Digital innovation ecosystems (DIEs) are increasingly recognized as critical to regional green technological innovation (GTI), supporting ecological protection and sustainable development. This study uses panel qualitative comparative analysis (Panel-QCA) on data from 31 Chinese provinces (2013–2022) to explore how DIEs affect GTI through configurational effects and dynamic pathways. Results suggest two primary pathways to a high-level GTI: "Comprehensive Synergy among Innovation Actors" and "Collaborative Drive within Innovation Environments." The analysis shows that limited innovation in higher education institutions hampers high-level GTI, with external factors occasionally disrupting configurational stability. Theoretically, this study integrates the DIEs and dynamic QCA frameworks to clarify complex multi-factor interactions. Practically, it offers policy insights for boosting DIE-driven GTI across varied regional contexts.

The convergence of digital economic transformation and climate-driven decarbonization has established Green Technological Innovation (GTI) as a central pillar of sustainable development. While national policies and corporate strategies have been extensively studied, the regional dimension—where digital ecosystems interact with local industries and governance—remains underexplored (Shen et al., 2021). China’s provincial disparities offer a valuable context for this research: per the Guangdong Provincial Bureau of Statistics, in 2022 the digital economy accounted for 32 % of Guangdong’s GDP, while Hebei steel industry exhibited a digitalization rate below 15% (Yi et al., 2024). This diversity makes these regions an ideal setting to examine how DIEs shape GTI pathways across diverse institutional and technological contexts.

Regional analysis offers unique insights into GTI dynamics. Unlike national studies, which often generalize, provincial perspectives reveal how policies interact with regional resources (Gramkow & Anger-Kraavi, 2017; Oduro et al., 2022). For instance, blockchain-enabled supply chains in the Yangtze River Delta reduced energy intensity in battery recycling by 47% (Fan et al., 2023), while IoT-powered precision agriculture tripled water-efficient irrigation in the Loess Plateau. Such cases highlight regional governments as both architects of digital infrastructure (e.g., China’s "East Data, West Computing") and adaptive regulators, emphasizing that local factors such as university-industry collaboration and STEM literacy are pivotal to sustainable transitions.

This study centers on DIEs—networked systems integrating enterprises, universities, governments, and end-users through data flows and institutional coordination mechanisms (Autio & Thomas, 2022). Drawing on innovation ecosystem theory, DIEs facilitate non-linear value creation through three synergistic channels: (1) AI-driven environmental monitoring for real-time sustainability optimization, (2) predictive analytics to identify latent markets for green technologies, and (3) threshold effects in academic R&D investments spurring green patent growth. Empirical studies suggest that regions with proactive public engagement in scientific advancements exhibit greater corporate responsiveness to eco-innovation policy incentives (Zhao et al., 2022), underscoring the co-evolution of digital infrastructure and socio-cultural dynamics.

Despite growing interest, how DIEs drive regional GTI remains poorly understood (Wang et al., 2022). Prior research has two major flaws. First, at the theoretical level, studies often adopt a reductionist approach, using symmetric methods such as regression to isolate the "net effect" of factors like R&D investment or digital policy (e.g., Du et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022). While useful, this approach misaligns with the systemic nature of ecosystems, overlooking their synergistic, non-linear interplay among elements, and the principle of equifinality—where diverse factor combinations can produce the same outcome (Rihoux & Ragin, 2009; Fiss, 2011). Second, methodologically, while Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is well-suited to studying configurational phenomena, its application in this domain has been largely static. Cross-sectional analyses obscure the temporal dynamics of ecosystems, leaving unclear how causal configurations form, stabilize, or erode over time (Garcia-Castro & Ariño, 2016; Linyu et al., 2024; Rahman et al., 2025). This gap creates a significant policy challenge, particularly in a diverse nation like China, where uniform strategies often ignore regional variations in digital maturity and institutional capacity—resulting in inefficient and inequitable outcomes.

This study addresses these gaps by employing panel qualitative comparative analysis (Panel-QCA), which integrates configurational logic with longitudinal data. Using a decade of observations (2013–2022) from 31 Chinese provinces, we pose the following research questions: (i) what configurations of digital ecosystem elements drive high levels of GTI?, and (ii) how do these configurations evolve and maintain stability over time?

This study offers three main contributions. First, theoretically, it advances beyond a simplistic "list of ingredients" by developing and testing a dynamic configurational model of GTI that captures the interplay between innovation actors (enterprises, universities, users) and their enabling environments (policy, culture, data). Second, methodologically, it is among the first to apply Panel-QCA in this field to identify causal pathways and analyze their temporal stability and path dependence, offering a dynamic perspective on ecosystem evolution. Third, practically, by unravelling context-specific pathways, it challenges the effectiveness of uniform policies and provide a tailored, evidence-based guidance for regional leaders in China and beyond.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the preexisting literature and develops a theoretical framework for this study. Section 3 details the Panel-QCA methodology and data. Section 4 presents and discusses the empirical results. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper by discussing the study's implications, limitations, and avenues for future research.

