A profound review of the literature on entrepreneurship reveals that it does not exist a specific information tool to measure the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship. The purpose of this research has been building such kind of instrument to estimate the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship. Its design takes in consideration the inclusion of the main variables identified by the literature as those most associated with entrepreneurial profiles. These variables have been grouped into three categories: sociological, psychological and managerial-entrepreneurial. Each group provides batteries of items which are evaluated thanks to a specific scoring system. The final objective is to provide a system to calculate individual scores of readiness for entrepreneurship and, at the same time, partial scores on concrete aspects of it. The information tool is presented at this paper and will be tested and refined in the near future.

La profunda revisión de la literatura asociada al análisis del fenómeno emprendedor pone de manifiesto la inexistencia de una herramienta de información específica para medir la disposición de las personas para emprender. El propósito de esta investigación ha sido el de diseñar un instrumento capaz de estimar la disposición de las personas hacia el emprendimiento. Su confección tiene en cuenta la inclusión de las principales variables identificadas por la literatura como aquellas más estrechamente relacionadas con los perfiles emprendedores. Estas variables han sido agrupadas en tres categorías: sociológicas, psicológicas y correspondientes al ámbito de la gestión empresarial. Cada grupo proporciona baterías de ítems evaluables gracias a un sistema específico de puntuación. El objetivo final es el de ofrecer un sistema capaz de calcular puntuaciones individuales de disposición para el emprendimiento y, simultáneamente, puntuaciones parciales sobre aspectos concretos de dicha disposición. La herramienta de información se presenta en este artículo y será probada, contrastada y refinada en un futuro próximo.

Entrepreneurship is crucial for having a healthy and rich economic structure characterized by high well-being levels (Saiz-Álvarez, Coduras, & Cuervo-Arango, 2014). The most dynamic countries in the world are characterized by the quality and quantity of their entrepreneurship, especially when expansive fiscal policies are limited, consumption is reduced, and investment (both foreign and domestic) is reluctant. As a result, the labor market is negatively affected in terms of higher unemployment and poverty generation, so it will be desirable to design a tool for measuring the readiness for entrepreneurship.

According to the existing literature concerning entrepreneurship, there is a range of psychological factors rooted on entrepreneurial education (Chen et al., 2015; Jiménez, Palmero-Cámara, González-Santos, González-Bernal, & Jiménez-Eguizábal, 2015; Oehler, Hoefer, & Schalkowski, 2015; Piperopoulos & Dimov, 2015; Rauch & Hulsink, 2015; Saeed, Yousafzai, Yani-de-Soriano, & Moreno, 2015), need for achievement (Begley & Boyd, 1987) and working experience (Moog, Werner, Houweling, & Backes-Gellner, 2015); social factors based on gender (Bullough, de Luque, Abdelzaher, & Heim, 2015; Langevang, Gough, Yankson, Owusu, & Osei, 2015; Radhakrishnan, 2015), age (Harms, Luck, Kraus, & Walsh, 2014; Hatak, Harms, & Fink, 2015; Ouimet & Zarutskie, 2014), balanced entrepreneurial skills (Lazear, 2004), ability to interact with others (Baron, 2000) and family (Oezcan, 2011; Dunn & Holtz-Eakin, 2000); economic variables mainly grounded on corporate design, as decentralized structures are associated with opportunity realization of new business opportunities (Foss, Lyngsie, & Zahra, 2015), business strategy (Block, Kohn, Miller, & Ullrich, 2015), rurality (Ranjan, 2015), and immigration (Coduras, Saiz-Álvarez, & Cuervo-Arango, 2013). All these factors psychological, social, and economic variables interact in the desire to start a new business.

The objective of this paper is to propose a new instrument to measure the readiness for entrepreneurship. The importance for designing an information tool to measure the entrepreneur's availability to undertake is multiple: first, this instrument has interest to potential entrepreneurs so they know which is the ideal time to undertake; second, measuring the readiness for entrepreneurship facilitates the realization of job-generating economic policies, and, third, this instrument can improve the economic and social welfare in a country, regardless of their level of development. To cope with this goal, we begin defining the term “readiness for entrepreneurship” and we analyze its composition formed by sociological, psychological and entrepreneurial/economic variables. This will allow us to theoretically design and propose the instrument. Finally, we establish some conclusions and some future research lines will be drawn.

Readiness for entrepreneurship: definition and compositionA single definition is essential for measuring readiness for entrepreneurship as measuring a poorly defined concept would be impossible. To design and develop the information tool proposed in this paper, we adopt the following definition for readiness for entrepreneurship which constitutes one of the results achieved during the first stage of this research.

Definition (Ruiz, Ribeiro, & Coduras, 2016): The readiness for entrepreneurship of individuals is defined as the confluence of a set of personal traits (or features) that distinguishes individuals with readiness for entrepreneurship as especially competent to observe and analyze their environment in such a way that they channel their high creative and productive potential, so they may deploy their capability to dare and need for self-achievement.

Complementing the previous definition, the theoretical framework built around this concept at the first stage of this research, lead to the following conclusion regarding the internal composition of an individual's readiness for entrepreneurship: The readiness for entrepreneurship is determined by a wide set of sociological, psychological, and business management factors. Each of these disciplines provides measurable qualitative and quantitative variables that have been linked in scientific research to entrepreneurship and in entrepreneurial personality and behavior, and that must be considered in the theoretical framework to develop a tool for measuring readiness for entrepreneurship.

From the previous conclusion it is clear that a tool to measure individual's readiness for entrepreneurship must include a wide set of items related with three essential fields: personal/family-based characteristics, economic/entrepreneurial background, and a set of psychological traits. The next sections provide the selected items within each and the justification for their inclusion in the design.

