The dynamics of innovation in middle-income countries (MICs) have become increasingly complex due to globalization and the interconnected nature of economies. MICs are a significant part of the global economy; their limited infrastructure and economic stability pose particular challenges in promoting innovation (Vivarelli, 2014), which is vital for their growth and global economic health. Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between innovation and economic progress (My et al., 2024; Haldar et al., 2023), finding that innovation is a significant variable for economic growth; however, few studies have examined methods for effectively extending innovation. Innovation is a pervasive force in the global economy, shaped by factors such as income level, investment capacity, and institutional capability; thus, its intensity and scope vary significantly across nations.

Past studies have explored innovation from different dimensions. For example, Labrianidis and Sykas (2024) demonstrated that skilled migration fosters innovation when emigrants return to their countries of origin; thus, such migration may not result in brain drain. Similarly, Alhassan et al. (2021) discovered a strong connection between remittances and innovative growth, while Villanthenkodath and Mahalik (2022) supported the development of eco-friendly innovation and criticized an over-reliance on inward remittances. The existing body of economic literature emphasizes the intricate and multi-dimensional nature characterizing the nexus between remittances and innovation.

Previous studies have explored various aspects of innovation, including information and communication technology (ICT), urbanization, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, research and development (R&D), productivity, and economic growth. For example, Lopez and Martinez (2017) explored R&D and non-R&D innovation. The innovation aspect of non-R&D work encompasses acquiring new technology, purchasing sophisticated computer products (including software and hardware), obtaining licenses and patents, training associated with the introduction of new products or processes, as well as conducting feasibility studies, market research, and other methods such as production engineering and design. Odei et al. (2021) found that R&D is a key driver of regional innovation and growth, enhancing knowledge absorption for product development in both radical and incremental innovation; however, they found limited significance in R&D cooperation for both types of innovators. From this perspective, the existing literature has overlooked the contribution of remittances to innovation.

Previous research has explored remittances in association with financial development (Mallela et al., 2023; Ofori et al., 2023), economic growth (Batu, 2017), climate change (Randazzo et al., 2023), land system change outcomes (Mack et al., 2023), deforestation (Afawubo & Noglo, 2019), endogenous labor migration (Lim et al., 2023), structural transformation and urbanization (Abbas et al., 2023), and income inequality (Mallela et al., 2023), as well as FinTech development, savings, and borrowing (Lyons et al., 2022). However, few studies have partially linked remittances to innovation, with little exploration into their impact. For example, Fackler et al. (2020) found that emigration has a positive influence on innovation in countries of origin, without leading to disparities in innovation levels. Moreover, the role of remittances in economic growth has garnered significant attention in recent years, particularly for their potential to foster innovation in MICs (Islam et al., 2024). Despite this, the economic literature has largely overlooked the possibility that remittances can enhance sustainable economic growth through innovation; this study aims to fill this gap.

Existing studies have examined various economic variables that influence innovation, integrating control variables such as per capita gross domestic product (GDP), financial development, industrialization, CO2 emissions, and capital stock. These variables are essential for an inclusive analysis, as they provide a more comprehensive understanding of the channels through which remittances might affect innovation. For example, GDP per capita reflects a country’s overall economic health, which can affect its innovation capacity (Chaparro et al., 2024). Financial development can facilitate access to funding for innovative activities (Çeştepe et al., 2024), while CO2 emissions could signal environmental challenges that spur or hinder innovation (Li et al., 2024). Similarly, industrialization drives economic transformation (Forero & Tena, 2024), while capital stock—representing the physical assets available for production—is also critical in shaping the innovation landscape. Despite the significance of these variables, the literature fails to fully address their combined effect on the remittance–innovation nexus in MICs. This study aims to fill that gap, providing insights into how these variables interact with remittance inflows to influence innovation.

We selected MICs for several reasons. First, they struggle to transition from natural resource-based growth to innovation-driven progress, with few exceptions, such as the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) nations (Schot & Steinmueller, 2018). Second, MICs account for 75 % of the world’s population but contribute only 33 % of the world’s economic output (World Bank, 2024); therefore, utilizing this enormous population for innovation-related activities could help strengthen the economies of MICs. Third, only 25 of the 110 MICs have balanced data on R&D, patents, and trademarks, while 75 face imbalanced or missing data (World Bank, 2024). The selected countries exhibit a significant gap in their innovation activities; therefore, our findings could help nations seeking to enhance their innovation capacity. Conversely, the asymmetric effects of remittances on innovation in MICs have received less attention than their influence on GDP development; therefore, this study makes a significant contribution to the existing literature by presenting several novel findings. First, this study examines the asymmetric effects of remittances on innovation, providing new insights. Second, this research reveals a strong connection between positive and negative remittance shocks and innovation, providing crucial contextual insights for MICs. Third, this research is perhaps the first preliminary investigation to apply “principal component analysis” (PCA) in creating an innovation index consisting of three key proxies (patents, trademarks, and R&D). Fourth, this study’s results provide crucial insights for decision-makers in MICs seeking to develop effective policies for managing remittance inflows. These policies can promote innovation and foster economic growth, contributing significantly to the development of MICs. Moreover, future research on remittances and innovation in other contexts can build upon this study’s findings, utilizing alternative methodologies.

The rest of the manuscript is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature, Section 3 outlines the research methodology, and Section 4 presents the findings along with analysis. Finally, Section 5 concludes with a summary of the findings, implications, and an acknowledgment of this study’s limitations.

Literature reviewTheoretical underpinningRemittances are a significant source of external finance in MICs and have a dynamic role in stimulating economic activities, including innovation. The positive impact of remittances on innovation can be understood through the endogenous growth theory, which emphasizes the importance of human capital accumulation, R&D, and technological advancements in driving long-term GDP growth (Romer, 1990). Remittance inflows alleviate liquidity constraints, enabling households and firms to invest in education, skills development, and innovation-related activities. These investments are vital for developing and spreading new technologies, thereby strengthening innovation capacity (Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, 2009).

Furthermore, the knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship (KSTE) (Audretsch & Fiedler, 2024) posits that financial resources from remittances can stimulate entrepreneurial activities, thereby contributing to innovation. Remittances also facilitate knowledge transfer, supporting the diaspora knowledge network (DKN) theory (Meyer & Wattiaux, 2006), which conjectures that skilled migrants play a key role in knowledge diffusion and innovation in their home countries. DKN emphasizes the role of migrant communities in shifting financial resources, knowledge, skills, and entrepreneurial mindsets, fostering innovation. In contrast, the social capital theory (Putnam, 2000) emphasizes how remittance flows can foster trust, collaboration, and institutional support, thereby enhancing innovation in MICs and encouraging risk-taking behavior and the adoption of technology.

