Despite broad support for sustainability, the transition from linear to circular economic models remains slow and fragmented across industries. Digital technologies such as the metaverse present new opportunities for enabling circular economy (CE) practices, yet their strategic integration within organizational systems is not fully understood. To address this gap, this study proposes and empirically validates a model that explains how metaverse adoption influences CE implementation through the mediating role of Immersive Knowledge Co-Creation (IKCC), and the moderating effect of Open Eco-Innovation Capability (OEIC). Grounded in the knowledge-based view (KBV), interactive learning theory, and dynamic capabilities theory, the research develops a process-driven and capability-oriented framework to explore the mechanisms and boundary conditions for digital-enabled circular transformation. Empirical data were collected from 220 respondents in Germany's advanced manufacturing sector and analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling. The results confirm that IKCC significantly mediates the relationship between metaverse adoption and CE implementation, and that this mediated relationship is stronger in firms with high OEIC. These findings contribute to the growing body of literature on digital innovation in the CE by highlighting the critical role of immersive collaboration and organizational readiness in driving circular processes.

In recent years, the concept of the circular economy (CE) has emerged as a critical response to the growing environmental crisis and the limitations of traditional, linear production models (Rejeb et al., 2023). Unlike the linear “take-make-dispose” economy, the CE promotes a regenerative system designed to minimize waste, extend product lifecycles, and optimize resource use (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Kirchherr et al., 2017). This paradigm shift is increasingly viewed as essential for achieving the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals, particularly those related to responsible consumption and environmental sustainability (United Nations, 2015). However, despite its theoretical appeal, the practical transition from linear to circular systems remains slow and fragmented across industries. This is mainly due to systemic barriers such as technological inertia, lack of collaboration, and limited organizational readiness to adopt innovative and eco-sustainable practices (De Jesus & Mendonça, 2018; Kirchherr et al., 2017; Ranta et al., 2018). As such, enabling an effective and scalable transition toward the CE demands integrated frameworks that combine digital technologies, open innovation ecosystems, organizational capability development, and government support (Centobelli et al., 2022; Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014; Wang & Zhang, 2024a).

The academic discourse around CE has made significant progress in outlining strategies such as eco-design, closed-loop supply chains, and resource recovery systems (Bocken & Ritala, 2022; Camilleri, 2019; Rejeb, Suhaiza et al., 2022). Studies have also highlighted the importance of collaborative networks and technological integration for achieving CE outcomes (Centobelli et al., 2022; Lopes et al., 2017). However, much of the existing literature remains largely conceptual or focused on isolated industry cases, offering limited insights into how CE principles can be systematically applied across diverse organizational settings (De Jesus & Mendonça, 2018; Jaeger & Upadhyay, 2020). Furthermore, while many scholars acknowledge the role of innovation in driving circularity (Cassetta et al., 2023; Kennedy et al., 2017), there is still a lack of knowledge regarding how organizations facilitate the shift from awareness to practical implementation. Notably, existing research often overlooks the dynamic, process-oriented aspects of organizational collaboration, learning, and transformation that are essential for embedding circular practices within firms (Eisenreich et al., 2021; Köhler et al., 2022).

In response to digital transformation trends, emerging research has turned attention toward the metaverse as a potentially powerful enabler of sustainable innovation (Dwivedi et al., 2022; Piccarozzi et al., 2024). These studies have highlighted its potential for stakeholder engagement, 3D modeling, virtual product lifecycle management, data analytics and planning, warehousing and inventory management, and simulation of circular systems (Lyu & Fridenfalk, 2023; Papamichael et al., 2023; Treiblmaier, 2025). However, much of this literature remains technocentric, focusing primarily on the tools themselves rather than the organizational and behavioral conditions under which they succeed (Köhler et al., 2022). Current work does not sufficiently explore the processes through which immersive platforms enable collaborative innovation or how diverse actors come together within these environments to co-develop sustainable solutions (Jesus & Jugend, 2023). Furthermore, the literature lacks attention to the variation in organizational readiness that may affect the ability to leverage these tools effectively (Jaeger & Upadhyay, 2020; Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, 2009). Without a profound investigation into the interactional dynamics and organizational contexts that shape the adoption of the metaverse, its role in advancing circular economy initiatives cannot be fully realized. Similarly, there is a need to move beyond tool-centric views to unlock the transformative potential of the metaverse and comprehend how digital immersion intersects with collaboration, leadership, and innovation capability.

To overcome the conceptual and practical limitations in the current literature, this study proposes that metaverse adoption can serve as a powerful digital enabler for CE implementation when leveraged as a platform for immersive collaboration. The metaverse introduces unique capabilities such as spatial simulation, virtual co-presence, and real-time 3D interaction that extend far beyond traditional communication tools (Dwivedi et al., 2022). These capabilities create fertile ground for shared learning and dynamic stakeholder engagement, which are often missing in unidirectional knowledge transfer models (Camilleri, 2019; Radianti et al., 2020). They enable firms and their partners to explore complex sustainability challenges together, visualize circular systems, and co-develop solutions in a virtual setting (Eisenreich et al., 2021; Jesus & Jugend, 2023). The value of this process lies not merely in technological adoption but in how it transforms collaboration into mutual value creation. Therefore, we argue that the process of immersive, participatory knowledge exchange is the critical pathway through which metaverse adoption contributes to the realization of CE goals. This mediating process is conceptualized in this study as Immersive Knowledge Co-Creation (IKCC).

