerial myopia on the relationship between the LCCPP and enterprises’ substantive GI is examined. By innovatively identifying the boundary conditions that influence the link between low-carbon city pilots and substantive GI in enterprises, the study offers valuable insights into maximizing the active influence of the LCCPP on enterprises’ GI.

Theoretical analysis and hypothesis developmentLow-carbon city pilot and enterprises’ GIUndertaking substantive GI involves greater challenges, a longer development cycle, and a higher risk of failure compared with low-tech strategic GI (He, 2023; Lian et al., 2022). Consequently, enterprises have relatively weak motivation to pursue substantive GI. Under these circumstances, the LCCPP, as an institutional factor, serves as a key force guiding enterprises in undertaking substantive GI. Institutional theory holds that enterprises, embedded within specific institutional environments, are motivated to fulfill the demands of various stakeholders for gaining legitimacy and acquiring the resources needed for organizational development. Enterprises primarily encounter three types of institutional pressures: coercive, normative, and mimetic (Zhang et al., 2024; Khan & Johl, 2019).

First, coercive pressure primarily originates from the Chinese government, where environmental laws and regulations crucially shape enterprises’ strategic decisions (Krell et al., 2016). Following the implementation of low-carbon policies, the government has enforced mandatory environmental regulations and strengthened administrative oversight to guide enterprises in their green transformation and promote urban low-carbon development (Zhou et al., 2023a). The environmental governance pressure perceived by enterprises has increased significantly. Enterprises undertaking strategic GI face challenges in meeting stringent policy standards due to the low technological sophistication and limited environmental benefits of this type of GI. With the digitalization of environmental governance and the diversification of policy tools, enterprises find it increasingly difficult to gain legitimacy through strategic GI. Thus, the motivation to pursue substantive GI is heightened. Meanwhile, China’s development strategy is shifting from being an innovation-driven nation to becoming an innovation powerhouse, with policy resources increasingly allocated to enterprises that actively engage in substantive innovation. Enterprises often invest time and effort in substantive innovation to secure the resources essential for organizational development. However, enterprises engaging in strategic GI may fail to obtain policy support (Zhou et al., 2023b).

Second, normative pressure mainly stems from the environmental protection practices of competitors (Daddi et al., 2016). Following LCCPP implementation, leading enterprises have proactively engaged in substantive GI to maintain their competitive advantage, thereby attracting resource support from both the government and investors. To enhance their competitiveness, focal enterprises tend to emulate the GI practices of leading enterprises and undertake substantive GI (Zampone et al., 2023). Strategic GI fails to bring significant market advantages to enterprises owing to its low level of innovation and lack of long-term benefits. As a result, enterprises exhibit relatively low motivation to adopt it.

Third, mimetic pressure primarily stems from consumer demand for green consumption, which is regarded as a crucial driving force for enterprises to implement GI. LCCPP implementation increases consumer environmental awareness by promoting eco-friendly behaviors, including energy conservation and low-carbon travel, thereby increasing consumer demand for green consumption. In this case, enterprises’ engagement in substantive GI helps them maintain strong relationships with consumers and sustain long-term business competitiveness (Bataineh et al., 2024). However, strategic GI neither effectively meets the growing consumer demand for green consumption nor strengthens consumer trust and satisfaction. Therefore, LCCPP implementation is more likely to encourage enterprises to pursue substantive GI than to promote strategic innovation activities. Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 LCCPP implementation fosters enterprises’ engagement in substantive GI while leaving strategic GI activities unaffected.

Following LCCPP implementation in China, pilot cities have greatly emphasized low-carbon publicity efforts and actively promoted the concept of a low-carbon economy (Li & Wang, 2023). With rising education levels and the rapid development of social media, low-carbon messaging has become increasingly accepted by the public. Meanwhile, public concern and active participation have gradually increased in response to escalating environmental challenges (Wang et al., 2018). As public environmental awareness continues to grow, active public participation plays an increasingly vital role in efforts related to pollution control, carbon reduction, and sustainable green development.

Public environmental consciousness essentially reflects the public’s exercise of their rights as external monitors, and it also guides and provides feedback to external stakeholders regarding corporate value expectations. Stakeholder theory posits that companies must respond to the interests of multiple groups, including government requirements, consumer demands, and investor expectations related to environmental protection.

At the government level in China, the public expresses environmental demands through the Internet and social media, converting their concerns into pressure signals directed at the government. This situation, in turn, prompts the government to strengthen environmental regulations and administrative supervision. In this process, the government continuously refines environmental protection policies, which impose mandatory constraints on enterprises (Wu et al., 2022). Enterprises are compelled to engage in substantive GI to meet governmental expectations. Simultaneously, heightened public environmental awareness can reduce information asymmetry. This helps prevent potential collusion between enterprises and local governments while reducing instances of greenwashing and low-quality innovation.