Positive remittance inflows can promote innovation; however, negative remittance shocks can have a detrimental effect, particularly in MICs where access to formal financial institutions is often limited. The credit market imperfection theory suggests that reduced remittance inflows can exacerbate credit constraints, limiting the ability of households and firms to finance innovation-related activities (Stiglitz & Weiss, 1981). The liquidity constraint theory further supports this, signifying that negative financial shocks can reduce R&D investment, hindering technological progress and innovation (Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, Laeven, & Maksimovic, 2006).

Empirical literatureKey economic indicators and innovationExisting research indicates a strong correlation between GDP per capita and innovation, with developed nations typically exhibiting robust innovation due to substantial investments in R&D, education, and technology (Coccia, 2020). Higher income enables more risk-taking and technological advancement, thereby increasing innovation (Broughel & Thierer, 2019); however, this relationship is not strictly linear—beyond a certain point, the influence of GDP per capita on innovation may diminish, as it is affected by factors such as institutional quality and human capital (Izadkhasti, 2023). Thus, while GDP per capita is vital, its effect on innovation depends on broader socioeconomic contexts.

Prior studies have emphasized the pivotal role of financial development in fostering innovation across economies (Zhu et al., 2020). Moreover, efficient monetary policies facilitate access to capital, allowing firms to invest in R&D activities that drive technological advancements and generate innovative outputs (Beck, Chen, Lin & Song, 2016). Furthermore, empirical studies have confirmed that countries with advanced financial sectors exhibit high rates of patent filings and technological innovation, primarily due to improved resource allocation and risk management (Zhao et al., 2021). Conversely, research has also shown that excessive financialization may lead to resource misallocation and speculative activities that impede innovative efforts (Storm, 2018); therefore, a balanced and well-regulated financial system is crucial for innovation-led economic growth.

The connection between CO2 emissions and innovation has increasingly garnered academic attention. For example, research has shown that higher CO2 emissions can drive innovation, particularly in developing green technologies, as countries and firms seek to mitigate environmental effects and comply with stricter regulations (Jiang, Pradhan, Dong, Yu, & Liang, 2024). The Porter hypothesis suggests that stringent ecological guidelines can enhance innovation, competitiveness, and economic performance (Han et al., 2024); however, the impact of CO2 emissions on innovation varies across different contexts and industries. Some studies found that excessive emissions may hinder innovation by diverting resources toward regulatory compliance rather than R&D (Zhao et al., 2024). Consequently, the relationship between CO2 emissions and innovation remains complex and context-dependent, underscoring the need for targeted policies to balance environmental goals and innovation incentives.

The relationship between industrialization and innovation is well-established, with industrialization often serving as a key driver of technological advancements and economic growth. Industrialization promotes innovation by creating demand for new technologies, enhancing infrastructure, and facilitating the diffusion of knowledge and skills across various sectors (Nayyar, 2021). As industries evolve, firms must innovate to remain competitive and advance production processes, product development, and organizational practices (Acemoglu et al., 2018). However, the impact of industrialization on innovation is not uniformly positive; in some contexts, rapid industrialization can lead to environmental degradation and resource depletion, ultimately hindering innovation efforts (Pan et al., 2022). Overall, industrialization is crucial in shaping the innovation landscape; however, its effects are moderated by several variables, including regulatory frameworks, economic growth, and access to capital and technology.

Capital stock fosters innovation by providing essential physical and financial resources to support R&D activities. With a robust capital stock, firms can invest in new technologies, machinery, and infrastructure, thereby enhancing productivity and driving innovation (Grossman & Helpman, 1991). Accumulating capital stock facilitates the approval and diffusion of innovations across industries, contributing to long-term economic growth (Howitt & Aghion, 1998). Moreover, capital stock is closely linked to a firm’s capacity to absorb and implement advanced technologies, thereby further stimulating innovation (Kim & Lee, 2020); however, the relationship between capital stock and innovation is complex. Variables such as the quality of institutional frameworks, human capital, and the overall economic environment can influence the effectiveness of capital investment in promoting innovation (Cohen & Levinthal, 1989).

