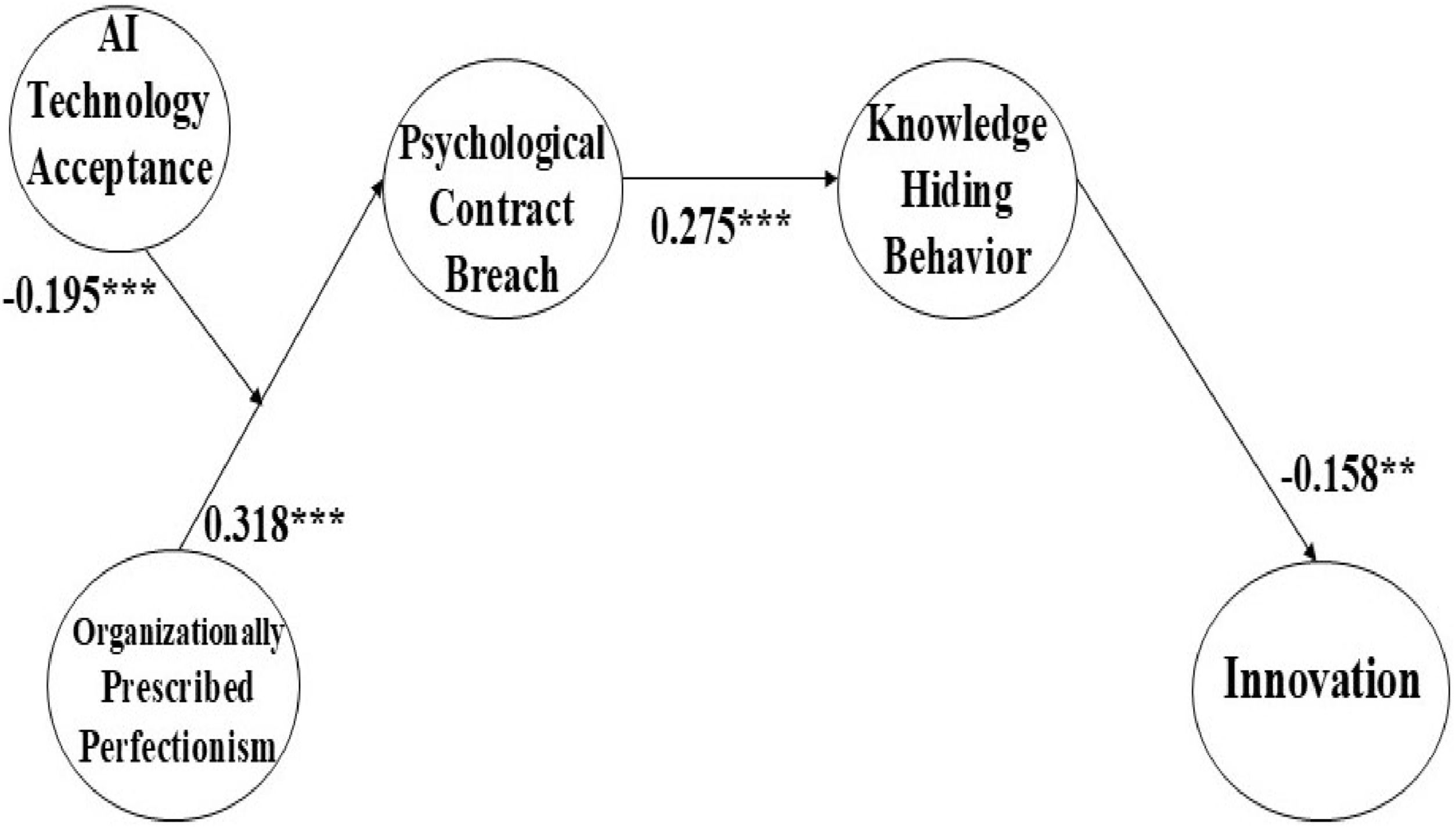

This study investigates how organizationally prescribed perfectionism (OPP) influences organizational innovation through the sequential mediating roles of psychological contract breach (PCB) and knowledge-hiding behavior (KHB), with artificial intelligence technology acceptance (AITA) demonstrating a moderating impact. Adopting a four-wave, time-lagged research design, data were gathered from 849 employed adults in South Korea, yielding 363 usable responses. The measurement model was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis, which demonstrated the distinctiveness of the core constructs. Structural equation modeling assessed the hypothesized relationships and revealed that OPP had no direct effect on innovation; rather, its impact was mediated by PCB, which occurs when employees perceive the unyielding demands of an organization as violating mutual obligations, and subsequently by KHB, which refers to individuals withholding work-related information. This chain of unfavorable perceptions and behaviors ultimately diminishes organization-level innovation capacity. Furthermore, AITA functioned as a crucial buffer in the link between OPP and PCB, signifying that employees who were more receptive to AI tools were less likely to interpret perfectionistic standards as unfair. This study’s findings enhance the current theoretical discourse by highlighting a multi-level explanatory process that elucidates how externally imposed performance pressure erodes innovation potential. The results also demonstrate technological acceptance’s pivotal role in mitigating such challenges.

