Over the years, the over-extraction and unsustainable utilization of natural resources has started to pose a severe environmental risk, necessitating immediate action on issues related to climate change. Therefore, this study examines the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk, and whether financial technology (FinTech) and institutional quality moderate this relationship in the context of the top 27 contaminating countries from the years pertaining to 1995 to 2022. Using the novel Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) approach, our study analyzes heterogeneous long-run coefficients across 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th quantiles of environmental risk. In this regard, the MMQR findings have revealed that natural resources rent leads to an increase in the environmental risk, while FinTech and institutional quality tend to mitigate it. The moderation effect models revealed that both FinTech and institutional quality suppress the adverse environmental outcomes that are exerted by the natural resources rent. The Driscoll and Kray standard error (DKse) and Fully Modified Ordinary Least Square (FMOLS) estimation techniques confirm the robustness of the MMQR findings. These findings emphasize that policymakers and think tank initiatives should promote FinTech and robust institutions to encourage sustainable resource utilization in order to mitigate the environmental crisis.

The availability and access to natural resources is critical in facilitating the growth of international commerce and capital formation. The production of goods is mainly dependent on the availability of natural resources. If utilized to their potential, the abundance of natural resources has the capability to support economic growth, improve job prospects, and enhance the living standards of the public in a significant manner (Nwani, Okere, Dimnwobi, Uche & Iorember, 2025). Using natural resources tremendously impacts a country's economic, ecological, and social prosperity (Warr, Menon, & Yusuf, 2012). Despite all these benefits, there is a considerable concern among policymakers and think tanks regarding the unfavorable environmental outcomes that follow the excessive use of a country’s natural resources (Nwani & Adams, 2021; Okere, Dimnwobi & Fasanya, 2025). Natural resources and their use is one of the significant factors responsible for the increase in the concentration of Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the atmosphere (M. Yang, Magazzino, Awosusi & Abdulloev, 2024). CO2 emissions trigger a perilous environmental risk that puts multiple forms of life and the environment in danger. Thus far, these environmental risks have created and led to grave global challenges such as a diminished ozone layer, flooding, and environmental pollution. Consequently, air contamination in several cities of India and China have led to the triggering of cardiovascular illnesses, and has become unsafe for humans, year after year (Kumar, Sasidharan & Bagepally, 2023). Therefore, in order to address these alarming changes, the UN's Sustainable Development Goal 13 (SDG) requires stakeholders and government officials to develop efficient and effective strategies for the mitigation of environmental risks (Kaewsaeng-on & Mehmood, 2024).

The advancement of technology has brought about a groundbreaking revolution in the financial industry. The advent of financial technology (FinTech), which is a convergence of formal financial services and technological advancement, has profoundly influenced the financial sectors of countries by streamlining automated solutions that are user-friendly, accessible, operationally efficient, and transparent (Fang, Chung, Lu, Lee & Wang, 2021). In addition to this, FinTech also provides multifold benefits that can be instrumental in developing decarbonization strategies. For instance, FinTech eliminates the gap between lenders and borrowers by creating dynamic markets that can be effective in bridging financial service providers and clients (Tao, Umar, Naseer & Razi, 2021). Low-carbon and clean energy investments that are made through FinTech channels can speed up the process of decarbonization (Dong & Huang, 2024). In this regard, several studies have identified the favorable environmental outcomes of FinTech (H. Feng & Li, 2024; Udeagha & Muchapondwa, 2023). FinTech can also optimize the green initiatives' financial elements while reducing carbon emissions simultaneously (Bel Hadj Miled, 2025). Apart from FinTech, the credibility of institutions is among the factors that continue to gain substantial attention from the stakeholders when it comes to the development of carbon mitigation strategies (Zheng et al., 2025). The quality of the institutions can be differentiated and gauged according to their usage of different indicators such as constitutional and bureaucratic organization, governance effectiveness, environmental legislation, democratic structure, rule of law, political stability, and corruption control (Sequeira & Santos, 2018; Ul-Durar, Bakkar, Arshed, Naveed & Zhang, 2025). The politically stable countries are better positioned when it comes to the adoption of sustainable practices, which are mandatory for mitigating environmental risks (Kirikkaleli & Osmanlı, 2023). Furthermore, robust institutions through the channels of corruption control, environmental legislation, and the rule of law can enforce environmental risk mitigation initiatives (Atta, Sharifi & Ying Lee, 2024).

The usefulness of FinTech and institutional quality extends beyond environmental outcomes; these elements have considerable potential for managing natural resources that are needed to mitigate environmental risk. In a collaborative manner, FinTech and institutional quality can help lay a necessary foundation for the sustainable utilization of natural resources. Ultimately, it is the efficient utilization of natural resources that can lower CO2 emissions (Adebayo et al., 2023). In this context, Tiwari (2024) heightened the critical importance of FinTech for effectively managing natural resources, which can mitigate their adverse environmental impact. Further evidence from China elucidates the potential of FinTech for sustainable resource management (Niu, He & He, 2024). FinTech is also recognized for promoting total factor productivity (Liu, Kang & Wang, 2024), and may also augment the efficiency of the extraction and consumption of natural resources. Moreover, FinTech can help to limit CO2 emissions by increasing the productivity of resource utilization in the natural resource-based industries (Awais, Afzal, Firdousi & Hasnaoui, 2023). On the other hand, clean technologies are necessary for financial sector innovation since using unsustainable FinTech development methods might increase energy consumption and CO2 emissions (Lisha et al., 2023).

Other than FinTech, strong governing institutions are also essential for implementing critical environmental risk mitigation strategies, including sustainable utilization of natural resources. Whereas weak institutions may be unable to implement sustainable environmental policies, which are necessary for controlling environmental risks. According to Barma, Kaiser and Le (2012), natural resources rents can be effectively utilized for promoting sustainable development through the lens of strong government institutions. Robust government institutions also reflect the capacity of the government to utilize natural resources for favorable environmental outcomes (Tiba & Frikha, 2020). More precisely, Nwani and Adams (2021) and Badeeb, Lean and Shahbaz (2020) noted that natural resources extraction in countries with weak institutions and governance produces adverse environmental outcomes. Nonetheless, this evidence enlightens and educates institutions on their critical role in channeling natural resources towards achieving CO2 neutrality targets.