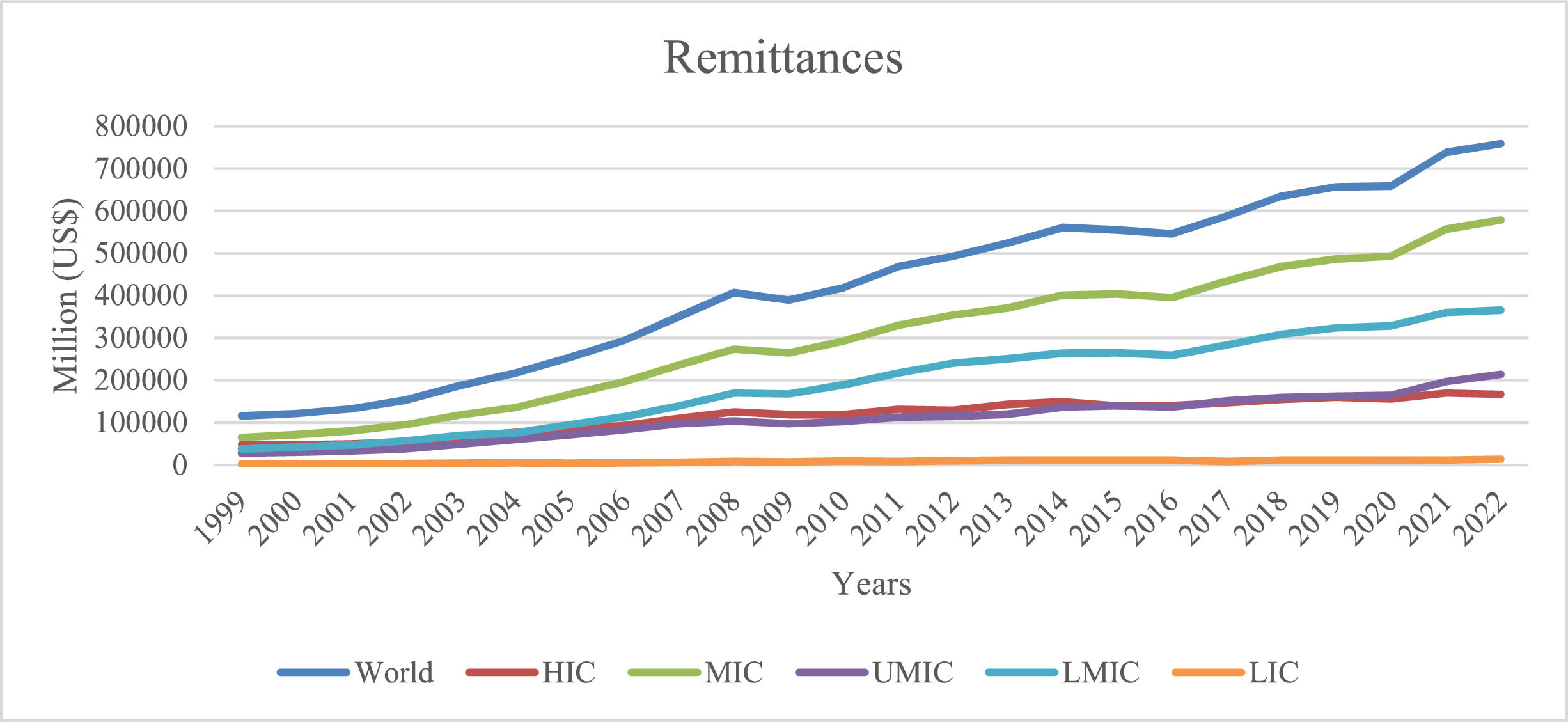

Remittances and innovation nexus in MICsRemittances are payments migrants send to their home-based nations, representing a significant revenue source for many MICs. Remittances support entrepreneurship, basic needs, healthcare, and education (Yoshino, 2020), providing a steady flow of external funds that eases credit constraints and enables increased investment in entrepreneurial activities, education, and technology—key drivers of innovation. Fig. 1 shows the trend of remittances from 1996 to 2022for different income levels. Nations are categorized according to the World Bank (2024) as follows: high-income countries (HIC), upper-middle-income countries, MIC, and low-income countries (LIC). Overall, remittances have gradually increased over the years, with the global trend outpacing the growth in remittances for individual income groups. The World Bank’s data show that MICs are leading contributors to global remittances, with an upward trend indicating sustained growth.

In contrast, innovation is vital for productivity, competitiveness, and long-term economic growth. Remarkable innovation has significantly accelerated economic development in MICs in recent years (Kaplinsky & Kraemer, 2022); the growth of significant patents, trademarks, and R&D expenditures in MICs enhances their ability to innovate (Sesay et al., 2018). Previous studies have employed a variety of proxies, including patents, trademarks, and R&D expenditures, to capture the multifaceted nature of innovation. Instead of traditional approaches, this study introduces a novel composite innovation index using PCA, which provides a more comprehensive representation of innovation for MICs. Figs. 2–4 show that MICs have experienced a steady rise in patents, trademarks, and R&D expenditures. The data reveal significant growth in innovation over the past 26 years, indicating a growing emphasis on technological advancement and economic development in these nations.

Figs. 2–4 clearly illustrate a strong upward trend in remittances and innovation proxies, signifying their potential long-term affiliation. Understanding this nexus is crucial for designing policies that leverage remittances to stimulate innovation and sustain economic progress.

Literature matrixThe literature on the affiliation between remittances and innovation is relatively sparse. A few studies have partially examined this connection; however, a comprehensive understanding remains limited. Therefore, the following review synthesizes the key constructs of foundational theories, highlighting methodological gaps and conflicting findings (Table 1).

Literature matrix on remittances and innovation.

| Author(s) | Country/Region | Key Constructs | Methodology | Main Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Becker, (1962) | Theoretical | Human capital, education, training, income | Theoretical economic modeling | Human capital increases productivity and drives long-term growth |

| 2 | Rogers, (1962) | Theoretical | Innovation diffusion, communication channels, and social systems | Conceptual framework based on empirical studies | Innovation spreads over time through communication within a social system. |

| 3 | Romer (1990) | Theoretical | Human capital, innovation, growth | Endogenous growth theory | R&D and knowledge accumulation drive long-run growth. |

| 4 | Paulson and Townsend (2004) | Thailand(2,880 Thai households (1997–1998) | Entrepreneurship, financial constraints, and credit access, | Probit and Tobit regressions | Financial constraints significantly limit entrepreneurial entry. |

| 5 | Audretsch and Keilbach (2004) | Germany (regional-level analysis) | Entrepreneurship capital, innovation, and regional economic growth | Knowledge spillovers theory | Entrepreneurship capital significantly contributes to regional economic growth. |

| 6 | Meyer and Wattiaux (2006) | Africa/Latin America | Diaspora knowledge networks (DKN) | Qualitative | Diaspora remittances and knowledge networks support innovation ecosystems. |

| 7 | Giuliano and Ruiz-Arranz (2009) | Cross-country | Remittances and financial development | Panel regression | Remittances reduce credit constraints and promote investment. |

| 8 | Beck et al. (2016) | 32 countries | Financial innovation and economic growth | Fixed effect, instrumental variable (IV) | Financial innovation increases GDP. |

| 9 | Fackler et al. (2020) | 32 European countries | Emigration, innovation, and knowledge remittances | Ordinary least squares (OLS) and 2-stage least squares (2SLS) | Emigration increases innovation via knowledge transfer. |

| 10 | Das et al. (2020) | USA | Skill immigration, innovation, wage gap | Vector autoregressive (VAR) model | Skilled immigration boosted innovation and reduced wage gaps. |

| 11 | Alhassan et al. (2021) | Sub-Saharan Africa. | Mobile money, Remittances, Financial development, and Innovative growth | Partial least squares (PLS) | There is a positive connection between the use of mobile money, remittance, financial advancement, and innovative growth. |

| 12 | Villanthenkodath and Mahalik (2022) | India (1980–2018) | Remittances, economic growth, carbon emissions, and technological innovation | Autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model | CO2, remittances, and economic growth have contributed to technological innovation |

| 13 | Haldar et al. (2023) | 16 emerging countries (2000–2018) | ICT, innovation, electricity use, renewables, economic growth | IV-generalized method of moments (IV-GMM), fixed-effects, and quantile regression | Innovation hurts growth (except for high-income) |

| 14 | Ofori et al. (2023) | 42 African nations | Financial development, Remittances, Inclusive growth | Generalized method of moments (GMM) | Remittances do not significantly drive inclusive growth, which needs a minimum of 14.5 % financial development in Africa. |

| 15 | Abbas et al. (2023) | 95 developing nations (1980–2018) | Structural transformation, urbanization, remittances, and GDP growth | VAR model | Urbanization raises living costs and attracts remittance-driven investment, reinforcing urban growth. |

| 16 | Mallela et al. (2023) | 70 developing economies (1984–2019) | Remittances, financial development, and income inequality | Panel quantile regression model | Remittances offset financial deficits in unequal countries but exacerbate them in equal ones, thereby contributing to the perpetuation of inequalities. |

| 17 | Randazzo et al. (2023) | Mexico (2008–2018) | Remittances and climate adaptation | IV model | Remittances have a positive influence on climate adaptation |