Organizationally prescribed perfectionism (OPP) originates from the broader notion of socially prescribed perfectionism, whereby employees perceive that external entities (i.e., the organization) impose demanding performance standards upon them (Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Flett et al., 2022). In an increasingly competitive global marketplace, organizations frequently set exceptionally high benchmarks to distinguish themselves and maintain a competitive edge (Kim et al., 2024; Kim & Lee, 2025; Ocampo et al., 2020). Although perfectionist expectations may motivate employees to strive for quality work, they can also foster high-pressure environments and reduce flexibility. This dynamic is particularly salient in modern enterprises characterized by tight deadlines and performance metrics that reward minimal errors. Thus, a deeper examination of OPP is necessary to determine its impacts on both employee experiences and overall organizational performance.

Considering the rapid pace of change and the increasing complexities of global business environments, determining OPP’s influence on employees’ attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors is vital to maintaining market competitiveness. Employees working under rigid standards may feel required to expend substantial energy to avoid even minor mistakes, potentially impeding collaboration and innovative risk-taking (Kim et al., 2024; Mohr et al., 2022). Understanding these ramifications is critical as the cumulative effect of employees’ day-to-day choices—including whether to share knowledge, voice novel ideas, or commit to continuous learning—can profoundly impact organizational effectiveness. Therefore, further inquiry into how OPP functions in demanding workplaces is essential for developing a nuanced perspective of its broader organizational outcomes.

Despite the growing interest in perfectionism-related issues, OPP’s influence on organizational innovation has received relatively limited scholarly attention. Innovation remains a cornerstone of sustainable competitiveness and long-term success, especially in environments marked by frequent technological and market disruptions (Argote et al., 2011; Chesbrough, 2019; Teece, 2010; Raisch et al., 2018; Cai et al., 2020). However, organizational environments characterized by excessive performance pressure and punitive responses to errors can diminish employees’ psychological safety and creativity, which is integral to developing novel products and processes (Edmondson, 1999; Baer & Frese, 2003). Thus, exploring the relationship between perfectionism and organizational innovation is critical, as innovation underpins strategic renewal and buffers against obsolescence in turbulent industries (Teece, 2007; O'Reilly III & Tushman, 2021; Helfat & Raubitschek, 2018).

This link between OPP and innovation warrants particular attention for several reasons. First, organizations experience an inherent paradox as they must maintain rigorous standards to ensure operational excellence while fostering the psychological safety necessary for innovative risk-taking (Edmondson & Lei, 2014; Sherf et al., 2021). This tension is particularly pronounced in knowledge-intensive industries, which require both precision and creative problem-solving. Second, as organizations increasingly invest in innovation-driven strategies to secure a competitive advantage (Anderson et al., 2014), understanding how perfectionist climates undermine these initiatives is pivotal for achieving strategic alignment. Third, the psychological mechanisms through which perfectionist expectations influence employees’ willingness to propose novel ideas remain underexplored, resulting in a significant gap in our comprehension of innovation inhibitors (Miron-Spektor et al., 2018). Finally, organizational cultures often emphasize excellence and flawless execution in response to market pressure (Groysberg et al., 2018). Therefore, examining how these perfectionist standards affect innovation capabilities offers crucial insights that are vital for sustainable organizational performance.