At the investor level, as public environmental awareness grows, investors increasingly favor environmentally friendly enterprises, effectively expressing their preferences through financial investment decisions (Wang & Zhao, 2018). To meet the expectations of this key stakeholder group, enterprises must achieve stronger market and capital returns by engaging in high-quality substantive GI activities (He et al., 2022).

At the consumer level, growing public attention to environmental issues has continuously increased consumers’ green demands. Consumers are increasingly prioritizing products that comply with environmental regulations (Mehta & Chahal, 2021) and are even willing to pay a premium for green products (Chaihanchanchai & Anantachart, 2023). To meet the expectations of this key group, companies must adapt their development strategies and prioritize high-quality, substantive GI. This enables them to respond to the growing demand in the green market and enhance brand competitiveness (Tao et al., 2024; Lu et al., 2025). In summary, China’s LCCPP enhances public environmental consciousness. Under pressure from multiple stakeholders, the policy not only encourages the government to strengthen environmental regulations but also stimulates investors and consumers to support GI, thereby promoting substantive GI among enterprises. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 Public environmental consciousness acts as a mediator between the LCCPP and enterprises’ substantive GI.

Managerial myopia refers to the tendency of corporate decision makers to focus excessively on short-term performance and immediate returns while neglecting long-term strategic planning and sustainable investment. Such short-sighted behavior often pushes the management to allocate limited resources to projects that offer quick financial or market gains rather than to those requiring long-term investment and involving higher R&D risks (Smulowitz et al., 2023). Existing studies have found that managerial short-sightedness is a key factor contributing to inadequate investment in R&D and innovation within enterprises (Kraft et al., 2018).

The LCCPP encourages enterprises to undertake substantive GI by offering policy incentives and imposing institutional constraints. This process typically involves extensive efforts in technology R&D, process optimization, and product upgrading, aimed at achieving long-term environmental and economic benefits. However, highly short-sighted managers prioritize short-term returns in their decision-making processes and are more likely to engage in strategic GI. Strategic GI typically entails low technological sophistication and requires minimal investment. It enables enterprises to comply with government environmental regulations quickly but does not lead to substantial technological advancement or profound green transformation (Liu & Zhang, 2023).

In addition, substantive GI typically involves long R&D cycles and high-risk investments while offering limited short-term financial returns. Short-sighted managers who prioritize personal interests or short-term performance may drive enterprises toward superficial, low-impact innovation practices (Wolters, 2023; Lu et al., 2024). Such adoption undermines the long-term effectiveness of policy incentives and innovation outcomes. As a result, the effectiveness of the LCCPP in promoting substantive GI may be considerably reduced, and enterprises may even miss opportunities for technological breakthroughs.

Therefore, managerial short-sightedness not only hinders enterprises’ sustainable development but also weakens the effectiveness of the LCCPP and constrains the fulfillment of enterprises’ ecological and social responsibilities in the green and low-carbon transition (Chintrakarn et al., 2016). Less myopic managers tend to invest significant efforts and resources in high-quality substantive GI. This initiative not only contributes to environmental improvement but also supports enterprises’ sustainable growth under the environmental pressure imposed by the LCCPP. Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 Managerial myopia weakens the promoting influence of the LCCPP on enterprises’ substantive GI.

The theoretical model is shown in Fig. 1.

MethodologyData sourceThis study covers the first batch of pilot cities that implemented the LCCPP in 2010, the second batch in 2012, and the third batch in 2017. The sample consists of listed on China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share markets from 2007 to 2022, with 2007 designated as the base year to avoid the effects of the changes in the 2007 accounting standards on data comparability. The green patent data were sourced from the Chinese Research Data Services, while other data were obtained from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database. The specific processing procedures were as follows: (1) we excluded ST-listed enterprises with abnormal operating conditions; (2) we deleted samples from financial companies; (3) we excluded samples with an asset–liability ratio beyond the range of 0 to 1; (4) we excluded enterprises with substantial missing data in key indicators between 2007 and 2022; and (5) we winsorized continuous variables at the 1 % level in both tails to mitigate the influence of extreme values.

Variable definition and modelingDependent variablesThe number of patent applications better reflects a company’s intention and capability for innovation compared with the number of granted patents. Therefore, following Li and Zheng (2016), this study uses the number of green invention patent applications to measure substantive GI. Moreover, the number of green utility model and design patent applications is utilized as the measurement index of strategic GI. In the estimation process, all patent counts are transformed using the natural logarithm after adding one to address the right-skewed distribution of green patent data.