| 18 | Mensah and Abdul (2023) | Sub-Saharan Africa | Remittances and environment | Nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) | Positive remittance shocks have greater long-run effects |

| 19 | My and Tran (2024) | 71 countries (1996–2020) | Innovation and economic growth | Simultaneous equations model and 3-stage least squares (3SLS) | The positive relationship between innovation and growth |

| 20 | Zhang and Zhao (2024) | BRIC nations (1990–2020) | Natural resources, remittances, policy uncertainty, and sustainable development | Liquidity constraints | Remittances reduce R&D barriers |

| 21 | Çeştepe et al. (2024) | 21 OECD countries(1990–2018) | Technological innovation, financial development | Driscoll–Kraay and feasible generalized least squares methods | Technological innovation positively influences financial development. |

| 22 | Zhao et al. (2024) | 108 cities of the Yangtze River Economic Belt (2006–2020) | Green technological innovation and carbon reduction efficiency | Fixed-effects, moderation effects, and threshold effects models | Green technological innovation has a significant impact on pollution reduction and carbon efficiency |

| 23 | Ordeñana et al. (2024) | 61 countries (2001–2014) | High growth, innovative entrepreneurship, and economic growth | Bayesian model averaging | Innovative entrepreneurship has a positive relationship with economic growth. |

| 24 | Bergougui (2024) | Algeria (1990–2021) | Technological innovation, fossil fuel energy, renewable energy, and carbon emissions | NARDL, quantile autoregressive distributed lag, and quantile Granger causality approaches | Positive shocks in technological innovation lead to decreased CO2 emissions, whereas negative shocks increase CO2 emissions. |

| 25 | Chaparro‑Banegas et al. (2024) | 122 countries (2015–2020) | Innovation facilitators, sustainable development | Multiple linear regression | Innovation facilitators have explanatory power on sustainable development |

| 26 | Li (2024) | 151 Chinese cities across 30 provinces (2007–2020) | Financial development and innovation efficiency | OLS model and random effects model | Financial scale and efficiency have significant contributions to innovation efficiency. |

| 27 | Islam et al. (2024) | 25 Middle-income countries (1996–2021 | R&D expenditure, remittances, and economic growth | ARDL and generalized least squares (GLS) | R&D expenditure and remittances have positive effects on economic growth |

| 28 | Özyakışır et al. (2024) | Turkey (1974–2019) | Remittances, economic growth, inflation, and financial development | NARDL model | Remittances and economic growth increase financial development, whereas inflation has the opposite effect. |

| 29 | Yang et al. (2024) | China (2010–2020) | Digitalization, industrial pollution emissions, environmental investment, and green innovation | Dynamic panel model | Digitalization can reduce industrial pollution emissions, which can be further enhanced by environmental investment and green innovation. |

| 30 | Audretsch and Fiedler (2024) | Theoretical/Conceptual | Knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship (KSTE), circular economy, and entrepreneurial ecosystems | Theoretical integration | The study extends KSTE to circular economies, emphasizing the alignment of knowledge and value in promoting sustainable entrepreneurship. |

| 31 | Labrianidis and Sykas (2024) | Greek | Returning identical experts and innovation outcomes | IV method | A limited effect on scientific citations and patent filings. |

Studies directly connecting remittances to innovation are comparatively rare, indicating a noteworthy gap in understanding this association. The existing literature has investigated the nexus between remittances, financial development, and innovation, primarily in developing countries and MICs. Several studies have highlighted the positive impact of remittances on alleviating credit constraints and fostering investment (Meyer & Wattiaux, 2006; Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, 2009). Additional research supports this view by examining the role of remittance flows in financial development and innovative growth, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (Alhassan et al., 2021; Ofori et al., 2023).

Table 1 shows that previous studies have employed various econometric techniques. Methodologically, numerous studies employ diverse panel regression models (Beck et al., 2016; Haldar et al., 2023; Zhang & Zhao, 2024) or GMM estimations (Ofori et al., 2023) to measure the impact of macroeconomic factors on innovation or growth. Others apply more dynamic methods, such as vector autoregressive (VAR) models (Das et al., 2020; Abbas et al., 2023), nonlinear ARDL (NARDL) (Bergougui, 2024; Mensah & Abdul, 2023), or quantile regression (Mallela et al., 2023) to explore distributional impacts; however, these studies often overlook asymmetric impacts and nonlinearities. For example, Villanthenkodath and Mahalik (2022) established a connection between remittances and technological innovation using the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) method; however, their analysis did not differentiate between positive and negative shocks. Correspondingly, conflicting evidence appears on remittance–innovation channels—some research highlights DKNs (Fackler et al., 2020), while others point to financial development thresholds (Alhassan et al., 2021). Therefore, the NARDL method is rarely applied to remittance–innovation relationships, which are primarily suitable for capturing asymmetric effects.

The extant literature has reached a consensus regarding the positive connection between innovation and economic growth (My & Tran, 2024; Ordeñana et al., 2024); however, evidence on the direct impacts of remittances on innovation is varied. For example, Fackler et al. (2020) reported a positive knowledge transfer from emigration to innovation; conversely, Labrianidis and Sykas (2024) found partial innovation results from returning experts. Moreover, Mallela et al. (2023) found that remittances substitute for financial development in HICs but complement it in LICs, suggesting that institutional and socioeconomic heterogeneity may limit the impact of remittances.

Past empirical studies, hypotheses, and observed data trends regarding remittances and innovation in MICs show that the relationship between remittances and innovation remains ambiguous and warrants further investigation. Previous studies have primarily focused on the broader effect of remittances on economic progress; in contrast, we aim to explore their specific role in fostering or hindering innovation. Precisely investigating the remittance–innovation nexus in MICs enables this study to uncover the asymmetric impacts of remittances on innovation dynamics, offering fresh insights beyond conventional growth-focused analyses.

Despite the growing attention to these dynamics, a methodological gap remains in understanding the nonlinear and asymmetric impacts of remittance shocks on innovation, particularly in MICs. The limited use of asymmetric approaches (such as NARDL) in this domain necessitates a greater consideration of how positive and negative remittance fluctuations differentially affect innovation outcomes. Based on these insights, we present the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 Positive remittance shocks significantly and positively affect innovation in MICs.

Hypothesis 2 Negative remittance shocks significantly and negatively affect innovation in MICs.