While immersive platforms such as the metaverse offer tremendous potential for collaborative sustainability innovation, their effectiveness is highly contingent on the organizational environment in which they are deployed (Köhler et al., 2022; Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, 2009). Not all firms are equally equipped to harness the metaverse for meaningful knowledge co-creation. Some may lack the digital infrastructure, innovation-oriented culture, or openness to external partnerships required to translate immersive interactions into strategic outcomes (Jaeger & Upadhyay, 2020; Vial, 2021). This variance highlights the need to consider an organization’s openness to external knowledge flows in addition to its capacity to integrate digital and environmental innovations (Bogers et al., 2020; De Medeiros et al., 2014). To address this, we introduce a novel construct that combines digital preparedness and open innovation orientation with an eco-sustainability lens. This capability reflects a firm’s ability not only to adopt immersive technologies but also to fully engage in collaborative circular innovation. It is this combination that enables organizations to activate and amplify the knowledge co-creation potential of the metaverse. Accordingly, we conceptualize this as a moderating variable, named Open Eco-Innovation Capability (OEIC), which influences the strength of the relationship between metaverse adoption and IKCC. Building on the above conceptual arguments and identified gaps, this study formulates the following research questions to explore the mechanisms and boundary conditions through which metaverse adoption influences CE implementation.

RQ1: How does the adoption of metaverse technologies influence CE Implementation in organizational settings?

RQ2: What role does IKCC play in mediating the relationship between metaverse adoption and CE Implementation?

RQ3: How does OEIC moderate the relationship between metaverse adoption and IKCC?

By addressing these questions, this study makes a timely and meaningful contribution to the emerging intersection of CE, digital innovation, and collaborative strategy. By conceptualizing how metaverse technologies can facilitate immersive stakeholder collaboration, the research addresses a critical gap in understanding the operational mechanisms that enable CE implementation. Furthermore, by introducing IKCC as a mediating process and OEIC as a moderating condition, the study offers a nuanced framework that explains both how and under what conditions immersive technologies foster the implementation of the CE. This integrated perspective not only enriches the theoretical discourse on digital-enabled circular transformation but also provides practical insights for policymakers, innovation leaders, and sustainability practitioners aiming to foster collaborative, technology-driven pathways toward a circular future. As such, the research responds directly to the call for frameworks that bridge technological potential with organizational action in advancing the green transition (Geissdoerfer et al., 2018).

To empirically ground this study, Germany was selected as the research context due to its global leadership in sustainability initiatives and industrial innovation (Horvat et al., 2025). As a pioneer in implementing the European Green Deal and advancing CE regulations, Germany provides a robust policy environment that actively supports the transition toward circular practices (BMUV, 2022; European Commission, 2020). Furthermore, the country’s advanced manufacturing sector, which includes automotive, industrial equipment, electronics, and smart factory systems, offers an ideal setting to explore the integration of immersive digital technologies with sustainable operations (Müller et al., 2018). These industries are particularly relevant because they are both resource-intensive and innovation-driven, making them highly suitable for examining the use of technologies such as digital twins, virtual collaboration environments, and 3D simulations (BMWK, 2021). This unique combination of environmental commitment and technological capability positions Germany’s manufacturing sector as a strategically appropriate context for investigating how immersive collaboration can accelerate the implementation of CE principles.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on CE, immersive technologies, and innovation capabilities, highlighting theoretical foundations and research gaps. Section 3 presents the conceptual framework and development of hypotheses. Section 4 outlines the research methodology, including data collection, sampling, and measurement procedures. Section 5 reports the empirical results, before Section 6 discusses the theoretical and practical implications of the key findings. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper by outlining the study’s limitations and suggesting directions for future research.

Literature reviewCircular economyThe CE has gained prominence as a strategic framework to address growing environmental challenges by focusing on minimizing waste, enhancing resource efficiency, reducing environmental deterioration, and fostering regenerative production models (Chirumalla et al., 2024; Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Kayikci et al., 2022, 2024; Rejeb, Zailani et al., 2022). Extant literature has explored key CE strategies such as product-service systems, eco-design, remanufacturing, and reverse logistics (Bocken & Ritala, 2022; Camilleri, 2019). However, much of this research remains focused on static frameworks and lacks attention to the process-level mechanisms that enable CE principles to be applied across diverse industries (De Jesus & Mendonça, 2018; Jaeger & Upadhyay, 2020). Moreover, while collaboration and inter-organizational cooperation are acknowledged as critical to establish sustainable business practices (Wang & Zhang, 2024b), studies often overlook the interactive and dynamic nature of stakeholder engagement needed to operationalize circular strategies (Brown et al., 2019; Eisenreich et al., 2021). As a result, limited insight exists into how multi-actor engagement and organizational learning can support scalable and practical CE implementation within firms (Köhler et al., 2022; Lopes et al., 2017).

Metaverse and its role in the CERecent developments in the ongoing digital transformation have prompted scholars to consider how immersive technologies, particularly the metaverse, might support circular initiatives (Dwivedi et al., 2022; Piccarozzi et al., 2024). These technologies provide tools such as digital twins, simulations, and collaborative virtual spaces that can help parties to visualize and co-develop circular processes (Lyu & Fridenfalk, 2023; Papamichael et al., 2023). Although conceptually promising, the current body of work tends to be technology-focused, emphasizing use cases without adequately addressing how organizations engage in collaborative and experiential interaction within these virtual environments (Dwivedi et al., 2022; Mandal et al., 2025). Additionally, limited attention has been paid to the variation in organizational conditions, such as readiness, openness to innovation, or digital capability, that may affect how effectively immersive tools are adopted and integrated (Köhler et al., 2022; Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, 2009). These gaps require further inquiry into how organizations can translate digital immersion into meaningful knowledge sharing and actionable CE outcomes.