What should the proposed tool aspire to measure?The proposed tool should aspire to measure the degree in which the set of personal treats and specific features that distinguish individuals with readiness for entrepreneurship are present for an individual.

This aspiration implies the inclusion of sets of items related to the three main pillars that compose a personality ready for entrepreneurship: sociological, psychological and specific entrepreneurial traits.

The next sections expose the selected items for each one of these three pillars to integrate the information tool and the justification for their inclusion.

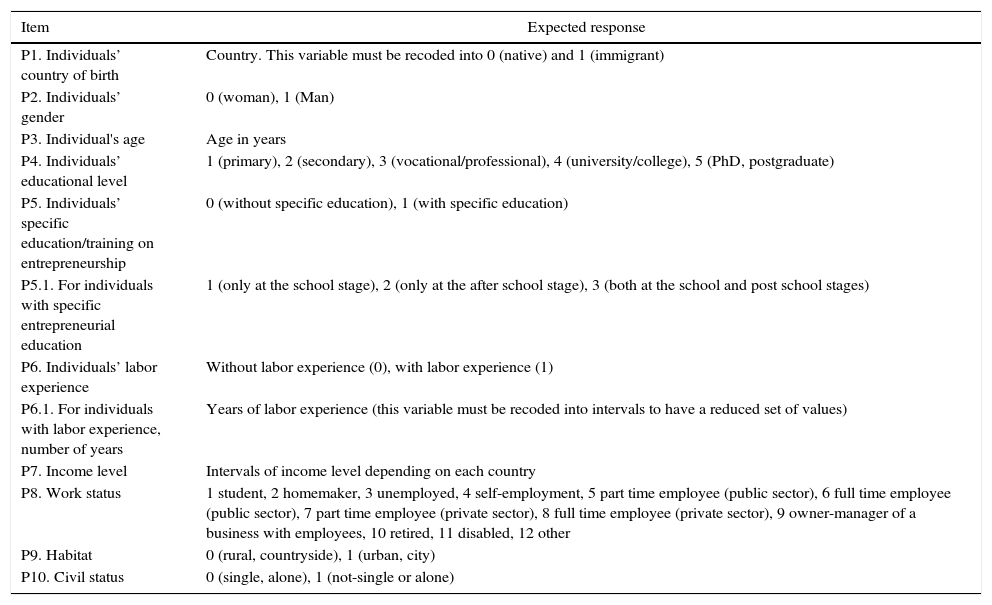

The contribution of items related to sociological characteristics for measuring the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurshipThe selected items related to sociological characteristics for measuring the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship have been and are widely studied regard their relationship with entrepreneurship. These items are showed in Table 1.

Proposed items related to personal characteristics for measuring the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship.

| Item | Expected response |

|---|---|

| P1. Individuals’ country of birth | Country. This variable must be recoded into 0 (native) and 1 (immigrant) |

| P2. Individuals’ gender | 0 (woman), 1 (Man) |

| P3. Individual's age | Age in years |

| P4. Individuals’ educational level | 1 (primary), 2 (secondary), 3 (vocational/professional), 4 (university/college), 5 (PhD, postgraduate) |

| P5. Individuals’ specific education/training on entrepreneurship | 0 (without specific education), 1 (with specific education) |

| P5.1. For individuals with specific entrepreneurial education | 1 (only at the school stage), 2 (only at the after school stage), 3 (both at the school and post school stages) |

| P6. Individuals’ labor experience | Without labor experience (0), with labor experience (1) |

| P6.1. For individuals with labor experience, number of years | Years of labor experience (this variable must be recoded into intervals to have a reduced set of values) |

| P7. Income level | Intervals of income level depending on each country |

| P8. Work status | 1 student, 2 homemaker, 3 unemployed, 4 self-employment, 5 part time employee (public sector), 6 full time employee (public sector), 7 part time employee (private sector), 8 full time employee (private sector), 9 owner-manager of a business with employees, 10 retired, 11 disabled, 12 other |

| P9. Habitat | 0 (rural, countryside), 1 (urban, city) |

| P10. Civil status | 0 (single, alone), 1 (not-single or alone) |

The series of items begins with the individuals’ origin, as several studies (Aldrich, Jones, & McEvoy, 1984; Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990; Light, Bhachu, & Karageorgis, 2004; Mancilla, Viladomiu, & Guallarte, 2010; Min & Bozorgmehr, 2000; Portes, Guarnizo, & Haller, 2002 & many more) have demonstrated that immigrants use to be proportionally more entrepreneurial than natives in a wide range of countries. Among these studies stands out the 2012 GEM Global Report (Xavier, Kelley, Kew, Herrington, & Vorderwülbecke, 2012) as it devoted a wide section to describe the immigrant entrepreneurial activity worldwide.

The second item is gender. The literature gives support to a higher male participation in entrepreneurship and to some behavioral differences regarding the readiness for entrepreneurship between men and women (Bullough et al., 2015; Kelley, Brush, Greene, & Litovsky, 2013 & many more). At this respect, Langevang et al. (2015) draw the notion of mixed embeddedness to explore how time-and-place specific institutional contexts influence differences in gender to decide for entrepreneurship, and they find State regulations and cultural-cognitive institutional forces as the main obstacles for women's entrepreneurial business success. This situation is especially strong when women are poor, as social variables (mainly gender, social class, and cultural adaptation to changes) play a key role in rural (Ranjan, 2015) and traditional societies in Third World countries (Radhakrishnan, 2015). The third item is age. Some empirical studies based on individual data have found an inverse U-shaped relationship between age and the decision to start a business (Bönte, Falck, & Heblich, 2009), while other findings suggest that the age-specific likelihood of becoming an entrepreneur changes with the size of the age cohort, pointing to the existence of age-specific peer effects. The literature gives different visions about the relevance of the age and its relationship with the entrepreneurial activity depending on countries’ features, the labor market status and others but, in general it is accepted that middle aged individuals’ are more prone to start-up new ventures (Casserly, 2013), with the exception of highly developed societies where experienced and adult professionals (gray entrepreneurship) are active entrepreneurs by leaving paid employment to become self-employed (Harms et al., 2014; Blanchflower, 2004). Moreover, whereas gender, education, and previous entrepreneurial experience matter, as well as intuition (Saiz-Álvarez, Cuervo-Arango, & Coduras, 2013). Hatak et al. (2015) find that leadership and having entrepreneurial parents seem to have no impact on the entrepreneurial intention of employees. Finally, and complementary to ambition (Oehler et al., 2015), age is important for new firm creation as, according to Ouimet and Zarutskie (2014), an increase in the supply of young workers is positively related to new firm creation in high-tech industries, supporting a causal link between the supply of young workers and new firm creation.