This study uses panel data on 25 MICs1 from 1996 to 2022. Relevant data for specific independent variables in other MICs are unavailable from existing sources; therefore, this study employs a convenience sample method for selecting MICs. Previous studies have used various innovation proxies, such as R&D expenditures (Minovic & Jednak, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2020), patents (Ordeñana et al., 2024; Bucci et al., 2021; Burhan et al., 2017; Feki & Mnif, 2016; Hashmi & Alam, 2019; Saleem et al., 2019; Ulku, 2004), trademarks (Acheampong et al., 2022), scientific and technical publications, high-technology exports, and R&D as a percentage of GDP (seeAppendix A, Table A1). These indicators have been utilized individually or in combination as proxies for innovation. Some researchers used the innovation index (Mughal et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2021; Pradhan et al., 2020); however, the data for selected variables from MICs reveal significant multicollinearity among various innovation proxies. While previous research often employed multiple innovation indicators individually, we introduce a novel approach by constructing a composite innovation index using PCA that includes the most commonly used proxies: R&D expenditure (RD), patent records (PAT), and trademark records (TM). Before conducting the PCA, we assess the appropriateness of the data using Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure. Bartlett’s test exhibits that the variables are appropriately correlated for dimensionality reduction (χ²(3) = 1,389.08, p < 0.001). The KMO measure is 0.74, exceeding the suggested threshold of 0.60 (Kaiser, 1974), with individual KMOs ranging from 0.67 to 0.83. Therefore, the generated innovation index was used as the dependent variable for this study.

Remittances are a significant source of income for many MICs, and they can have a positive impact on poverty reduction, economic growth, and human development (Islam et al., 2024). Remittances can foster innovation by providing financial resources to entrepreneurs and businesses, creating a more educated and skilled workforce, and contributing to the development of a more entrepreneurial environment. The extant literature presents remittances in various dimensions. For instance, Adebayo et al. (2023) found that remittances are associated with reduced CO2 emissions. Chishti (2023) found that remittances have a positive impact on the ecological footprint, while Zhang and Ullah (2023) discovered that remittances contribute to increased green growth. Conversely, Fackler et al. (2020) stated that emigration has a positive impact on innovation in source countries. Finally, Das et al. (2020) found that skilled immigration promotes innovation and reduces wage gaps in the United States (US). Therefore, remittances are a crucial variable that influences innovation and contributes to economic growth.

Our model incorporates multiple control variables to enhance research reliability and mitigate bias by establishing a causal relationship between variables. Control variables include GDP per capita (PCI), financial development (FD), carbon dioxide emissions (CO2), industrial output (IND), and capital stock (KS). These factors are widely recognized as direct determinants of innovation within countries. All data are obtained from public and open data sources, and the data series is transformed into common logarithm values to minimize the effect of outliers. Table 2 presents the data descriptions, along with their sources.

Description of data.

| Vars | Description | Obs | Mean | Max | Min | SD | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INNO | R&D expenditure (RD), patent records (PAT), and trademark records (TM) determine the innovation index. | 675 | 0.00 | 5.57 | -3.09 | 1.64 | RD from UNESCO; PAT from WDI & TM from UNESCO (2024) & WIPO (2024) |

| KS | Capital stock in USD, current purchasing power parity (PPP) | 675 | 11.95 | 14.12 | 9.22 | 0.91 | PWT 10.01 GGDC (2024) |

| FD | Financial development (FD) (composite) index by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) | 675 | −0.54 | −0.13 | −1.27 | 0.25 | IMF (2024) |

| FR | Foreign remittances in USD current PPP | 675 | 9.17 | 11.13 | 6.04 | 0.80 | WDI (2024) World Bank (2024) |

| PCI | Per capita GDP values in current USD, converted by PPP | 675 | 3.98 | 4.57 | 2.92 | 0.30 | |

| IND | Industry ( % of GDP) (including construction) | 675 | 1.47 | 1.70 | 1.21 | 0.09 | |

| CO2 | CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita) | 675 | 0.48 | 1.19 | −0.49 | 0.36 |

Note: All variables are reported as common logarithms.

All variables are selected based on established literature and existing references to achieve the research objectives; however, innovation is defined as a function of remittances and a set of control variables. Accordingly, our foundational regression model is structured as follows:

Here, “INNO” means innovation, “FR” represents foreign inward remittances, and “Z” represents a group of control variables. The static baseline regression models below examine the influence of remittances on innovation in MICs. We transform it into a linear Eq. (2) by applying the logarithm to both sides of Eq. (1) and incorporating relevant control variables. The baseline innovation equation is represented in the coefficient notation.

Here, εit denotes the residual term, i means cross-section, and t stands for time. β1 represents demonstrations of the coefficients of the predictors, and α0 represents the intercept. LINNOit is the endogenous variable, while LFRit is the exogenous variable. γ′ is the coefficient for control variables (CV), while Zit is the vector of CV, including LPCIit, LFDit, LCO2it, LINDit, and LKSit.

We assess cross-sectional dependence (CD) using the Pesaran (2004) CD test. Given the limitations of traditional unit root tests, we employ second-generation tests, including the cross-sectionally augmented Im, Pesaran, and Shin (CIPS) test and the cross-sectional augmented Dickey–Fuller (CADF) test. After confirming the existence of long-run equilibrium associations among the variables, we conduct a more in-depth analysis of cointegration using Westerlund’s (2007) panel cointegration tests. These tests allow for heterogeneity in the slope coefficients across individual units and CD among the panel variables.

We employ the panel NARDL model introduced by Shin et al. (2014) to investigate nonlinear associations and asymmetries in both the short and long run. We first verify that the panel data meet the necessary criteria. The panel NARDL model effectively handles mixed orders of integration (I[0] and I[1]), making it suitable for analyzing nonlinear relationships and long-term dynamics. The panel NARDL model addresses cross-sectional dependence, serial correlation, and endogeneity; however, the panel NARDL model can be constructed by incorporating both positive and negative changes in independent variables (LFR). Eq. (3) presents a simplified long-run NARDL equation:

Here, αi means country-specific intercept, and β1+LFR_POSit denotes long-term coefficients of remittances for positive change. β1−LFR_NEGit represents long-term coefficients of remittances for negative change. Eq. 4 allows us to obtain the short-term dynamics of the affiliation.

In this framework, δi denotes country-specific intercept for the short run, and ⋌jpresents short-run coefficients for lags of the predicted variable; φj represents control variables. ωj+and ωj− denote the short-term coefficients associated with lags of positive and negative remittance changes, respectively. The error correction term is denoted by θECTit−1, which measures the rate of convergence to the long-run equilibrium.

We use the Dumitrescu–Hurlin (D–H) (2012) panel causality check to identify the pattern of causation among variables. All coefficients are expected to exhibit cross-sectional variation. Eq. 5 provides a concise overview of the D–H model.

In this equation, βi means constant, δi represents the coefficient slope, and αi denotes the lag parameter. Eq. 6 outlines the null and alternative hypotheses, providing a precise framework for statistical analysis.

Despite the lack of homogeneous Granger causality in all cross-sections, the alternative hypothesis posits that a panel data approach could reveal at least one causal relationship between the variables.