Immersive knowledge co-creationTo better understand how digital environments, such as the metaverse, might enable transformative sustainability outcomes, it is necessary to shift the focus toward the knowledge-based and interactive processes they facilitate. The KBV of the firm positions knowledge as the most strategically significant resource in a firm, emphasizing the creation, sharing, and integration of knowledge as core to innovation (Grant, 1996; Nonaka, 2009). Similarly, interactive learning theory highlights the role of socially embedded, iterative learning among diverse actors in generating meaningful innovation (Lundvall, 1992). Together, these theories suggest that immersive technologies have the potential to do more than just visualize circular systems since they can create shared spaces for deep learning, collaborative exploration, and joint development of circular solutions (Dwivedi et al., 2022; Radianti et al., 2020). However, extant literature has not yet adequately captured these processes or operationalized them in a sustainability context. This gap sets the stage for introducing the new construct “immersive knowledge co-creation” (IKCC), which captures the interactive and experiential value (i.e., experience-based qualities of interaction) of immersive platforms. This construct encompasses the collaborative development of ideas, solutions, and innovations within immersive digital environments.

Open eco-innovation capabilityWhile immersive platforms such as the metaverse offer promising environments for collaborative knowledge development, their effectiveness in driving circular innovation is not uniform across organizations. The ability to translate immersive interactions into meaningful sustainability outcomes depends heavily on an organization's readiness to embrace digital change and engage in open, cross-boundary innovation. Previous studies have emphasized that successful digital transformation, particularly for sustainability, requires not only technological infrastructure but also a culture of openness, strategic flexibility, and the willingness to collaborate with external stakeholders (Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014; Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, 2009). In the context of the CE, firms that lack these enabling conditions may struggle to leverage immersive technologies for co-creative and systemic innovation. This limitation is particularly salient in environments that demand both internal digital capability and external collaboration to address complex, interdependent challenges (Bogers et al., 2020).

To address this issue, scholars have drawn upon dynamic capabilities theory, which highlights the importance of an organization’s ability to reconfigure internal competencies and adapt to external environments (Teece, 2007). From this theoretical lens, there is growing recognition of a specific organizational capability that enables the integration of digital sustainability innovation with open innovation practices. This leads to the introduction of the construct “open eco-innovation capability” (OEIC), which reflects a firm’s capacity to simultaneously adopt eco-digital technologies and engage in collaborative innovation with external partners (Jesus & Jugend, 2023; Köhler et al., 2022).

Literature synthesisTo consolidate the insights from the above discussion, Table 1 presents a synthesis of key literature related to CE, metaverse, IKCC, and OEIC. The table outlines each concept's key contributions, identified gaps, and relevance to the present study.

Literature synthesis.

| Concept | Key Contributions in Literature | Identified Gaps/Limitations | Relevance to Current Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular economy(Bocken & Ritala, 2022; Brown et al., 2019; Camilleri, 2019; De Jesus & Mendonça, 2018; Eisenreich et al., 2021; Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Jaeger & Upadhyay, 2020; Kirchherr et al., 2017; Köhler et al., 2022; Lopes et al., 2017) | - Promotes resource efficiency, waste reduction, and sustainable production.- Emphasizes strategies such as eco-design, reverse logistics, and closed-loop systems. | - Limited empirical focus on how CE is operationalized in diverse organizations.- Lack of process-level understanding of stakeholder collaboration and implementation dynamics. | Highlights the need to explore interactive mechanisms that enable CE implementation within firms. |

| Metaverse in CE Context(Köhler et al., 2022; Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, 2009; Lyu & Fridenfalk, 2023; Papamichael et al., 2023; Piccarozzi et al., 2024) | - Offers immersive tools (e.g., digital twins, simulations) to visualize and design circular systems.- Supports remote, virtual collaboration. | - Mostly technocentric and conceptual.- Overlooks behavioral, collaborative, and contextual factors.- Lacks insight into human-centered interaction in virtual CE innovation. | Identifies the need to explore how immersive platforms contribute to collaboration and knowledge creation in the CE. |

| Immersive knowledge co-creation(Dwivedi et al., 2022; Grant, 1996; Lundvall, 1992; Nonaka, 2009; Radianti et al., 2020) | - Based on knowledge-based view and interactive learning theory.- Immersive environments foster shared learning and problem-solving. | - Understudied in sustainability and CE contexts.- Unclear how immersive collaboration translates to circular outcomes. | Experiential, collaborative learning and solution-building in the CE through the metaverse. |

| Open eco-innovation capability(Bogers et al., 2020; Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014; Jesus & Jugend, 2023; Köhler et al., 2022; Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, 2009; Teece, 2007) | - Based on dynamic capabilities theory.- Reflects firms’ ability to adopt eco-digital innovations and engage in open knowledge flows. | - Organizational readiness for immersive and collaborative innovation is often neglected in CE studies.- Integration with metaverse-based strategies is missing. | May shape how effectively organizations engage in immersive co-creation and scale circular innovation practices. |

While metaverse tools comprise a powerful technological infrastructure to support sustainability transitions, their effectiveness in achieving organizational outcomes depends mainly on the interactive processes they enable (Dwivedi et al., 2022). Simply adopting immersive technologies does not guarantee meaningful transformation; rather, what matters is how these tools are used to engage stakeholders, promote collaboration, and facilitate shared understanding (Radianti et al., 2020). In the context of the CE, which inherently requires systemic thinking and multi-actor alignment, traditional communication modes often fall short in enabling participatory, experiential engagement (Brown et al., 2019). Thus, there is a growing need to understand what type of collaborative mechanisms can translate the potential of metaverse tools into actionable sustainability practices.