The fourth item is education. Recent studies demonstrate that individuals’ educational level uses to show a negative correlation with entrepreneurship but also depending on the countries’ development stage. Necessity entrepreneurs tend to have less educational level than opportunity entrepreneurs. Wennekers, Thurik, and Reynolds (2002) explained the causes that justify these trends this way: “For the most advanced nations, improving incentive structures for business start-ups and promoting the commercial exploitation of scientific findings offer the most promising approach for public policy. Developing nations, however, may be better off pursuing the exploitation of scale economies, fostering foreign direct investment and promoting management education”. Other studies show that tertiary education has a negative effect on informal entrepreneurship, as it increases awareness of and sensitivity to the possible negative repercussions of this kind of activities (Jiménez et al., 2015).

The fifth item is about the possession of specific entrepreneurial education. GEM studies (Coduras, Levie, Kelley, SÆmundsson, & SchØtt, 2008) demonstrate a positive correlation between the possession of entrepreneurial education and training and the interest for entrepreneurship as a professional option. In this regard, perceived educational support exerts the highest influence on entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention, and on concept, business and institutional development support (Saeed et al., 2015). Complementary to these findings, Piperopoulos and Dimov (2015) show that higher self-efficacy is associated with lower entrepreneurial intentions in the theoretically oriented courses and higher entrepreneurial intentions in the practically oriented courses. This fact is especially improved when there is a mentor co-teaching who enhances satisfaction toward the course and the learning efficacy of students (Chen et al., 2015), and when antecedents of intentions and behavior are increased (Rauch & Hulsink, 2015).

The sixth item introduces the labor experience in the readiness for entrepreneurship measurement as the literature points out that individuals with managerial experience (Reynolds, 1997) or who are experts on concrete activity sectors (Shane, 2000) are more prone to start-up new ventures. Also, there are studies which demonstrate the relationship between early work experience and the possession of entrepreneurial spirit (Colombatto & Melnik, 2007), and the importance of being in contact with entrepreneurial peers (Moog et al., 2015)

The seventh item is about personal income. Studies performed during the eighties (Evans & Jovanovic, 1989) stated that individuals with greater assets are more likely to switch into self-employment, all else equal. This result is still consistent with the view that entrepreneurs face liquidity constraints. In principle, wealthier individuals could make better entrepreneurs or could have accumulated wealth in the prospect of starting a business. Therefore, a positive correlation between wealth and the propensity to become an entrepreneur is not definitive evidence of binding liquidity constraints. Evans and Jovanovic (1989) tackled this issue using a structural model with predictions on the relation between the level of entrepreneurial earnings and initial assets, and the proportion of assets that more and less constrained entrepreneurs invest in their own businesses. They found that entrepreneurs with more initial assets earned a higher entrepreneurial income, suggesting that they could run businesses with a more efficient level of capital. Moreover, poorer individuals now and then, tend to devote a larger fraction of their wealth to their businesses, suggesting that liquidity constraints are indeed binding. Studies are not conclusive regard the income level and its relationship with entrepreneurship but the general perception has not changed substantially across time. Currently, GEM, for example, associates lower levels of income with necessity entrepreneurs and higher levels of income with opportunity entrepreneurs. Other studies (Giannetti & Simonov, 2004) point out that income interacts with other variables in such a way that, for example, individuals are more likely to become entrepreneurs where there are more entrepreneurs, even if entrepreneurial income is lower. In conclusion, there is still much to investigate to this respect.

The eight item is work status. Following Kihlstrom and Laffont (1979), an individual's decision to become an entrepreneur “is the result of a maximization process in which the individual in question compares the returns from alternative income producing activities and selects the employment opportunity with the highest expected return”. Recent studies performed on GEM international individual data (Arenius & Minniti, 2005) showed that work status was not significant as working and non-working respondents appeared as equally likely to engage in nascent entrepreneurship, but the recent economic crises have been pushing unemployed people toward taking entrepreneurship as an alternative. Thus, it is possible that the perception regard the entrepreneurial option can have changed during the last decade being possible an increment of the readiness for entrepreneurship among unemployed, part time employees, students and/or other work status. Also the persistence of governments and media translating the necessity of increasing the entrepreneurial activity rate in most countries would have some influence in other work status categories.

The ninth item is habitat (rural versus urban). Some GEM studies stated some evidences that, at least in some countries, people living in rural areas is more entrepreneurial. This effect has been justified before (Dabson, 2001; Fornahl, 2003; Lafuente, Vaillant, & Rialp, 2007) through different arguments such as the necessity of rural zones of being provided with minimum services, the higher development of primary sector activities which are critical for urban areas, the diversity of entrepreneurial opportunities out of the big cities and others. Rural entrepreneurship is especially affected by local resilience (Steiner & Atterton, 2015) mainly affecting small-scale food-related rural firms, as this type of food-related entrepreneurship affects consumption and value creation (Arthur & Hracs, 2015). Finally, value creation is fostered when entrepreneurship is rooted, at least partially, on technology (Wallis, 2015).