Results and discussionCross-sectional dependency (CD) test and unit root test (URT)The preliminary analysis employs cross-sectional dependency (CD) tests due to the commonality of data across different countries. Table 3 presents (column 2) the empirical CD findings utilizing the Pesaran CD test (2004), showing that the null hypothesis is rejected at a 1 % significance level in the series. The findings reveal CD in designated variables, driven by interconnected factors such as macroeconomic conditions, globalization, and national economic aspirations.

CD, URT, and variance inflation factor (VIF) outcomes.

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.0.1

We then employ second-generation unit root tests (CIPS and CADF) due to the presence of CD, finding that the cross-sections are generally stationary, with varying orders of integration. Table 3 presents the URT results, indicating that the variables are either I(0) or I(1). We also conduct unit root tests (URTs) for I(2) integration, determining that none of the variables exhibit I(2) integration; therefore, the NARDL approach is appropriate for our study.

Table 3 also displays the results of the multicollinearity variance inflation factor (VIF) test (column 7). The average VIF values are 1.96, with all individual values below 2.32; therefore, the VIF test results indicate that there is no multicollinearity issue in the model.

Panel cointegration testAfter confirming long-term equilibrium associations among variables through URTs, we conduct a more in-depth analysis of cointegration using Westerlund’s error-correction-based (ECM) panel cointegration tests.

The study utilizes Gt and Ga as group-mean statistics as well as Pt and Pa as panel-mean statistics. This approach allows us to test for cointegration at the individual country level and across the panel as a whole, with the null hypothesis rejected. Table 4 shows Westerlund’s (2007) ECM panel cointegration test results, indicating significant cointegration among the variables and rejecting the null hypothesis of no cointegration across all tests. Gt and Pt utilize conventional standard errors, while Ga and Pa adjust for heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation. The test outcomes reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration at the 1 % significance level based on robust bootstrap p-values; therefore, the panel reveals cointegration, indicating that the selected variables are long-term connected.

Regression resultsThe pooled mean group model employs a nonlinear ARDL approach, specified as NARDL (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1). The maximum lag for the dependent variable is set to 1 for automatic selection. Dynamic regressors are also automatically selected based on the Akaike information criterion. Table 5 presents the long-term and short-term NARDL outcomes. Revealing that all independent variables, except for negative remittances (LFR_NEG) and industrialization (LNIND), positively affect innovation, with LNIND being statistically significant at the 1 % level in the long term.

The long- and short-term outcomes of panel NARDL.

Note: *** = p < 0.01 and ** = p < 0.05.

The positive and statistically significant coefficient of LNFR_POS indicates that positive remittance shocks are positively associated with innovation, signifying a long-run stimulative effect on innovation. Conversely, the negative and highly significant coefficient of LNFR_NEG indicates that adverse remittance shocks have a detrimental effect on innovation. Moreover, the magnitude exceeds the positive effects, suggesting a strong asymmetry in the long-term impact of remittances on innovation. Therefore, the findings reveal an apparent asymmetry in the effect of remittances on innovation: positive remittance shocks significantly boost innovation, while negative shocks exert a far more significant adverse impact. Consequently, remittances play a dual role in MICs, fostering innovation during positive inflows while posing considerable risk when flows decrease. The outcome is similar to that of Fackler et al. (2020), who found that emigration influences innovation in source nations despite not spreading asymmetries. Correspondingly, Das et al. (2020) proposed a policy-guided hypothesis that skilled immigration encourages innovation and reduces wage gaps in the US. Thus, remittances tend to correlate with higher innovation; countries with higher remittance inflows tend to accelerate innovation activities due to their governments’ greater capacity for investment.

In contrast, LPCI’s 1 % level positive coefficient indicates that higher per capita GDP significantly enhances innovation, underscoring the crucial role of economic development in fostering innovation in the long term. This result aligns with Galindo and Méndez (2014). Subsequently, we found that financial development (LFD) has a significant influence on innovation, demonstrating that improved financial systems can enhance innovation activities in MICs over the long term. Our empirical findings on FD outcomes align with key macroeconomic theories and literature, partially supporting the work of Li (2024) and Hsu et al. (2014).

The significant 1 % level coefficient of LCO2 (CO2 emissions) indicates that higher CO2 emissions are positively associated with innovation, suggesting that environmental challenges drive the development of long-term, sustainable technologies. This outcome is consistent with the results of Mehmood et al. (2024) for Pakistan and Alexiou (2025) for developed countries. The results indicate that CO₂ emissions and innovation are positively correlated; however, this may be due to the transitional phase of industrialization, when energy-intensive production initially follows technological improvements (Bekun et al., 2025). This correlation may also occur at the early stage of the environmental Kuznets curve, where the heavy use of nonrenewable energy may increase innovation but temporarily worsen the environment (Alexiou, 2025). Therefore, MICs should implement policies that promote the adoption of low-carbon technologies, energy-efficient production processes, the integration of renewable energy sources, and green R&D incentives. Such policies can foster innovation and mitigate emissions, thereby supporting environmental sustainability goals. Conversely, Bergougui (2024) discovered that negative technological innovation shocks can increase CO2 emissions, while positive shocks have the opposite effect.

The industrialization (LIND) coefficient is consistently negative and highly significant, indicating that industrialization has a negative long-term impact on innovation. The findings align with those of Bustos et al. (2019), who found that the expansion of low-tech industries diverted workers from high-tech sectors, ultimately hindering growth in manufacturing productivity. In contrast, Zou (2024) and Yang et al. (2024) demonstrated the positive impact of industrialization on innovation. The following frameworks can theoretically contextualize the negative connection between industrialization and innovation. First, the early deindustrialization hypothesis (Rodrik, 2016) suggests that many MICs experience manufacturing decline before achieving satisfactory technological maturity, thereby creating structural gaps in their innovation capabilities. Second, the technology trap phenomenon (Mazzucato, 2013) clarifies how industrialization designs dominated by low-value-added production may force out R&D investment while constraining economies into imitative activities. Third, structural hysteresis effects (Andreoni & Chang, 2019) underscore how historical industrial policies can create path dependencies that hinder the transition to knowledge-intensive production.

Finally, the significant positive coefficient of LKS (capital stock) at the 1 % level emphasizes the crucial role of physical capital investment in driving long-term innovation. Our finding aligns with Fengju et al. (2020), who discovered a reciprocal affiliation between sustainable innovation ability and capital stock with industry-specific variations. Therefore, our findings are indispensable for enhancing innovation activities in MICs, where remittances, CO2 emissions, GDP per capita, FD, and capital stock are steadily increasing.