IKCC addresses this need. It refers to the processes of shared learning, collaborative design, and joint problem-solving facilitated by immersive digital environments. This construct is grounded in the KBV and interactive learning theory, both of which emphasize that innovation and transformation arise from dynamic, experience-driven knowledge exchange (Grant, 1996; Lundvall, 1992). IKCC allows stakeholders to co-develop sustainable solutions, test scenarios in virtual settings, and align perspectives around circular strategies. Therefore, it is expected that the influence of metaverse adoption on CE implementation is channeled through this immersive, collaborative knowledge development process.

H1: Metaverse adoption has a positive effect on CE Implementation.

H2: Metaverse adoption has a positive effect on IKCC.

H3: IKCC has a positive effect on CE Implementation.

H4: The relationship between metaverse adoption and CE Implementation is mediated by IKCC.

The relationship between metaverse adoption and IKCC may not be uniform across organizations. Variations in internal readiness, digital maturity, and openness to external collaboration can significantly influence how effectively firms engage with immersive tools (Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014; Lichtenthaler, 2016). OEIC is introduced in this study as a dynamic organizational capability that reflects a firm’s preparedness to adopt eco-digital technologies and its willingness to co-innovate with external partners. Grounded in the dynamic capabilities theory, OEIC captures the strategic, cultural, and infrastructural orientation required to adapt to fast-evolving digital environments while aligning with environmental sustainability goals (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Teece, 2007).

Organizations high in OEIC are more likely to invest in the resources, processes, and collaborative structures needed to fully leverage metaverse-enabled collaboration (Bogers et al., 2020; Jesus & Jugend, 2023). Such firms can better integrate external knowledge, involve diverse stakeholders in immersive engagements, and convert shared virtual interactions into actionable learning. In contrast, organizations low in OEIC may lack the absorptive capacity or collaborative flexibility to translate digital tools into high-quality knowledge co-creation. Consequently, OEIC is expected to strengthen the effect of metaverse adoption on IKCC. This forms a pathway in which OEIC enables firms to utilize immersive technologies more effectively, generating knowledge that ultimately drives circular outcomes.

H5: OEIC positively moderates the relationship between metaverse adoption and IKCC, such that the relationship is stronger when OEIC is high.

Conceptual frameworkThe conceptual framework illustrated in Fig. 1 integrates key constructs and relationships from the preceding literature review and derived hypotheses. It proposes that metaverse adoption influences CE implementation both directly and indirectly through the mediating role of IKCC. Furthermore, the framework introduces OEIC as a moderating variable that shapes the strength of the relationship between metaverse adoption and IKCC.

Research methodologyResearch designIn this study, we employed a quantitative, cross-sectional research design to empirically test the proposed conceptual framework and its associated hypotheses. Given the study’s focus on the relationships among digital technology adoption, collaborative processes, organizational capability, and sustainability outcomes, a survey-based approach was employed to gather standardized data from a broad sample of firms. The conceptual model, which includes mediation and moderation effects, suggests variance-based structural equation modeling (SEM) using partial least squares (PLS-SEM) (Hair et al., 2019). This approach enables the analysis of both direct and indirect effects within the proposed framework.

Geographical context and samplingThe empirical context of this study is the advanced manufacturing sector in Germany, which encompasses industries such as automotive, industrial equipment, electronics, and smart factories. Germany was selected due to its leadership in sustainability policy, digital manufacturing innovation, and active engagement with CE principles under frameworks such as the European Green Deal (BMUV, 2022; European Commission, 2020). These industries are increasingly integrating technologies such as digital twins and immersive platforms, making them well-suited for investigating the influence of metaverse adoption on the CE implementation (BMWK, 2021; Müller et al., 2018). Previous research has shown that context-specific factors moderate the impact of innovative supply chain technologies on innovation, collaboration and performance (Wang & Zhang, 2025), so the decision to focus on a clearly defined sector in a particular geographical region is an attempt to control extraneous variables that could confound the relationships in our model.

A purposive sampling strategy was applied to identify firms actively engaged in sustainability initiatives and/or digital transformation efforts. Participants were selected from managerial and strategic roles, including sustainability officers, innovation managers, IT heads, and operations directors. A screening question ensured the inclusion of only those firms with at least some exposure to immersive or collaborative digital tools. The target sample size was set to exceed 200 valid responses, following statistical guidelines for structural models involving multiple latent constructs (Hair et al., 2019).

Data collection procedureData were collected through a structured online questionnaire, which was developed using validated measurement scales from existing literature. Before the full-scale rollout, the questionnaire underwent pretesting with a small group of sustainability and digital innovation experts to ensure item clarity and contextual relevance. Following this, a pilot study involving 30 professionals from the targeted industries was conducted to assess the reliability and consistency of the scales. Based on their feedback, minor wording adjustments were made. The final instrument demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding 0.70 for all constructs.

