Green skills and capabilities in organisations are important enablers of net-zero transition as they determine firms’ ability to adopt sustainability as a core business strategy. This study conducts a systematic literature review of 84 scholarly articles and 7 industry publications to examine the conceptualisation of green skills and green capabilities in firms, their influence on firms’ financial performance, and the factors shaping these complex relationships. Findings reveal that the green skills and green capabilities concepts are broad and ambiguously defined, necessitating greater conceptual clarity, especially with respect to how the green skills and capabilities relate to each other. Accordingly, the study develops a framework outlining different green skill and capability typologies and their interconnections. Additionally, six key performance categories—(1) costs, (2) profitability, (3) efficiency and productivity, (4) firm growth, (5) liquidity, and (6) market performance— are identified inductively, with evidence from the literature indicating that both green skills and green capabilities positively impact each of these areas. Results suggest that while the overall effect of green skills and capabilities on financial performance is positive, several contextual factors, such as firm size, sector, and region, influence this relationship. The study highlights the most significant caveats and their implications, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the knowledge–performance link for the net-zero transition.

The Paris Agreement set a global warming target of no more than 2.0°C above pre-industrial levels, triggering interest on the part of both general public and governments in better regulating emissions from industrial production (UNFCCC, 2015). Consequently, firms are under growing stakeholder pressure to make pro-environmental changes to their business strategies (He et al., 2024; Li, 2022; Singh et al., 2022). “Business as usual” is no longer a feasible option for meeting economic, environmental, and social needs; thus, the active integration of sustainability has become central to business strategy, reflected in a fast-growing body of corporate sustainability literature across the fields of business, management, and economics (Ferreira Gregorio et al., 2018). This paper presents a systematic review of the literature that examines how firms’ unique green skills1 (GS) and green capabilities2 (GC) affect their financial performance.

The literature on business sustainability builds on the foundations of the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm (Barney, 1991; Wang et al., 2024). RBV argues that a firm’s resources and capabilities are sources for improved organisational performance, but are not evenly distributed across firms, which leads to persistent performance differentials (Carton & Parigot, 2021). As sustainability literature grew over the years, the RBV was criticised for overlooking the role of natural resources and their finite supply (Bastian et al., 2018). In response, the natural-resource-based view theory (NRBV) emerged to address these shortcomings (Hart, 1995). NRBV sheds light on the importance of GS and GC for pollution prevention, product stewardship for eco-products, and introducing or implementing clean technologies (Hart, 1995; Prahalad & Hart, 2002). Strategic management research has since embraced NRBV to explore the role of employees’ GS and firms’ GC as a potential driver of firms’ financial performance (Martínez‐del‐Río et al., 2012; Trentin et al., 2015; Wong et al., 2012).

This study aims to shed light on the literature that presents gaps in our understanding of the relationships between GS, GC, and firm performance. Firstly, the literature that looks at GS and GC reflects a lack of consensus on what constitutes GS and GC, and how these important concepts relate to each other within an organisation and, more broadly, at industry or economy level. The literature often uses the definition of GS as the “technical skills, knowledge, values and attitudes needed in the workforce to develop and support sustainable social, economic and environmental outcomes in business, industry and the community” (OECD, 2014, p. 164), while another definition describes GS as “the knowledge, abilities, values, and attitudes needed to live in, develop and support a society which reduces the impact of human activity on the environment” (CEDEFOP, 2012, p. 20). Although there are many definitions of GS, only a handful of articles and pieces of grey literature identify specific GS in practice. Similarly, the literature on GC has complexities around conceptualisation. While various definitions of GC exist, countless adaptations and nuances obscure their conceptual clarity. For example, Khan et al. (2023b, p. 2024) define GC broadly as the “organisational capacity that leverages current resources and expertise to grow its skill to adapt to dynamic market challenges”. Similarly, Xing et al. (2020, p. 4) refer to GC as the ability “of firms to develop their green organisational capability to respond to market changes by using existing resources and a range of knowledge renewal activities”. Such definitions are in line with the assertion that GC align closely with broader organisational knowledge and capabilities to support firm strategy (Shaharudin et al., 2023). On the other hand, narrower and more specific terms are also widely employed to refer to GC, such as “green innovation capabilities” (Nguyen et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023a; Zhu et al., 2023) and “green political capability” (Yi & Demirel, 2023), emphasising the uniqueness of GC and how they differ from broader organisational capabilities. Furthermore, the literature rarely considers GS and GC jointly or as interconnected elements in an organisation, leaving gaps in our knowledge of where and how GS and GC are situated within the organisational knowledge structures. Secondly, this semantic and relational ambiguity around GS and GC is compounded by the wide range of firm performance indicators (e.g. return on assets, earnings per share, working capital, market share growth, and inventory holding costs, to name but a few) used in empirical studies that explore the impact of GS and GC on firm performance (Lee et al., 2012; Ramanathan et al., 2016). It is thus hard to see general trends and differences in how GS and GC affect different measures of firm performance.

Targeting the abovementioned issues, this systematic literature review aims to (1) map and clarify definitions of GS and GC, (2) explore their relationship, (3) analyse their effects on six dimensions of financial performance (profitability, cost efficiency, productivity, growth, liquidity, and market performance), and (4) identify contextual factors (e.g., firm size, sectoral regulations) that shape these relationships. It is worth noting that a number of previous systematic reviews in this area have attempted to investigate GS, GC, and their organisational implications. For example, Dzhengiz and Niesten (2020) examined environmental competencies as individual skills, but did not explore how these environmental competencies affected financial outcomes or interacted with the broader range of capabilities. Similarly, Cabral and Dhar (2021) analysed the role of green competencies in firms’ sustainability performance, but not in their financial performance. Our study builds on these prior systematic reviews and advances current literature in two main ways. Firstly, it considers and classifies a broad set of GS and GC and explores them as interdependent constructs. In doing so, it proposes a framework that connects micro (GS) and macro (GC) perspectives. Secondly, by systematically mapping the GS and GC effects across six financial performance indicators, this review clarifies the findings of the empirical literature, revealing the common effects of GS and GC on firm performance and the contextual patterns (e.g., sectoral contexts) that shape these effects. Through these contributions, the paper offers insights for future research on GS and GC, as well as practical recommendations for decision-makers in firms on how best to align human capital (GS) and organisational routine (GC) to adapt better to the net-zero transition.

MethodologySystematic literature reviewThis section describes the research protocol adopted in our systematic literature review (SLR) study. SLR was chosen for the structural identification of gaps in the literature related to GS and GC as it is a type of methodology commonly employed in business and management research. (For similar studies, see Amui et al., 2017; Dzhengiz & Niesten, 2020; Hansen & Schaltegger, 2016; Parris & Peachey, 2013; Watson et al., 2018.) SLR helps provide both theoretical and methodological understanding of the research area and lends insight into future developments (Boland et al., 2023). An additional benefit of conducting an SLR is its utility in interpreting qualitative and quantitative findings and highlighting gaps raised by earlier literature (Centobelli et al., 2020).

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure that this SLR complied with an established standard methodology. The guidelines allow for further improved quality assurance of the revision process, replicability, and scientific adequacy by utilising the provided guideline checklist (Page et al., 2021). The next section describes the research protocol, including the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the papers considered, data extraction, and analysis.

Search strategy and data sourcesThree electronic databases or platforms—Web of Science, EBSCOHost Business Source Ultimate, and Scopus—were systematically searched using the keywords reported below. The search focused on peer-reviewed papers written in English between 1995 and 2023 and relevant grey literature identified via citation tracking. All references were gathered in an EndNote database. The search terms initially proposed, which arose from the most pertinent preliminary literature, were gradually updated by snowballing additional phrases based on further understanding of the literature and the recommendations of field experts, generating a final set of keywords. During this iterative process, the authors met regularly to discuss the most relevant search strings to include as constituents of the final set of keywords and phrases that best represented the primary focus of this paper (Tranfield et al., 2003). The final set of keywords and Boolean operators is presented in Table 1.

Search strategy with keywords and boolean operators.