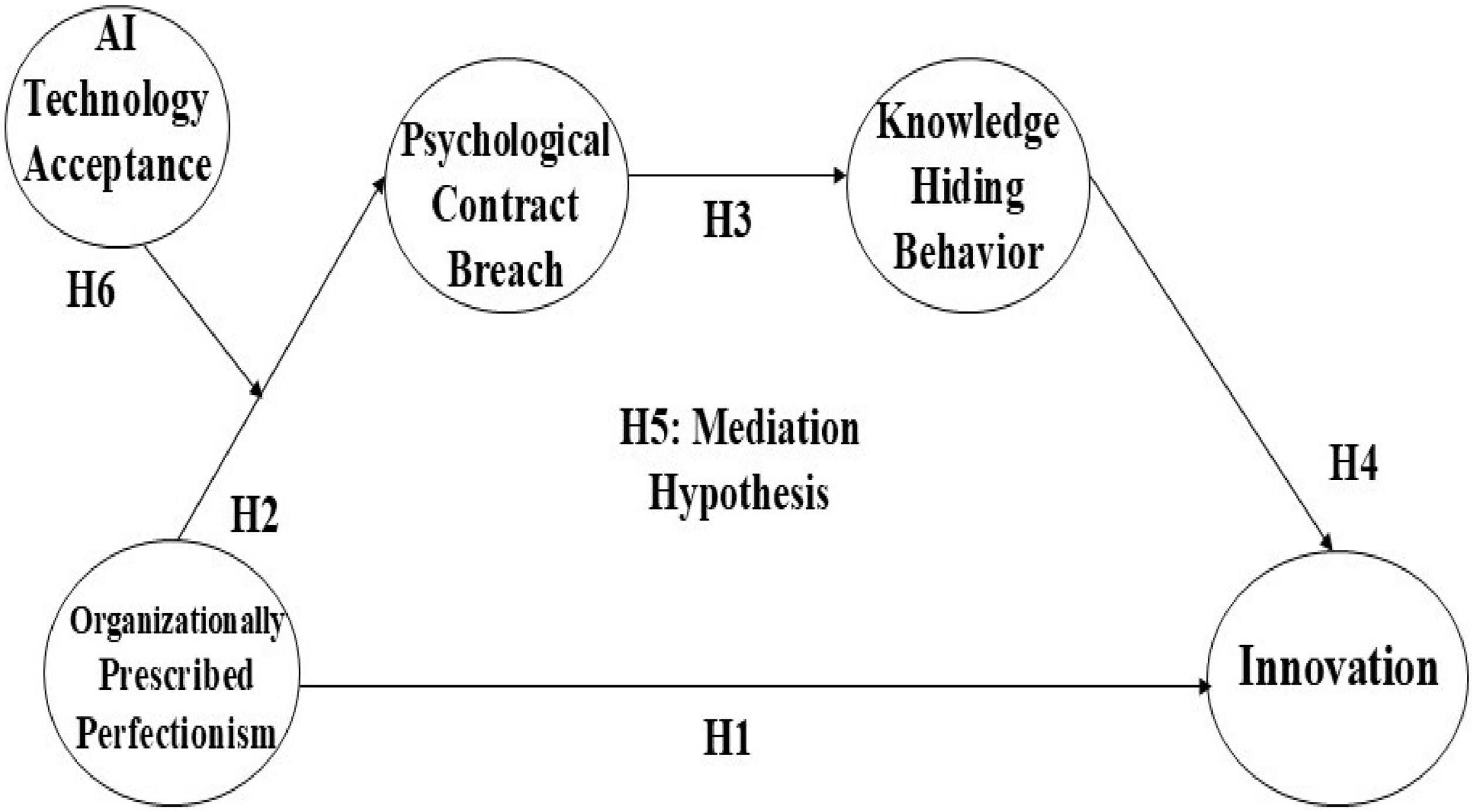

Furthermore, existing studies have often overlooked the underlying processes and contingent factors elucidating the link between OPP and organizational innovation. While it is important to acknowledge the direct relationship between these two variables, a more nuanced understanding is required. Thus, it is essential to analyze the mediating variables that clarify the processes involved, as well as the moderating variables that explain the conditions under which this relationship may be strengthened or weakened. It is also necessary to investigate the sequential mediating role of employee perceptions and behaviors, including psychological contract breach (PCB; Rousseau et al., 2018) and knowledge-hiding behaviors (KHB; Anand et al., 2022; Connelly et al., 2012), in the relationship between OPP and innovation. Examining these mediating variables can deepen the understanding of OPP’s influence on organizational innovation.

Another research gap concerns the relatively sparse evidence on moderating conditions, particularly those associated with artificial intelligence (AI). Despite the increasing prevalence of AI-driven technologies in contemporary work settings, researchers have yet to extensively explore how related variables, such as AI technology acceptance (AITA), can mitigate or amplify the adverse effects of perfectionist cultures (Dwivedi et al., 2021; Pan & Froese, 2023). Particularly, AI tools can help streamline tasks and support decision-making; thus, employees who embrace AI may be better equipped to navigate the stringent expectations of demanding environments. Conversely, low AI acceptance may exacerbate feelings of overload, thereby heightening perceptions of contract violation and impeding collaborative endeavors.

To address these gaps in the literature, this study draws on robust theoretical foundations that integrate insights from social exchange theory (SET) and the job demands-resources (JD-R) framework. In doing so, it demonstrates the relational dynamics and resource-based considerations underlying OPP and examines how PCB and KHB sequentially mediate the link between perfectionist norms and innovation. This study also highlights AITA’s potential buffering role, positing that employees who readily adopt AI-driven tools experience less strain and are less likely to perceive a contract breach, even in high-pressure environments. This integrated theoretical approach aims to clarify how perfectionism affects employee experiences and behaviors, ultimately influencing an organization’s innovative capacity.