Independent variableThe Policy manifests whether the city where enterprise i is situated was included in the first, second, or third batch of the low-carbon city pilot in year t. It takes the value of 1 if the enterprise’s city is on the pilot lists in year t and 0 otherwise.

Control variablesThe board size (Board) is determined by the logarithm of the director count. The proportion of independent directors (Indr) is calculated by dividing the number of external board members by the total number of directors, indicating the level of independence of the board. Enterprise ownership (SOE) is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the enterprise is state-owned and 0 otherwise. The asset–liability ratio (LEV) is defined as total liabilities divided by total assets. The management expense ratio (Mfee) is calculated as management expenses divided by operating revenue; a higher value indicates more severe agency problems, which may hinder enterprises’ GI. Enterprise growth (Grow) is determined by the change in main business income from the previous period to the current period i, relative to the previous period’s income. Rapidly growing enterprises are generally better equipped to engage in GI. Enterprise size (Size) is measured as the logarithm of the number of employees. Enterprise age (Age) is indicated by the logarithm of the number of years since the enterprise went public. According to the lifecycle theory, an enterprise’s innovation capability varies across different stages. Tobin’s Q (Q) is computed as the market value divided by total assets. Return on assets (ROA) is calculated as net profit divided by total assets, which indicates the efficiency of asset utilization. The shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder (Top1) refers to the percentage of shares held by the largest shareholder. Executive incentives (Incen) are measured as the logarithm of the total compensation of the top three executives. Finally, ownership concentration (Eqco) is measured as the ratio of the shares held by the top 10 shareholders to the total number of shares outstanding.

ModelingThe difference-in-differences (DID) method is an econometric approach widely used in policy evaluation. It estimates the causal effect of a policy by comparing changes in the treatment and control groups before and after policy implementation. To test the influence of the LCCPP on enterprises’ substantive and strategic GI, this study designates the provinces and cities that implemented the policy as the treatment group; the remaining cities serve as the control group. The DID model is constructed as follows:

where SubGIit is the number of green invention patent applications filed by enterprise i in year t, StrGIit is the number of green utility model and design patent applications filed by enterprise i in year t, and Policyit is the core explanatory variable that signifies whether the enterprise is subject to a policy shock in year t. If the city where the enterprise is located is included in the first, second, or third batch of pilot cities in year t, Policyit takes a value of 1; otherwise, it is 0. The core coefficients α1 and ϕ1 capture the effects of the LCCPP on substantive and strategic GI, which are the primary focus of this study. If α1 is statistically significantly positive, it suggests that the LCCPP promotes substantive GI. If ϕ1 is not statistically significant, it indicates that the LCCPP has no effect on strategic GI. Additionally, Controls denotes the set of the control variables, γt represents time fixed effects, μi represents province fixed effects, and εit is the random error term.Result analysisDescriptive statisticsTable 1 shows the results of the descriptive statistical analysis for each research variable. According to the table, for enterprises’ substantive GI, the mean of the natural logarithm of green invention patent applications is 0.24, while the median is 0. This indicates that the level of substantive GI among the sample enterprises is generally low, with most falling below the average level. Similarly, the mean value of strategic GI is 0.20 and the standard deviation is 0.527. These values indicate that the level of strategic GI is generally low among enterprises, with considerable variation across the sample. All other variables fall within the acceptable ranges.

Descriptive statistics.

This study employs the DID method for regression analysis, and the corresponding results are shown in Table 2. The estimated coefficient of the core explanatory variable on substantive GI is 0.0322 according to column (1). This positive coefficient is statistically significant at the 5 % level, suggesting that the LCCPP promotes enterprises’ substantive GI. This finding aligns with the purposes of the LCCPP. The conclusion is also broadly consistent with the findings of Xu and Cui (2020), who showed that the LCCPP significantly increases the total number of green patent applications as well as the number of green invention patent applications filed by enterprises. However, the regression results in column (2) show that the estimated coefficient for the core variable on strategic GI is 0.0139. Although this coefficient is positive, it is not statistically significant, indicating that the policy’s implementation did not enhance enterprises’ level of strategic GI. This finding contrasts with some results obtained by Xu and Cui (2020), who concluded that the LCCPP also promotes the number of utility model patent applications filed by enterprises. This is attributed to the fact that strategic GI products are less technologically advanced, which may hamper enterprises’ ability to maintain long-term competitiveness. By contrast, substantive GI ensure favorable environmental performance and offers competitive advantage; thus, it is considered a solid foundation for companies’ development (Granados et al., 2024). The LCCPP imposes coercive and normative institutional pressure on enterprises, compelling them to improve public disclosure and environmental compliance standards. To secure policy support and maintain legitimacy and reputation, enterprises are more inclined to invest in substantive GI that yields tangible emission reduction benefits, which coincide with the LCCPP’s objectives (Li et al., 2023).