The last variable of this group is civil status. This variable is interesting due to women's possible constraints derived of their civil status and family life depending on the age as stated in the GEM special reports on women entrepreneurship (Kelley et al., 2013). Moreover, skill-spillover between partners might be context dependent and only from men to women (Oezcan, 2011).

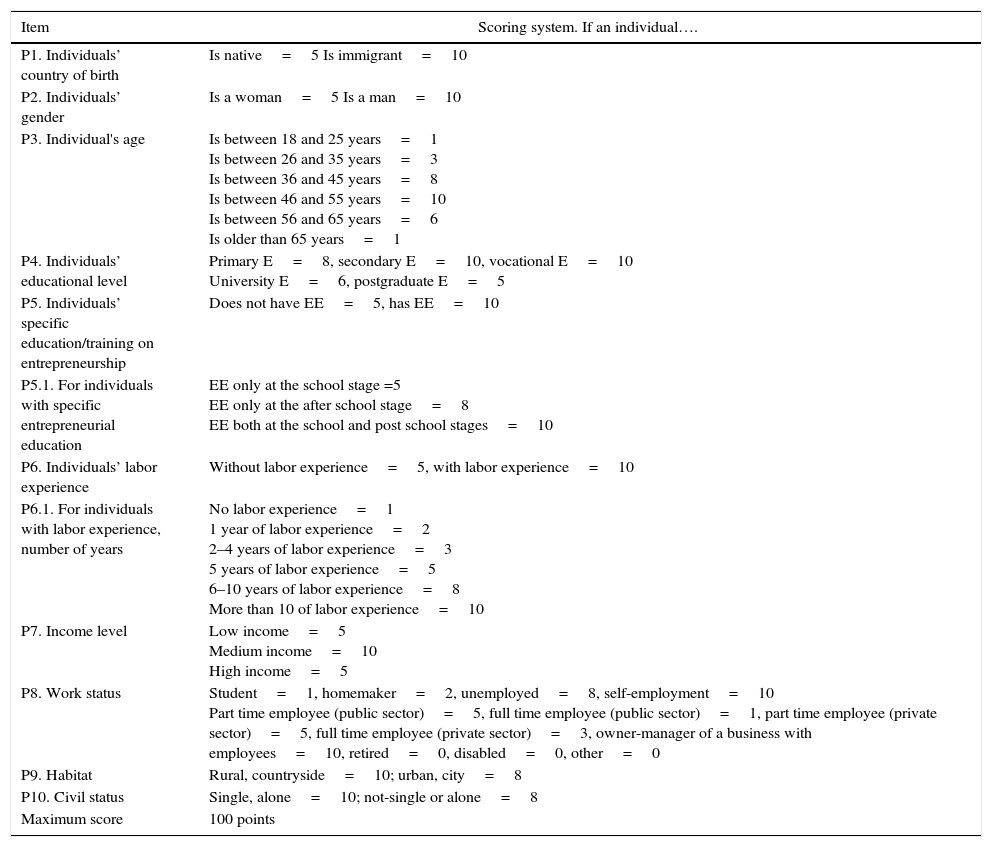

Once selected the items of this group, the next step consisted in assigning scores to each one to quantify the contribution of personal traits to readiness for entrepreneurship. The scoring system (see Table 2) has been designed taking into account the conclusions provided by the literature on each item and the type of impact expected (higher or lower) on the evaluated concept. The scoring system for sociological features contributes to the total score with a maximum of 100 points being:

100=maximum score of readiness for entrepreneurship from the sociological perspective

99–80=high score of readiness for entrepreneurship from the sociological perspective

79–50=medium score of readiness for entrepreneurship from the sociological perspective

49-or low=low score of readiness for entrepreneurship from the sociological perspective

Proposed scoring for items related to personal characteristics for measuring the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship.

| Item | Scoring system. If an individual…. |

|---|---|

| P1. Individuals’ country of birth | Is native=5 Is immigrant=10 |

| P2. Individuals’ gender | Is a woman=5 Is a man=10 |

| P3. Individual's age | Is between 18 and 25 years=1 Is between 26 and 35 years=3 Is between 36 and 45 years=8 Is between 46 and 55 years=10 Is between 56 and 65 years=6 Is older than 65 years=1 |

| P4. Individuals’ educational level | Primary E=8, secondary E=10, vocational E=10 University E=6, postgraduate E=5 |

| P5. Individuals’ specific education/training on entrepreneurship | Does not have EE=5, has EE=10 |

| P5.1. For individuals with specific entrepreneurial education | EE only at the school stage =5 EE only at the after school stage=8 EE both at the school and post school stages=10 |

| P6. Individuals’ labor experience | Without labor experience=5, with labor experience=10 |

| P6.1. For individuals with labor experience, number of years | No labor experience=1 1 year of labor experience=2 2–4 years of labor experience=3 5 years of labor experience=5 6–10 years of labor experience=8 More than 10 of labor experience=10 |

| P7. Income level | Low income=5 Medium income=10 High income=5 |

| P8. Work status | Student=1, homemaker=2, unemployed=8, self-employment=10 Part time employee (public sector)=5, full time employee (public sector)=1, part time employee (private sector)=5, full time employee (private sector)=3, owner-manager of a business with employees=10, retired=0, disabled=0, other=0 |

| P9. Habitat | Rural, countryside=10; urban, city=8 |

| P10. Civil status | Single, alone=10; not-single or alone=8 |

| Maximum score | 100 points |

Entrepreneurs are individuals who have abilities to see and understand “things entrepreneurial” better than non-entrepreneurial do (Douglas, 2009). These abilities could be acquired because an individual was born to entrepreneurial parents and learned entrepreneurial attitudes and abilities from them while others could acquire this knowledge at the educational system or at the work place.