The questionnaire was distributed via professional networks, LinkedIn, and industry associations to promote diversity in terms of firm size, technological maturity, and digital adoption levels. A total of 890 questionnaires were distributed, of which 280 were returned, resulting in a response rate of approximately 31.5 %. Data collection was conducted between March 10 and April 28, 2025. Ethical research protocols were strictly followed, including obtaining informed consent, assuring participants of full anonymity, maintaining data confidentiality, and allowing respondents to withdraw at any time. The pretesting, pilot validation, and ethical considerations ensure that the study can be replicated in similar industrial contexts.

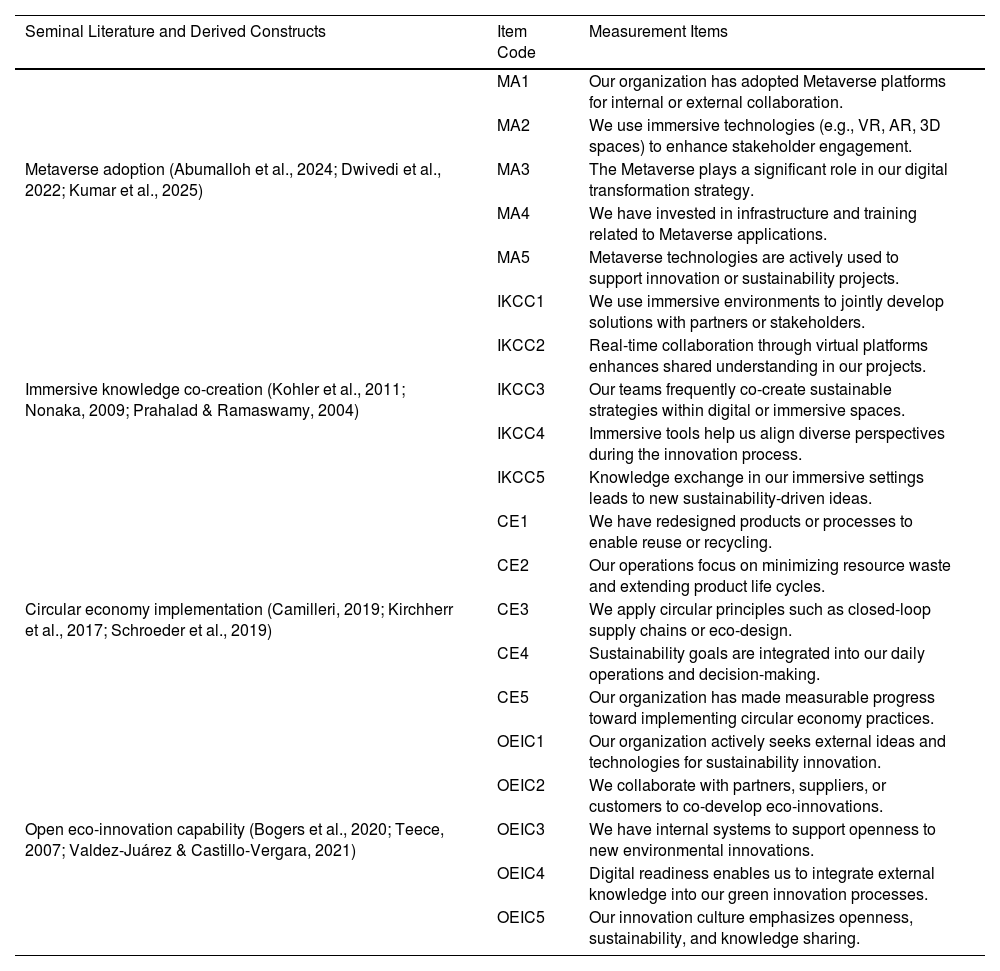

Construct measurementEach construct in the model was measured using multi-item Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The measurement items were developed in a structured and theory-based process based on a content analysis of relevant papers. We followed the principles of the COAR-SE framework from Rossiter (2002), which emphasizes construct clarity through the explicit definition of the objects together with their attributes, by first identifying the constructs of interest (as shown in Fig. 1). Following a content analysis of the respective papers, we derived representative items to reflect their essential content. Rather than relying solely on statistical one-dimensionality, the items were selected to ensure conceptual distinctiveness and complete coverage of the construct domain, with the goal of developing measurement scales that provide full domain coverage while simultaneously being parsimonious. To ensure content validity, we avoided repetitive phrasing across items and varied the structure and tone of the questions where appropriate. Feedback from three other researchers, who were also domain experts, further supported the face validity of the final measurement instrument. During the process, redundant and ambiguous items were removed.

Metaverse adoption items were derived from seminal papers discussing the implementation and use of the metaverse in the industry (Abumalloh et al., 2024; Dwivedi et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2025). IKCC was measured using items based on co-creation and collaborative innovation literature, aligned with the KBV (Kohler et al., 2011; Nonaka, 2009; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004). CE Implementation items were drawn from established CE frameworks focusing on design innovation, material circularity, and process transformation (Camilleri, 2019; Kirchherr et al., 2017; Schroeder et al., 2019). OEIC items were derived from prior studies on open innovation and dynamic capabilities, with a focus on sustainability orientation (Bogers et al., 2020; Teece, 2007; Valdez-Juárez & Castillo-Vergara, 2021). As discussed in the following sections, we assessed reliability and convergent validity by conducting Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) along with reliability tests, including Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability (CR). The complete list of items used to measure each construct is provided in the appendix.