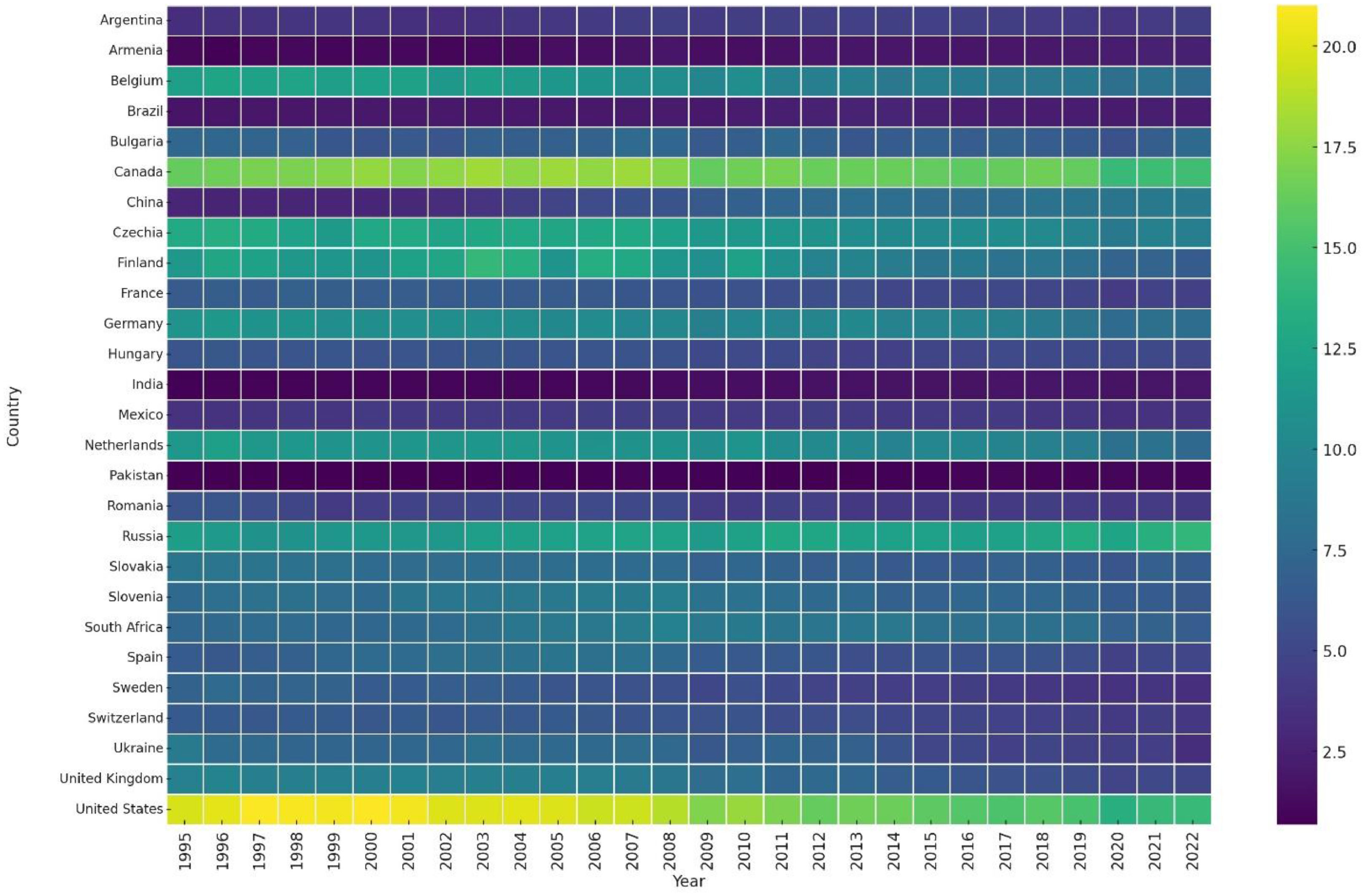

This research examines the pressing issue of environmental risk among the top 27 polluting nations, and their progressive adaptation of natural resource rents, FinTech, and institutional quality to mitigate potential environmental risks. However, this research contributes to the academic literature in the following manner: First, unlike traditional examinations in environmental outcomes such as sustainability (Okere et al., 2025), pollution (Mesagan & Vo, 2023), and quality (Bulut, Atay-Polat & Bulut, 2024), this research represents a pioneering effort to examine the impact of natural resources rent on the environmental risks. This research stipulates that CO2 emissions are among the key risks that are attributed to the environment. In this regard, the z-score for the CO2 emissions metric tons per capita has been taken into consideration to make approximations about the environmental risk. Second, several extant studies have examined the impact of FinTech on the environmental outcomes. However, limited attention has been paid to exploring its moderating role in the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk (J. Chen & Chen, 2024). Furthermore, this investigation surpasses the prior studies by utilizing a comprehensive FinTech index based on diverse indicators such as mobile phone subscription, access to the internet, and financial development. Third, the academic literature concentrates on the direct impact of institutional quality on environmental outcomes (Qayyum, Zhang, Ali & Kirikkaleli, 2024; Xaisongkham & Liu, 2024). The question of how institutional quality can influence the nexus between natural resource rent and environmental risk is a topic of substantial importance. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that this nexus has received limited attention in prior empirical studies. The current research aims to address this gap by examining the moderating role of institutional quality in the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk. Fourth, as far as we are aware, this research is one of the few that have employed the novel method of moments quantile regression (MMQR) to comprehend these linkages between various quantiles. This technique provides more reliable inferences than the traditional mean regression methodology. Fifth, the UN's Sustainable Development Goal 13 (SDG 13) has heightened the need to take urgent action against the risk of climate change. In this regard, the outcomes of this research illustrate prudential policy recommendations for the stakeholders of the top 27 polluting countries under the umbrella of SDG 13. The WorldBank (2024) has declared these countries as the top contributors to environmental risk, with a share of the USA (12.52 %), China (33.39 %), India (6.638 %), Germany (1.783 %), and Russia (5.075 %) respectively, in the world's CO2 emissions. Apart from that, Russia, India, China, Brazil, and South Africa account for 50 % of the world’s population and contribute nearly 25 % to global GDP (Udeagha & Muchapondwa, 2023; Wei, Yue & Khan, 2024). Fig. 1 displays the heatmap of CO2 emissions of these countries from 1995 to 2022.

The subsequent sections of the study are grouped as follows: The second section presents an in-depth assessment of the pertinent academic literature. The third section outlines the methods and resources employed for conducting the study. Section four presents results and discussion, while section five discusses the study's conclusions and proposed recommendations.