The first set of keywords reported in Table 1 includes various terms describing green skills and capabilities, while the keywords in the second set capture a firm’s economic performance, employing a combination of objective and subjective terms to describe economic performance outcomes. “Objective terms” refers to economic performance outcomes strictly relating to a firm’s financial performance, including profit, growth, and market value (Andrews et al., 2006). “Subjective terms” typically refers to firm performance outcome measures pointing to non-financial performance (Joshi et al., 2011), such as a firm’s reputation, stakeholder satisfaction (Freeman, 1984), or competitiveness (Porter, 1985). The rationale behind combining objective and subjective performance measure outcomes is that doing so compensates for the “deficiencies of using either in isolation”3 (Andrews et al., 2006, p. 18).

In the first screening phase, in order to ensure a foundation of empirical data by prioritising studies with objective measures, we excluded papers that focused solely on subjective performance outcomes. This approach streamlined the review process, allowing us to focus on comprehensive analyses integrating objective and subjective measures in the full-text review phase that followed.

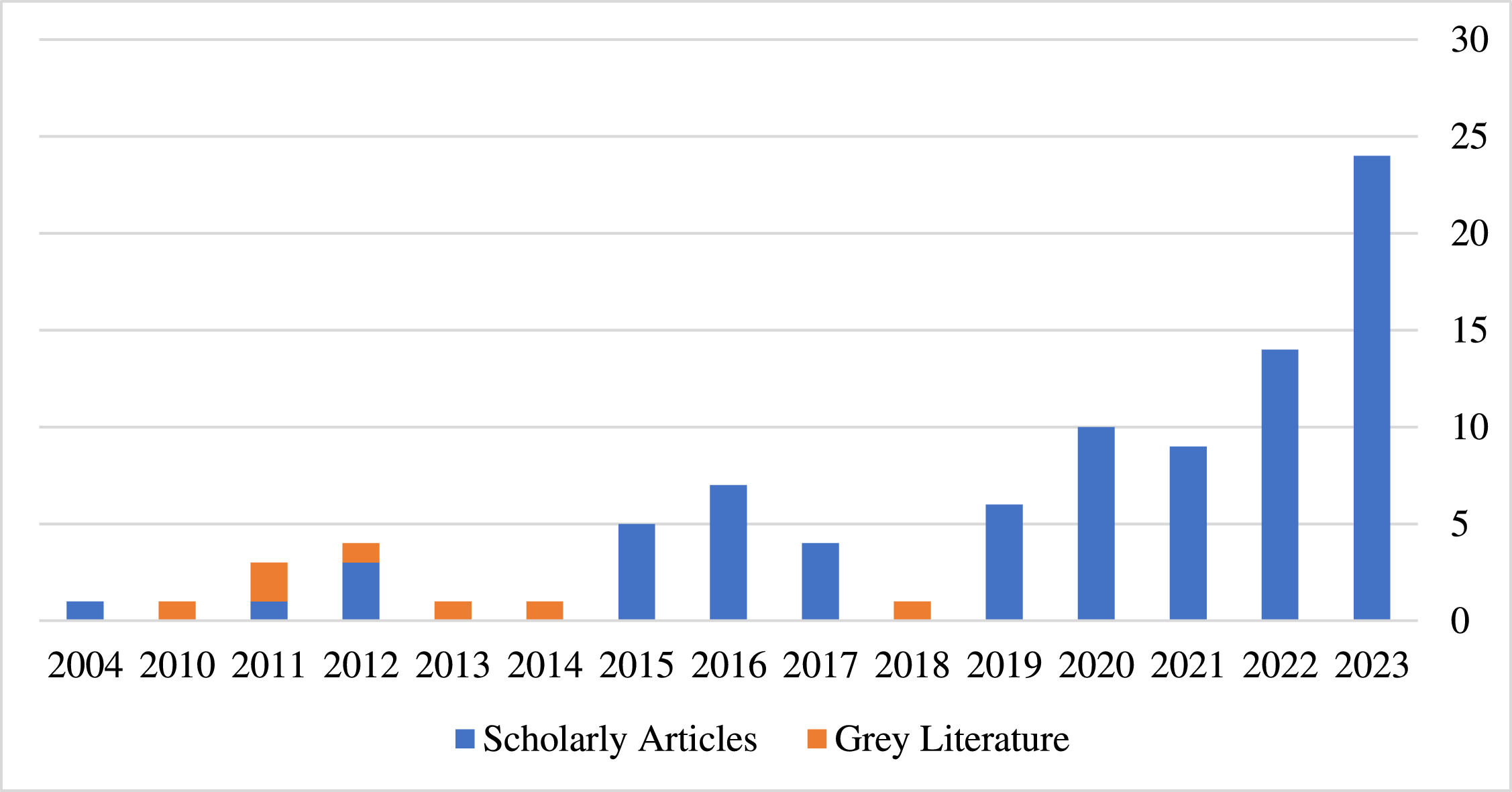

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe SLR selection criteria were established with a clear focus on the initial research question, to ensure that the reviewed articles were directly relevant to the topic (Tranfield et al., 2003). The first phase of article screening reviewed all titles, keywords, and abstracts. The inclusion criteria consisted of (a) papers that included the selected search terms in the abstract and keywords (where identified), (b) papers written in the English language, and (c) papers published between 1995 and 2023.4 The starting point for the review was chosen to correspond with the theoretical foundation of the relevant literature, being the NRBV of the firm, starting with the seminal publication by Stuart Hart in 1995 (Hart, 1995). See Fig. 1 for the number of articles and items of grey literature published between 1995 and 2023.

Articles were excluded when (a) they were not written in the English language, (b) there was no full text available, (c) they were non-peer-reviewed papers, including retracted publications, conference papers, and proceedings papers, (d) they had been published outside the set time frame, and (e) they focused on organisational entities other than firms. All duplicate papers were removed.

In the second phase of screening, the full texts of all remaining articles were analysed, assessed and reviewed in detail to identify all studies that were relevant for final inclusion. All the quality assessments and data extractions were executed on an evidence-based table, where data was gathered and organised for analysis. The criteria for inclusion were as follows: articles had to research (a) firms’ GS or GC or both and (b) examine the impact of GS and/or GC on firms’ economic performance. Papers were excluded according to the following criteria: (a) insufficient or misaligned focus on financial performance (five papers), (b) insufficient or misaligned focus on the impact of GS and GC on firms’ financial performance (seven papers), (c) unclear methodology (one paper), and (d) lack of reliable evidence (one paper).

The first author identified fifteen articles for further scrutiny during the full-text review. The two authors then individually re-evaluated those articles, reaching a consensus on including one and excluding the remaining fourteen. Articles that did not explicitly examine at least one of the thematic focal points listed in the exclusion criteria were excluded, leaving eighty-four articles for inclusion and fourteen excluded. Finally, the reference lists of all included articles were analysed through citation tracking (snowballing) to identify relevant grey literature (Haddaway et al., 2022). Through this approach we discovered seven grey literature articles on GS, but none on GC. Our final sample therefore comprised ninety-one publications. The entire process is set out in Fig. 2.

Risk of biasThis systematic literature review was conducted using a clear and well-documented process, manually selecting literature to minimise the risk of bias (Tranfield et al., 2003). We implemented several strategies to further reduce bias during the assessment of the articles included. Firstly, we searched multiple databases using inclusive search terms to ensure a comprehensive collection of articles. Secondly, we established specific criteria for data extraction, organising the information in an evidence-based table. Thirdly, the second author assessed a randomly selected number of articles at all screening stages. Finally, the authors iteratively and continuously discussed the potential limitations of this systematic review and how to mitigate them.

Preliminary analysis of included articlesThe most frequent publisher in this area of research was the journal Business Strategy and the Environment, which represented 12.1% or eleven articles in our dataset. The list of journals in Table 2 suggests a focus on environmental sustainability as well as the fields of economic development, innovation, and business ethics. Seventy-eight (85.7%) of the ninety-one studies were based on empirical research, seven (7.7%) were grey literature materials, four (4.4%) were review studies, one was theoretical, and one was a conceptual study. As for the geographical coverage of the studies included, we identified forty (43.9%) on developing countries, twenty-nine (27.6%) on developed countries, and seventeen (15.3%) on multiple mixed-country contexts. The detailed geographical focus of the literature as presented in Fig. 3 revealed geographic differences in the coverage of literature that are discussed in Section 4.2.