Literature review and theoretical frameworkGTI: progress and disparitiesGTI is vital for sustainable growth and carbon neutrality, especially in emerging economies such as China. Regional disparities in GTI efficiency are evident in differences in patent activity, product commercialization, and waste management (Duan et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2023). Underlying these disparities are systemic issues such as fragmented policy implementation, limited cross-sectoral collaboration, and uneven public engagement (Takalo & Tooranloo, 2021). While environmental regulations (e.g., emissions standards, green subsidies) and market competition are established drivers of GTI (Du et al., 2021), the nonlinear dynamics of multi-stakeholder interactions within innovation ecosystems remain insufficiently understood.

Traditional studies often adopt a reductionist lens, focusing on the isolated impact of variables such as government policies or corporate R&D investments. However, GTI is inherently an interactive and co-evolutionary process, requiring active engagement among enterprises, universities, governments, and civil society (Wang et al., 2024). For example, universities provide foundational research and knowledge spillovers, while enterprises drive commercialization through market-oriented adaptation (Holroyd, 2020). Despite this interdependence, existing frameworks fail to adequately explain how these actors collectively configure pathways for green innovation amidst diverse resource and institutional constraints.

Innovation ecosystems and digital transformationInnovation ecosystem theory offers a comprehensive framework for understanding GTI as a complex system. Rooted in collaborative value creation, it unites diverse stakeholders—governments, firms, academia, and users—to drive GTI (Wang et al., 2021; Liu & Kim, 2024). This reframes GTI as a dynamic interplay of resource allocation, knowledge exchange, and institutional alignment, rather than a linear input-output process.

The digital revolution has transformed innovation systems into Digital Innovation Ecosystems (DIEs), which leverage modular platforms, big data analytics, and adaptive governance to reshape innovation trajectories (Hein et al., 2020). Digital platforms enable real-time collaboration between SMEs and research institutions, while AI-driven tools optimize resource efficiency in green product development (Luo et al., 2023). However, how DIEs foster GTI through configurational synergies remains empirically underexplored, especially in developing economies. Most studies rely on static, cross-sectional analyses, overlooking the temporal dynamics and path dependence essential to ecosystem evolution (Zeng et al., 2024).

Despite this interdependence, existing frameworks often fail to explain how these actors collectively configure pathways for green innovation amidst diverse resource and institutional constraints. To address this gap, this study develops an integrative theoretical framework based on the digital innovation ecosystem perspective, proposing a configurational model for understanding regional GTI.

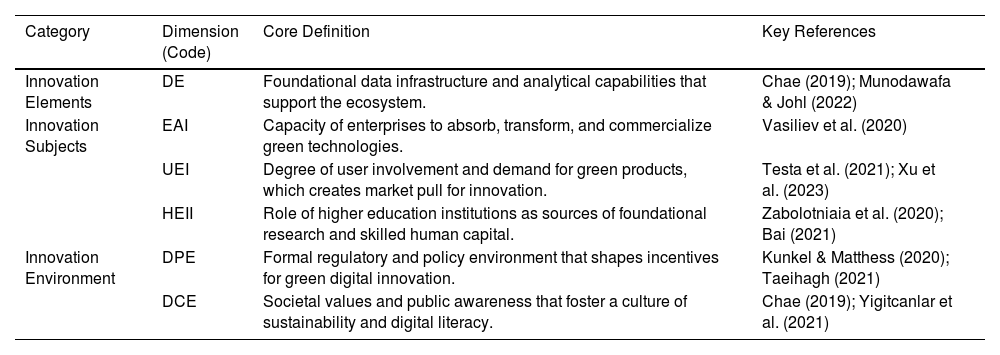

Theoretical framework: a digital innovation ecosystem perspectiveDrawing on the DIE theory (Munodawafa & Johl, 2022; Filiou et al., 2023), this study constructs an integrative framework to examine how regional GTI emerges from the dynamic interplay of three key dimensions, as depicted in Fig. 1. Grounded in the "Actors-Environment" logic central to ecosystem research (Autio & Thomas, 2022), the framework comprises three interrelated components— Innovation Elements, Innovation Subjects, and the Innovation Environment—which collectively shape GTI outcomes.

Innovation Elements (DE) represent the foundational data infrastructure that supports the ecosystem.

Innovation Subjects include Enterprises (EAI), Users (UEI), and Higher Education Institutions (HEII), which act as the primary drivers of innovation and commercialization, thereby extending the "Triple Helix" model into a digital context.

Innovation Environment comprises the Digital Policy Environment (DPE) and the Digital Cultural Environment (DCE), which collectively frame and constrain actor activities.

This triadic structure enables an analysis of GTI not merely as a sum of individual factors, but as the outcome of complex, co-evolutionary interactions across these dimensions. The subsections below elaborate on each component, with Table 1 providing a detailed summary.