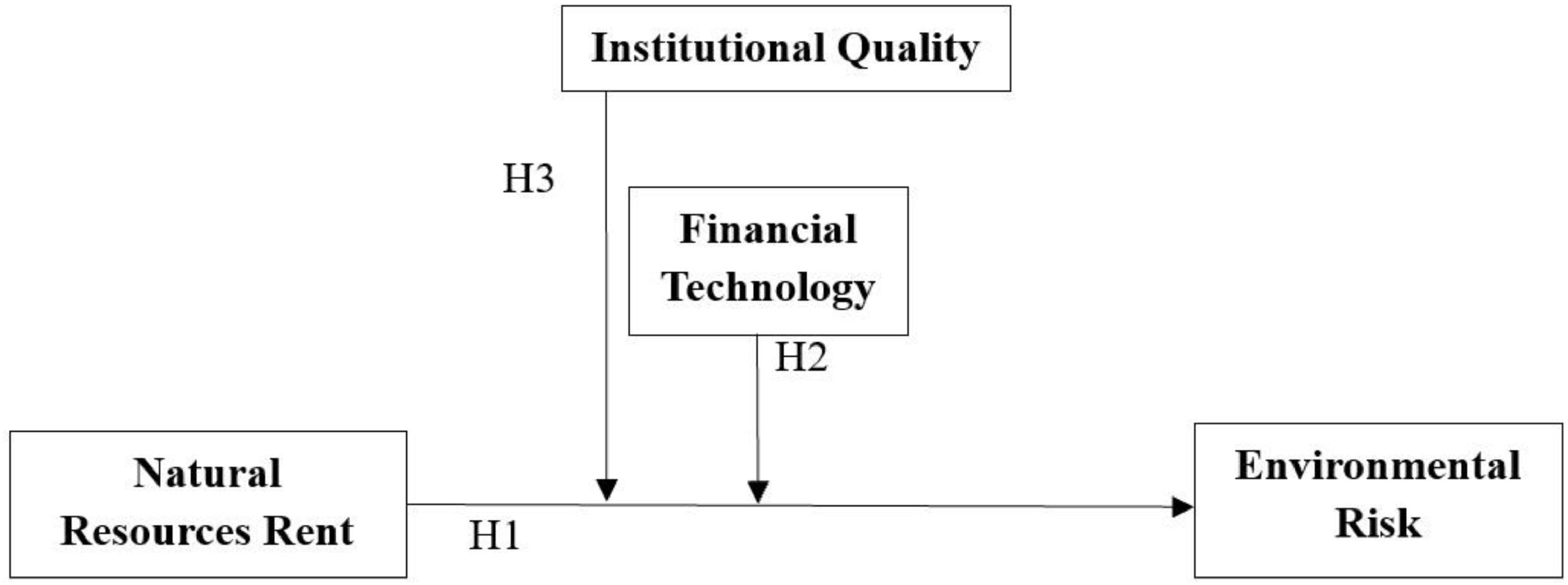

Literature reviewTheoretical underpinningThe study has incorporated the well-known Stakeholder Theory (Friedman, 1937) to develop a robust theoretical framework that can be used to examine the dynamic relationship between institutional quality, FinTech, natural resources rent, and environmental risk. The Stakeholder Theory urges that the heavy CO2-emitting business should balance ecological and economic prosperity in order to safeguard the interests of all stakeholders (Qian & Yu, 2024). Within this framework, natural resources hold a crucial place for the countries' economic, ecological, and social well-being (Sun et al., 2024). It is noteworthy that despite the favorable economic and social outcomes, the rent from natural resources is deemed to be a risk to the environment. The excessive and inefficient use of natural resources tend to trigger CO2 emissions, which in turn increases environmental risks by manyfold (Okere et al., 2025). Analyzing from the lens of stakeholder theory, FinTech and institutional quality can potentially serve and accomodate environmental stakeholders by affecting the nexus between natural resource rent and environmental risk. FinTech can enhance the efficiency of responsible investments by removing information asymmetry and improving the transparency and flow of green funds, thereby contributing to the sustainable utilization of natural resources. According to Xu, Jin and Yang (2024) FinTech is instrumental in funding green projects, which could be a viable strategy to mitigate environmental risk. Khan, Rahman, Saha, Alam and Mahmood (2024) enlighten the potential of FinTech to mitigate the adverse effects of the natural resources curse. From an empirical perspective, J. Chen and Chen (2024) noted that digital finance can help to mitigate the unfavorable impact of natural resources rent on environmental sustainability. Equally important in nature is the realization that robust institutions characterized by effective governance, law enforcement, regulatory quality, and corruption control can enhance the utilization of natural resources (Oskenbayev, Yilmaz & Abdulla, 2013). This action may help to maintain a sustainable environment. Mohsen Mehrara, Alhosseini and Bahramirad (2008), also reenforced that robust and strong institutions can transform the resource curse into a blessing. Empirically, Nwani and Adams (2021) argued that robust institutional infrastructure is instrumental for curbing the unsustainable outcomes of natural resources rent. Conversely, weak governing institutions lacking transparency and law enforcement can lead to mismanagement and greenwashing practices, which will increase the unsustainable use of natural resources. Keeping this in consideration, we have incorporated Fig. 2 to present the comprehensive theoretical framework of the study.

Natural resources rent and environmental riskThe academic literature examining the impact of natural resources rent and environmental outcomes presents a two-fold picture and remains largely inconclusive. For example, in the context of BRICS and emerging nations, Adebayo et al. (2023) and A Jahanger, Usman and Ahmad (2023) argued that natural resources rent tends to substantially improve environmental performance. At the same time, in the context of the USA, Zafar et al. (2019) claimed that utilizing natural resources exerts a favorable impact on the environment. Saud, Haseeb, Zafar and Li (2023) linked natural resources rent with enhanced environmental sustainability in the MENA countries. Yan Sun et al. (2024) disclose that environmental sustainability is enhanced by utilizing natural resources rent using a sample of 17 countries. At another instance, (Razzaq, Wang, Adebayo & Al-Faryan, 2022) illustrated a negative relationship between natural resources rent and environmental contamination for European countries.

Conversely, several studies demonstrated unfavorable environmental outcomes of the natural resources rent. For instance, Caglar, Zafar, Bekun and Mert (2022) found that utilizing natural resources leads to an increase in the CO2 emissions, particularly in the context of BRICS countries. Moreover, (Alhassan & Kwakwa, 2023) noted that there is an adverse impact of natural resources rent on environmental sustainability. At another instance, Qing, Li, Mehmood and Dagestani (2024) claimed that natural resource rent hampers ecological sustainability in the G20 countries. For resource-rich countries, Ni, Yang and Razzaq (2022) show that natural resources deteriorate the sustainability of the environment. For China, Usman, Ozkan, Adeshola and Eweade (2024) also concluded that natural resources harm ecological sustainability. Furthermore, Okere et al. (2025) utilized data from 1991 to 2022 to investigate the impact of natural resources rent, FinTech, and globalization on environmental degradation in North Africa. The outcomes obtained through Augmented Mean Group (AGM) revealed that FinTech reduces environmental degradation, while the rent of natural resources and globalization tend to increase. As mentioned above, the literature presents conflicting results regarding the favorable and unfavorable environmental outcomes of natural resource rent. However, considering the above discussion, we have proposed the following hypothesis:

H1 Natural resources rent significantly affects (increases/decreases) environmental risk in the top 27 polluting countries.

The academic literature regarding the moderating role of FinTech in the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk is relatively scant. It can be claimed that a limited number of studies have examined the interconnectedness between FinTech, natural resources, and CO2 emissions. At the same time, several of these studies have yielded mixed results regarding the direct relationship between FinTech development and environmental outcomes. For BRICST and G7 economies, Ma, Destek, Shahzad and Bashir (2024) noted that FinTech development substantially improves environmental performance. Further dwelling into the literature, Vu, Bui, Pham and Vo (2024) concluded that FinTech development mitigates CO2 emissions in the context of 42 leading economies. Similar findings were reported by X. Feng, Zhou and Hussain (2024)) regarding G20 economies. Conversely, Lisha et al., 2023 found unfavorable environmental outcomes of FinTech within the BRICS economies. Other than that, Liu et al. (2024) also claimed a positive association between FinTech and CO2 emissions. Similarly, J. Ali et al. (2024) complement these findings and conclude that FinTech deteriorates environmental sustainability.