Benchmark regression results.

Note: In parentheses are standard errors, ***, **, and * represent the significance at the 1 %, 5 %, and 10 %, respectively.

For the DID estimation to be valid, the parallel trends assumption should hold between the control and treatment groups. In other words, the number of green patent applications in both groups should exhibit similar time trends prior to LCCPP implementation. This similarity ensures that any observed differences after the policy can be attributed to the policy itself. This analysis follows the approach of Koltai et al. (2022), involving the construction and visualization of time-specific dummy variables to estimate regression coefficients. As shown in Fig. 2, the coefficients of the dummy variables for both dependent variables are not significantly different from zero in the three pre-policy periods, indicating that the parallel trends assumption holds. However, the number of enterprises’ green patent applications significantly increases after the policy is implemented. Therefore, the parallel trend assumption is validated.

Placebo testFollowing the approach of Song et al. (2019), a placebo test was conducted to account for potential unobservable factors. The procedure involved using a computer to randomly generate a pseudo-core explanatory variable, Policy, for regression analysis. The estimated coefficients from 1000 random samples were then plotted using a kernel density distribution, as shown in Fig. 3. The figure displays the distribution of estimated coefficients for both substantive GI and strategic GI. The estimated coefficients of the core explanatory variable mostly cluster around zero, and the p-values from the random simulations are mostly greater than 0.1. This finding indicates significant differences between the coefficients estimated from random simulations and the true coefficients. Therefore, the validity of the placebo test was confirmed.

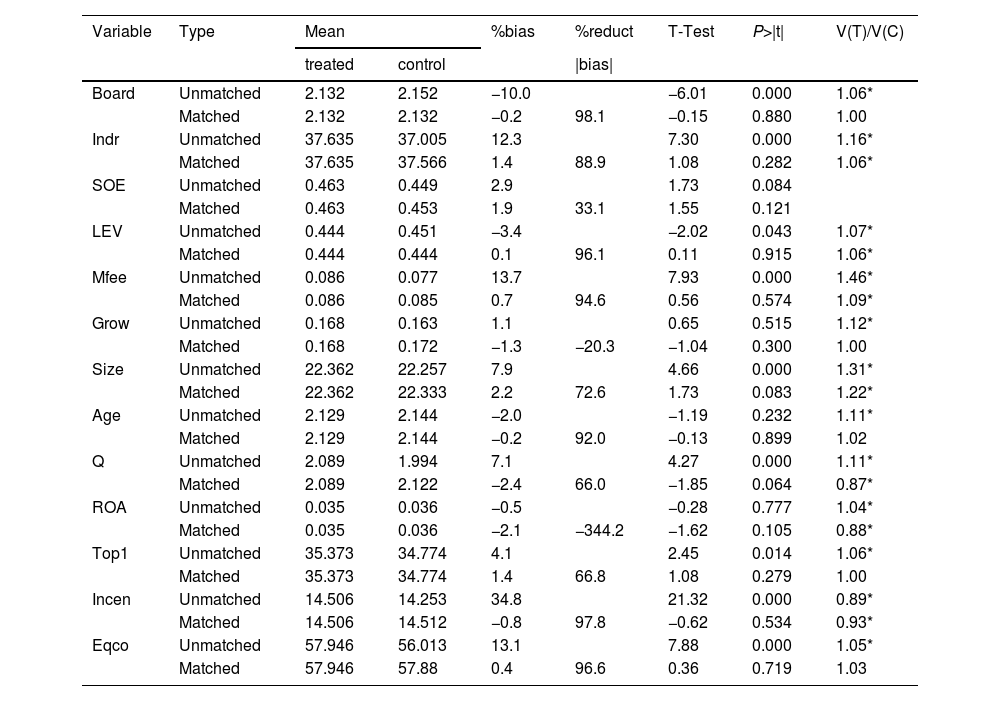

Propensity score matchingAlthough the DID method can identify the net effects of the LCCPP on enterprises’ substantive innovation, sample selection bias may arise from differences between pilot and non-pilot cities that extend beyond the policy itself. To address this issue, this study adopts the approach of Dusengemungu et al. (2023) and conducts a PSM–DID test. In this procedure, a Logit model is used, incorporating variables such as board size (Board), proportion of independent directors (Indr), enterprise ownership (SOE), asset–liability ratio (LEV), and management expense ratio (Mfee) as covariates. The treatment group is matched to the control group using a 1:5 nearest-neighbor matching method. Table 3 reports the balance test results before and after matching. According to Rosenbaum and Rubin (1985)), a standardized difference of <20 % after matching indicates effective balance. As shown in Table 3, the post-matching standardized differences are all below 5 %, indicating a high level of balance between the groups. The common support assumption is verified after sample matching. Fig. 4 shows that most samples fall within the common support range after matching, suggesting that the common support condition is satisfied. On this basis, the DID estimation is conducted. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 4 show that the study’s conclusions remain robust after propensity score matching. Specifically, the LCCPP has significantly promoted substantive GI in the pilot regions, whereas its effect on strategic GI is not statistically significant.