This study makes four notable contributions. First, it enriches the related literature by introducing and examining OPP to highlight how externally imposed high standards shape employee experiences within competitive work contexts. Second, it advances the understanding of how OPP impairs key organizational outcomes by underscoring its negative implications regarding employee perceptions (i.e., PCB) and collaborative behaviors (i.e., KHB). Third, it offers a detailed account of how these perceptions and behaviors function as sequential mediators, illustrating the processes that connect OPP to reduced innovation. Finally, this study identifies AITA as a moderating mechanism, proposing that employees’ willingness to embrace AI-driven tools mitigates the negative effects of perfectionist demands by alleviating performance pressures and fostering a more resilient work environment.

Theory and hypothesesOrganizationally prescribed perfectionismNotably, OPP is regarded as a work-specific extension of socially prescribed perfectionism, wherein an organization (rather than a general entity) is perceived to impose exacting and typically unrelenting standards on employees. OPP demonstrates how individuals experience pressure not only from ambiguous or diffused sources but also from formal and informal organizational practices, cultural norms, and leadership expectations, which collectively signal a mandate for error-free performance (Kim et al., 2024; Kim & Lee, 2025). This heightened sense of obligation stems from the perception that the organization, as an authority structure, demands flawless outcomes, either explicitly or implicitly, compelling employees to pursue perfection in alignment with these prescribed standards.

The OPP construct is theoretically grounded in Hewitt and Flett’s (1991) Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS); specifically, the socially prescribed perfectionism dimension, which focuses on perfectionist standards perceived to be imposed by others. Unlike the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), which primarily assesses clinical characteristics, the MPS specifically measures perfectionism as a multidimensional construct based on self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism (Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Hewitt et al., 2003).

Socially prescribed perfectionism’s adaptation to organizational settings has emerged as a compelling research area over the past decade. Although the construct is relatively novel and necessitates further empirical evidence, Ocampo et al. (2020) conducted an initial validation by examining how externally imposed perfectionist standards function in the workplace context, noting OPP’s distinctiveness from general socially prescribed perfectionism, alongside its unique antecedents and outcomes. Subsequent empirical research by Kim et al. (2024) and Kim and Lee (2025) further established the construct’s discriminant validity utilizing confirmatory factor analyses, proposing that OPP is empirically distinct from related constructs, such as general workplace perfectionism, performance pressure, and unrealistic expectations. These studies demonstrated that the MPS’s six-item adaptation of socially prescribed perfectionism to organizational contexts exhibits satisfactory internal consistency (α ranging from 0.82 to 0.89) and predictive validity for diverse organizational outcomes (Hill & Curran, 2016; Ocampo et al., 2020).

Like socially prescribed perfectionism, OPP arises from external pressure sources and elicits a heightened fear of failing to attain the organization’s perceived benchmarks. Unlike self-oriented perfectionism, wherein individuals set rigorous goals, OPP entails the belief that one’s worth or acceptance in the workplace depends on satisfying rigid performance criteria, often leaving limited room for error or iterative learning (Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Hill & Curran, 2016). Consequently, individuals experiencing OPP report feelings of anxiety, self-doubt, and diminished psychological well-being as they operate under the assumption that any flaw or shortcoming jeopardizes their professional reputation (Ocampo et al., 2020; Ozbilir et al., 2015). Consistent with broader scholarship on perfectionism, this externally imposed mandate exacerbates harmful coping mechanisms and intensifies self-criticism, ultimately undermining sustainable performance and occupational health (Hill & Curran, 2016; Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Ocampo et al., 2020). Studies in organizational behavior contexts have reported that such externally driven perfectionist norms precipitate adverse outcomes, including burnout, elevated stress, and counterproductive work behaviors, particularly in high-demand settings (Flett et al., 2022; Kim & Lee, 2025; Mohr et al., 2022; Ocampo et al., 2020).

Organizationally prescribed perfectionism and innovationWe postulate that OPP decreases an organization’s innovation capacity. Organizational innovation is broadly regarded as the deliberate generation and application of novel ideas, processes, and outputs that enhance a firm’s performance, adaptability, and market competitiveness. It involves introducing novel products and services (generally termed as product innovation) and refining existing operational methods (generally termed as process innovation), thereby influencing how an organization maintains relevance and achieves a strategic edge (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001; Utterback & Abernathy, 1975).