Summary of DIE dimensions and core definitions.

| Category | Dimension (Code) | Core Definition | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Elements | DE | Foundational data infrastructure and analytical capabilities that support the ecosystem. | Chae (2019); Munodawafa & Johl (2022) |

| Innovation Subjects | EAI | Capacity of enterprises to absorb, transform, and commercialize green technologies. | Vasiliev et al. (2020) |

| UEI | Degree of user involvement and demand for green products, which creates market pull for innovation. | Testa et al. (2021); Xu et al. (2023) | |

| HEII | Role of higher education institutions as sources of foundational research and skilled human capital. | Zabolotniaia et al. (2020); Bai (2021) | |

| Innovation Environment | DPE | Formal regulatory and policy environment that shapes incentives for green digital innovation. | Kunkel & Matthess (2020); Taeihagh (2021) |

| DCE | Societal values and public awareness that foster a culture of sustainability and digital literacy. | Chae (2019); Yigitcanlar et al. (2021) |

Data Elements (DE): As the backbone of the DIE, data analytics enable firms to decode environmental trends, optimize resources, and accelerate green R&D. Real-time IoT data on energy consumption informs iterative improvements in clean production technologies (Song et al., 2019). Advanced machine learning models further enhance predictive capabilities, enabling simulation of eco-efficiency scenarios and prioritization of low-carbon innovations (Munodawafa & Johl, 2022). Cloud-based platforms integrate heterogeneous datasets, fostering cross-industry collaboration in sustainability monitoring.

Enterprise Innovation (EAI): Enterprises are the primary actors translating academic breakthroughs into market-ready solutions. Collaborative platforms linking enterprises with universities enhance knowledge transfer, shortening the time-to-market for green technologies (Vasiliev et al., 2020). Open innovation ecosystems enable firms to co-develop patents with startups, leveraging agile methodologies to scale circular economy solutions. Corporate venture capital further bridges funding gaps for pilot projects, aligning R&D with regulatory standards.

User Engagement (UEI): Consumer demand for sustainability exerts a strong market pull, incentivizing eco-design. Digital channels (e.g., social media) amplify user feedback loops, enabling rapid product refinement (Xu et al., 2023). Gamified mobile apps encourage active consumer participation in carbon footprint tracking, fostering behavioral shifts toward green consumption (Testa et al., 2021). Crowdsourcing platforms further democratize innovation by empowering users to co-design modular products for repairability and reuse.

University Innovation (HEII): Universities are critical engines of innovation, providing foundational research and skilled talent. Metrics such as university R&D expenditures and digital resource investments reflect their capacity to support ecosystem-wide innovation (Zabolotniaia et al., 2020). Interdisciplinary labs accelerate technology commercialization, with spin-off companies translating academic patents into climate-neutral applications. University-led hackathons also cultivate entrepreneurial skills, aligning curricula with industry demands for green digital competencies (Bai, 2021).

Digital Policy Environment (DPE): Regulatory frameworks—such as digital tax incentives and green procurement—set the "rules of the game," shaping collaboration incentives (Kunkel & Matthess, 2020). Dynamic policy instruments like sandbox regimes allow blockchain-based carbon credit trading to be tested, balancing compliance with innovation agility (Taeihagh, 2021). Cross-border data governance agreements further harmonize standards, reducing barriers to transnational green tech diffusion.

Digital Cultural Environment (DCE): Societal values favoring sustainability and digital openness foster trust and cooperation, reducing innovation network transaction costs (Chae, 2019). Grassroots digital literacy campaigns empower communities to advocate for eco-transparency, pressuring firms to adopt ethical AI practices. Cultural narratives around "smart green cities" also galvanize public-private partnerships, embedding sustainability into urban digital twins (Yigitcanlar et al., 2021).

Configurational dynamicsThis framework proposes that GTI outcomes emerge from the synergy among these dimensions rather than the influence of isolated factors. Regions with strong DPE (policy support for digital R&D), high HEII (university-industry partnerships), and robust DE (data analytics infrastructure) are more likely to achieve breakthrough innovations. Conversely, a deficiency in a key components, such as weak UEI (consumer demand) or low DCE (public environmental awareness), can create bottlenecks, disrupting configurational stability and ultimately hindering high level of GTI performance. Using Panel-QCA, this study captures these dynamic interactions, addressing gaps in static, single-period analyses.

This integrative approach advances DIE theory in the following ways:

Reconceptualizing GTI as an emergent outcome of multi-stakeholder configurations. Unveiling the temporal dynamics of how digital policies, cultural shifts, and technological capabilities co-evolve. Providing actionable, context-specific insights for policymakers to tailor ecosystem strategies across heterogeneous regional contexts.

This framework provides the theoretical foundation to empirically test how DIEs enable or constrain GTI, thereby offering a conceptual roadmap for sustainable transitions in emerging economies.