The literature defends that knowing entrepreneurs increases the entrepreneurial background as the individual is exposed to examples but, despite these influences, these individuals may possess specialized knowledge and idiosyncratic resources such that risks perceived by others do not apply to them because of their higher human entrepreneurial capital (Janney & Dess, 2006).

Entrepreneurs tend to perceive opportunities differently and also to perceive themselves as more competent than non-entrepreneurs, that is, they tend to have higher self-efficacy or confidence in that they can accomplish a specific task or set of tasks (Krueger & Dickson, 1994). This confidence may be based on their possession of superior knowledge about an entrepreneurial opportunity, due to a higher knowledge regard the market needs and/or the technological potential for serving those needs (Gifford, 2003). In addition, entrepreneurs tend to show overconfidence in their abilities (Simon, Houghton, & Aquino, 2000), a higher preference than non-entrepreneurs on non-monetary outcomes (Douglas and Shepherd, 2000) and are less risk averse (Gifford, 2003; Krueger & Dickson, 1994). In addition to the previous, Davidsson and Honig (2003), found that social capital variables (having parents in business, being encouraged by friends, having neighbors or friends who are entrepreneur and having social network) have significant impact to launch new ventures. Also, Brockhaus and Horwitz (1986) along with other authors found that entrepreneurs tend to make decisions with less information than other managers, while access to risk capital is important for creating start-ups (Blanchflower and Oswald, 1998).

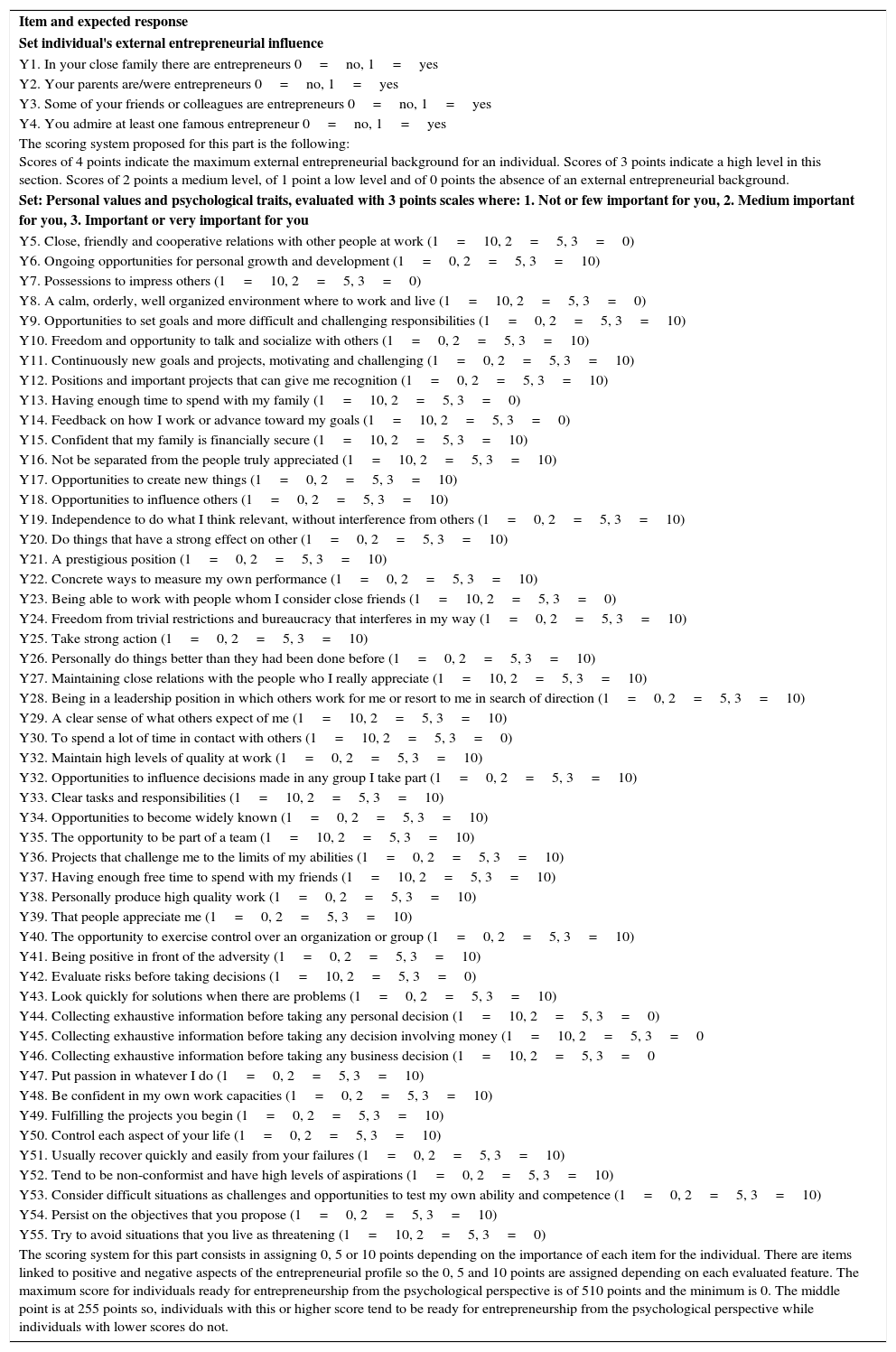

Passion, positivism, sacrifice capacity, abilities to convince others, empathy, good communication capacity, leadership and skills to conduct work teams complete the set of main features associated to entrepreneurs by most of the mentioned authors. Table 3 shows the concrete proposal to measure the selected features as ingredients to identify individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship form the psychological perspective.