The concept of organizational innovation has been refined by recent conceptualizations that emphasize its multidimensional and dynamic nature (Kahn, 2018; Goffin & Mitchell, 2016). Specifically, innovation is conceptualized as a complex organizational capability comprising the following interconnected components: (1) ideation capacity (the ability to generate novel and useful ideas), (2) implementation efficacy (the ability to transform ideas into tangible outputs), (3) value creation (the extent to which innovation generates measurable benefits for stakeholders), and (4) adaptability (the ability to continuously evolve innovation processes in response to changing environments) (Chae & Choi, 2019; Raisch et al., 2018). Moreover, contemporary frameworks have distinguished between incremental innovation (improvements to existing offerings), architectural innovation (novel reconfigurations of existing components), and radical innovation (fundamental departures from existing practices), each requiring distinct organizational conditions and processes (Lee & Trimi, 2021; Tidd, 2023). Innovation has increasingly been conceptualized as a socially embedded process rather than merely an outcome, which emerges from collaborative practices, knowledge networks, and organizational climates that facilitate experimentation and psychological safety (Cai et al., 2020; Randhawa et al., 2017).

Acknowledging innovation’s deep entanglement with several contemporary megatrends is crucial to further contextualize it in the modern era. First, digital transformation has profoundly reshaped innovation landscapes by leveraging various technologies, including big data analytics (Sivarajah et al., 2024), AI, and interconnected platforms. This process has fundamentally altered how organizations operate, create value, and interact with stakeholders (Hanelt et al., 2021; Plekhanov et al., 2023; Vial, 2021). Digital transformation not only drives the need for innovation ambidexterity, which involves balancing exploration and exploitation, but also fosters resilience (Li et al., 2025, forthcoming). Second, recognition of innovation in broader ecosystems is growing, comprising diverse, interdependent actors that collectively contribute to innovation generation and diffusion through collaboration and competition, including firms, customers, suppliers, research institutions, and policymakers (Adner, 2017; Baldwin et al., 2024). Effectively navigating these ecosystems necessitates the nuanced implementation and adoption of open innovation practices. Third, sustainability-oriented innovation has become a critical imperative; thus, firms are increasingly channeling innovative efforts to address pressing environmental and social challenges in alignment with sustainable development goals (Dzhunushalieva & Teuber, 2024; Urbinati et al., 2023). These initiatives include green technological innovation that impacts organizational and environmental performance (Opazo-Basáez et al., 2024) and innovations in sustainable operations processes such as recycling (Liu et al., 2025, forthcoming). Finally, AI’s rise has significantly transformed innovation management via tools such as natural language processing, which has enhanced creative capabilities and search processes (Gama & Magistretti, 2025, forthcoming; Just, 2024; Roberts & Candi, 2024). AI has also enabled the development of new products and services through its specific applications (Cooper, 2024; Mariani & Dwivedi, 2024).

As organizations navigate increasingly complex and rapidly evolving environments, their innovation capacity constitutes a critical dynamic capability, enabling a sustainable competitive advantage through continuous adaptation and renewal (Teece, 2020; Xiao, 2024). Innovation’s multidimensional capacity can establish a more comprehensive foundation for examining the influence of various organizational factors (e.g., perfectionism) on innovation processes and outcomes. This multifaceted process typically relies on an organization’s ability to synthesize knowledge from diverse internal and external sources, thus fostering a climate that actively encourages exploration and experimentation (Argote & Miron-Spektor, 2011). Substantial research has demonstrated innovation’s crucial role in achieving sustained growth and maintaining competitive positioning, particularly in dynamic contexts where market demands evolve rapidly (Jansen et al., 2006; Wright & McMahan, 1992).

Specifically, OPP reflects an organizational climate that imposes rigorous and frequently unforgiving standards on employees, compelling them to consistently attempt to maintain flawless performance. In such an organization, employees may feel obligated to adhere to exceedingly stringent standards, fearing criticism or other negative repercussions if they fall short of expectations (Kim et al., 2024; Ocampo et al., 2020). Although perfectionism may motivate high-quality work, it may also diminish employees’ willingness for creative risk-taking when imposed externally, ultimately impeding the emergence of novel products, processes, and solutions.

The JD-R framework and SET substantiate our argument; however, they have historically been examined independently. Nevertheless, we propose that these theoretical perspectives are complementary and mutually explain the relationship between OPP and reduced innovation (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Cropanzano et al., 2017), offering distinct yet interconnected explanations for why demands for perfectionism impair innovative capacity (Demerouti et al., 2001; Shore et al., 2006).