The balance test of propensity score matching.

Note: ***, **, and * represent the significance at the 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % levels, respectively. The values in parentheses are standard errors statistics value.

Results of other robustness tests.

Note: In parentheses are standard errors, ***, **, and * represent the significance at the 1 %, 5 %, and 10 %, respectively.

The new Environmental Protection Law, officially implemented in 2015, explicitly defines the responsibilities of enterprises in environmental governance. This development may influence enterprises’ substantive GI. This study introduced a policy dummy variable to control for the impact of the new Environmental Protection Law for mitigating potential interference. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 4 report the regression results, which reveal that the conclusion remains robust.

Managing industry trendsIndustry factors may induce variations in enterprises’ GI levels. Although some studies have attempted to control for these effects by incorporating industry-level variables, this approach may not fully capture all influencing factors. Therefore, to better account for industry-level factors, this study introduces interaction terms between industry and time trends. The results are shown in columns (5) and (6) of Table 4. As observed, the results remain consistent with the benchmark regression findings even after controlling for industry time trends.

Mechanism analysisMediation effect analysisThe preceding research findings indicate that the LCCPP promotes enterprises’ substantive GI; however, its impact on strategic GI is not statistically significant. Therefore, the mechanism through which the LCCPP influences enterprises’ substantive GI warrants further investigation. Based on the theoretical framework discussed in the preceding sections, this study analyzes the influence of the LCCPP on substantive innovation from the perspective of public environmental consciousness, which is introduced as a mediating variable. Following the model proposed by Wen and Ye (2014) and employing the Sobel test to verify the mediation effect, we construct the following mediation model:

In these equations, Controls, γt, μi, and εi are consistent with those in Model (1). This study follows the methodology of Wang and Zhao (2018), who used “pollution” as a keyword on Baidu to extract the annual average index across regions from the Baidu Search Index. This index is employed as a metric for public environmental consciousness. Owing to substantial missing data prior to 2010, this study restricts its analysis to data from 2010 onward.

The results of the mediation analysis, which examined the role of public environmental consciousness in the relationship between the LCCPP and enterprises’ substantive GI, are presented in columns (1)–(3) of Table 5. The regression coefficient of the Policy variable is 0.000. Although the coefficient is smaller than 0.043, it is not statistically significant, which demonstrates that public environmental consciousness plays a fully mediating role between the LCCPP and enterprises’ substantive GI. The Sobel Z statistic is 6.88, which is significant at the 1 % level, confirming the robustness of the mediation effect.

Results of the mechanism analysis.

Note: In parentheses are standard errors, ***, **, and * represent the significance at the 1 %, 5 %, and 10 %, respectively.

The pilot initiative, which is implemented through means such as public service announcements and low-carbon promotion, cultivates residents’ low-carbon literacy, enhances environmental awareness, and subsequently increases public environmental consciousness. The rise in public environmental concern encourages enterprises to engage in substantive GI. Heightened public environmental concern effectively prompts local governments to attend to and supervise enterprises’ low-carbon development, while strategic innovation often falls short of satisfying legitimacy requirements (Bakaki et al., 2020). Additionally, increasing public environmental awareness compels enterprises to produce high-quality green products and offer superior green services in order to maintain a competitive advantage. Consequently, enterprises are motivated to pursue substantive GI to meet the public demand for green products. Moreover, investor preferences in the capital market encourage enterprises to implement substantive GI to meet market demands (El Ouadghiri et al., 2021). These outcomes are consistent with the intended objectives of the LCCPP, which aims to promote genuine emission-reducing innovation through broad-based environmental engagement.

Moderation effect analysisThe main analysis revealed that some managers adopt a short-term decision-making perspective. Owing to the high costs and uncertain risks associated with substantive GI, managers tend to favor strategic GI, which offers immediate short-term benefits. Such a short-term orientation, especially under external pressures, weakens the promotional influence of the LCCPP on enterprises’ substantive GI. This study introduces managerial myopia as a moderating variable and examines its impact on the relationship between the LCCPP and enterprises’ substantive GI. The model is constructed as follows:

In this equation, the variables Controls, γt, μi, and εi are consistent with those in Model (1). Following Hu et al. (2021), the data are obtained from the WinGo Textual Analytics Database. As shown in column (4) of Table 5, at the 1 % level, the interaction term between managerial myopia and the explanatory variable is significantly negative at the 1 % level, indicating that managerial myopia weakens the stimulative influence of the LCCPP on substantive GI. In other words, when managers demonstrate higher levels of myopia, enterprises are more likely to engage in strategic GI to comply with the LCCPP. Such enterprises prioritize short-term gains over long-term sustainability, which undermines the policy’s intention to encourage meaningful and lasting carbon reductions through high-quality innovation. This finding underscores the importance of managerial foresight and long-term orientation in aligning corporate behavior with the core objectives of the LCCPP.