Frequency of articles per journal (grey literature excluded).

This section presents the findings of the systematic literature review in three main areas. First, using SLR as a comprehensive and transparent review process, we offer a framework that clarifies and refines the existing and commonly applied definitions of GS and GC in the literature. In Sections 3.1 to 3.3, we classify major groups of definitions for both GS and GC and describe the interrelation between these complex constructs (Awwad Al-Shammari et al., 2022). Secondly, in Section 3.4, we explore the discourse on the financial impact of GS and GC in firms, comprehensively mapping their ambivalent relationships and the connections between these constructs. Thirdly, in Section 3.5, we provide an in-depth evaluation of the variables and other factors influencing the relationship between GS and GC and their impact on firms’ financial performance (Martínez‐del‐Río et al., 2012).

Green skillsDuring the screening process, we identified ten peer-reviewed articles exploring the impact of GS on firms’ financial performance and eight others including both GS and GC in their exploration of financial impact. Additionally, we identified seven studies focused on GS that could be classified as grey literature through snowballing from references in peer-reviewed articles.

The prevailing concept of GS is relatively broad and ambiguous, making their precise nature unclear.5 The ambiguity is best illustrated by the wide range of terms and definitions describing GS. Terms used interchangeably include “green skills” (Strachan et al., 2022), “green competencies” (D’Souza et al., 2019), “green innovation skills” (Zhu et al., 2023), “environmental competencies” (Dzhengiz & Niesten, 2020), “environment skill(s)” (Darendeli et al., 2022; Foulon & Marsat, 2023; Mehrajunnisa et al., 2023), and “sustainable-oriented competencies” or “sustainable skills” (Ishaq et al., 2023), while the related term “green-collar workers”, as identified by Martinez-Fernandez et al. (2010) and the ILO (2011), refers to professionals, managers, and others with similar roles relating to GS in firms.

A commonly used definition of GS from Strietska-Ilina (2011, p. 103), quoted by Strachan et al. (2022), summarises GS as the “technical skills, knowledge, values, and attitudes needed in the workforce to develop and support sustainable social, economic, and environmental outcomes in business, industry, and the community”. While some GS definitions emphasise the impact of individuals' learned skills and knowledge on sustainability and the environment (Dzhengiz & Niesten, 2020; Strachan et al., 2022), others highlight the role of individuals’ inherent traits, values, and attitudes in achieving environmental and social development (Bozkurt & Stowell, 2016). In the realm of grey literature, three main arguments prevail and have shaped the definition of GS being used. First, green jobs are believed to require specialised GS (Bozkurt & Stowell, 2016; Cecere & Mazzanti, 2017; Darendeli et al., 2022; D’Souza et al., 2019; Gadomska-Lila et al., 2023). Second, and in contrast, others view GS as traditional skills applied in a green context rather than specific to green tasks (Strachan et al., 2022). The third perspective, aligning with the first, argues that the development of entirely new GS, such as sustainable materials knowledge, is necessary (CEDEFOP, 2011, 2012, 2018; Green Jobs Alliance, 2013; ILO, 2011; Martinez-Fernandez et al., 2010; OECD/CEDEFOP, 2014).

All the definitions of GS collated in Table 3 emphasise the common objective of GS as protecting the environment, conserving natural resources, and advancing a more equitable and environmentally sustainable economy and society. As a further step, we identified three specific areas of focus that the definitions of GS emphasise: (1) knowledge-based skills for sustainability and environmental impact, (2) competencies and traits influenced by social settings, and (3) social and environmental value and attitude-based green skills.

Green skills definitions conceptual focus.

| Reference | Quoted Definitions | Conceptual Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Strachan, S., Greig, A. & Jones, A. 2022. p.491 (Originally quoted from Strietska-Ilina, et al., 2012 (p.103) | “Green skills are broader still, referring to skills in the low carbon and environmental goods and services sector, as well as those needed to help all businesses transition to a low carbon and sustainable future.”“In the context of this research ‘green’ skills refer to all the knowledge, skills, competencies and attributes required in the workforce to support a low carbon transition to a cleaner, fairer economy and society or, more colloquially, ‘going green’ and, removes the association with particular. roles, functions or sectors.” (p103)“Green skills can be defined as ‘technical skills, knowledge, value, and attitude needed by green workers to perform tasks that contribute to sustainable environment, economy, and social development.” | Knowledge-based skills for sustainability and environmental impact |

| Dzhengiz, T. & Niesten, E. 2020. (p.887) | “(...) the knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviours and personal traits of individuals and managers that lead to the solution of complex environmental problems, and hence contribute to the achievement of a sustainable future.” | Knowledge-based skills for sustainability and environmental impact |

| D’souza et al., 2019. (p.312) (Originally quoted from Jones & Voorhees, 2002, p.7) | “Competence in sustainability is perceived as having acquired skills and knowledge to deal with problems, complexities and challenges and providing solutions through a balanced holistic approach that would not only benefit the organisation but also the environment. Competencies determine learning outcomes, and they are defined as “a combination of skills, abilities, and knowledge needed to perform a specific task.” | Knowledge-based skills for sustainability and environmental impact |

| Gadomska‐Lila, K., Sudolska, A. and Łapińska, J., 2023. (p.1154) | “(…) green competences as human qualities, skills, knowledge, abilities, and behaviours aimed at reducing energy consumption, protecting ecosystems and biodiversity, and minimizing emissions and waste.” | Knowledge-based skills for sustainability and environmental impact |

| Mirčetić, et al. 2022. (p.4) | “Natural green competencies: An individual’s underlying traits and personality dimensions, derived from observations and mentoring received at formative stages, regarding dominant green behaviour of their immediate social groups.”“Acquired green competencies: Green knowledge and skills that an individual accumulates through experience regarding environmental issues that lead to strong convictions and feelings about acting in an environmentally friendly manner.”“Effective green competencies: Combination of natural and acquired green competencies.” | Competencies and traits influenced by social settings |

| Bozkurt, Ö. & Stowell, A. 2016. (p.148) (Originally quoted from CEDEFOP, 2012, p.20; OECD, 2010, p.26) | “(…) the knowledge, abilities, values and attitudes needed to live in, develop and support a society which reduces the impact of human activity on the environment.” “ (…) specific skills required to adapt products, services or operations due to climate change adjustments, requirements or regulations.” | Social and environmental value and attitude-based green skills |

Knowledge-based skills for sustainability and environmental impact form a critical typology within the broader landscape of GS, distinguished by their grounding in specialised knowledge and understanding related to sustainability and environmental concerns. This category encompasses the technical expertise necessary to navigate the complexities of a green economy and drive environmentally sound practices. At its core, the typology draws upon “sustainability scholarship”, representing a high level of learning acquired through formal education, training, and continuous professional development (D’Souza et al., 2019, p. 311). However, this knowledge base is not limited to theoretical understanding. It includes “domain-specific” technical know-how, such as knowledge in renewable energy technologies, sustainable agriculture practices, circular economy principles, and environmental regulations (Dzhengiz & Niesten, 2020, p. 883; Pan et al., 2021). These knowledge-based GS apply individuals’ understanding in various professional contexts—including designing and implementing sustainable solutions, developing green products and services, and integrating environmental considerations—into decision-making processes (Gadomska-Lila et al., 2023). Even seemingly non-green skills, such as procurement and finance, are increasingly in demand for sustainable sourcing and green financing roles to support a broader green transition across all sectors (Strachan et al., 2022). Ultimately, the emphasis in this category is on a strong foundation of relevant knowledge as a prerequisite for effectively enacting and advancing GC in the workplace (Bozkurt & Stowell, 2016).