Demographic profile of respondentsDemographic data were collected from all participants to provide a contextual understanding of the sample. Data were collected on industry sector, firm size, managerial role, years of experience, familiarity with metaverse technologies, and involvement in CE initiatives. These variables offer valuable insights into the organizational environment and respondent profiles relevant to metaverse adoption and CE practices. A total of 280 responses were received. After screening for completeness and relevance, 220 valid responses were retained for analysis. All participants held managerial or strategic positions within their organizations, ensuring their ability to provide informed perspectives on the adoption of immersive technologies and sustainability practices. Roles included sustainability managers, innovation and digital transformation leads, IT decision-makers, and operations directors.

As shown in Table 2, the majority of respondents came from automotive industries, followed closely by the electronics and industrial machinery industries, reflecting the specialization of Germany’s advanced manufacturing domain. In terms of firm size, a balanced distribution was observed across small (<50 employees), medium-sized (50–249), and large firms (250 and above), consistent with the structural profile of Germany’s manufacturing sector. Most participants held decision-making roles, such as sustainability/CSR managers and digital transformation leads, ensuring relevant insights into the constructs under study. A significant portion of the respondents reported more than five years of experience, suggesting depth in their organizational understanding. Regarding familiarity with the metaverse, most participants indicated moderate to high exposure, while a similarly high proportion were actively involved in CE initiatives, reflecting the sample’s alignment with the study’s thematic focus. These attributes confirmed the appropriateness of the sample for evaluating relationships among digital adoption, knowledge co-creation, organizational capability, and sustainability outcomes.

Demographic characteristics.

This section presents the results of the statistical analyses, beginning with the assessment of the measurement model to ensure reliability and validity, followed by the evaluation of the structural model and hypothesis testing using PLS-SEM in Smart PLS 4.0. The mediation and moderation effects were tested using a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples.

Common method bias assessmentSince data were collected using a single survey of individual respondents, there was a potential risk of common method bias (CMB). To test for this, both procedural and statistical remedies were applied. Procedurally, the questionnaire ensured anonymity and separated independent from dependent variables. Statistically, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The results showed that the first unrotated factor accounted for only 32.4 % of the total variance, well below the 50 % threshold, suggesting that CMB is unlikely to be a significant concern. Additionally, the full collinearity variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all constructs were below 3.3, which further supports the absence of substantial common method bias.

Measurement model assessmentTo evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement model, the indicators were tested for internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. As shown in Table 3, all constructs achieved acceptable reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.85 to 0.91 and composite reliability (CR) values between 0.88 and 0.93, all exceeding the recommended 0.70 threshold. The average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs ranged from 0.69 to 0.78, indicating satisfactory convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was examined using the Fornell-Larcker criterion. As shown in Table 4, the square root of each construct’s AVE (diagonal elements) was higher than its correlations with other constructs (off-diagonal elements), confirming that each construct was empirically distinct from the others.

Discriminant validity – fornell-larcker criterion.

Note: Diagonal values (in bold) represent the square root of AVE; off-diagonal values are inter-construct correlations.

Following confirmation of the measurement model, the structural model was assessed to evaluate the proposed direct, mediating, and moderating relationships. Multicollinearity was examined using VIF, and all values were below the threshold of 5, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern.

As shown in Table 5, the direct path from metaverse adoption to CE Implementation was positive and statistically significant (β = 0.18, t = 2.21, p < 0.001), thus supporting H1. This result suggests that greater adoption of metaverse technologies is associated with higher levels of CE Implementation. The path from metaverse adoption to IKCC was also significant (β = 0.22, t = 2.88, p < 0.001), providing support for H2. This indicates that immersive technologies contribute meaningfully to collaborative knowledge development processes within organizations. In addition, IKCC demonstrated a significant positive effect on CE Implementation (β = 0.25, t = 3.65, p < 0.001), confirming H3. This finding highlights the central role of co-created knowledge in translating immersive digital engagement into sustainable outcomes. To assess mediation, the indirect effect of metaverse adoption on CE Implementation through IKCC was examined. The result was statistically significant (β = 0.53, t = 6.45, p < 0.01), confirming H4 and indicating that IKCC partially mediates the relationship between metaverse use and CE Implementation.

For moderation, the interaction term between metaverse adoption and OEIC on IKCC was also significant (β = 0.31, t = 4.02, p < 0.01), thus supporting H5. This suggests that the effect of the metaverse on knowledge co-creation is strengthened in organizations with higher levels of eco-innovation capability.

Additional model diagnosticsWe performed additional diagnostics to assess the predictive capability and model fit beyond standard PLS-SEM outputs. As shown in Table 6, the Q² values for endogenous constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.30, indicating strong predictive relevance. The f² effect sizes were moderate to large, suggesting that the relationships among constructs explained a substantial portion of variance. Furthermore, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value was 0.071, which is below the accepted threshold of 0.08, confirming a good model fit.

Additional model diagnostics.

Note: Q² values > 0.30 indicate strong predictive relevance. SRMR < 0.08 indicates a good model fit.

The findings of this study offer valuable insights into how organizations can leverage digital technologies and open innovation capabilities to accelerate the transition from linear to circular economic models.