Heterogeneity analysisHeterogeneity in technological attributes across industriesThe impact of the LCCPP on GI may vary across industries with different technological attributes. Following prior studies, enterprises in industry codes C27, C34–C41, C43, G53–G56, and G58–G60 are defined as technology-intensive, while the others are considered labor-intensive. As shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 6, the coefficient of the core variable for technology-intensive enterprises is significantly positive at the 1 % level. In contrast, the coefficient for labor-intensive enterprises is not statistically significant. Moreover, a Fisher’s permutation test is performed using the bdiff command to assess the statistical significance of the differences between groups. The empirical p-values for the Policy coefficient for the technology-intensive enterprises are significant at the 1 % level, indicating that the LCCPP exerts a more significant positive effect on substantive GI in such enterprises. This finding may be attributable to the fact that the policy support and technical resources provided by the LCCPP are better aligned with the needs of technology-intensive enterprises, which typically have a strong technical foundation and robust R&D capabilities that facilitate GI.

Results of heterogeneity test.

Note: In parentheses are standard errors, ***, **, and * represent the significance at the 1 %, 5 %, and 10 %, respectively.

Enterprises of different types under the same LCCPP may adopt distinct GI strategies. As shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 6, the LCCPP significantly promotes enterprises’ substantive GI with a high fixed asset ratio. In contrast, its effect on those with a low fixed asset ratio is not statistically significant. This result may be attributable to the fact that enterprises with a high fixed asset ratio often rely on highly specialized production equipment with long operational cycles. Under the constraints of the LCCPP, these enterprises have difficulty achieving compliance by phasing out equipment, which compels them to improve the efficiency of their existing assets through GI.

DiscussionFirst, this study investigates whether LCCPP implementation in China can stimulate enterprises to engage in substantive or strategic GI. The findings indicate that the LCCPP encourages enterprises to engage in substantive GI, but it does not significantly foster strategic GI. The conclusion is consistent with Liu et al.’s (2025) study, which showed that the LCCPP significantly promoted substantive GI in cities but had no significant impact on strategic GI. Unlike existing studies that primarily focus on city-level data, the present study examines the micro-enterprise level. It empirically analyzes corporate green patent data to reveal the impact of the LCCPP on two types of GI: strategic and substantive.

According to the institutional theory, enterprises become more concerned with managing their reputation among stakeholders due to external pressure, which reduces motivation for strategic GI (Testa et al., 2018). Enterprises are more likely to pursue substantive GI to demonstrate their commitment to environmental responsibilities and earn stakeholder approval. As a result, they engage in substantive GI to secure market share and maintain a green competitive advantage. By contrast, the output and impact of strategic GI are relatively limited and do not substantially contribute to business advancement. Therefore, LCCPP implementation promotes substantive GI but does not significantly foster strategic GI.

Additionally, the LCCPP operates under a governance model in which the central government sets the policy direction, while local governments are responsible for implementation and funding. Being selected as a pilot city represents both an honor and a responsibility (Xu & Cui, 2020). Particularly under conditions of political competition, local government officials in pilot areas show heightened enthusiasm for governance, which may in turn suppress enterprises’ motivation for strategic GI. Consequently, LCCPP implementation drives enterprises to engage in substantive GI but does not significantly encourage strategic GI, which is consistent with the policy’s carbon reduction objectives.

Second, this study identifies the key mediating mechanism through which China’s LCCPP influences substantive GI. The results, shown in Table 5, indicate that LCCPP implementation enhances substantive GI by increasing public attention to environmental issues. Hypothesis 2 is therefore supported. These findings are consistent with those of Li and Wang (2023), whose study suggests that various pilot regions adopted measures such as public service announcements and low-carbon advocacy after LCCPP implementation to improve public low-carbon literacy, enhance environmental awareness, and encourage low-carbon consumption preferences. Similarly, Liu and Xu (2022) found that the LCCPP promotes a shift in residents’ behavior toward a green lifestyle by increasing environmental awareness and promoting green consumption habits, thereby helping break the carbon lock-in effect in daily life.