First, based on the JD-R framework (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007, 2017), unrelenting organizational expectations can gradually deplete individuals’ physical and mental resources (Demerouti et al., 2001; Crawford et al., 2010). Though not inherently detrimental, job demands become problematic when they drain resources faster than they can be replenished (Hobfoll, 2001; ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), leaving limited capacity to engage in creativity (Sacramento et al., 2013; Van Dijk et al., 2017). That is, employees under constant pressure to achieve error-free results may hesitate to take risks, such as experimenting with novel or untested methods. Constant vigilance against even minor errors can result in compliance and avoidance, reducing the resources necessary for engaging in creative problem-solving and exploratory thinking (Mohr et al., 2022). Over time, such preoccupation with error prevention can limit the flexibility required for generating novel ideas and adapting to challenges (Wright & McMahan, 1992; Xiao, 2024).

Mitigating this resource depletion process is imperative for enabling innovation, as creative thinking and risk-taking, which constitute core components of the innovation process, require substantial cognitive and emotional resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Demerouti et al., 2001). When perfectionist demands deplete these resources, employees’ capacity for exploratory behavior diminishes, directly impacting innovation’s cognitive foundations (Anderson et al., 2014). The relationship between resource depletion and reduced innovation becomes especially evident when considering that innovation necessitates cognitive flexibility and the willingness to experiment, qualities that are constrained when resources are diverted toward error prevention (Mohr et al., 2022; Ocampo et al., 2020).

Second, as underscored by SET, OPP can distort the relational dynamics crucial for collaborative innovation (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano et al., 2017). Notably, SET helps elucidate how perfectionism influences collaborative relationships. Homans (1961) posited that individuals engage in relationships with the expectation of achieving either a tangible or psychological ‘profit’ and tend to disengage from relationships when costs exceed benefits. Specifically, he stated: “people seek profitable relationships and will dislodge from those that are not profitable” (Homans, 1961, p. 80). Within organizational contexts, this principle helps explain why employees adjust their voluntary contributions according to perceived imbalances in exchange relationships.

Blau (1964) expanded upon this understanding by emphasizing that social exchange involves voluntary actions motivated by expected future returns; however, these returns remain largely unspecified: “Social exchange refers to voluntary actions of individuals that are motivated by the returns they are expected to bring and typically do in fact bring from others” with a “general expectation of some future return, although its exact nature is definitely not stipulated in advance” (Blau, 1964, p. 93). These uncertain future returns are highly relevant in innovation contexts, as contributions to collaborative processes typically yield unpredictable or delayed benefits.

When employees perceive that the organization’s uncompromising demands surpass the support or recognition they receive, they may conclude that the exchange relationship is skewed in the organization’s favor (Rousseau et al., 2018). This imbalance fundamentally violates the reciprocity principle that Blau (1964) identified as the foundation of sustainable exchange relationships. Emerson (1976) termed this perceived imbalance as ‘exchange ratios,’ which trigger a series of protective responses aimed at restoring equity, including the withdrawal of voluntary collaborative efforts that drive innovation.

Furthermore, SET directly complements the JD-R-based explanation by accounting for innovation’s relational dimension (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Shore et al., 2006). While the JD-R framework explains how perfectionism affects individuals’ internal resources, SET underscores how it disrupts the interpersonal exchanges necessary for collaborative innovation (Blau, 1964; Connelly et al., 2012). Innovation rarely occurs in isolation and often requires integrating diverse perspectives, expertise, and insights (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005; Jansen et al., 2006). When demands for perfectionism foster perceived imbalances in exchange relationships, the willingness to engage in knowledge-sharing and collaborative problem-solving diminishes (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Rousseau et al., 2018).

These dynamics directly undermine an organization’s ability to nurture innovation, which commonly involves continuously refining existing products or services and exploring potential novel directions (Danneels, 2002; Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001; Utterback & Abernathy, 1975). Effective innovation demands both exploitative capabilities (i.e., employees enhancing a firm’s core offerings) and exploratory efforts (i.e., employees experimenting with novel opportunities) (Jansen et al., 2006). Achieving this balance requires a culture that supports risk-taking, encourages knowledge exchange, and instills trust that pursuing new ideas will not be penalized (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005).

Integrating these theoretical perspectives elucidates how OPP creates a dual impediment to innovation. First, it depletes the cognitive resources necessary for creative thinking (the JD-R perspective) (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Demerouti et al., 2001). Second, it erodes the relational dynamics required for collaborative innovation (the SET perspective) (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano et al., 2017). Importantly, these mechanisms do not function in isolation but rather interact with and amplify each other (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Rousseau et al., 2018). As resource depletion reduces employees’ ability to maintain positive exchange relationships, the deterioration of these relationships further burdens employees’ cognitive and emotional resources, progressively undermining innovation capacity (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Cropanzano et al., 2017).