In contrast, the short-run dynamics are replicated in the coefficients of the differenced variables and the error correction term (COINTEQ01). The significant error correction term of –0.373 (p < 0.0001) specifies a swift adjustment of 37.3 % per period toward long-run equilibrium, indicating that short-run disruptions to innovation are rapidly corrected. The coefficients for positive and negative remittance shocks are insignificant in the short run, suggesting that remittance shocks have no immediate impact on innovation. The long-run counterparts dominate the short-run effects.

The empirical results reveal asymmetric impacts in both magnitude and temporal dimensions. The short-term remittance shocks exhibit limited innovation impacts; however, their long-term effects are substantially more substantial and statistically significant, with the system correcting disequilibria at a rate of –0.37 % quarterly. This framework suggests three essential features for innovation systems in MICs. First, the delayed positive effect indicates innovation earnings require (a) time-consuming human capital growth through remittance-funded education (Yavuz & Bahadir, 2022), (b) gradual technology approval from migration networks (Meyer & Wattiaux, 2006), and (c) institutional growth to support R&D commercialization. Second, the stronger negative long-term coefficient indicates that innovation systems change remittance dependencies. Moreover, rapid drops damage ongoing research projects and hinder the retention of skilled labor, consistent with Djeunankan et al.’s (2023) findings on threshold effects. Third, the adjustment speed confirms notable persistence in the innovation systems of MICs, reinforcing why short-term remittance volatility has muted effects, while sustained flows yield compounding knowledge spillovers (Audretsch & Fiedler, 2024). Therefore, policy implications accordingly emphasize long-term stability over short-term stimulus.

Conversely, the positive and significant short-run coefficient (0.67) for GDP per capita emphasizes its ongoing positive influence on innovation. In contrast, the short-run coefficients for FD, CO2 emissions, industrialization, and capital stock are insignificant. This outcome suggests that their effects on innovation are primarily long-run in nature.

Table 6 displays the residual diagnostic check and long-term asymmetry tests. The residual diagnostic check using the Pesaran CD test presents a CD value of –1.257 and a p-value of 0.208, indicating no discernible cross-sectional dependency. Therefore, the null hypothesis of no CD cannot be rejected, suggesting that residuals are relatively independent across different cross-sections in the panel data. In contrast, the long-term asymmetry test results in Table 6 also show strong evidence against the null hypothesis of symmetric effects (H0: C1 = C2). The statistically significant test statistics (t, F, and χ2) confirm significant differences between the coefficients C1 and C2, indicating a long-term asymmetric affiliation between remittances and innovation in MICs.

Robustness analysisTo ensure the robustness of the results regarding the effect of remittances (both positive and negative shocks) on innovation in MICs, we employ additional analyses using the dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) approach in conjunction with the NARDL method. The DOLS technique yields results consistent with the NARDL outcomes, confirming the reliability of the initial findings in Table 7. The DOLS approach accounts for endogeneity, while serial correlation confirms the robustness of the outcomes, particularly in the long-run dynamics. Therefore, the DOLS method confirms our findings using the NARDL approach, even after controlling for per capita GDP, CO2 emissions, FD, industrialization, and capital stock.

We employ the D–H causality test to determine the causal relationships between remittances and innovation, revealing bidirectional causality in 23 cases and unidirectional causality in 5 cases. Table 8 presents the outcomes of the causal relationships related to the dependent variable (innovation), which comprises five bidirectional and two unidirectional variables. The results reveal that all designated variables, except for positive remittance shocks and FD, exhibit unidirectional causation with innovation (LFR_POS→LINNO and LINNO→LFD), indicating that positive shocks and FD have a favorable impact on innovation. Conversely, negative remittance shocks, GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, industrialization, and capital stock are causally related in both directions with innovation (LFR_NEG ↔ LINNO, LPCI ↔ LINNO, LCO2 ↔ LINNO, LIND ↔ LINNO, and LKS ↔ LINNO); therefore, they have a reciprocal affiliation with innovation.

Outcomes of pairwise D–H panel causality test.

Note: *** = p < 0.01 and * = p < 0.1.

On the contrary, all other designated variables have a two-way causal affiliation, except for three variables, which denote that they have a positive effect on one another, and four variables negatively affect one another, and vice versa. The remaining three unidirectional variables are LFR_POS→LPCI, LIND→LFD, and LFR_POS→LIND, indicating that positive shocks to remittances lead to increased GDP per capita, industrialization stimulates FD, and positive shocks to remittances have a positive impact on industrialization. The panel NARDL results are confirmed as precise, and their robustness is verified by the 23 feedback and 5 unidirectional causations; therefore, the series demonstrates a causal connection between the chosen predictor and the predicted variables.

ConclusionThis study investigates the asymmetric impact of positive and negative remittance shocks on innovation in MICs between 1996 and 2022. We establish cointegration relationships among the variables using the Westerlund cointegration technique. The panel NARDL approach and D–H causality test are used to explore the interconnectedness between these variables. The NARDL framework, validated by Westerlund (2007), employs cointegration tests and bootstrap causality analysis. This approach is particularly well-suited for capturing the asymmetric and nonlinear relationships between remittances and innovation, representing a key advancement beyond conventional linear models. The cointegrated relationships (confirmed at p < 0.01) ensure that long-run parameter estimates are unbiased, while the error correction term (ECT = –0.37***) confirms the presence of Granger-causal dynamics.

Our analysis reveals significant long-term associations between innovation and the selected variables, with notable asymmetries in the impact of remittances. The positive effects of remittances on innovation are significant in the long run; however, negative shocks have a more pronounced impact. Other factors, such as FD, GDP per capita, and capital stock, drive innovation. Moreover, industrialization hinders innovation in MICs, possibly reflecting early deindustrialization and sector-specific structural challenges. CO₂ releases have a positive influence on innovation, suggesting multifaceted connections between economic growth and environmental concerns. In the short term, only GDP per capita has a substantial positive impact on innovation. The model confirms the presence of strong error correction, indicating that deviations from the long-term equilibrium are adjusted over time. Moreover, our findings are consistent with the paired D–H panel causality tests, which indicate a bidirectional causal connection between most of the variables.

Our empirical findings closely align with the previously outlined theoretical framework. The positive long-run association between remittances and innovation supports endogenous growth theory (Romer, 1990); remittances appear to narrow knowledge gaps and enhance human capital accumulation, which are key drivers of endogenous growth. The asymmetric effects (more substantial negative effects from remittance reductions) align with liquidity constraint theory (Paulson & Townsend, 2004), emphasizing how financial limitations hinder innovation when remittance flows decline. Moreover, the statistically significant gradual adjustment process (–0.37***) reflects the path-dependent nature of innovation systems theorized in knowledge spillover frameworks (Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004). Collectively, these findings illustrate the multifaceted theoretical channels through which remittances affect innovation routes in MICs.