This study not only reveals the positive impact of the policy on residents’ environmental awareness but also investigates how this heightened awareness motivates enterprises to actively engage in high-quality GI in response to external low-carbon policy pressures. By raising public environmental awareness, the LCCPP also motivates stakeholders such as the government, consumers, and investors to hold enterprises to higher environmental standards, indirectly encouraging them to pursue substantive GI. This mechanism of influence is fully consistent with the intended objectives of the LCCPP, which seeks to foster a low-carbon culture and promote authentic emission-reducing innovation through broad societal engagement.

Third, this study examines the impact of managerial myopia on the substantive GI undertaken by enterprises in response to low-carbon policy pressures. Managerial myopia refers to managers having a shorter decision-making horizon, favoring minor innovations that offer short-term benefits over substantive GI, which yields long-term benefits for the organization (Schuster et al., 2020). Managerial myopia weakens the enabling effect of the LCCPP on the development of enterprises’ substantive GI. The results in Table 5 confirm the validity of Hypothesis 3. This finding is consistent with prior research: Sharma et al. (2018) suggested that short-sighted managers tend to favor short-term investments to avoid the risks linked to long-term R&D projects. These managers tend to choose investment projects with short durations, quick cash returns, and easily recoverable profits. The characteristics of financialized assets closely align with the investment preferences of short-sighted managers, prompting them to pursue more financialized investments (Yu, 2022).

Previous research has focused on the adverse effects of managerial myopia on overall R&D investment and enterprise performance. Within the specific context of low-carbon policies, this study further examines how this effect manifests in corporate GI behavior. It not only confirms the adverse moderating effect of managerial myopia on GI but also offers valuable theoretical insights and practical guidance for advancing enterprises’ long-term green transformation within the framework of low-carbon city pilot policies. These findings underscore the fundamental aim of the LCCPP to stimulate high‑quality, emission‑reducing innovations over the long term. By demonstrating that managerial myopia hinders this objective, the study underscores the importance of cultivating strategic, long-term vision among managers and enhancing corporate environmental accountability to ensure that low-carbon policies achieve their intended outcomes.

Conclusions and implicationsConclusionsThe following conclusions can be drawn.

- (1)

China’s LCCPP promotes GI within enterprises, significantly enhancing substantive GI while having little to no effect on strategic GI in the context of carbon neutrality. This impact is consistent with the objectives of the LCCPP. Results remain robust after multiple tests, including parallel trends analysis, placebo tests, and PSM–DID estimation.

- (2)

The primary mechanism through which China’s LCCPP promotes the enterprise’s substantive GI is by increasing public environmental awareness. Low-carbon outreach and education campaigns in pilot cities have increased public concern for environmental protection. As a result, enterprises face growing environmental and social pressures and actively pursue high-quality GI to gain legitimacy and fulfill stakeholder expectations.

- (3)

Managerial myopia weakens the positive effect of the LCCPP on substantive GI. Highly myopic managers, who prioritize short-term economic gains without regard for long-term organizational benefits, impede the development of substantive GI. In contrast, less myopic managers place greater emphasis on sustained enterprise growth and are more willing to allocate resources and effort toward developing high-quality, substantive GI.

- (4)

The impact of the LCCPP on enterprises’ substantive GI varies by industry, technological attributes, and fixed asset ratios. The policy’s innovation incentive effect is stronger in technology-intensive enterprises than in labor-intensive ones. Moreover, it positively affects substantive GI only in enterprises with a high fixed asset ratio while having no significant impact on those with a low fixed asset ratio.

First, this study enriches the theoretical framework in the field of LCCPP and enterprises’ GI. Existing studies mainly focus on the overall impact of the LCCPP on GI or urban-level GI, rarely investigating how different motivational factors lead to heterogeneous GI behaviors among enterprises. This study categorizes enterprises’ GI into substantive and strategic types and examines how the LCCPP differentially impacts the two forms, drawing on the institutional theory. In this way, the study supplements and extends the existing theoretical framework, providing a sound basis for the scientific formulation and effective implementation of the LCCPP.

Second, this study deepens the understanding of the mediating mechanism through which the LCCPP influences enterprises’ GI. Existing research has assessed this mechanism predominantly from the perspectives of cost input, resource allocation, and strategic decision making. However, few studies have adopted the perspective of public environmental awareness. This study addresses this gap by examining the mediating role of public environmental awareness in the relationship between the LCCPP and enterprises’ GI based on the stakeholder theory. Thus, this study not only enriches the theoretical explanation of the policy’s influence mechanism but also provides new insights and practical guidance for governments and enterprises in formulating and implementing low-carbon policies. In this way, public opinion and oversight can be harnessed to drive enterprises’ green transformation.