Proposed items and scoring system related to psychological traits for measuring the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship.

| Item and expected response |

| Set individual's external entrepreneurial influence |

| Y1. In your close family there are entrepreneurs 0=no, 1=yes |

| Y2. Your parents are/were entrepreneurs 0=no, 1=yes |

| Y3. Some of your friends or colleagues are entrepreneurs 0=no, 1=yes |

| Y4. You admire at least one famous entrepreneur 0=no, 1=yes |

| The scoring system proposed for this part is the following: Scores of 4 points indicate the maximum external entrepreneurial background for an individual. Scores of 3 points indicate a high level in this section. Scores of 2 points a medium level, of 1 point a low level and of 0 points the absence of an external entrepreneurial background. |

| Set: Personal values and psychological traits, evaluated with 3 points scales where: 1. Not or few important for you, 2. Medium important for you, 3. Important or very important for you |

| Y5. Close, friendly and cooperative relations with other people at work (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| Y6. Ongoing opportunities for personal growth and development (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y7. Possessions to impress others (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| Y8. A calm, orderly, well organized environment where to work and live (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| Y9. Opportunities to set goals and more difficult and challenging responsibilities (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y10. Freedom and opportunity to talk and socialize with others (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y11. Continuously new goals and projects, motivating and challenging (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y12. Positions and important projects that can give me recognition (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y13. Having enough time to spend with my family (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| Y14. Feedback on how I work or advance toward my goals (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| Y15. Confident that my family is financially secure (1=10, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y16. Not be separated from the people truly appreciated (1=10, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y17. Opportunities to create new things (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y18. Opportunities to influence others (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y19. Independence to do what I think relevant, without interference from others (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y20. Do things that have a strong effect on other (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y21. A prestigious position (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y22. Concrete ways to measure my own performance (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y23. Being able to work with people whom I consider close friends (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| Y24. Freedom from trivial restrictions and bureaucracy that interferes in my way (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y25. Take strong action (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y26. Personally do things better than they had been done before (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y27. Maintaining close relations with the people who I really appreciate (1=10, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y28. Being in a leadership position in which others work for me or resort to me in search of direction (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y29. A clear sense of what others expect of me (1=10, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y30. To spend a lot of time in contact with others (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| Y32. Maintain high levels of quality at work (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y32. Opportunities to influence decisions made in any group I take part (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y33. Clear tasks and responsibilities (1=10, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y34. Opportunities to become widely known (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y35. The opportunity to be part of a team (1=10, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y36. Projects that challenge me to the limits of my abilities (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y37. Having enough free time to spend with my friends (1=10, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y38. Personally produce high quality work (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y39. That people appreciate me (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y40. The opportunity to exercise control over an organization or group (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y41. Being positive in front of the adversity (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y42. Evaluate risks before taking decisions (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| Y43. Look quickly for solutions when there are problems (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y44. Collecting exhaustive information before taking any personal decision (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| Y45. Collecting exhaustive information before taking any decision involving money (1=10, 2=5, 3=0 |

| Y46. Collecting exhaustive information before taking any business decision (1=10, 2=5, 3=0 |

| Y47. Put passion in whatever I do (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y48. Be confident in my own work capacities (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y49. Fulfilling the projects you begin (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y50. Control each aspect of your life (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y51. Usually recover quickly and easily from your failures (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y52. Tend to be non-conformist and have high levels of aspirations (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y53. Consider difficult situations as challenges and opportunities to test my own ability and competence (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y54. Persist on the objectives that you propose (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Y55. Try to avoid situations that you live as threatening (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| The scoring system for this part consists in assigning 0, 5 or 10 points depending on the importance of each item for the individual. There are items linked to positive and negative aspects of the entrepreneurial profile so the 0, 5 and 10 points are assigned depending on each evaluated feature. The maximum score for individuals ready for entrepreneurship from the psychological perspective is of 510 points and the minimum is 0. The middle point is at 255 points so, individuals with this or higher score tend to be ready for entrepreneurship from the psychological perspective while individuals with lower scores do not. |

The readiness for entrepreneurship evaluation should be completed scoring the possession of concrete skills and experiences associated to the development of an entrepreneurial career. The next section is devoted to the selection of this type of items and their proposed scoring system.