The second category, competencies and traits influenced by social settings, emphasises the crucial role of interpersonal dynamics in advancing environmental and societal goals. For us, “social settings” means the various interactions, relationships, and collaborations within and outside an organisation that shape an individual’s ability to contribute to their organisations’ GC. These skills differ from knowledge-based skills in that they focus not on a cognitive understanding of environmental issues, but on the ability to effectively engage and interact with others in ways that promote green business outcomes (Trujillo-Gallego et al., 2022). Key examples are effective stakeholder management and communication skills. Stakeholder management skills focus on actively engaging stakeholders, understanding and prioritising their environmental and social concerns (Aftab et al., 2023), and fostering positive relationships (Chua et al., 2023). Communication skills allow effective interaction among individuals and teams, crucial for sharing best practices, disseminating environmental goals, disclosing environmental data, and enhancing teamwork (Albertini, 2019; Álvarez‐García et al., 2022). These skills are also necessary for effective leadership to pursue organisational sustainability (Álvarez‐García et al., 2022). The influence of social settings on these competencies is thus evident in how they are acquired and applied. While underlying knowledge is undoubtedly involved, the development of these GS is heavily shaped by external influences and active information seeking (Dzhengiz & Niesten, 2020).

The third category of GS, namely social and environmental value and attitude-based green skills, foregrounds values and attitudes for improving society and the environment. It highlights how personal beliefs and ethical viewpoints are crucial in motivating the development of GS (Mirčetić et al., 2022; Strachan et al., 2022). As Mehrajunnisa et al. (2023) note, personal morals, values, collective consciousness, ethics, cultures, and customs are key drivers of environmental orientation and employees’ organisational green behaviour. Developing these GS within an organisation introduces and reinforces new values, fostering a sustainable corporate culture (Gadomska-Lila et al., 2023). This is particularly evident in leadership, where managers with strong environmental values and attitudes are more inclined to perceive environmental issues as opportunities and proactively initiate environmental decision-making (Dzhengiz & Niesten, 2020). Consequently, Ling (2019) emphasises the need for top management to cultivate a mission statement and shared values that actively promote environmental advocacy. Such leadership commitment can enhance environmental knowledge and confidence among organisational members, enhance the quality and quantity of environmental outcomes, and drive societal and environmental transformation (Dzhengiz & Niesten, 2020). Ultimately, these deeply held values and attitudes directly influence how employees think, learn, and act in relation to environmental and societal considerations.

It is worth emphasising that the academic literature approaches GS taking into account the context in which they are embedded. The relevance and effectiveness of skills are linked to their practical use in addressing environmental challenges, enhancing their contribution to sustainable performance, and accomplishing long-term goals or visions (Mehrajunnisa et al., 2023; Mirčetić et al., 2022). Hence, GS are widely understood with a degree of flexibility, reflecting the sustainability needs and activities of particular firms. For instance, individuals in carbon-intensive or brown sectors can support their firms’ sustainable transition by translating their generic skills, such as autonomy or decision-making, to more sustainability-oriented skills, such as resource-efficient production (Strachan et al., 2022). Similarly, individuals with strong problem-solving skills can address intricate sustainability challenges by employing a balanced, systematic, and holistic approach, devising environmentally conscious and economically advantageous solutions for organisations (D’Souza et al., 2019; Dzhengiz & Niesten, 2020).

While the grey literature acknowledges the significance of GS for advancing green transitions at the firm level, it frequently conflates GS with green jobs, a tendency also observed in some academic research. Green jobs foster sustainability and reduce environmental impact, with increasing demand in sectors such as offshore wind, green car manufacturing, and other fields related to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) (Bozkurt & Stowell, 2016). The significance of these individuals’ skills is recognised in the emphasis given to the rising need for skilled workers, managers, engineers, and scientists to be employed in green jobs in order for a successful green transition to be achieved (CEDEFOP, 2012). Some studies claim that the success of these jobs depends on a workforce equipped with appropriate GS, which boost firm competitiveness, drive innovations, and lower production costs; thus, GS act as “integrated pillars” of green innovation (Bozkurt & Stowell, 2016; Cecere & Mazzanti, 2017, p. 88). In this context, GS are not only central to performing green jobs but are also intrinsically related to achieving a successful green transition, as they are essential for driving both job effectiveness and green innovation (Gadomska‐Lila et al., 2023; Mehrajunnisa et al., 2023). The literature points to the importance of policymaking in the context of GS as the labour market faces persistent skills mismatches and shortages (Bozkurt & Stowell, 2016). The challenges associated with GS shortages include risks of high unemployment, low returns on training investments, and missed job creation opportunities (Nikolajenko-Skarbalė et al., 2021). This underscores the need for practical measures such as employee training, education, and policy initiatives that can encourage these GS development opportunities (Green Jobs Alliance, 2013). Despite the increasing demand, GS-focused policies are scarce and often integrated into broader environmental policies instead of receiving dedicated policy attention (CEDEFOP, 2011).

Green capabilitiesThe academic discourse on GC has grown considerably over the past two decades, recognising their critical role in shaping various organisational outcomes. The findings in the literature on GC contribute to our understanding of their significant role in achieving organisational success and improving financial performance (Lin et al., 2019).

Sixty-six (72%) out of ninety-one studies included in this systematic review focused on the discourse surrounding GC, emphasising a predominant emphasis of GC over GS in the literature. Like GS, GC are described using various terms, including but not limited to “green capability” (Chiu & Hsieh, 2016; Gupta & Zhang, 2020), “green organisational capability” (Xing et al., 2020), “environmental capability” (Dzhengiz & Niesten, 2020), “sustainability capability”, “business sustainability capability”, “environmental competence” (Wong & Ngai, 2021), “strategic green capability” (Shaharudin et al., 2023), and “sustainability-oriented dynamic capability” (Oliveira-Dias et al., 2022). It is also worth noting the presence of narrower and more specific terms used to refer to GC, including but not limited to variations of “green innovation” such as “green product innovation” (Zhu et al., 2023) and “green technology innovation” (Zhang et al., 2023a), “green political capability” and “green supply chain management capability” (Yi & Demirel, 2023), “green process capability” (Shaharudin et al., 2023), “green operational capability” and “green creativity” (Nguyen et al., 2023), “green entrepreneurial orientation”, “green purchasing”, “green design”, “green knowledge transfer”, “green marketing”, and “green integration capabilities” (Marzouk & El Ebrashi, 2023).

Unlike GS, which are defined at the level of the individual employee, GC are attributed to the organisational capabilities at the firm level. Dzhengiz and Niesten (2020, p. 889) define GC as “an organisation’s abilities to either reduce the damage to or create benefits for the natural environment while managing the tensions between environmental and economic bottom lines”. Similarly, Khan et al. (2023b) define GC as an organisation’s ability to utilise its existing resources and expertise to augment its capacity and adapt to dynamic sustainability challenges in the market. Both definitions emphasise the utilisation of existing resources and expertise to improve environmental and economic organisational performance. Table 4 summarises the definitions of green capability used in the literature. These definitions are classified under three distinct focus areas, namely (1) green dynamic and adaptive capabilities, (2) sustainability integration capabilities, and (3) forward-looking strategic planning capabilities.

Green capabilities definitions conceptual focus.