Furthermore, it can also be affirmed that FinTech's role in managing natural resources is instrumental for mitigating environmental risk. Using data from the years pertaining to 2012 to 2022, in the context of India, Tiwari (2024) found that FinTech can foster the sustainable utilization of natural resources. Moreover, Xu et al. (2024) also argued that FinTech can facilitate streamlining funds for green finance projects, which are essential to reducing CO2 emissions. In more precise terms, with the perspective of 13 resource-rich countries from 2013 to 2020, Khan et al. (2024) concluded that the establishment of FinTech can mitigate the carbon curse effect of natural resources utilization. From China, J. Chen and Chen (2024) also studied the impact of digital finance on the natural resources and the carbon neutrality nexus. The empirical outcomes through ARDL revealed that digital finance mitigates the adverse impact of natural resources on CO2 emissions. Therefore, based on the above literature, we propose the following hypothesis.

H2 FinTech can affect the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk in the top 27 polluting countries.

The debate in the literature about the influence of institutional quality on the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk is still experiencing growth and projection. The current literature predominantly focuses on the direct impact of institutional quality on environmental outcomes. For instance, A Jahanger et al. (2023) have taken into account a sample of 73 countries from 1990 to 2018 and found that institutional quality substantially reduces environmental contamination. In the context of E7, Bekun, Gyamfi, Köksal and Taha (2024) show that weak institutional quality tends to exacerbate environmental pollution. From 1984 to 2019, in the case of Pakistan, Hussain and Mahmood (2023) linked robust institutions with environmental sustainability. Similarly, by utilizing CS-ARDL from 1990 to 2018, Yunpeng Sun, Tian, Mehmood, Zhang and Tariq (2023) claimed that institutional quality positively influences environmental outcomes. Xaisongkham and Liu (2024), and Qayyum et al. (2024) investigated the interconnection between institutional quality and CO2 emission. Their findings categorically revealed that robust institutions are mandatory for decarbonization.

Besides the favorable environmental outcomes of robust institutions, these institutions also have the potential to mitigate the impact of natural resource rent on environmental risks. Following the same context, several studies shed light on the significance of robust institutions for the efficient and sustainable utilization of natural resources. For example, Oskenbayev et al. (2013) noted that strong institutions ensure transparency and accountability, particularly when it comes to the optimal utilization of natural resources. In their study, Mohsen Mehrara et al. (2008) stated that revenue from natural resources could be a blessing or a curse, mainly contingent on the quality of the institutions. Similarly, in the context of 43 countries from 1990 to 2022, Chung and Jin (2025)) claimed that the resource curse/blessing significantly depends on the quality of the institutions. In more specific and precise terms, Amiri, Samadian, Yahoo and Jamali (2019) noted the importance of robust governance infrastructure for the sustainable utilization of natural resources. In a sample of 93 countries with lower and higher governance quality from 1995 to 2017, Nwani and Adams (2021) investigated the linkage that existed between natural resources and CO2 emissions. The empirical estimates revealed that natural resources rent in countries with robust governance and institutions tends to mitigate the extent of CO2 emissions, while in countries with weak governance and institutions, it increases. Considering the above literature, we have proposed the following hypothesis:

H3 Institutional quality can affect the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk in the top 27 polluting countries.

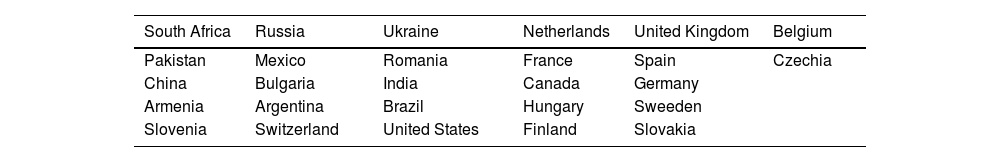

This study examines the moderating role of FinTech and institutional quality when it comes to the relationship between natural resource rent and environmental risk from 1995 to 2022, using a dataset of the top 27 polluting countries. The selection criteria for the top 27 polluting countries has been based on a reliable and consistent dataset in order to attain unbiased and reliable outcomes. Table 1 displays the list of selected countries. Moreover, this study has incorporated environmental risk as the dependent variable, while natural resources rent is the study's independent variable. The moderating variables are FinTech and institutional quality, while gross domestic product (GDP), financial globalization, and government intervention serve as the control variables in the study. The detailed definitions, variable code, and data sources are presented in Table 2. Lastly, due to different measurement units of the variables, we have taken the logarithm of all the variables to ensure that the dataset remains homogeneous.

Description of variables.

| Variables | Codes | Operational Definition | Ref. | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental risk | ERISK | The determination is made using the z-score of CO2 emissions, quantified in metric tons per capita. | (Kaewsaeng-on & Mehmood, 2024) | WDI |

| Natural resources rent | NNR | Total natural resources rents (% of GDP) | (Okere et al., 2025) | |

| Financial technology | FinTech | Demonstrates a financial technology index developed through PCA, encompassing the following indicators

| (Ul-Durar et al., 2025) | WDI & IMF |

| Institutional quality | IQ | Illustrates the institutional quality index calculated through PCA, encompassing the following indicators

| (Ul-Durar et al., 2025) | WGI |

| Natural resources rent* financial technology | NNR* FinTech | Interaction term | Author’s Computation | |

| Natural resources rent* institutional quality | NNR*IQ | Interaction term | Author’s Computation | |

| Gross domestic product | GDP | Gross domestic product constant to 2015 | (Alvarado & Toledo, 2017) | WDI |

| Financial globalization | FG | Represents the financial globalization index. | (R. Chen, Ramzan, Hafeez & Ullah, 2023) | KOF Swiss |

| Government intervention | GI | The ratio of final government expenditures to GDP. | (Ran, Liu, Razzaq, Meng, & Yang, 2023) | WDI |

Note: WDI shows “World Development Indicators”, IMF represents “International Monetary Fund”, WGI represents “World Governance Indicators”, and KOF Swiss represents the KOF Swiss Economic Institute.

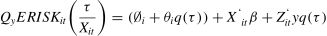

Following Atif Jahanger et al. (2024), we have derived Eq. (1) for the estimation.

ERISK, NNR, FinTech, IQ, NNR*FinTech, NNR*IQ, GDP, FG, and GI represent environmental risk, natural resources rent, financial technology, institutional quality, gross domestic product, financial globalization, and government intervention, respectively. Moreover, Eq. (2) shows the direct effect model, Eq. (3) presents the NNR and FinTech model, Eq. (4) displays the FinTech moderation effect model, Eq. (5) demonstrates the NNR and IQ model, and Eq. (6) signifies the IQ moderation effect model as follows.

Here, “i” indicates cross-sections, and “t” means the time. Furthermore, “ℇ_(i,t)” denotes the error term.

Empirical strategySubsequent parts of the study discuss the econometric technique, including descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, pre-estimation tests, benchmark regression, and robustness tests.