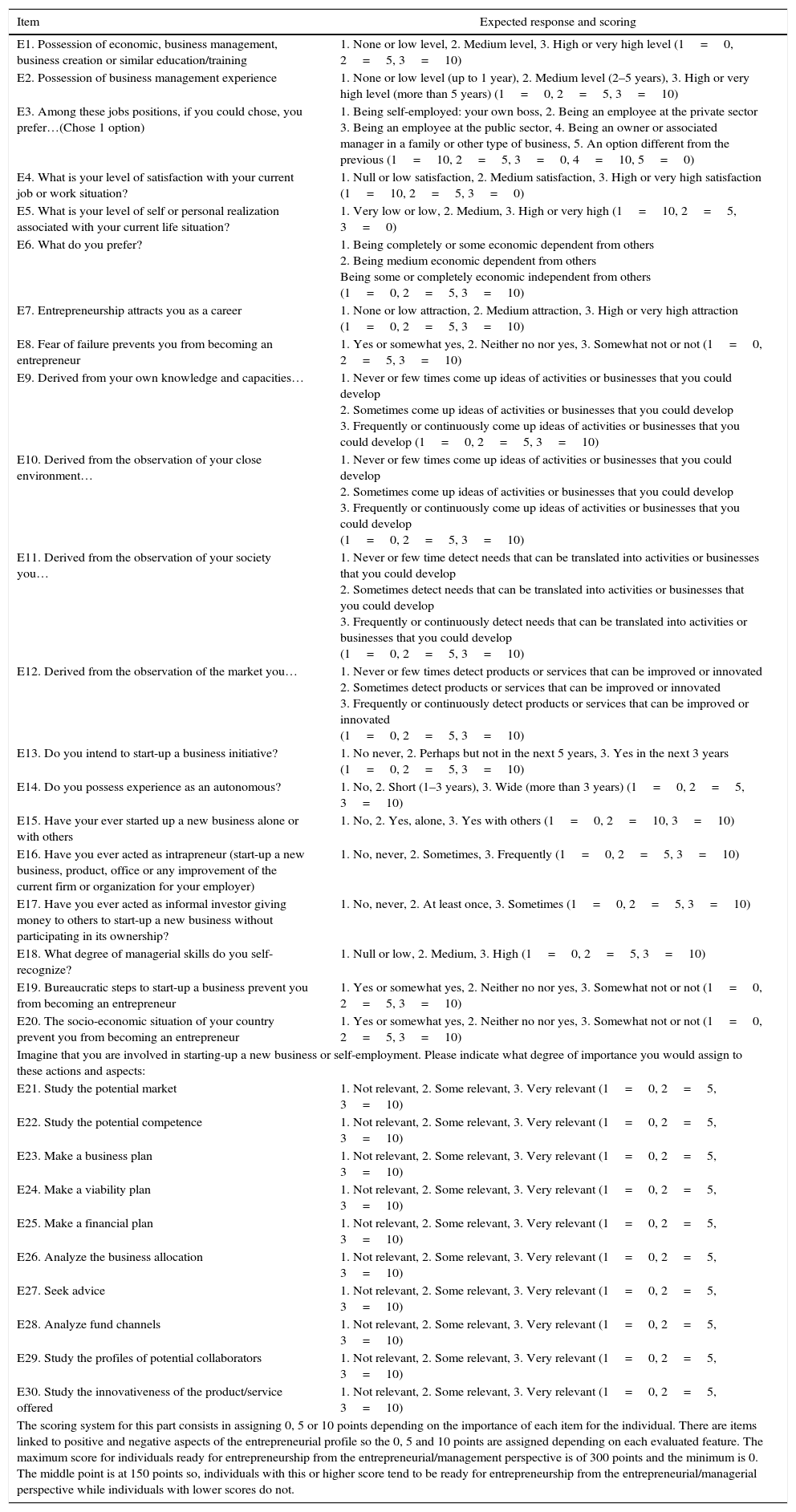

The contribution of items related to entrepreneurial and managerial background for measuring the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurshipThis section presents the items selected to evaluate the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship from the perspective of their possession of entrepreneurial capacity and experience, management skills, necessity of change, capacity for opportunities recognition, and other related aspects (see Table 4). The adequateness of these items for their inclusion in the information tool is justified in the next paragraphs.

Proposed items and their scoring system related to entrepreneurial/managerial background for measuring the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship.

| Item | Expected response and scoring |

|---|---|

| E1. Possession of economic, business management, business creation or similar education/training | 1. None or low level, 2. Medium level, 3. High or very high level (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E2. Possession of business management experience | 1. None or low level (up to 1 year), 2. Medium level (2–5 years), 3. High or very high level (more than 5 years) (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E3. Among these jobs positions, if you could chose, you prefer…(Chose 1 option) | 1. Being self-employed: your own boss, 2. Being an employee at the private sector 3. Being an employee at the public sector, 4. Being an owner or associated manager in a family or other type of business, 5. An option different from the previous (1=10, 2=5, 3=0, 4=10, 5=0) |

| E4. What is your level of satisfaction with your current job or work situation? | 1. Null or low satisfaction, 2. Medium satisfaction, 3. High or very high satisfaction (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| E5. What is your level of self or personal realization associated with your current life situation? | 1. Very low or low, 2. Medium, 3. High or very high (1=10, 2=5, 3=0) |

| E6. What do you prefer? | 1. Being completely or some economic dependent from others 2. Being medium economic dependent from others Being some or completely economic independent from others (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E7. Entrepreneurship attracts you as a career | 1. None or low attraction, 2. Medium attraction, 3. High or very high attraction (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E8. Fear of failure prevents you from becoming an entrepreneur | 1. Yes or somewhat yes, 2. Neither no nor yes, 3. Somewhat not or not (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E9. Derived from your own knowledge and capacities… | 1. Never or few times come up ideas of activities or businesses that you could develop 2. Sometimes come up ideas of activities or businesses that you could develop 3. Frequently or continuously come up ideas of activities or businesses that you could develop (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E10. Derived from the observation of your close environment… | 1. Never or few times come up ideas of activities or businesses that you could develop 2. Sometimes come up ideas of activities or businesses that you could develop 3. Frequently or continuously come up ideas of activities or businesses that you could develop (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E11. Derived from the observation of your society you… | 1. Never or few time detect needs that can be translated into activities or businesses that you could develop 2. Sometimes detect needs that can be translated into activities or businesses that you could develop 3. Frequently or continuously detect needs that can be translated into activities or businesses that you could develop (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E12. Derived from the observation of the market you… | 1. Never or few times detect products or services that can be improved or innovated 2. Sometimes detect products or services that can be improved or innovated 3. Frequently or continuously detect products or services that can be improved or innovated (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E13. Do you intend to start-up a business initiative? | 1. No never, 2. Perhaps but not in the next 5 years, 3. Yes in the next 3 years (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E14. Do you possess experience as an autonomous? | 1. No, 2. Short (1–3 years), 3. Wide (more than 3 years) (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E15. Have your ever started up a new business alone or with others | 1. No, 2. Yes, alone, 3. Yes with others (1=0, 2=10, 3=10) |