| Reference | Quoted Definitions | Conceptual Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Li, 2022. (p.3) | "(...) green dynamic capability is the deepening and continuation of the concept of dynamic capability. Green dynamic capability is the high-level capability of enterprises to achieve sustainable and green development in the everchanging market environment. In the process of green innovation, resource-based enterprises combine valuable, unique, integrated, and dynamic capabilities. Such capability combination is referred to as green dynamic capability." | Green dynamic and adaptive capabilities |

| Xing, X., Liu, T., Shen, L. & Wang, J. 2020. (p.4) | "(…) the capability of firms to develop their green organizational capability to respond to market changes by using existing resources and a range of knowledge renewal activities." | Green dynamic and adaptive capabilities |

| Kuo-Chung, S., Shio-Yu, C., Kung-Don, Y. & Hsin-Yi, Y. 2019. (p.38, 42-43) | "(...) the abilities of a firm to exploit its existing resources and knowledge to renew and develop its green organizational capabilities to react to the dynamic market”"(...) the ability of a company to exploit its existing resources and knowledge to renew and develop its green organisational capabilities to react to the dynamic market." | Green dynamic and adaptive capabilities |

| Wong, D. T. W. & Ngai, E. W. T. 2021 (p.441&446) | "(...) defined sustainability competence as the competence to deal with future plans, predictions, and expectations, with a forward-looking perspective to deal with uncertainty." | Forward-looking and strategic planning capabilities |

| Dzhengiz, T. & Niesten, E. 2020. (p.889) | "(…) a firm’s [abilities] to carry out its productive activities in ways that limit damage to the natural environment.”"(…) a firm’s environmental capabilities are those that allow it to reduce its ecological footprint.” | Forward-looking and strategic planning capabilities |

| Baranova, P. & Paterson, F. 2017. (p.838) | "(...) firm’s environmental capabilities are those capabilities that allow a firm to reduce its ecological footprint.""These capabilities include, for instance, environmental management skills and routines, product/service design with a focus on sustainability, waste management, resource efficiency skills and practices and others that focus on the reduction of the ecological footprint of the firm." | Forward-looking and strategic planning capabilities |

| Khan, S. A. R., YU, Z. & Farooq, K. 2023b. (p.2024) | "Green capabilities refer to organizational capacity that leverages current resources and expertise to grow its skill to adapt to dynamic markets challenges." | Forward-looking and strategic planning capabilities |

| . (p.441&446) | "Sustainability capability in manufacturing can be defined as the ability to combine manufacturing practice with operational practices in design, distribution, use, product service, and governance for innovative and marketable combinations of services and products that contribute to sustainability." "Business sustainability capability is the information required by an enterprise to integrate essential capabilities and flexibility into future architecture; meanwhile, a firm’s sustainable business management must meet the requirements of stakeholders in different economic, environmental, and organizational positions within the network." "Environmental competence is defined as a firm’s ability to use corporate environmental practices to facilitate business sustainability, in a situation where economic competitiveness and environmental protection are increasingly intertwined." | Sustainability integration capabilities |

The first category focuses on the dynamic and adaptive capabilities for sustainability that enable organisations to respond effectively to constant changes in market conditions, especially in the context of the developing climate change and sustainability agenda (Huang et al., 2023). Definitions of capabilities that focus on integrating sustainability into business practices for performance enhancement describe an organisation’s ability to effectively embed sustainability principles and practices into its core business operations and across its value chain, and fall into the second category. This category encompasses an organisation’s capability to combine operational practices with sustainability considerations in design, production, distribution, and governance areas, to name just a few. By integrating environmental and social factors into organisational capabilities, firms can meet diverse stakeholder needs and leverage sustainable practices to enhance business performance and achieve sustainable operations (Zhang et al., 2023b). Finally, in the third category, definitions emphasising forward-looking and strategic planning capabilities emphasise the ability to anticipate future sustainability trends and uncertainties, integrate long-term sustainability goals into strategic planning, and develop organisational skills and routines to proactively reduce environmental impact (Baranova & Paterson, 2017; Khan et al., 2023b). These capabilities encompass a future-oriented approach navigating the complexities of a net-zero transition, enabling firms to adapt to dynamic markets and implement strategic actions like environmental management, sustainable design, and resource efficiency, ultimately fostering long-term sustainability (Shaharudin et al., 2023; Wong & Ngai, 2021).

The literature views GC as intrinsically linked to three distinct theories, namely absorptive capacity (AC) (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990) and dynamic capability (Teece et al., 1997), as well as the related work on recombinant capabilities (Carnabuci & Operti, 2013; Zhu et al., 2023). AC refers to a firm’s ability to identify, assimilate, and apply new external knowledge (Zhang et al., 2023b). Green absorptive capacity (GAC) is the capability of a firm to acquire, integrate, modify, and utilise environmental knowledge (Chen et al., 2015). GAC is essential for developing GC because it enables firms to incorporate sustainable practices and innovations from external resources (Marzouk & El Ebrashi, 2023). Dynamic capabilities (DC) build on the ability to integrate, reconfigure, and transform internal and external capabilities, allowing firms to respond effectively to rapidly changing market conditions (Zhu et al., 2023). Green DC (GDC) aim to leverage a firm’s existing and newly acquired resources and knowledge to innovate and strengthen its GC in response to dynamic market environments (Li et al., 2023b). Several definitions of GC underscore the integration and reconfiguration of resources building on the ideas of DC and AC. For instance, Dangelico et al. (2017) and Waqas et al. (2022) emphasise the necessity of resource integration to achieve environmental goals. Similarly, Xing et al. (2020) and Baranova and Paterson (2017) highlight the importance of reconfiguring resources to respond to dynamic market changes related to sustainability. This discourse underlines the complexity inherent in developing and sustaining green and sustainable business practices by bridging internal and external knowledge in a dynamic process (Carnabuci & Operti, 2013).

As an extension to DC, the recombinant capabilities6 of firms play an important role in enabling them to develop new and effective GC by recombining existing knowledge resources across different domains, increasing knowledge diversity and absorption (Xing et al., 2020). Nguyen et al. (2023) suggest that firms’ recombination activities are vital in developing green organisational capabilities, integrating green operational capability, green dynamic capability, and green creativity. Therefore, recombinant capabilities are particularly prominent in fostering firms’ green innovations (Li, 2022).

In the realm of GC literature and the discourse of innovation, green innovation and its impact merit special attention, evidenced by their prominent coverage in research.7Liboni et al. (2023, p. 1135, citing Wong, 2012) define “green innovation” as “firm innovativeness in developing environmentally responsible products/services and adopting new environmental practices”. Green innovation capabilities are viewed as prominent enablers of other green capability development within firms. For instance, green innovation capabilities are thought to enable firms’ green supply chain management (GSCM) capability (Asamoah et al., 2023), green purchasing capabilities (Khan et al., 2023b), green marketing capabilities (Li et al., 2023a), and even green collaboration capabilities (Khurana et al., 2022). Furthermore, green innovation capability is particularly important in delivering, integrating, and embracing valuable new green knowledge and shaping organisational green knowledge management capability development (Chua et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2023). Consequently, green innovation capabilities lead to green patents, products, and services, resulting in a competitive advantage for innovating firms (Ishaq et al., 2023; Marín-Vinuesa et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2021).

The relationship between green skills and green capabilitiesThe relationship between GS and GC is rarely explicitly discussed in the literature. Indeed, only eight out of the ninety-one studies included in this review discuss or examine GS and GC jointly. One strand of the literature views GS as the foundation for building GC (Mehrajunnisa et al., 2023). In this perspective, employees are vital stakeholders in influencing organisational culture (Aftab et al., 2023) and catalysing environmental innovation (Albertini, 2019). The discourse around managers’ GS is key to enabling effective firm-level GC, such as producing green products, services, and processes (Dzhengiz & Niesten, 2020). The literature also often highlights the importance of firms supporting employees with continuous learning and training opportunities to develop GC that result in positive economic outcomes (Albertini, 2019). Honing employees’ environmental understanding, competencies, and skills can help firms effectively tackle environmental challenges and drive firms’ sustainable performance internally (Khan et al., 2023a). This further emphasises the need to strengthen green intellectual capital embedded within the employees of an organisation to ensure that strong firm-level GC are present (Chen, 2008).

A slightly different approach, however, views GC as the source of the GS generated in the firm. For example, the literature frequently emphasises the critical role of firms in supporting their employees (Mehrajunnisa et al., 2023). Fostering a robust corporate environmental ethos aligns employee conduct with green goals, stimulating a sense of attachment and dedication to nurturing organisational GC (Khurana et al., 2022). Developing a nurturing organisational culture that fosters a shared vision (Journeault, 2016) boosts the sustainability objectives of individuals (Dao et al., 2011) and promotes high work involvement practices, which are vital for achieving positive environmental and financial performance outcomes in a firm (Martínez‐del‐Río et al., 2012). A prominent example of this is green human resource management (GHRM), which involves the active engagement of firms in their employees’ green competence building, orientation, motivation, and employee involvement (Awwad Al-Shammari et al., 2022; Mehrajunnisa et al., 2023; Trujillo-Gallego et al., 2022; Zhu & Yang, 2021). The GHRM of a firm can enable such outcomes by providing continuous learning and training opportunities, thereby strengthening green intellectual capital (Chen, 2008). These findings suggest a complex, mutually reinforcing relationship between GS and GC. A more detailed examination is undertaken in Section 4.3, where we illustrate their co-evolution and mutual reinforcement.