In a perfectionist climate imposed by an organization, employees’ priority shifts from embracing the iterative trial-and-error processes that drive breakthrough developments to eliminating missteps (Ocampo et al., 2020). Consequently, their inclination to challenge established routines and propose unconventional insights declines, thus eroding the firm’s innovation potential.

These theoretical mechanisms collectively explain why OPP is expected to negatively impact innovation across multiple levels (Kozlowski & Klein, 2000). At the individual level, depleted resources and perceived exchange imbalances reduce employees’ willingness to engage in exploratory thinking and knowledge sharing (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Cropanzano et al., 2017). At the team level, individual-level effects aggregate to foster collaborative barriers and diminish knowledge exchange, thereby impeding collective creativity (Jansen et al., 2006; Connelly et al., 2012). At the organizational level, team-level effects result in a culture that prioritizes error avoidance over creative exploration, systematically restricting innovation capacity (Jansen et al., 2006; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005; Ocampo et al., 2020).

In sum, the JD-R framework elucidates how externally mandated perfectionism burdens employees’ personal resources, and SET highlights why this burden is magnified when they perceive an imbalance in reciprocation. By conflating resource depletion with deteriorating relational norms, OPP diminishes an organization’s capacity for product and process innovation. Given these considerations, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 1 OPP decreases innovation.

We propose that OPP elevates PCB among employees. PCB refers to an employee’s perception that an organization has failed to fulfill its promised obligations within the mutual understanding commonly termed as a psychological contract (Rousseau, 1989; Coyle‐Shapiro & Kessler, 2000). Unlike formal contracts, which focus on explicit employment terms, a psychological contract encompasses nuanced and typically unspoken expectations between employees and employers. A breach occurs when employees believe that commitments have not been adequately fulfilled, such as career advancement opportunities, job security, and supportive work environments (Topa et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2007). Upon perceiving a violation, employees may exhibit adverse reactions, reducing their organizational commitment, trust in management, and job satisfaction, and increasing the likelihood of turnover and counterproductive behaviors (Conway & Briner, 2005; Coyle‐Shapiro et al., 2019; Kutaula et al., 2020). These reactions typically originate from the realization that the organization has failed to fulfill implicit promises and expectations, thereby undermining employees’ sense of reciprocity and fairness (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2000; Rousseau et al., 2018).

Perceived OPP may compel employees to invest disproportionate amounts of time and emotional energy in preventing minor missteps, leaving them with limited resources to fulfill other obligations. Over time, such pressures may result in the impression that the organization excessively burdens employees while neglecting to fulfill its responsibilities, thereby fostering the conditions for perceived PCB (Kim & Kim, 2024a; Kim & Lee, 2025).

This study draws on SET and psychological contract theory (PCT) to explain this relationship. SET and PCT are generally considered distinct frameworks; however, they share foundational conceptual roots and act in tandem to explain how OPP increases PCB (Robinson et al., 2000; Shore et al., 2006). Collectively, they offer complementary perspectives that strengthen our understanding of how demands for perfectionism trigger PCB. Integrating these theories offers a more comprehensive explanation of the relationship between OPP and PCB than either theory could provide individually (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Rousseau et al., 2018).

First, SET interprets this dynamic by highlighting how employees and employers engage in ongoing transactions revolving around trust, reciprocity, and perceived balance (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano et al., 2017). When employees believe that organizational rewards, whether in the form of support, recognition, or even emotional consideration, do not match their efforts to satisfy perfectionist requirements, they may perceive a violation of the fundamental principle of reciprocity (Cropanzano et al., 2017). Thus, the belief that the organization is making greater demands than it is willing to offset erodes trust in the exchange relationship’s fairness.

SET suggests that OPP precipitates an imbalance in the exchange relationship, which employees will likely detect (Coyle-Shapiro & Conway, 2004; Cropanzano et al., 2017). Demands for perfectionism not only increase employees’ expected contributions to the exchange (e.g., high effort, constant vigilance, and emotional labor) but also decrease their payoff (e.g., less autonomy, psychological safety, and tolerance for learning through mistakes) (Conway & Briner, 2005; Robinson et al., 2000). This dual effect of heightened contributions and diminished returns results in a perceived exchange imbalance, which links OPP to the feelings of inequity preceding PCB (Shore et al., 2006; Topa et al., 2022).

Second, PCB theory offers a complementary explanation for why OPP fosters perceptions of breach (Rousseau et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2007). Though unwritten, psychological contracts encompass mutual obligations that employees believe the organization has implicitly agreed to uphold, such as fair treatment, reasonable workloads, and access to necessary resources. In perfectionist work environments, employees frequently interpret stringent performance criteria as contradicting organizational assurances of equity and support. Consequently, they may perceive that the employer has failed to deliver on the implicit promises integral to their understanding of a fair employment relationship. Once employees perceive these unwritten contracts as violated, they are more likely to experience disillusionment and dissatisfaction, hallmark indicators of PCB.