In summary, our theoretical framework posits that a high level of GTI is not the result of isolated factors but rather an emergent outcome of the synergistic configurations of DIE dimensions. This configurational hypothesis cannot be adequately tested with conventional linear methods. Therefore, to empirically investigate these complex causal recipes and their dynamics, we employ Panel-Qualitative Comparative Analysis (Panel-QCA), a methodology detailed in the next section.

MethodologyResearch designQCA integrates qualitative and quantitative approaches by focusing on multi-factor configurations rather than isolated variables, making it ideal for analyzing complex causal phenomena (Ragin & Strand, 2008). Traditional QCA methods, such as fuzzy-set, crisp-set, multi-set, handle diverse variables (e.g., continuous, binary, categorical) effectively. However, they are inherently static, overlooking longitudinal variations and case heterogeneity. This can overgeneralize conclusions when configurational patterns shift over time. To overcome these limitations, this study applies Panel-QCA to assess the configurational impact of digital innovation ecosystems (DIEs) on green technological innovation (GTI).

This method was selected for its advantages over longitudinal alternatives like fixed-effects (FE) or random-effects (RE) panel regression models. While FE/RE models estimate the 'net effects' of individual variables over time (e.g., the impact of university R&D on GTI), this study centers on how GTI emerges from the concurrent interplay of multiple factors. Panel-QCA captures causal complexity, equifinality, and conjunctural causation over time—insights that regression models cannot provide (Linyu et al., 2024). Incorporating concepts such as pooled-consistency (POCONS), between-consistency (BECONS), and within-consistency (WICONS), enable Panel-QCA to capture temporal and individual effects in configurational analysis (Garcia-Castro & Ariño, 2016).

This study analyzes a balanced panel dataset of 310 province-year observations (31 Chinese provinces over the period 2013–2022). Data were primarily derived from provincial statistical yearbooks, the China Statistical Yearbook, and the China Environmental Statistical Yearbook. Green patent data were sourced from the publicly available records of the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) and consolidated using the green patent classification codes provided by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Missing values were addressed using standard interpolation and imputation methods.

Data collection and measurementOutcome variable: GTIFollowing established literature, we use the number of green patent applications as a proxy for regional GTI. This variable is operationalized as the total count of independently filed green invention and utility model patents per province in a given year. The data were sourced from the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA).

Condition variablesDrawing from our theoretical framework, we selected six antecedent conditions. As each condition is a multi-faceted construct, we operationalize it by creating a composite index from multiple secondary indicators. To ensure objectivity, we employed the entropy weight method to determine the contribution of each indicator, producing a single comprehensive score that serves as the proxy for each condition. The specific indicators used for each composite index are detailed below:

DE: Measured by regional mobile internet access traffic, the number of internet broadband access ports, the number of web pages, and the count of IPv4 addresses.

EAI: Measured by internal R&D expenditures of enterprises, the number of websites per 100 enterprises, and the proportion of enterprises engaged in e-commerce activities.

UEI: Measured by the number of mobile internet users, mobile phone penetration rate, and the share of online retail sales in the total retail sales of consumer goods.

HEII: Measured by internal R&D expenditures of universities and the proportion of library electronic resource acquisition costs in annual expenditures.

DPE: Measured by the share of science and technology expenditure in general public budget expenditure, the comprehensive index of digital government, and the number of government websites per 10,000 people.

DCE: Measured by the number of regional science museums and the number of e-reading terminals in public libraries.

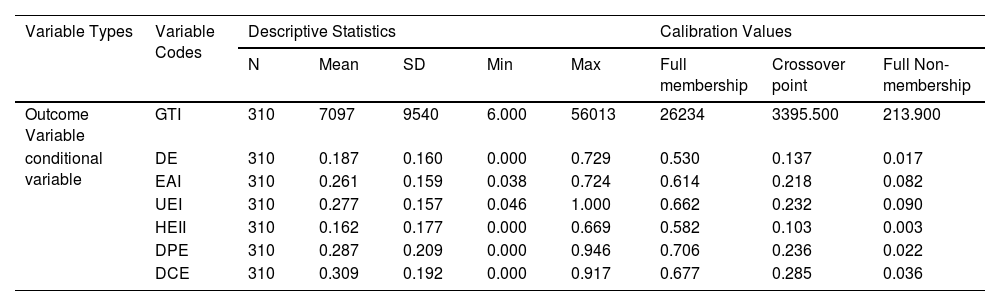

In QCA, both antecedent conditions and outcomes are conceptualized as sets. Converting raw data into set membership scores (ranging from 0 to 1) for each case is known as calibration. This study employs the direct calibration method , using theoretical and substantive criteria to define the thresholds for set membership. Following the approach of Yin and Wang (2024), the three crucial qualitative anchors—full membership (fully in the set), the crossover point (maximum ambiguity), and full non-membership (fully out of the set)—are set at the 95th, 50th, and 5th percentiles of the sample data for each variable, respectively. Additionally, following the recommendation of Du and Kim (2021), cases with a fuzzy membership score of exactly 0.5 were adjusted to 0.501 to avoid their exclusion during the truth table minimization. Table 2 reports descriptive statistics and the specific calibration anchors used for each variable.