The impact of green skills and green capabilities on firms’ financial performanceAs part of the systematic review process, forty-two financial performance metrics were extracted from the literature that examines the impact of GS and GC on firm performance. These metrics were then inductively coded into six main performance categories, including (1) costs, (2) profitability, (3) efficiency and productivity, (4) firm growth, (5) liquidity, and (6) market performance (see Table A.1 in the Appendix). This coding process was developed through the thematic grouping of similar financial indicators across the reviewed literature.

First, each financial performance metric was coded verbatim, utilising the exact terminology from the analysed literature, and described independently, with each of the forty-two metrics treated as a separate unit of analysis. Then, thematic similarities were identified inductively. For example, indicators related to cost savings, cost control, and the avoidance of penalty and fine costs were grouped under “costs”, while those measuring sales and revenue growth were grouped under “growth”. The grouping process was conducted by the lead author, who regularly consulted with the second author to improve interpretive validity (Maxwell, 1992). When differences occurred in coding, these were discussed and resolved through investigations of broader financial literature and final consensus.

While some overlaps unavoidably exist among the six categories (e.g., profitability and growth), each category reflects a conceptually distinct dimension of financial performance as reported in the literature. This categorisation also aligns well with the widely accepted domains in financial and strategic management literature (e.g. Kaplan & Norton, 1996; Palepu et al., 2020), although it was not directly drawn from a single existing framework. Instead, we aimed to offer an integrated and literature-informed structure that enabled meaningful comparison across studies while maintaining fidelity to the specific indicators accounted for. In what follows, we discuss the literature classified according to the financial performance metric of focus.

Impact on costsThe literature most frequently highlights the impact of GS and GC on costs, as costs are an important stand-alone financial metric and form an inherent part of other performance indicators such as profits. A strong research focus revealed in the literature was the highlighting of organisational adaptations in response to environmental challenges, which reduce costs, improve efficiency and productivity, and increase profitability, aiding organisational growth (Asamoah et al., 2023; Dao et al., 2011; Li et al., 2023b; Martinez-Del-Rio et al., 2012).

For example, the sub-typologies of GC, such as the pollution prevention capability, frequently lead to cost savings for firms (Durge & Sangle, 2020). Through behavioural and material changes introduced as part of pollution prevention, firms can reduce waste and cost while improving efficiency and productivity (Albertini, 2019). Other GC such as green procurement, manufacturing, and waste treatment capabilities are identified in the literature as making cost savings by avoiding negative outcomes such as environmental law enforcement penalties and reputational shocks resulting from unsustainable behaviour (Foulon & Marsat, 2023; Yi & Demirel, 2023). Additionally, organisations can save costs by utilising their green collaboration capability, which, according to Khurana et al. (2022), guides firms to effectively navigate and leverage government initiatives, thereby maximising the benefits of available tax incentives.

Individuals’ GS complement these organisational GC by promoting environmental changes internally and saving costs for the firm by increasing firm-level regulatory compliance and improving reputation (Tarifa-Fernández et al., 2023). The GS of employees can also lead to significant cost savings by influencing organisations to advance technology that reduces resource use, improves product quality with safer materials, minimises packaging, increases recycling, and enhances innovation practices (Baeshen et al., 2021; Pan et al., 2021). Although GS mean high initial costs for businesses, they have been found to result in long-term savings, especially following effective implementations (Trujillo-Gallego et al., 2022).

Impact on profitabilityThe NRBV of firms suggests that a competitive advantage drives positive organisational profitability gained through enhanced environmental strategies and resources (Hart, 1995). As a result, many articles have measured the profitability implications of firms acquiring, combining, and rearranging GS and GC to respond to customer, stakeholder, and governmental demands (Ali et al., 2020; Darendeli et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023a).

For example, by developing organisational green product innovation capabilities, firms can experience higher customer satisfaction while reducing the financial risks that arise from regulatory violations and securing organisational profitability (Gangi, 2023, p. 2; Zulkiffli et al., 2022). Additionally, GSCM capabilities can improve organisational performance and enhance gross profit margins in highly dynamic markets by increasing operational efficiency and regulatory compliance (Chua et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023b). Big data analytics capability further enhances regulatory compliance by enabling firms to absorb information more effectively, thus avoiding fines, improving efficiency, and boosting profitability (Ali et al., 2020; Zhu & Yang, 2021). Similarly, logistics 4.0 capabilities enable organisations to make better use of their green strategic resources, such as their green dynamic capabilities, to enhance firm responsiveness and make better strategic decisions, which can improve prompt delivery to customers and thus lead to improved levels of profit margins (Bag et al., 2020).

Evidence, although limited to only two studies, indicates that investments in GS positively affect profitability metrics such as return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), and net profit margins. Darendeli et al. (2022) found that firms with a higher concentration of GS employees experience increased future profitability, including higher ROA and net profit margins. However, these firms also face higher costs due to increased salaries for skilled employees. Additionally, Kuo-Chung et al. (2019) found that GS are crucial for green innovation capabilities, indirectly enhancing green dynamic capabilities and subsequently improving ROE, ROA, and net profit.

Impact on efficiency and productivityEfficiency in a firm is a complex system, measured by costs, revenues, and profit levels, which improves organisational market position (Nguyen et al., 2023). Similarly, productivity is a reflection of the firm’s outputs in proportion to the inputs (Wang et al., 2021). Consequently, efficiency and productivity are important metrics of firms’ financial performance, particularly influenced by costs. Evidence suggests that green dynamic capabilities boost organisations’adaptability and flexibility in green practices, directly impacting operational efficiency and productivity and driving financial performance through efficient resource use and regulatory compliance (Liboni et al., 2023; Tarifa-Fernández et al., 2023). Employees’ GS, on the other hand (e.g., consciousness, employee knowledge, abilities, attitudes, and behaviours), reinforce organisational capabilities and foster the employee’s ability to identify sustainability challenges and opportunities for organisational action, thereby creating opportunities to increase labour productivity and performance (Gadomska‐Lila et al., 2023, p. 1155; Strachan et al., 2022). Boosted by GDC and GS, organisational green practices such as the sustainable production of goods or provision of services, green innovation, organisational GSCM, and green logistics can lead to the more effective use of resources, driving productivity and efficiency and ensuring long-term success and competitive advantage (Asamoah et al., 2023; Ishaq et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023b; Mady et al., 2023; Nguyen et al., 2023; Shaharudin et al., 2023; Trujillo-Gallego et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2023).

Impact on firm growthFirm growth can be measured using the change over time in different firm size indicators, including firm revenues and sales (Durge & Sangle, 2020; Marín-Vinuesa et al., 2020), market share growth, and new market entry (Chen et al., 2015; Mady et al., 2023), as well as employment growth (Wang et al., 2021). According to both the resource-based and natural-resource-based theories, organisational resources play a significant role in seizing growth opportunities and securing a competitive advantage in highly dynamic markets (Barney, 1991; Hart, 1995). Therefore, GS and GC are expected to have a positive impact on firm growth.

The literature indicates that GS and GC are key drivers of firm growth, particularly in advancing firms’ sales revenue and market share (Ishaq et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023a; Zhu et al., 2023). GC, including those related to green management and innovation, enable firms to align with market demands and improve financial performance by retaining existing customers, increasing a firm’s market penetration and balancing economic development with green innovation practices (Bag et al., 2020; Xing et al., 2020). For instance, effective green entrepreneurial orientation and green insight capabilities coupled with green innovation capabilities enable firms to identify and explore new business opportunities, securing future growth through innovative and strategic decision-making (Ishaq et al., 2023; Li, 2022).

While GC are acknowledged for their potential to enhance firm growth, the evidence linking green skills to enhanced firm growth is scarce. The study by Mirčetić et al. (2022) is the sole article in our dataset to detail the significance of employees’ GS in overcoming contemporary challenges in creative and knowledgeable ways to improve green performance and secure long-term growth. Therefore, we note a significant gap in the current research, underlining the need for further investigation into how GS impact firm growth.