The mediation analysis shows that IKCC serves as the essential process through which metaverse platforms drive CE outcomes. While the metaverse has been discussed in CE research, most studies have focused on its technical features, such as digital twins or simulations, with limited attention to the collaborative dynamics that convert those tools into meaningful outcomes (Abumalloh et al., 2024; Dwivedi et al., 2022). Meanwhile, immersive technologies and co-creation processes have been shown to be effective in healthcare (Mantovani et al., 2003), education (Radianti et al., 2020), and service innovation (Pinho et al., 2014), improving experiential learning, user engagement, and stakeholder alignment (Nah et al., 2025). Despite this, their use in sustainability and CE transformation remains underexplored. This study addresses that gap by positioning immersive co-creation as the central mediating mechanism which explains how virtual collaboration, shared learning, and real-time problem-solving contribute to achieving circularity. This contribution is grounded in the KBV (Grant, 1996) and interactive learning theory (Lundvall, 1992), which together explain how digital tools facilitate innovation through the creation of knowledge-rich, experiential interactions.

The moderation analysis further strengthens these insights by revealing that OEIC enhances the translation of metaverse-based engagement into effective knowledge co-creation. While prior studies in digital eco-innovation (Bogers et al., 2020; Jesus & Jugend, 2023; Lichtenthaler, 2016; Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, 2009) have emphasized the importance of organizational culture, openness to partnerships, and digital infrastructure as key enablers of sustainability, these elements have primarily been examined in non-digital contexts. This study contributes to the current literature by demonstrating that even when immersive technologies are available, their effectiveness depends on the organization's internal capability to activate, integrate, and apply them within collaborative innovation ecosystems. By testing this relationship as a moderation effect, the study introduces a new layer of understanding. It highlights organizational capability as not just a support factor but as a strategic condition for unlocking the full value of immersive tools.

The findings suggest that, to fully support CE practices, immersive technologies need to be paired with an internal culture that fosters openness, eco-innovation, and digital transformation (Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014; Teece, 2007). According to Dhayal et al. (2025), immersive technologies such as the metaverse and digital twins can contribute to sustainability and circular economy goals only when embedded within a human-centric, eco-innovative, and organizationally supportive framework aligned with the Industry 5.0 paradigm. Rejeb et al. (2025) further highlight that the integration of these technologies within socially inclusive and digitally advanced industrial systems improves human-machine collaboration and empowers stakeholders to co-create sustainable value through circular and resilient production models.

By identifying the role of IKCC and OEIC in CE transformations, this study addresses several key gaps identified in the literature. Metaverse-based platforms enhance this dynamic by enabling real-time simulations, predictive analytics, and cross-functional collaboration, which collectively support transparency, operational efficiency, and innovation in circular supply chains (Butt et al., 2025). Second, the current study addresses the lack of collaboration by emphasizing IKCC as a mechanism that enables stakeholder alignment, shared learning, and joint problem-solving in virtual environments. Recent research indicates that when immersive technologies are underpinned by strong absorptive capacity and digital readiness, they have the potential to foster user co-creation and open innovation by enabling real-time collaboration and knowledge integration across organizational boundaries (Mubarak et al., 2024).

Third, this study addresses limited organizational readiness by highlighting OEIC as the capability that empowers firms to leverage digital tools within open innovation ecosystems. Together, IKCC and OEIC provide a process-driven and capability-based explanation for how immersive technologies can move beyond pilot-stage applications and contribute to scalable, organization-wide CE implementations. This contribution is theoretically grounded in dynamic capabilities theory, which asserts that organizations must continually reconfigure their internal and external competencies in response to changing environments (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Teece, 2007). In this study, reconfiguration occurs through the integration of immersive technology, collaborative knowledge creation, and innovation-oriented organizational culture to drive circular transition.

These findings extend the theoretical reach of innovation and sustainability literature into the immersive digital domain. By combining metaverse adoption, IKCC, and OEIC, the study offers a novel framework that directly addresses the fragmented implementation of CE strategies and the underutilization of immersive platforms in sustainability-oriented collaboration. It presents a distinctive contribution to CE research by introducing a process-driven, capability-anchored pathway for translating digital innovation into systemic and scalable CE implementation.

Theoretical implicationsThis study offers several important theoretical contributions to the literature on CE, open innovation, and digital transformation. First, it extends the KBV and interactive learning theory by introducing IKCC as a process-based mechanism through which immersive technologies promote shared learning, collaborative knowledge development, and interactive stakeholder engagement. These learning dynamics play a crucial role in enabling more effective implementation of circular economy practices within organizations. While prior research has highlighted knowledge sharing and collaboration as enablers of innovation, this study operationalizes these dynamics within a fully immersive context, adding depth to how shared learning can be digitally facilitated in CE transitions. Second, the study advances dynamic capabilities theory by empirically demonstrating that OEIC enables organizations to reconfigure their internal capacities and external relationships to better exploit immersive technologies for circular objectives. The integration of openness, digital readiness, and environmental orientation within this capability construct offers a novel conceptualization relevant for sustainability-focused digital innovation. Finally, by validating a proposed model, the research contributes to emerging scholarship that calls for multi-level, process-oriented models to explain how digital tools interact with organizational context to create systemic change. This framework connects technology adoption, knowledge transformation, and capability development into one coherent model, offering a foundation for future theoretical refinement.