Descriptive statistics and calibration values.

With the data and methodology established, we now present our empirical results. The analysis proceeds in two stages: first, we conduct a necessary condition analysis to identify factors that are indispensable for achieving high-level GTI; and second, we perform a sufficiency analysis to determine the configurations of DIE elements that consistently produce this outcome.

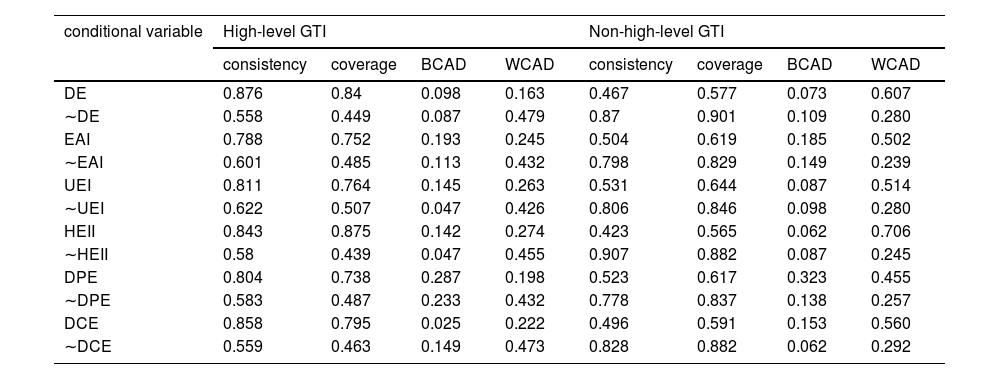

Necessary conditions analysisThe first stage tests whether any single antecedent condition is necessary for the outcome. Following Pappas et al. (2020), a condition is deemed necessary if its consistency score exceeds 0.9. As shown in Table 3, the consistency scores for all six conditions fall below this threshold, indicating that none is necessary for achieving high-level GTI. This result reinforces the central premise of this study: no single condition alone ensures high-level GTI. This absence of necessary conditions provides a strong justification for the subsequent sufficiency analysis, which examines how combinations of conditions produce the outcome.

Necessary conditions analysis.

Note: BCAD stands for between-consistency Adjustment Distance, WCAD stands for within-consistency Adjustment Distance.