Impact on liquidityOur findings reveal that distinct GC support financial liquidity and stability, thereby improving a firm’s financial health significantly. The literature finds that GC (e.g., green purchasing capabilities and green dynamic capabilities) are key to improving a firm’s current ratio, which is measured as the ratio of current assets to revenue, representing organisational turnover and the overall strength of firm liquidity, and simultaneously reflecting the firm’s ability to transform (Nguyen et al 2023; Yee et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2023a). Enhancing operational efficiency, optimising resource allocation, and integrating effective green technology significantly improve a short-term liquidity position, as reflected in the current ratio (Zhang et al., 2023a). Green product innovations significantly improve capital by boosting sales through attracting environmentally conscious consumers and entering new markets (Ling, 2019). This revenue growth boosts cash inflows, thereby increasing working capital. Additionally, by streamlining production processes and improving supply chain management through green innovations, firms can reduce current liabilities, contributing to a more favourable working capital position (Gangi et al., 2023).Similarly, by enhancing a firm’s reputation, improving risk management, increasing access to additional resources, demonstrating a commitment to innovation and sustainability, and fostering stronger relationships with financial partners, green collaboration capabilities significantly contribute to improved creditworthiness and more favourable credit terms from financial institutions (Khurana et al., 2022).

Our literature review found no evidence of studies investigating the relationship between GS and their impact on firms’ liquidity.

Impact on market performanceFinally, we identified in the literature three key metrics—earnings per share (EPS), dividend yield, and market value—as measures of market performance.8 Evidence indicates that GS impact EPS and dividend yield (Kuo-Chung et al., 2019), while the literature suggests a positive link between firms’ GC, such as environmental management capabilities, and market value (Dangelico et al., 2017). Accordingly, studies find that green human capital embedded in GS boosts EPS by enabling the implementation of green strategies and innovations, which amplifies revenues and reduces costs (Kuo-Chung et al., 2019). Similarly, firms investing in GS generally show higher dividend yields, as these skills contribute to profitability and financial stability, leading to more substantial dividends and increased investor confidence (Darendeli et al., 2022). Additionally, the literature suggests a significant positive link between organisational green innovation capability and firms’ market performance (Nguyen et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2022; Waqas et al., 2022). At the same time, green innovation capability also positively mediates the relationship between sustainability-oriented dynamic capabilities and market performance. Green innovation capability is measured by organisations’ product output, which improves market performance by creating innovative new products which support greater financial values and thus deliver enhanced success rates and return on investment (Dangelico et al., 2017).

Our SLR suggests a significant positive relationship between GS and GC and organisational financial performance across the six measures discussed above, because firms can reduce costs, enhance organisational profitability, and improve efficiency and productivity by fostering a green-oriented, sustainable, dynamic, and innovative approach while ensuring compliance with environmental regulations and stakeholder and customer demands.

The factors that influence the impact of GS and GC on firm performanceThe key focus across all selected studies in this SLR was on whether organisations could reap financial returns from GS and GC. While there is consensus on the broad positive impact of GS and GC on firm performance, several caveats were identified as significant influences on this important relationship. Below, we discuss the most frequently recurring caveats reported in the literature.

Firm size and ownershipFirm size differences between studies often impact the generalisability of research findings. In our dataset, SMEs are the most frequently represented, followed by large corporations, family businesses, and startups. The discourse regarding the role of SMEs in economic and environmental impact is twofold. On one hand, SMEs are considered essential to any economy due to their contributions to the gross domestic product (GDP) and in facilitating jobs (Khan et al., 2023a). On the other hand, SMEs are responsible for up to 70% of total industrial pollution per annum globally and simultaneously face significant sustainability, economic, and social issues, including the rising cost of energy and materials and the lack of skilled workforce or orientation (Mady et al., 2023, p. 1). In the case of developing countries, SMEs represent about 90% of organisations, contribute over 40% of GDP and generate over 50% of total jobs (Ishaq et al., 2023, p. 1515). However, despite their substantial impact, SMEs still go undetected within the sustainability domain due to their small size, especially in developing countries where governmental policies addressing economic and environmental issues may be limited in their effect (Ishaq et al., 2023). In investigating the differences between small and large firms, Baeshen et al. (2021) argue that large firms are more likely to implement environmentally friendly practices compared to small firms since they have the necessary resources and infrastructure to engage in greening processes and the required complementary assets (e.g. intellectual property protection, logistical capabilities) to reap the financial performance benefits from their sustainability efforts. Khurana et al. (2022) support this by suggesting that micro, small and medium-sized enterprises lack sufficient funds to invest in their employees’ GS and thus lag behind in their capability development. In another study comparing SMEs and large organisations, Wong and Ngai (2021, p. 446) further note that in large organisations, GC are driven by top management to enhance sustainability practices. They argue that such practices are often more complex due to large firms’ emphasis on process innovation and product development, unlike smaller firms with simpler business settings that mostly focus on product development. Larger corporations also hesitate to introduce new green products for fear of their existing products being “cannibalised”, resulting in the loss of their customer base (Marzouk & El Ebrashi, 2023, p. 9). Hence (Baeshen et al., 2021, pp. 5, cited in Vossen, 1998) emphasise that “the relative strength of small firms is primarily determined by their entrepreneurial dynamism, flexibility, efficiency, proximity to the market, and motivation”, suggesting that SMEs also have certain advantages in the space of organisational green skill and capability development.

Often overlapping with the SME category, family businesses present another caveat when attempting to understand the relationship between GS and GC on one hand and firm performance on the other. Family businesses, due to their flatter hierarchies and the absence of external shareholders, may have greater flexibility to align their decision-making with sustainability objectives, enabling more effective implementation of GS and GC (Tiberius et al., 2021). However, paternalism and inertia, commonly observed in family firms, are important challenges to sustainability implementation in these firms (Tiberius et al., 2021, p. 3). Therefore, they may be less likely to adopt GS and GC at the required levels, resulting in lower financial returns. Startups, again overlapping to a significant extent with the SME category, share similar struggles in striving to improve their market share and gain competitive advantage, thanks to their limited resources (Zhu et al., 2023).

Compared to family firms, startups face higher failure rates and are constantly under pressure to establish robust routines by developing their GS and GC to ensure long-term survival and sustained competitive advantage, especially as customer demand for sustainability increases (Oliveira-Dias et al., 2022). Consequently, startups gain relevance for sustainable development when they promote innovative solutions and better working conditions, effectively capitalising on environmentally relevant market failures, viewing them as opportunities to achieve profitability and generate sustainable value (Oliveira-Dias et al., 2022). These small, newly established businesses are thus more inclined to experiment with innovative approaches and play a significant role in transforming industries towards sustainable development, even inspiring larger organisations to adopt their sustainable initiatives (Dangelico et al., 2017).

Future research on GS and GCs should consider the diverse contexts involving firm size distribution, and also aim to better understand the subtypes of SMEs, including micro, small, and medium-sized firms, as well as family firms and start-ups.

Sectoral contextMuch of the literature identified in this study relates to the manufacturing sector in a range of country settings. Among the ninety-one studies, thirty-five present detailed findings from manufacturing firms, twenty-nine cover multiple sectors, and the rest examine various other sectors. The researchers most probably selected manufacturing sectors owing to their highly visible environmental impacts and the fact that they face more stringent environmental regulations (Khan et al., 2023b, p. 2023). Revolving around the production of goods, the literature often highlights the importance of greening firm processes and focusing on GS and GC that enable the reduction (Trentin et al., 2015), reuse (Singh et al., 2022) recycling (Waqas et al., 2022), repair (Zhang et al., 2023a), and closed-loop production (Shaharudin et al., 2023) of materials and products. However, there is a lack of scholarly attention to the service sector firms (i.e., retail, hospitality, and finance),9 despite their significant economic and environmental impacts. While our review has identified some existing research on sustainability within key service sectors, it also reveals a lack of emphasis on service industries whose environmental impact is less visible to the public and regulators (Dao et al., 2011; Oliveira-Dias et al., 2022). For instance, the finance sector’s growing commitment to sustainability could be improved by a deeper understanding of how to effectively leverage big data and green HR practices for environmental governance (Ali et al., 2020). Similarly, ICT and logistics sectors deserve more attention with respect to their growing environmental impact and the role of GS and GC as enablers to reduce this impact (Mady et al., 2023). As the size and environmental impact of the service sector become more visible, particularly its impact on energy and water sources, more research and insights are needed to better understand GS, GC and their relationship with firm performance in service firms.