Finally, this study expands the research scope on the relationship between managerial myopia and the effectiveness of the LCCPP. Although previous studies have examined the impact of such policies on enterprises’ GI from the perspectives of property rights and enterprise size, few have investigated the potential influence of managerial myopia. By incorporating this variable, this study finds that managerial myopia significantly reduces the effectiveness of the LCCPP in promoting enterprises’ GI, highlighting the critical role of internal managerial decision-making characteristics in policy transmission. This understanding offers robust theoretical support for the effective implementation of such policies and provides valuable insights for policymakers.

Managerial implications- (1)

The scope of the pilot program should be further expanded, and the policy incentives and supervision mechanisms should be more clearly defined. Given the positive impact of the LCCPP on enterprises’ GI, the government should consider the following measures. First, the government should summarize the successful experiences of existing low-carbon pilot cities; develop a set of operational, replicable, and scalable models; and encourage more cities to participate actively in low-carbon pilot projects. Second, the policy supervision mechanism should be strengthened to prevent enterprises’ opportunistic behavior. Higher-level governments should establish a regular progress-tracking system and invite expert teams to provide targeted guidance to pilot areas, thereby ensuring the effective implementation of various policy measures. Finally, policymakers should adjust the evaluation criteria for enterprises’ GI achievements, enhance market-based identification mechanisms, and prioritize support for enterprises that demonstrate high-quality performance in green patents and technology R&D. This approach would help prevent enterprises from relying solely on short-term and low-level strategic innovations to obtain policy subsidies.

- (2)

Publicity and education efforts should be strengthened, and a robust mechanism for public participation and supervision should be established. Given that public environmental consciousness plays a key role in fostering enterprises’ GI during LCCPP implementation, the government should adopt the following measures. First, the government should clearly stipulate that each pilot area organizes regular environmental protection campaigns; widely disseminate low-carbon and environmental protection concepts through channels such as television, the Internet, and social media; and further enhance public environmental awareness and participation. Second, a standardized online complaint and reporting platform should be established to enable the public to conveniently report enterprises’ environmental violations or greenwashing practices. In addition, the responsibilities of each department within the supervision mechanism should be clearly defined, and the results of supervision should be disclosed regularly to enhance the transparency and credibility of policy implementation.

- (3)

Executive training and incentive mechanisms should be enhanced, and a comprehensive system for long-term strategic decision making and performance evaluation should be established. First, each pilot area should regularly organize seminars focused on green transformation and long-term innovation for senior executives. These seminars should incorporate expert presentations, case studies, site visits, and other approaches to enhance managers’ strategic understanding of GI and sustainable development, cultivate a long-term development mindset, and reduce reliance on short-term, profit-driven behavior. Second, the government should improve both incentive and regulatory mechanisms by incorporating GI outcomes into the performance evaluation systems of senior corporate executives. Relevant policy documents should be issued to clearly outline additional financial subsidies, tax incentives, and preferential loans designed to support substantive GI projects. Furthermore, a regular evaluation and information disclosure mechanism should be established to ensure that enterprises report their investments and achievements in GI activities.

- (4)

Enterprises’ specific circumstances should be considered, and customized financial support policies for low-carbon transition should be implemented. In promoting low-carbon city pilot projects, a one-size-fits-all approach is unsuitable. Because GI involves high investment costs, long lead times, and substantial risks, many enterprises, particularly those with a high fixed asset ratio, tend to adopt a strategic response mindset. Therefore, these enterprises deserve greater attention and targeted financial support. Meanwhile, training and educational programs related to GI should be organized to enhance enterprises’ awareness and capacity for sustainable development. Differentiated support measures should also be provided for enterprises with varying technological attributes across different industries. By optimizing financial services and promoting diversified financing channels, the financing environment can be improved to fully mobilize enterprises’ enthusiasm for substantive GI.

This study examines the impact of the LCCPP on substantive GI, taking into account the role of public environmental awareness, and further explores how managerial myopia moderates this relationship within the context of carbon neutrality. Several limitations of this study should be addressed in future research. First, this study primarily investigates the impact of managerial myopia, which is an internal organizational factor, on enterprises’ GI level. However, it fails to account for external regulatory mechanisms, such as media influence and industry competition. Future research should adopt a more integrated perspective by considering both internal and external influencing factors. This approach helps clarify how the interaction between internal and external factors influences the relationship between the LCCPP and enterprises’ substantive GI. Second, this study focuses exclusively on the effect of the LCCPP on enterprises’ GI. Future research could explore other innovation incentive policies tailored to the unique characteristics of individual enterprises to better assess the effectiveness of diverse environmental regulatory tools across different types of enterprises.

FundingThis study was supported by Major Project of the National Social Science Fund of China (NO.24&ZD114).

CRediT authorship contribution statementJintao Lu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Zhencui Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Xue-Li Chen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis. Xue Yu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Formal analysis. Malin Song: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Formal analysis.

Variables and abbreviations.