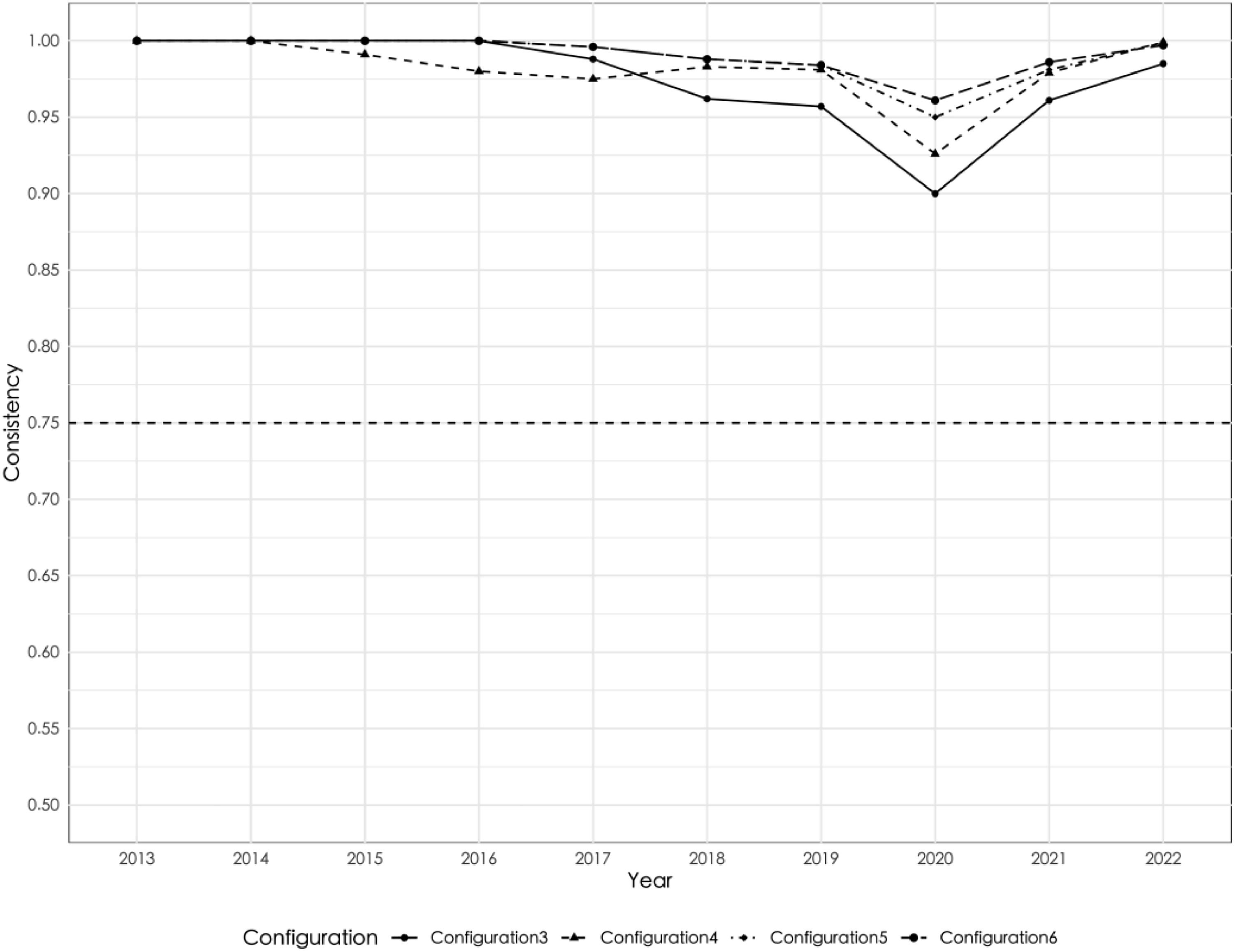

Under the Panel-QCA principles, a consistency adjustment distance (the difference between pooled and within-group consistency) above 0.1 signals significant temporal variation that warrants deeper investigation (Hossain et al., 2024). Our analysis reveals that four conditions—EAI, UEI, HEII, and DPE—exceed this threshold, indicating their unstable association with high-level GTI over time. As illustrated by the temporal plots in Fig. 2, the consistency scores for these conditions fluctuate significantly between 2013–2022. For instance, the consistency of UEI remained stable until 2018. reflecting changing impacts of user demand and participation on GTI, with its influence fluctuating over time. Similarly, the consistency of EAI declined after 2019, suggesting diminished returns from initial corporate investments in GTI amid intensifying competition. The consistency of DPE, while initially high, gradually declined after 2015, likely due to the diminishing marginal effects of early government policies.

In summary, the necessary condition analysis reveals that no single DIE element functions as a "single critical factor" for achieving high-level GTI. No single condition or its absence meets the 0.9 consistency threshold, provides compelling evidence against simplistic, single-factor explanations. This finding strongly supports the core premise that regional GTI emerges from the synergistic interplay of multiple interdependent elements. This result underscores the need to move beyond linear, variable-centric logic toward the holistic, configurational approach employed in the subsequent sufficiency analysis.

Configurational sufficiency analysisOur finding that no single DIE element constitutes a necessary condition for high-level GTI prompts an examination of how these elements combine into configurations sufficient for the outcome. Following QCA standards, we set a consistency threshold of 0.8, indicating that a configuration is a reliable subset of the outcome (Ragin & Strand, 2008; Fiss, 2011). To reduce contradictory configurations, we apply a Proportional Reduction in Inconsistency (PRI) threshold of 0.7, a conservative choice for exploratory research with theoretical ambiguities (Du & Kim, 2021). Given the large sample size (N=310), we used a case frequency threshold of 3 to ensure the resulting configurations reflect recurring patterns rather than idiosyncratic cases (Pappas et al., 2020). Consistent with QCA protocol, we report the intermediate solution as our primary finding and use the parsimonious solution to distinguish between core and peripheral conditions. Table 4 presents the results of the sufficiency analysis, detailing configurations leading to high-level GTI (Solutions S1-S2) and its absence (Solutions S3-S6).

A dynamic analysis of the solutions reveals that the between-group consistency adjustment distances for all configurations are below the 0.1 threshold, indicating overall temporal stability. However, for the configurations leading to the absence of high-level GTI, the within-group consistency adjustment distance exceeds 0.1, suggesting that case-specific dynamics play a significant role in these particular pathways.

Pathways to high-level GTIOur analysis identifies two distinct pathways to achieve high-level GTI:

Solution 1 (S1): Comprehensive Synergy among Innovation Actors.

This pathway reflects strong synergy among the three core innovation actors (EAI, UEI, and HEII), complemented by a supportive Digital Cultural Environment (DCE) and robust Data Elements (DE). In this configuration, user engagement (UEI) seems pivotal. The market pull created by green consumer demand serves as a feedback mechanism, stimulating corporate R&D investment (EAI) and reinforcing university-industry collaboration (HEII). DE act as a peripheral condition, enabling informed decision-making through real-time environmental monitoring. A supportive DCE fosters trust and pro-environmental values, enhancing corporate responsibility and proactive GTI engagement. This solution has the highest coverage, accounting for 187 province-year observations, and is empirically prominent in economically advanced regions such as Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Shanghai (see Fig. 3).