Governmental settingsThe literature frequently emphasises the role of government as a critical factor in shaping organisational decision-making, particularly in driving the development of GS and GC. International differences in environmental regulations and compliance are paramount in understanding how firms adopt GS and GC (Yi & Demirel, 2023). Additionally, according to Khurana et al. (2022), effective government leadership is crucial for advancing sustainable innovations, including expanding organisational resources such as GS and GC. They assert that when governments back sustainable initiatives, lower pollution levels and greater business profitability can result. Furthermore, stricter regulations in certain countries, propelled by the escalating visibility and governmental acknowledgement of the climate crisis, often lead to harsher penalties for non-compliance, driving firms to expedite the greening of their skills, products, processes, and capabilities (Khan et al., 2023b). Such regulatory differences create varied pressures on organisations. Firms operating under more rigorous frameworks are driven to innovate and adopt green practices earlier than firms in less regulated markets (Xing et al., 2020). For example, organisations subject to higher environmental taxes or strict sustainability standards are more likely to develop GS and GC, leading to greater operational efficiency and cost savings, and ultimately driving improved firm performance (Pereira-Moliner et al., 2015).

Conversely, in regions and contexts where regulations are lax, the lack of government guidance can hinder greening initiatives and the development of GS and GC (Baranova & Paterson, 2017). A lack of stringent environmental regulation is also likely to weaken the impact of GS and GC on firm performance (Li et al., 2023a). Future research should explore how varying regulatory environments across countries affect the effectiveness of GS and GC in driving the financial success of firms.

Discussions and conclusionsThis SLR extends the scholarly understanding of how organisational sustainability affects firms’ financial performance by providing in-depth insights into the understanding of GS and GC, their interrelationship, and their impact on firms’ financial performance. First, our findings highlight the relatively scant attention to GS compared to GC in the literature and call for more emphasis on better understanding what GS involve for firms in different contexts and how they affect the performance of firms. Second, the study reconciles existing definitions of GS and GC into representative categories, providing a foundation for future researchers to develop and propose clarification surrounding these complex concepts. Thirdly, we analyse the findings of the literature relating to the impact of GS and GC on firms’ financial performance, inductively identifying six major financial performance-indicating groups with forty-two financial performance metrics from the literature. In doing so, we extract the main trends and factors that shape this relationship. The literature uses a multitude of complex constructs and proxies to explore how GS and GC affect firms’ financial performance across varying sample sizes and sectoral and geographical contexts, relying on a wide range of methods with different forms of data collection and analysis, mostly in cross-sectional datasets, with a small number of longitudinal datasets. Given this complexity and fragmentation, insights emerging from this study shed light on how best to reconcile the diverse findings from this literature and how to proceed with future research. Our main observations regarding the study’s findings are discussed below.

Proliferation of definitionsAs discussed in the findings section, the literature presents a wide range of definitions for GS and GC that do not overlap much with those in previous studies, resulting in a fragmentation in the literature on GS and GC. That being so, one of the main motivations of this study was to provide an up-to-date overview that could assist future research in consolidating terminology for the consistent development of scientific enquiry in this area. In particular, attempts to operationalise the concept of GS and the numerous issues related to their broad identification, measurability, and classification are complicated by the context-dependent nature of GS. Multiple studies assert that the broadness of the GS definitions ensures that all relevant skills are included in the analysis, removing restrictions tied to specific roles, functions, or sectors. Just as in the case of GS, our investigations showed widespread academic engagement with an extensive list of GC definitions in the literature that lacked significant overlap across the various studies. This proliferation of definitions, while it added richness to our understanding of GS and GC, did create challenges to any understanding of the major financial implications of developing GS and GC in firms.

To address this complexity in the literature, we propose a more systematic classification of GS and GC to assist future researchers interested in investigating the implications of different GS and GC on firm performance. To help better organise future research in this area, we have proposed for GS the broad categories of (1) knowledge-based skills for sustainability and environmental impact, (2) competencies and traits influenced by social settings, and (3) values and attitudes for societal and environmental development for GS. For GC, the broad categories we put forward are (1) dynamic and adaptive capabilities for sustainable development, (2) sustainability integration capabilities for improved performance and (3) forward-looking strategic planning capabilities.

Geographical contextGlobally, greenhouse gas emissions have increased dramatically, from 32.7 billion tonnes in 1980 to 53.85 billion tonnes in 2022 (Jones et al., 2024). This rise has been particularly pronounced in developing countries, driven by globalisation, population growth, increased consumption, and rapid industrialisation, resulting in firms facing intense pressures from market competition and environmental regulations (Durge & Sangle, 2020). The literature on GS and GC reflects these growing pressures on developing countries For instance, China stands out in our work as a recurring geographical context, in fourteen articles out of the ninety-one included (Huang et al., 2023; Waqas et al., 2022). Alongside China, countries like Malaysia and Pakistan feature prominently, reflecting the environmental challenges and opportunities firms in these developing contexts face (Foo, 2021; Ishaq et al., 2023; Khan et al., 2023a; Yee et al., 2021).

The geographical context significantly shapes the development and implementation of GS and GC. In developing countries, firms face economic pressures for immediate survival and competitiveness, as well as the need to innovate and adopt green practices to comply with increasing environmental regulations, mitigating risks (Zulkiffli et al., 2022). Furthermore, the potential for growth in developing economies is higher than in the saturated markets of developed countries, making it essential to balance profit and sustainability for long-term success (Durge & Sangle, 2020). In contrast, firms in developed countries benefit from more stable economic conditions and established institutions that support the adoption of advanced green technologies and sustainable practices (Strachan et al., 2022). Therefore, the organisational landscape of developed countries like Spain and the United Kingdom exhibits a more balanced approach to integrating GS and GC into those countries’ long-term strategies, and they are thus at an advantage in managing their economic and environmental impacts (Amores-Salvadó et al., 2015; Baranova & Paterson, 2017; Lin et al., 2019; Marín-Vinuesa et al., 2020; Scarpellini et al., 2020; Strachan et al., 2022).

To better understand GS, GC and their organisational implications, it is necessary to understand these country-specific contexts. The significant variation across countries, even among those with similar living standards (e.g., Germany and the UK or Belgium and France), requires us to heed the importance of tailoring GS and GC initiatives to regional and cultural aspects (Zhu et al., 2023). Based on our findings, we call for scholars to incorporate into their work an in-depth understanding of the geographical factors that affect the adoption of GS and GCs.

Green skills and capabilities: co-evolution and mutual reinforcementOur systematic review reveals that the existing literature does not explicitly and deeply consider the important relationship between individuals’ GS and organisations’ GC, as discussed in Section 3.3. This lack of engagement has contributed to a noteworthy imbalance in the level of engagement with GS; namely, that GC receive extensive attention in both scholarly and grey literature, while GS remain comparatively undeveloped. This imbalance may be attributable to several factors.

First, while GC are typically examined in the context of strategic management research, GS are more often central in education, HR, and psychology research, which do not always directly engage with management scholarship (e.g., Hameed et al., 2022; San Román-Niaves et al., 2025). These disciplinary silos produce a fragmented research landscape where GS and GC are rarely connected (Feeney et al., 2023). Second, as we highlight in Section 3.1, the conceptualisation of GS has become fragmented, with limited consensus on core definitions, and thus remains conceptually ambiguous, hindering the development of unified measurement tools, and contributing to their marginalisation in mainstream management research (Wegenberger & Ponocny, 2025). Third, strategic management research remains widely firm-centric, obscuring individual-level contributions and reinforcing the dominance of GC in empirical work (Felin & Foss, 2005). These dynamics collectively contribute to the underrepresentation of GS in the literature and underscore the need for more integrative, interdisciplinary approaches.