Cross-sectional dependence (CSD)In panel research, tackling cross-sectional dependency is the first essential step. In recent times, nations have been relying on one another due to financial convergence and globalization, which primarily accounts for cross-sectional dependence (Khalid & Shafiullah, 2021; J.-Z. Wang, Feng & Chang, 2024; L. Wang, Hafeez, Ullah & Yonter, 2023). Moreover, financial, social, and environmental elements have also been contributing towards cross-sectional dependence across nations (Menegaki, 2021). The projected outcomes lacking the CSD test would appear skewed and questionable. Therefore, this study has used Pesaran (2004) and Friedman (1937) tests to examine CSD. The subsequent equation illustrates the CSD test:

Slope homogeneity testThe current research has taken into account the Pesaran and Yamagata (2008) test to address the possible variability of slope variables produced from regression estimates across cross-sectional units owing to their differing socioeconomic features. According to the null hypothesis, this test approximates homogeneity using "Delta and Adjusted Delta" statistics. For this purpose, we have deployed the following equations.

Unit root testThe current study has selected the second-generation cross-sectional Im, Pesaran, and Shin unit root test (CIPS) as established by Pesaran (2007) to evaluate the unit root within the dataset over conventional unit root tests. The classic unit root tests may provide skewed conclusions because they rely on the supposition of cross-sectional dependency in the model. Nonetheless, the equation below is utilized for the CIPS test:

Here, V¯t−1 reveal cross-sectional averages. Additionally, the CADF also test uses the CIPS equation to ensure unit root accountability.

Cointegration testThe present study deployed the Pedroni (1999), Kao (1999), and Westerlund (2007) tests to evaluate the long-term connection among the variables. It must be noted that the Westerlund test can yield more reliable estimates while dealing with CSD and slope homogeneity. Furthermore, the Westerlund test can also accommodate different cross-sectional designs and time durations. The equation below is utilized to test the cointegration for that:

From the equation above, βi shows the error correction parameter, while ωi presents the vector parameter that links the cointegration between x and y.

Estimation technique MMQRIn the panel studies, heterogeneity is a constant issue that must be addressed. It raises questions regarding whether the predicted results are exaggerated by this heterogeneity, or are based on actual, pragmatic connections. Despite this information, most conventional panel estimating techniques are inefficient in handling this type of heterogeneity, which emphasizes the need for a more specialized approach.

Thus, this study has preferred a quantile-based estimation method to handle the issue of heterogeneity (Koenker & Bassett Jr, 1978). The development of quantile links can handle the heterogeneity in the dataset. Although quantile methods are grounded on suppositions of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), they produce unbiased and reliable outcomes by building a relationship with the quantiles. Furthermore, quantile-based methods are resistant to outliers. Also, traditional estimation methods generate outcomes on an average basis, while quantile methods provide comprehensive outcomes by establishing a link between the quantiles (Binder & Coad, 2011).

Additionally, this research has deployed the advanced Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) from the quantile fraternity. Apart from the above-stated advantages, MMQR can also shield against fixed-effect strikes (Machado & Silva, 2019). The MMQR is particularly preferred over other methods considering the following rationales. First, among the top 27 contaminated countries, the MMQR estimate approach can handle the distributional and heterogeneous changes that exist between environmental risk and selected explanatory variables. Second, MMQR provides objective, reliable, and efficient estimates under non-linear modelling.

The equation below demonstrates the location-scale variant of conditional quantiles.

Here, the τth quantile function condition is signified by ERISKit(τXit), and Xit displays the explanatory regressors as defined in Eq. (2). The scale and location functions are further written below:

Here, the scalar parameter representing the quantile fixed-effect is signified by ∅i+θiq(τ), while the Zi`=Zl`(X) shows the k-vector of known differentiable components of X with I elements. The explanatory variables in this approach do not reflect intercept changes, unlike in least squares fixed-effects. Heterogeneous impacts of these time-independent factors are allowed to vary throughout the quantile of the dependent variable's conditional distribution.

While, ρτ(A)=(τ−1)AI{A≤0}+TAI{A>0} displays the check function.

Robustness checkThe current investigation deployed Driscoll and Kraay standard errors (DKse) and Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) robustness assessment (Atif Jahanger et al., 2024). In this regard, The DKse method is assumed to be consistent against autocorrelation, heteroskedasticity, and temporal and common Cross-sectional dependency (Hoechle, 2007). In addition, the assumption of fixed effects in the DKse method can provide a shield against heterogeneity bias (Driscoll & Kraay, 1998; Hoechle, 2007). Besides that, FMOLS can examine the long-run cointegration among the dependent and independent variables, all while controlling endogeneity and serial correlation (Hansen & Phillips, 1988). Furthermore, the FMOLS can account for causal relationships while dealing with stationary errors, polynomial regression, and deterministic components (Pedroni, 2001a, 2001b).

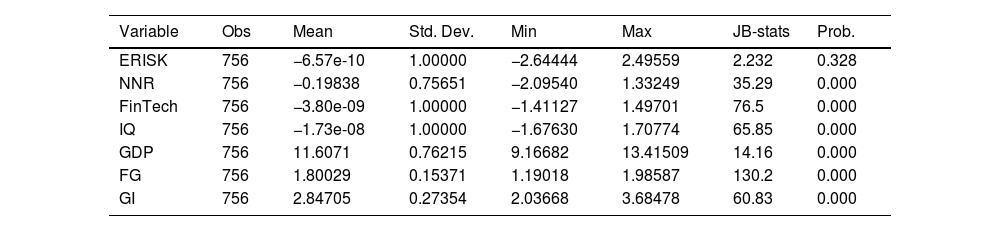

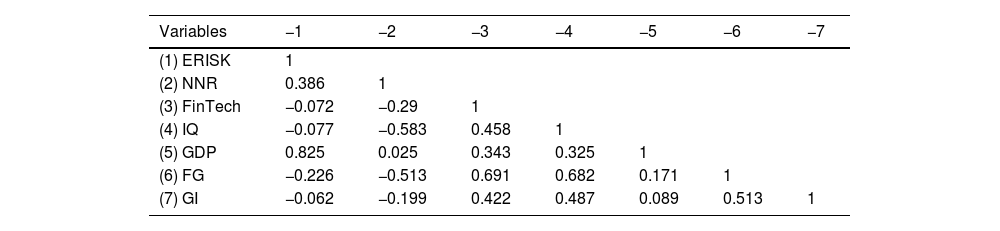

Results and discussionResultsThe first step of this analysis begins with descriptive statistics and JB test statistics in Table 3. The descriptive statistics present the standard deviation, mean, minimum, and maximum values for all the variables. The maximum, minimum, mean, and standard deviation of environmental risk are 2.49559, −2.64444, −6.57e-10, and 1.00000, respectively. The natural resources rent shows a mean value of −0.19838, followed by standard deviation, maximum, and minimum values of 0.75651, 1.33249, and −2.09540, respectively. The mean and standard deviation of FinTech are −3.80e-09 and 1.00000, respectively, while the maximum and minimum values are 1.49701 and −1.41127, respectively. The mean, standard deviation, maximum, and minimum values of institutional quality are −1.73e-08, 1.00000, 1.70774, and −1.167630, respectively. GDP shows 11.6071, 0.76215, 9.16682, and 13.41509 as the mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values, respectively. The mean and standard deviation of financial globalization are 1.80029 and 0.15371, respectively, with minimum and maximum values of 1.19018 and 1.98587, respectively. The mean, standard deviation, maximum, and minimum values of government intervention are 2.84705, 0.27354, 2.03668, and 3.68478, respectively. Furthermore, JB statistics show that all the variables, except for environmental risk, substantially deviate from the normal distribution pattern, thus making it legitimate to employ the MMQR methodology. Table 4 presents a correlation analysis, which validates that there is no perfect correlation between dependent and independent regressors.