Solution 2 (S2): collaborative drive within innovation environmentsThis pathway emphasizes the critical role of innovation environments, which synergize with HEII and DE to drive GTI. DIE, supported by university R&D collaboration, provide a robust policy and social framework for high-level GTI. This pathway appears in 33 cases, primarily from Anhui, Hubei, and Fujian (Fig. 4).

Pathways leading to non-high-level GTIFrom the configurations in Table 4 for S3, S4, S5, and S6, the absence of DE, user participation in innovation, and university-based innovation, alongside limited digital policy support, leads to non-high-level GTI. Likewise, the lack of user participation and university-based innovation, combined with insufficient enterprise application innovation and a suboptimal DCE, results in non-high-level GTI even with moderate digital policy support. These findings further underscore the synergistic interplay among innovation elements, innovation actors, and the innovation environment.

In essence, our configurational analysis identifies two distinct, equifinal pathways to high-level GTI and four leading to its absence, underscoring that success can be achieved in multiple ways. Rather than a single universal model, regions can harness diverse strengths to advance green innovation. The two successful pathways—"Comprehensive Synergy among Innovation Actors" (S1) and "Collaborative Drive within Innovation Environments" (S2)—reflect actor- and environment-driven models, respectively. Conversely, low-GTI configurations consistently underscore the negative impact of weak university innovation and low user engagement.

Robustness checkTo assess the robustness of our findings, we adjusted the PRI threshold from 0.7 to 0.8. The results reveal that the configurations for both high-level and non-high-level GTI remain largely consistent, with only minor variations in the representative cases associated with each configuration. This consistency underscores the robustness of our results.

Between-group resultsFig. 5 illustrates consistency changes for the "Comprehensive Synergy among Innovation Actors" (S1) and "Collaborative Drive within Innovation Environments" (S2) configurations. Since 2015, both have maintained consistency levels above 0.75, demonstrating strong path dependence on digital innovation ecosystem conditions.

Fig. 6 highlights the changes in consistency levels for non-high-level GTI pathways, with one pathway fluctuating in 2020, likely due to COVID-19 restrictions on digital innovation actors such as users and universities. Nonetheless, the between-group adjustment distance remains below 0.1, indicating strong explanatory power for these pathways leading to non-high-level GTI.

Within-group resultsTable 3 shows that the within-group consistency adjustment distances for the two high-level GTI configurations are below 0.1, indicating high stability and reliability over time. Conversely, the four non-high-level GTI configurations have higher within-group consistency adjustment distances, highlighting significant instability in the digital innovation ecosystem conditions of the typically less-developed provinces following these pathways.

ConclusionsResearch conclusionsGrounded in DIE theory, this study develops a framework to explore how six dimensions—DE, EAI, UEI, HEII, DPE, and DCE—synergistically influence regional green technological innovation (GTI). Using Panel-QCA configuration path analysis, we conducted an in-depth analysis of panel data from Chinese provinces between 2013 and 2022, yielding the following key conclusions:

First, unlike single-factor analysis frameworks prevalent in prior research, this study adopts a multi-factor configurational approach within the DIEs, revealing GTI’s driving mechanisms through multi-actor and multi-element interactions. The findings highlight that DIE elements align synergistically to create an innovation ecosystem that collectively fosters GTI.

Second, compared to previous studies, this study addresses the limitations of static QCA and traditional regression analysis in exploring complex causal mechanisms. The Panel-QCA method uncovers dynamic temporal pathways through which multiple condition combinations influence GTI. Two primary pathways for GTI are identified, demonstrating the diversity and flexibility of the DIEs in driving GTI.

Third, the DIEs exhibit minimal variation in pathway selection for high-level GTI but significant heterogeneity in pathway selection for non-high-level GTI. University-based innovation emerges as a critical factor influencing GTI.

Theoretical implicationsThis study enhances understanding the role of DIE in fostering GTI by shifting from linear causality to dynamic configurational complexity. Our contributions stand in contrast to the limitations of traditional research approaches.

First, we challenge the prevailing "net effects" logic and adopt a configurational perspective on equifinality in green innovation. Unlike regression-based studies that isolate individual variables’ effects (Li et al., 2022), assuming a single causal model, we identify two distinct pathways to high-level GTI: S1 ("Comprehensive Synergy among Innovation Actors") and S2 ("Collaborative Drive within innovation Environments"). These provide robust evidence for equifinality, showing that regions can achieve similar outcomes through different "recipes." This advances innovation ecosystem theory by moving beyond universal best practices toward context-specific pathways to success.