Practical implicationsThis study provides several actionable insights for managers, policymakers, and digital transformation leaders aiming to promote CE strategies. First, it highlights that a successful metaverse adoption needs to be paired with processes encouraging active stakeholder collaboration and shared knowledge generation. Managers should invest not only in digital infrastructure but also in cultivating immersive, participatory engagement practices. Priority should be given to those Metaverse features that enable multi-user interaction in real time and the creation of persistent virtual spaces for co-design. Second, the findings underscore the need for organizations to develop or strengthen their OEIC, which includes openness to external partnerships, eco-innovation orientation, and digital maturity. Firms high in OEIC are better positioned to turn immersive collaboration into successful CE implementations. For policymakers, our study suggests that support for CE initiatives should go beyond funding technology acquisition and include capacity-building programs that enhance organizational readiness for digital-eco integration.

Conclusion, limitations and future researchThis study was motivated by the ongoing struggle many organizations face in effectively implementing CE principles, despite growing awareness and policy support. Existing research highlights barriers such as technological inertia, lack of collaboration, and organizational unreadiness. While immersive digital platforms such as the metaverse are emerging as promising tools, their application in CE remains underexplored, particularly regarding the processes and capabilities required to unlock their full potential. This study addresses that gap by proposing and empirically validating a model that links metaverse adoption to CE implementation through IKCC and OEIC. Using survey data from 220 respondents in Germany’s advanced manufacturing sector, the study employed PLS-SEM to test direct, mediating, and moderating effects. The findings revealed that IKCC is a key mediating process that enables firms to implement principles of the CE through the use of digital platforms, and that OEIC significantly strengthens this effect. These results suggest that technology alone is insufficient to achieve CE practices without the collaborative processes and organizational capabilities that support them. Practically, the findings guide firms seeking to scale CE through immersive tools by emphasizing the need to develop open innovation cultures and collaborative infrastructures. Theoretically, the model offers a new lens for understanding how digital ecosystems can support sustainability transitions. For policymakers, the research underscores the importance of supporting not just technological investment, but also organizational capacity-building for eco-innovation and digital collaboration.

While this study offers important contributions, several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the data were collected exclusively from the advanced manufacturing sector in Germany, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other industries or geographical contexts. Future research could validate and extend the model in different sectors such as retail, construction, or agriculture, and across diverse cultural or regulatory settings. Second, we employed a cross-sectional study design using newly developed measurement items, and further replication studies are needed to validate the identified relationships, as well as the properties of the newly developed scales used to measure the constructs. Future studies can further refine our model and include additional facets, such as the circularity status of a company, which may, in turn, affect perceptions of the metaverse. They also need to include a thorough discussion of adoption challenges and barriers such as implementation costs, complexity, internal resistance, and cybersecurity concerns. Finally, this study focused specifically on the metaverse as an immersive technology platform, excluding other cores such as digital simulations or mixed-reality spaces. Future research should investigate whether the observed relationships also hold true across these broader immersive ecosystems.

From a methodological viewpoint, future research could consider applying additional robustness checks to explore non-linear relationships and incorporate control variables such as firm age, R&D intensity, or prior digital transformation experience. These factors may help uncover the nuanced effects of metaverse adoption on circular economy outcomes across different levels of organizational maturity.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAman Ullah: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Horst Treiblmaier: Writing – original draft. Sana: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Abderahman Rejeb: Writing – original draft.

None

| Seminal Literature and Derived Constructs | Item Code | Measurement Items |

|---|---|---|

| Metaverse adoption (Abumalloh et al., 2024; Dwivedi et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2025) | MA1 | Our organization has adopted Metaverse platforms for internal or external collaboration. |

| MA2 | We use immersive technologies (e.g., VR, AR, 3D spaces) to enhance stakeholder engagement. | |

| MA3 | The Metaverse plays a significant role in our digital transformation strategy. | |

| MA4 | We have invested in infrastructure and training related to Metaverse applications. | |

| MA5 | Metaverse technologies are actively used to support innovation or sustainability projects. | |

| Immersive knowledge co-creation (Kohler et al., 2011; Nonaka, 2009; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004) | IKCC1 | We use immersive environments to jointly develop solutions with partners or stakeholders. |

| IKCC2 | Real-time collaboration through virtual platforms enhances shared understanding in our projects. | |

| IKCC3 | Our teams frequently co-create sustainable strategies within digital or immersive spaces. | |

| IKCC4 | Immersive tools help us align diverse perspectives during the innovation process. | |

| IKCC5 | Knowledge exchange in our immersive settings leads to new sustainability-driven ideas. | |

| Circular economy implementation (Camilleri, 2019; Kirchherr et al., 2017; Schroeder et al., 2019) | CE1 | We have redesigned products or processes to enable reuse or recycling. |

| CE2 | Our operations focus on minimizing resource waste and extending product life cycles. | |

| CE3 | We apply circular principles such as closed-loop supply chains or eco-design. | |

| CE4 | Sustainability goals are integrated into our daily operations and decision-making. | |

| CE5 | Our organization has made measurable progress toward implementing circular economy practices. | |

| Open eco-innovation capability (Bogers et al., 2020; Teece, 2007; Valdez-Juárez & Castillo-Vergara, 2021) | OEIC1 | Our organization actively seeks external ideas and technologies for sustainability innovation. |

| OEIC2 | We collaborate with partners, suppliers, or customers to co-develop eco-innovations. | |

| OEIC3 | We have internal systems to support openness to new environmental innovations. | |

| OEIC4 | Digital readiness enables us to integrate external knowledge into our green innovation processes. | |

| OEIC5 | Our innovation culture emphasizes openness, sustainability, and knowledge sharing. |