Descriptive statistics.

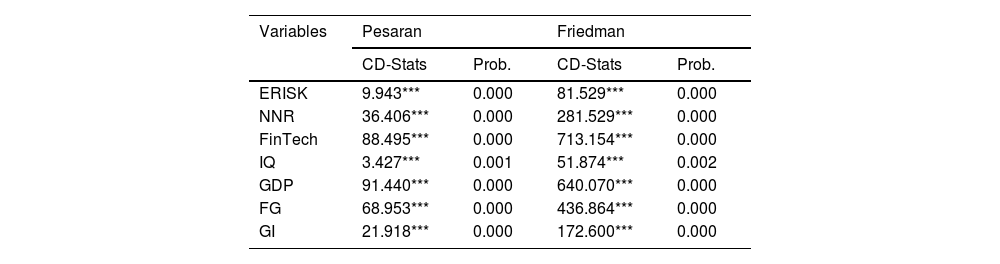

Table 5 illustrates the outcomes of the VIF test to examine the presence of multicollinearity between the selected variables. In this regard, the financial globalisation shows the highest VIF value of 3.20, followed by institutional quality, FinTech, natural resources rent, government intervention, and GDP, with values of 2.81, 2.21, 1.78, 1.53, and 1.39, respectively. The mean VIF value of 2.15 is under 10, indicating the absence of a multicollinearity issue in the dataset. Table 6 presents the CSD stats of the Pesaran and Friedman tests, which confirm cross-sectional dependence across all the variables. Furthermore, Table 7 shows the slope homogeneity test's Delta and Adjusted Delta values. At a 1 % statistical significance level, the outcomes validate the slope homogeneity across selected variables.

Cross-sectional dependency.

Note: *, ** & *** is for the significance level of 10 %, 5 % and 1 %.

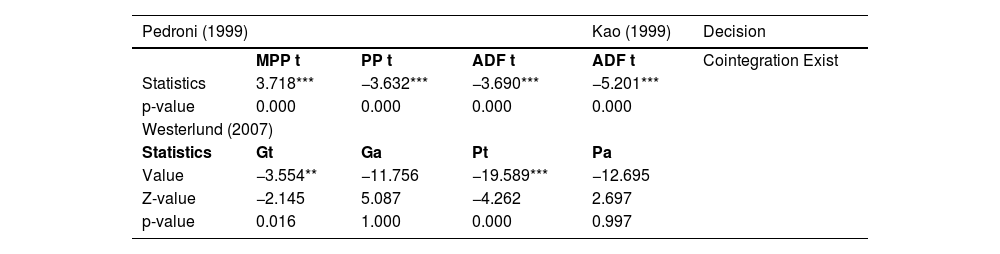

Table 8 displays the estimates of the CIPS and CADF unit root tests. According to reported outcomes, environmental risk, natural resources rent, and FinTech are stationary at the first difference, while other variables are stationary at the level. Similarly, CADF estimates confirm that environmental risk, FinTech, natural resources rent, and institutional quality are stationary at the first difference, while the other variables are stationary at the level. This outcome reflects the need to investigate the long run cointegration between the dependent and the independent regressors. Table 9 displays the estimates of the Kao, Pedroni, and Westerlund tests. The reported outcomes provide substantial evidence to declare cointegration among the variables. Nonetheless, the estimates of all pre-estimation tests validate proceeding further with the MMQR benchmark regression.

Panel unit root test.

Note: *, ** & *** is for the significance level of 10 %, 5 % and 1 %.

Panel cointegration test.

| Pedroni (1999) | Kao (1999) | Decision | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPP t | PP t | ADF t | ADF t | Cointegration Exist | |

| Statistics | 3.718*** | −3.632*** | −3.690*** | −5.201*** | |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Westerlund (2007) | |||||

| Statistics | Gt | Ga | Pt | Pa | |

| Value | −3.554** | −11.756 | −19.589*** | −12.695 | |

| Z-value | −2.145 | 5.087 | −4.262 | 2.697 | |

| p-value | 0.016 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.997 | |

Note: *, ** & *** is for the significance level of 10 %, 5 % and 1 %.

Table 10 presents the regression outcomes of all the models. Firstly, the direct effect model examines the influence of natural resources rent on environmental risk in the context of the top 27 contaminating countries. The empirical estimates have revealed a positive relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk. The positive nature of the relationship states that a 1 % increase in natural resources rent will increase the environmental risk by 0.204 %, 0.245 %, 0.307 %, 0.360 %, and 0.409 % at a 1 % statistical significance across all quantiles. Moreover, the coefficient values show an increasing trend, which further signifies that the rent from natural resources will substantially increase environmental risk in the long run. Also, it must be noted that the higher coefficient at the 90th quantile indicates that such countries are already exposed to higher environmental risks, and the natural resources rent can rapidly increase ecological stress as well. Furthermore, the control variable GDP across all quantiles and government intervention across the 50th, 75th, and 90th quantiles trigger environmental risk at a 1 % significance level. While the control variables such as financial globalisation, curbs environmental risk across all quantiles at a 1 % statistical significance level.

Benchmark regression.

Note: *, ** & *** is for the significance level of 10 %, 5 % and 1 %.

Secondly, the NNR and FinTech model investigate the combined impact of natural resources rent and FinTech on the environmental risk. The reported outcomes categorically demonstrate that every 1 % increase in natural resources rent will increase environmental risk by 0.231 %, 0.273 %, 0.323 %, 0.372 %, and 0.406 % at a 1 % significance level across all quantiles. The outcomes further show that FinTech negatively influences environmental risk across all quantiles at a 1 % significance level. More precisely, with every 1 % increase in FinTech, the environmental risk would be mitigated by −0.221 %, −0.248 %, −0.279 %, −0.310 % and −0.331 % across the 10th to 90th quantiles. The negative nature of this relationship signifies that FinTech is a viable factor in reducing environmental risk. Moreover, the coefficient values of FinTech show an increasing trend from the 25th to the 90th quantile. This increasing trend implies that FinTech plays an even stronger role in reducing the negative environmental impact of resource rents in countries that are already experiencing higher environmental risk.