Second, we refine the theory of causal asymmetry. Linear models often assume that factors explaining success are simply the inverse of those explaining failure. Our findings reveal a more nuanced picture: while strong enterprise innovation (EAI) is central to the "actor-driven" pathway (S1), its absence (∼EAI) does not consistently define pathways to non-high-level GTI. Instead, weak university innovation (∼HEII) and low user engagement (∼UEI) emerge as more critical barriers. This causal asymmetry highlights that the drivers of success and the obstacles to it are not mirror images.

Third, we reframe ecosystem elements as contingent conditions rather than independent drivers. Traditional studies might deem a strong Digital Policy Environment (DPE) universally critical for GTI (Zhao & Qian, 2024; Geng et al., 2023). Our configurational approach reveals its contingent role: DPE is pivotal in the "environment-driven" pathway (S2) but absent in S1. This suggests that an element’s importance depends on the broader configuration, shifting the theoretical focus from "Is factor X important?" to "Under what conditions does factor X matter most?" This contingency perspective aligns innovation ecosystem theory with complexity science, adding much-needed theoretical depth.

Practical implicationsThis study offers practical guidance for policymakers aiming to advance GTI through integrated ecosystem configurations rather than standalone policies. We outline two key strategies, supported by examples:

First, cultivate actor-centric collaboration, particularly in developed regions. Our findings highlight a potent pathway (“Comprehensive Synergy among Innovation Actors,” S1), driven by close partnerships among enterprises, universities, and users, prominent in Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Shanghai. To achieve similar success, policymakers should move beyond subsidies to fund digital collaboration platforms linking corporate R&D with university research and user feedback. For instance, Guangdong’s “Industrial Internet” enables real-time data sharing and collaborative projects between firms like Midea and local universities, accelerating energy-efficient appliance development using consumer insights. They should also promote user-driven green innovation through public campaigns and gamified apps to encourage sustainable consumption and involve users in designing green products. Shanghai’s carbon-credit system, rewarding citizens for using public transport or recycling, exemplifies how to generate demand for sustainable solutions.

Second, enhance the institutional environment to spur innovation, especially in developing regions. The “Collaborative Drive within Innovation Environments” pathway (S2), observed in Anhui and Hubei, shows that a robust policy and data framework can propel GTI even with limited enterprise or user involvement. To capitalize on this, policymakers should integrate digital policies with university R&D investment and prioritize strong DPE and HEII. For instance, Anhui’s investment in the University of Science and Technology of China for AI and data science, paired with the “Anhui Brain” data platform, which creates a solid foundation for firm-level innovation. They should also reduce risks for green innovation through green procurement mandates and digital tax incentives (DPE) to create a stable market for green technologies. Hubei’s support for the electric vehicle supply chain through government contracts and infrastructure demonstrates how such policies encourage firms to invest in green R&D.

Limitations and future researchThis study provides fresh insights into the dynamic configurations underpinning regional GTI, yet its limitations highlight promising directions for future research.

First, our analysis is rooted in the Chinese context, where specific institutional frameworks, industrial policies, and developmental stages shape the identified pathways. While regional diversity within China enhances the robustness of our findings, their applicability to other contexts—such as market-driven economies in Europe, state-led systems elsewhere in Asia, or the varied economies of Latin America—remains uncertain. Future research could involve multi-country Panel-QCA studies to identify universal and context-specific factors driving digitally-enabled GTI.

Second, while our QCA approach effectively identifies configurations sufficient for GTI, it is less suited to revealing the nuanced, micro-level causal mechanisms within these configurations. For instance, how does a supportive digital culture (DCE) translate into tangible enterprise innovation (EAI)? What collaborative routines or trust-building processes drive the synergy in Pathway S1? To address these “how” and “why” questions, future research must adopt a mixed-methods approach, combining macro-level quantitative insights with in-depth qualitative case studies. Comparing a province exemplifying Pathway S1 (e.g., Jiangsu) with one representing Pathway S2 (e.g., Anhui) could yield valuable insights into actor-level strategies, institutional challenges, and policy dynamics obscured in large-N data.

Third, while our configurational approach offers valuable insights, it has limitations. A methodological limitation is the potential for endogeneity and simultaneity among antecedent conditions. For example, strong enterprise innovation (EAI) and high-level university innovation (HEII) may reinforce each other, or successful green innovation might prompt more supportive government policies (DPE). While QCA’s set-theoretic framework is less prone to endogeneity biases than regression-based causal estimates, it cannot fully resolve these reciprocal dynamics. From an ecosystem perspective, such co-evolution is intrinsic to the phenomenon. Future research could address this by combining panel VAR with Panel-QCA in a mixed-methods framework. Finally, while our framework is comprehensive, it is not exhaustive. Future research could enhance the model by incorporating additional factors, such as green finance, international knowledge spillovers, or inter-regional competition and collaboration to develop a fuller understanding of regional GTI.

CRediT authorship contribution statementQian Liu: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yuanji Zhang: Conceptualization. Xiaoqing Sun: Writing – review & editing, Data curation.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.