The empirical results yield policy implications that are significant for remittance stability and promoting innovation in MICs, which are susceptible to negative shocks. Policymakers should consider the following strategies to utilize remittances for innovation-led growth. First, implementing financial stabilization mechanisms is vital to safeguard remittance inflows against volatility. To maximize innovation by mitigating volatility, MICs should adopt the following stabilization mechanisms. (1) Expand remittance sources by tracking bilateral labor agreements with various host countries. (2) Formalize remittance channels into formal financial systems (mobile banking or diaspora bonds) to reduce volatility. (3) Establish counter-cyclical buffer funds (sovereign wealth funds or remittance-backed securities) to confirm financial stability during economic recessions. (4) Provide incentives to high-skill migration with policies that inspire skilled diasporas to invest in technology transfer via tax incentives for startup investments. Second, institutional frameworks should be established to systematically channel remittances toward innovation-enhancing investments. Specifically, (1) generate dedicated R&D funding spaces for remittance-backed projects, (2) familiarize tax incentives for technology improvement in receiver organizations, and (3) develop targeted education programs to produce human capital in innovation-driven sectors. Third, due to the long-term advantages of innovation returns, policies should boost patient capital methods. The initiative involves creating financial products with extended maturity periods and establishing public–private partnerships to enhance the innovative impact of remittance flows. Fourth, the negative correlation between industrialization and innovation suggests that without proper policy, industrial growth in MICs may hinder innovation-led growth. Therefore, industrial policies should focus on sector-specific strategies to facilitate the transition from low-tech to high-tech industries, thereby creating sustainable industrialization. Finally, to address the positive correlation between CO2 discharge and innovation, innovation policies should engage in ecological deliberations, encourage the adoption of green technologies, and promote sustainable innovation pathways to balance economic growth with environmental sustainability. Targeted policies, such as (1) tax credits for clean energy patents, (2) issuing “green” diaspora bonds, and (3) offering R&D subsidies conditioned on reducing emissions, can help channel remittance-driven innovation into sustainable sectors.

Despite its results and broad policy implications, this study has its limitations. The study includes only 25 MICs due to the unavailability of data from other middle-income countries. The current research accounts for unobserved heterogeneity through panel estimation methods; however, it does not test regional (upper or lower MICs) or cultural subgroup effects. Future research could explore the geopolitical heterogeneity in remittance–innovation associations by concentrating on specific geopolitical regions (e.g., Southeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, or Latin America). Future studies could also (1) integrate Hofstede cultural indices or (2) group nations by diaspora features. Future research could similarly extend the variables to investigate the symmetrical and asymmetrical effects of institutional quality, governance structures, ICT, education levels, technology adoption, and energy sources on innovation. This study’s methodological approaches can be utilized to track firm-specific innovation products resulting from remittance-funded R&D. Future research can also explore institutional frameworks for knowledge transfer related to migration, aiming to identify policy conditions that can inspire innovation.

Funding sourcesThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Data availability statementData will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMd Zahidul Islam: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Md. Shamim Hossain: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Conceptualization. Mohammad Bin Amin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Md. Mourtuza Ahamed: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation. Judit Oláh: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This research was supported by the University of Debrecen Program for Scientific Publication.

Literature matrix on innovation in the timeline.

| Author(s) | Time | Countries | Proxy of Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ulku (2004) | 1981–1997 | 20 OECD & 10 non-OECD | Patents |

| Hasan and Tucci (2010) | 1980–2003 | 58 Countries | R&D expenditures and patents |

| Pece et al. (2015) | 2000–2013 | 3 CEE countries | Patents, trademarks, and R&D expenditures |

| Feki and Mnif (2016) | 2004–2011 | 35 developing countries | Patents |

| Pradhan et al. (2017) | 1970–2016 | 32 OECD nations | Patents and R&D expenditures |

| Burhan et al. (2017) | 2005–2010 | 43 PFROs & India | Patents |

| Sesay et al. (2018) | 2000–2013 | BRICS | Patents, trademarks, and R&D expenditures |

| Hashmi, R., & Alam, K. (2019) | 1999–2014 | 29 OECD countries | Patents |

| Saleem et al. (2019) | 1972–2016 | Time series data from Pakistan | Patents |

| Pradhan et al. (2020) | 2001–2016 | 19 Eurozone countries | R&D, patents, trademarks, scientific and technical journal publications, R&D% of GDP, and high technology exports |

| Ahmad et al. (2020) | 1984–2016 | 22 emerging nations | Patents |

| Nguyen et al. (2020) | 2000–2014 | 13 G-20 nations | R&D spending (% GDP) |

| Forson et al. (2021) | 1990–2016 | 25 sub-Saharan African countries | R&D, patents, and the number of scientific publications |

| Bucci et al. (2021) | 1983–2007 | 18 OECD | Patents |

| Gyedu et al. (2021) | 2000–2017 | G7 & BRICS | R&D, patents, and trademarks |

| Bekana, D. M. (2021) | 1996–2016 | 37 sub-Saharan African | Scientific and technical journal publications |

| Yu et al. (2021) | 2016–2019 | 37 OECD countries | Global innovation index |

| Minović, J., & Jednak, S. (2021). | 2000–2017 | 9 EU Countries | R&D expenditures |

| Mughal et al. (2022) | 1990–2019 | 5 South Asian countries | Technological innovation index |

| Acheampong et al. (2022) | 1995–2019 | 27 EU countries | Trademarks |

| Ahmad & Zheng (2023) | 1981–2019 | 36 OECD countries | Patents |

| Ordeñana et al., (2024) | 2011–2023 | 61 countries | Patents |

MICs: Middle-Income Countries; GDP: Gross Domestic Product; PCA: Principal Component Analysis; OLS: Ordinary Least Square; FMOLS: Fully Modified Ordinary Least Square; DOLS: Dynamic Ordinary Least Square; D-H: Dumitrescu-Hurlin; GMM: Generalized Method of Moments; FR: Foreign Remittances; INNO: Innovation; FDI: Foreign Direct Investment; FD: Financial Development; KS: Capital Stock; PCI: Per capita GDP; IND: Industry; OECD: Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development; CEE: Central and Eastern European Countries; HICs: High-Income Countries; UMIC: upper-middle-income countries; LIC: Low-Income Countries; WDI: World Development Indicator; IMF: International Monetary Fund.

Upper-MICs: Argentina, Kyrgyz Republic, Russian Federation, Colombia, Peru, Armenia, Paraguay, China, Costa Rica, Bulgaria, Mexico, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Thailand, Serbia, Brazil, South Africa, and Malaysia; Lower-MICs: Iran, Ukraine, Egypt, India, Tajikistan, Mongolia, Tunisia (World Bank, 2024)