Furthermore, control variable, GDP, across all quantiles and government intervention across the 25th quantile at 5 % and the 50th to 90th quantiles at a 1 % significance level trigger environmental risk. The control variable, financial globalisation, reduces environmental risk at the 25th quantile at the 5 % significance level and across the 50th to 90th quantiles at the 1 % significance level.

Thirdly, the FinTech moderation effect model examines the moderating role of FinTech in the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk. The reported estimates inferred that FinTech significantly and negatively moderates the relationship between natural resource rent and environmental risk. The negative nature of moderation implies that FinTech could be instrumental in mitigating unfavourable environmental outcomes of natural resources rent. The coefficient values of natural resources rent indicate that a 1 % increase in natural resources rent would raise the environmental risk by 0.237 %, 0.281 %, 0.326 %, 0.373 %, and 0.404 % across all quantiles at a 1 % significance level. The coefficients of FinTech imply that with every 1 % increase in FinTech, the environmental risk would be reduced by 0.246 %, 0.269 %, 0.292 %, 0.315 %, and 0.331 % at a 1 % significance level across all the quantiles. The interaction term coefficients (NNR*FinTech) across the 10th and 25th quantiles are −0.069 % and −0.056 % at a 10 % significance level, respectively. The coefficient value at the 50th quantile is −0.042 % at a 5 % significance level, while the 75th and 90th quantiles show insignificant coefficient values of −0.029 and −0.019, respectively. The significant coefficients across the 10th to 50th quantiles imply that FinTech can act as a strong force to reduce the negative environmental impact of the natural resources rent. Nonetheless, the insignificant coefficient values across the 75th and 90th quantiles suggest that FinTech alone may not be sufficient to reduce the negative environmental impact of resource rent in countries that are prone to experiencing higher environmental risk. Additionally, control variables, GDP, across all quantiles, and government intervention—specifically, across the 25th quantile at 5 % and the 50th to 90th quantiles at a 1 % significance level—exacerbate environmental risk. The control variable, financial globalisation, reduces environmental risk at the 25th quantile at the 5 % significance level and across the 50th to 90th quantiles at the 1 % significance level.

Fourthly, the NNR and IQ model analyse the combined impact of natural resources rent and institutional quality on environmental risk. The reported outcomes precisely illustrate that every 1 % increase in natural resources rent increases environmental risk by 0.140 %, 0.178 %, 0.230 %, 0.277 % and 0.318 % at a 1 % significance level across all the quantiles. The outcomes show that institutional quality negatively influences environmental risk across all quantiles at a 1 % significance level. The results categorically revealed that with every 1 % increase in institutional quality, the environmental risk would diminish by 0.131 %, 0.141 %, 0.156 %, 0.169 %, and 0.180 % across the 10th to 90th quantiles. The negative nature of this relationship signifies that institutional quality is a mandatory factor when it comes to the reduction of environmental risk. Moreover, the coefficient values of institutional quality show an increasing trend from the 25th to the 90th quantile. This increasing trend implies that institutional quality plays an even stronger role in reducing the negative environmental impact of resource rents in countries that are already experiencing higher environmental risk. Furthermore, control variables, such as GDP, across all quantiles and government intervention across the 25th to 90th quantiles, at a 1 % significance level, increase environmental risk. The control variable, financial globalisation, decreases environmental risk across all the quantiles at a 1 % statistical significance level.

Lastly, the IQ moderation effect model examines the moderating role of institutional quality in the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk. The findings show that FinTech significantly and negatively moderates the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk. The negative nature of moderation implies that institutional quality could be instrumental in mitigating unfavourable environmental outcomes of natural resources rent. In this regard, the coefficient values of natural resources rent show that a 1 % increase in natural resources rent would increase environmental risk by 0.153 %, 0.192 %, 0.244 %, 0.291 % and 0.332 % across all the quantiles, at a 1 % significance level. The coefficients of FinTech imply that with every 1 % increase in institutional quality, the environmental risk would be mitigated by 0.145 %, 0.148 %, 0.152 %, 0.156 %, and 0.159 % at a 1 % significance level across all the quantiles. Moreover, the interaction term (NNR*IQ) coefficient at the 25th quantile is −0.040 % at a 10 % significance level. While the coefficient values across the 50th and 90th quantiles are at a −0.050 % and −0.065 % at a 5 % significance level, respectively. Furthermore, the coefficient value at the 75th quantile is −0.059 % at a 1 % significance level, while the 10th quantile shows the insignificant coefficient value of −0.033 %. Notably, the significant negative impact of the interaction term is found across the 50th to 90th quantiles, indicating that for countries at a moderate to higher level of environmental risk, institutional quality serves as a robust factor in reducing adverse environmental externalities from natural resource rent. Moreover, control variables, GDP across all quantiles, and government intervention—specifically, across the 25th quantile at 5 % and the 50th to 90th quantiles at a 1 % significance level—exacerbate environmental risk. The control variable pertaining to financial globalisation, mitigates environmental risk at the 10th quantile at the 5 % significance level, and across the 25th to 90th quantiles at the 1 % significance level. Fig. 3 presents the 3D surface plots of MMQR estimates.

Robustness analysisThe benchmark findings of MMQR are endorsed through the Dkse and FMOLS estimation methods in Table 11. The robustness findings have yielded similar results. However, a substantial variation in the magnitude of the coefficients has been reported in the robustness findings. The direct effect model shows that the rent of natural resources substantially increases environmental risk. The combined effect models, such as NNR and FinTech, and NNR and IQ models, revealed a positive relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk, while FinTech and institutional quality substantially mitigate the environmental risks. Finally, both the moderation effect models illustrate that FinTech and institutional quality can mitigate the adverse environmental outcomes of natural resources rent across the 27 polluting countries that have been taken into account.

Robustness check.

Note: *, ** & *** is for the significance level of 10 %, 5 % and 1 %.

This current research primarily analyses the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk, in the presence of FinTech and institutional quality measures, in the top 27 contaminating countries. The primary findings reveal that the rent from natural resources drives an increase in CO2 emissions, one of the significant environmental risks around the globe. The over-extraction and unsustainable utilisation of natural resources, such as fossil fuels, pose severe environmental risks. The natural resource rents adversely affect nuclear energy development while economic growth and trade, also hinder nuclear growth (Luan et al., 2025). Moreover, the forest resources and bio-energy technology considerably stimulate green growth (Zhao et al., 2025). This outcome is consistent with H1 of the study, which states that the natural resources rent significantly increases environmental risk. Several studies before this have also demonstrated that natural resources rent substantially increases the concentration of CO2 emissions in the atmosphere, thus increasing environmental risk (Ni et al., 2022; Okere et al., 2025). Also, in the same regard, FinTech is found to be instrumental for reducing environmental risk across 27 polluting countries. This implies that FinTech can streamline funding for green and sustainable projects by eliminating the gap between finance providers and their clients. Digital and information technologies and mineral resources could also prove to be vital in the transition towards low-carbon energy frameworks (Liu et al., 2025). FinTech uses technology to eliminate traditional and unsustainable practices, a factor that is crucial for mitigating environmental risk. Several studies support the claim of our research that rests on the premise that FinTech can substantially reduce CO2 emissions in order to mitigate environmental risk (Ma et al., 2024; Vu et al., 2024). In addition to this, institutional quality is found to be a strong force in mitigating environmental risks. This outcome essentially sheds light on the importance of robust institutions in implementing sustainable strategies. It is noteworthy that strong institutions can establish a vibrant and transparent system, develop environmental protection laws, and ensure compliance through accountability and penalties. Several studies have reported similar outcomes that link strong institutions with CO2 emission reduction in order to mitigate environmental risk (Hussain & Mahmood, 2023; A Jahanger et al., 2023).