| E16. Have you ever acted as intrapreneur (start-up a new business, product, office or any improvement of the current firm or organization for your employer) | 1. No, never, 2. Sometimes, 3. Frequently (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E17. Have you ever acted as informal investor giving money to others to start-up a new business without participating in its ownership? | 1. No, never, 2. At least once, 3. Sometimes (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E18. What degree of managerial skills do you self-recognize? | 1. Null or low, 2. Medium, 3. High (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E19. Bureaucratic steps to start-up a business prevent you from becoming an entrepreneur | 1. Yes or somewhat yes, 2. Neither no nor yes, 3. Somewhat not or not (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E20. The socio-economic situation of your country prevent you from becoming an entrepreneur | 1. Yes or somewhat yes, 2. Neither no nor yes, 3. Somewhat not or not (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| Imagine that you are involved in starting-up a new business or self-employment. Please indicate what degree of importance you would assign to these actions and aspects: | |

| E21. Study the potential market | 1. Not relevant, 2. Some relevant, 3. Very relevant (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E22. Study the potential competence | 1. Not relevant, 2. Some relevant, 3. Very relevant (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E23. Make a business plan | 1. Not relevant, 2. Some relevant, 3. Very relevant (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E24. Make a viability plan | 1. Not relevant, 2. Some relevant, 3. Very relevant (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E25. Make a financial plan | 1. Not relevant, 2. Some relevant, 3. Very relevant (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E26. Analyze the business allocation | 1. Not relevant, 2. Some relevant, 3. Very relevant (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E27. Seek advice | 1. Not relevant, 2. Some relevant, 3. Very relevant (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E28. Analyze fund channels | 1. Not relevant, 2. Some relevant, 3. Very relevant (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E29. Study the profiles of potential collaborators | 1. Not relevant, 2. Some relevant, 3. Very relevant (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| E30. Study the innovativeness of the product/service offered | 1. Not relevant, 2. Some relevant, 3. Very relevant (1=0, 2=5, 3=10) |

| The scoring system for this part consists in assigning 0, 5 or 10 points depending on the importance of each item for the individual. There are items linked to positive and negative aspects of the entrepreneurial profile so the 0, 5 and 10 points are assigned depending on each evaluated feature. The maximum score for individuals ready for entrepreneurship from the entrepreneurial/management perspective is of 300 points and the minimum is 0. The middle point is at 150 points so, individuals with this or higher score tend to be ready for entrepreneurship from the entrepreneurial/managerial perspective while individuals with lower scores do not. | |

To date, entrepreneurship knowledge has been more associated with individuals’ possessing economic education or background. This is not determinant for readiness for entrepreneurship but recent studies (Wadhwa, Holly, Aggarwal, & Salkever, 2009) pointed out that one of the significant barriers to start-up effectively is the lack of business and/or management skills so, it seems logical to consider the possession of these abilities as a positive factor for readiness for entrepreneurship.

Another relevant point is the influence of the work status on the readiness for entrepreneurship. In a study carried out during the last eighties, Evans and Leighton (1989) found, using US data, that the probability of switching into self-employment appears as roughly independent of the total labor market experience. Additionally, their data demonstrated that poorer wage workers—that is, unemployed workers, lower-paid wage workers, and individuals who have changed jobs a lot—are more likely to enter into self-employment, thereby corroborating the idea that “misfits” are pushed into entrepreneurship.

Other topics have been widely studied thanks to GEM data. The GEM project adopted items related with the attraction of entrepreneurship as professional career, the fear of failure as a burden to consider starting-up new ventures, the possession of entrepreneurial skills and experience, the entrepreneurial intentions and aspirations and others plenty justified previously by the literature and identified by GEM principal investigators within it. Some of them have been adapted to be part of this section of the proposed information tool.

Final remarks and future lines of researchNo holistic, scientifically grounded tool to measure readiness for entrepreneurship exists, yet there are numerous entrepreneurial capacity tests with no rigorous scientific grounding. As a remedy, this paper provides a solid and scientific-based development of a valid instrument for measuring readiness for entrepreneurship.

A complex tool able to identify and measure readiness for entrepreneurship would be applicable in numerous situations, including the following by: [1] determining entrepreneurial abilities, [2] analyzing potential for entrepreneurship, [3] simulating organizational transformations, and [4] evaluating investment recommendations.

The current work offers a new, holistic perspective of readiness for entrepreneurship measurement. The research addresses the measurement of readiness for entrepreneurship from a rigorous, scientific approach. The main implication lies in offering a useful and necessary tool for the entrepreneurship framework that is currently in expansion. Different agents can use this tool to measure individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship. These include educators, business angels, associations, venture capitalists, business managers, entrepreneurship developers, Chief Executive Officers (CEO), bankers, and independent potential entrepreneurs, among other.

The main result of this effort is the provision of a proposed information tool to measure the individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship. The tool is composed by different groups of items which include the main variables considered by the literature as more associated with this concept. Of course the research team is conscious about the limitations of this tool as it is impossible cover completely all the determinants of readiness for entrepreneurship but the team considers that it can be a good and useful approximation.

The tool is composed by a group of items about sociological characteristics, a second group about psychological treats and a third group about entrepreneurial and managerial background. Each group is evaluated thanks to a concrete scoring system. This system has been designed taking in consideration the literature and the general conclusions extracted by prestigious researchers regard the scope and sign of each possible response. However, the goodness of fit of this system to provide individual scores and conclusions about individuals’ readiness for entrepreneurship is unknown. That is why the next step will consist in testing the tool for a representative sample of individuals and evaluate its performance.

The future lines of research contemplate testing the information tool and refine it before proceeding to its registration. Several trials are planned and different groups of individuals will participate in them: from students to current people to real entrepreneurs, different profiles will be evaluated and compared. The results of these experiences will be presented in at least a new paper. The hope of this team is contribute to the progress of readiness for entrepreneurship measurement and offer a useful and refined tool to cover this purpose.