Moreover, FinTech negatively moderates and mitigates the unfavourable environmental outcomes of natural resources rent. This outcome is consistent with H2 of our research, thus implying that FinTech significantly affects the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk. In this regard, it can be affirmed that FinTech can promote the efficient and sustainable management and utilisation of natural resources. Besides that, FinTech can help channel funds for eco-friendly projects and technologies to diminish CO2 emissions in the atmosphere. These arguments align with prior the studies' outcomes (Tiwari, 2024). In addition to this, J. Chen and Chen (2024) also noted that establishing digital financial platforms can mitigate the adverse environmental outcomes of natural resources extraction. Lastly, institutional quality negatively moderates and diminishes the adverse environmental effect of natural resources rent. This result is adjacent to H3, which states that institutional quality significantly affects the relationship between the rent of natural resources and environmental risk. It is noteworthy that this outcome complements several prior studies. For instance, Oskenbayev et al. (2013) show that strong and influential institutions can control the over-extraction and unsustainable utilisation of natural resources. Furthermore, Mohsen Mehrara et al. (2008) noted that strong institutions can ensure sustainable management of resources, while weak institutions can trigger the resource curse. Also, robust institutions and effective governance can eliminate undue influence, thus enabling the implementation of stringent environmental laws and policies on the extraction and utilization of natural resources. The findings of Nwani and Adams (2021) are consistent with these arguments that countries with strong governance levels are better positioned to utilize natural resources for favorable environmental outcomes.

Conclusion, policy implications, and limitationsConclusionEnvironmental risk is a pressing global concern, particularly with increasing environmental threats exerting pressure on institutions, individuals, and governing think tanks. When there is excessive extraction and unsustainable utilization of natural resources, it is common for CO2 emissions to experience a sharp incline in the atmosphere and therefore increase environmental risk. To prevent this, SDG 13 of the UN calls for immediate action against climate change and environmental risk. From this perspective, FinTech and IQ could ensure the efficient utilization of natural resources to prevent the adverse effects that they have on environmental outcomes. Despite the substantial theoretical significance of FinTech and institutional quality, prior studies have largely overlooked how they can mitigate or exacerbate the adverse effect of natural resources rent on the environmental risk. Therefore, this research aims to address this literature gap by investigating the moderating role of FinTech and institutional quality in the relationship between natural resources rent and environmental risk. The study deployed a novel MMQR estimation method to run an empirical analysis in the top 27 polluting countries from the years pertaining to1995 to 2022. The empirical findings have concluded that natural resources rent is primarily responsible for increasing environmental risk, while FinTech and institutional quality mitigate it. Moreover, FinTech and institutional quality negatively moderate the impact of natural resources rent on environmental risk. The study's outcomes also conclude that FinTech and institutional quality are instrumental factors that can help mitigate the unfavorable environmental impact of natural resources rent. The control variables, GDP and government intervention, are found to be contributors to environmental risk, while financial globalization can mitigate it. The robustness analysis through DKse and FMOLS shows similar outcomes, thus confirming the benchmark findings of MMQR. Despite these findings, the magnitude of the Dkse and FMOLS coefficients varies substantially from the coefficients of MMQR.

Policy implicationsBased on the aforementioned outcomes of this research, the following policies concerning environmental risk mitigation have been articulated. First, natural resources rent is the primary driver of environmental risk in the top polluting countries. Policymakers and think tanks should enforce taxes on heavy-polluting industries that extract natural resources. This can aid in the encouragement of efficient and sustainable utilization of natural resources. Second, our results indicate that FinTech can mitigate the effect of natural resources rent on environmental risk across 27 polluting countries. In this regard, the governments should introduce a digital green investment platform, blockchain technology, and a FinTech-based transparency mechanism to bridge the gap between natural resource rent and sustainable projects. For instance, countries like China, Russia, India, America, Germany, Brazil, Spain, and Sweden should assist FinTech firms by offering incentives to companies that use digital payments and incorporating FinTech into public services in order to actively reduce paper-based transactions and the need for physical infrastructure. This could aid in the optimal and efficient management and utilization of natural resources, as well as the transition of funds towards green and environmentally friendly projects. Third, the outcomes revealed that robust institutions have the capability to mitigate the negative environmental impacts of natural resource rent. Therefore, governing authorities and think tanks should develop a transparent and robust institutional structure, establish corruption control strategies, and ensure political stability and governance effectiveness. The government think tanks should encourage transparent revenue reporting frameworks, environmental auditing, and monitoring agencies in countries like South Africa, Russia, Pakistan, Ukraine, and India, where inefficient governing institutions amplify environmental risk. In parallel with these measures, the government should establish stringent environmental policies and set quotas for natural resource extraction in order to ensure efficient and sustainable utilization. Fourth, the empirical outcomes found that in countries with high levels of contamination, FinTech may not be fully capable of mitigating the negative environmental impact of natural resource rent. Therefore, top polluting regions such as BRICS should encourage FinTech advancement and foster a robust institutional culture simultaneously to effectively bridge resource rent and sustainable practices.

Limitations and future research directionsAlthough the outcomes of this study provide actionable policy implications, they are also attributed to several shortcomings that future empirical studies could address. Though we have applied a novel MMQR estimation method, which is efficient in capturing heterogeneous effects across several quantiles. Nonetheless, the relationship between FinTech, institutional quality, natural resources rent, and environmental risk could be subject to a potential endogeneity issue. Therefore, we recommend that future empirics employ dynamic panel estimation methods for more robust empirical evidence of causal relationships. Moreover, in macroeconomic studies, nonlinear modelling is considered to be a superior methodology as compared to linear modelling. Therefore, future empirics can avoid this limitation to present more reliable estimates. We also acknowledge the measurement limitations of institutional quality and the FinTech index and recommend future investigations by incorporating micro-level FinTech data and diverse governance indicators. We have incorporated CO2 emissions as a significant environmental risk, but this may not depict a broader picture. Therefore, future studies can consider other environmental risks, such as ocean acidification, deforestation rates, load capacity factors, and soil degradation. Future studies can also draw a comparative analysis by subdividing the sample into developing and developed regions. Lastly, our study overlooked examining the impact of COVID-19 on environmental risks, which could be a crucial research avenue for future empirical studies.

CRediT authorship contribution statementXuefeng Shao: Supervision, Software, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Chengming Hu: Visualization, Supervision, Conceptualization. Manal Yunis: Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Conceptualization. Lulu Hao: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.