Furthermore, PCT extends SET by underscoring how OPP contrasts the content of typical psychological contracts (Rousseau, 1989; Coyle‐Shapiro & Kessler, 2000). Most psychological contracts include implicit promises of reasonable expectations, supportive feedback, and fair evaluation; however, perfectionist climates generally undermine these elements (Conway & Briner, 2005; Kutaula et al., 2020). Recognizing that high demands fundamentally alter employees’ perceived ‘deal’ with their organization better elucidates the connection between OPP and PCB (Robinson et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2007). When organizations transition toward unattainable standards without explicitly acknowledging this change in expectations, employees interpret this shift as a unilateral modification of the psychological contract—a primary trigger of perceived breach (Morrison & Robinson, 1997; Rousseau et al., 2018).

Integrating SET and PCT offers a more robust theoretical foundation for understanding the OPP–PCB relationship (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Shore et al., 2006). While SET explains employees’ evaluation of exchange fairness and recognition of imbalances, PCT highlights how these imbalances violate implicit promises within the employment relationship (Conway & Briner, 2005; Robinson et al., 2000). Collectively, these theories illustrate how OPP fosters both a general sense of inequity (SET) and specific perceptions of violated implicit promises (PCT), thereby comprehensively explaining why perfectionist demands increase PCB (Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2019; Rousseau et al., 2018).

Integrating SET and PCT helps elucidate how OPP erodes the relational and perceptual foundations between employees and employers. While SET illuminates employees' reduced trust and perceived fairness due to their sense of disproportionate effort relative to organizational reciprocation, PCT highlights how they interpret these demands as evidence of the organization’s failure to uphold its implied commitments. Therefore, when perfectionist standards surpass employees’ considerations of sustainable and fair treatment, a perceived breach in trust is likely to emerge.

Given this rationale, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 OPP increases PCB.

We posit that elevated PCB substantially increases KHB. Notably, KHB refers to an employee’s intentional attempts to withhold or conceal requested work-related information from others (Connelly et al., 2012). This ‘hidden knowledge’ encompasses varied forms of work-relevant information, including specialized expertise, procedural know-how, contextual insights, problem-solving approaches, and lessons from prior experience that could benefit colleagues or the organization if shared. This concealment occurs despite the individual possessing the requested knowledge and recognizing its potential utility to the requester. KHB manifests in several distinct forms, such as playing dumb (i.e., feigning ignorance), evasive hiding (i.e., providing misleading or incomplete information), and rationalized hiding (i.e., offering justifications for not sharing, such as confidentiality concerns) (Connelly et al., 2012; Connelly & Zweig, 2015).

Recent research has reported KHB’s detrimental effects on individual and organizational outcomes. For instance, employees engaging in KHB can disrupt collaboration, reduce team performance, and diminish collective problem-solving (Arain et al., 2024; Siachou et al., 2021). Moreover, studies have suggested that KHB is reciprocally associated with negative interpersonal dynamics, as once an employee withholds knowledge, coworkers may respond similarly, resulting in a cycle of mutual concealment that undermines trust and cohesiveness (Connelly & Zweig, 2015; Siachou et al., 2021). At a broader level, organizations that tolerate or inadvertently encourage KHB may experience reduced innovation capacity and a weakened climate for open communication and learning (Connelly et al., 2012; Jeong et al., 2022).

PCB refers to an employee’s perception that the organization has failed to uphold its unwritten promises and implied obligations, which unsettles the perceived balance of reciprocity in the workplace (Rousseau et al., 2018). Notably, PCT’s application to innovation contexts presents unique challenges. Unlike routine tasks and performance-based roles, which are clearly stipulated in formal employment agreements, knowledge-sharing and innovation activities are complex, unpredictable, and challenging to codify in traditional contractual terms (Alge et al., 2003; O’Neill & Adya, 2007). As Zhou and George (2001) observe, the discretionary nature of creative work implies that organizations must largely depend on employees’ voluntary engagement rather than explicit contractual mechanisms to stimulate innovation.

This contractual ambiguity is particularly relevant in examining how PCB affects knowledge-sharing behaviors. Formal contracts tend to specify certain performance metrics and work deliverables, but generally cannot adequately capture the nuanced interpersonal dynamics that facilitate knowledge exchange and collaborative innovation (Mura et al., 2013). When employees perceive PCB, their withdrawal from voluntary knowledge sharing represents a response to perceived inequities in domains that formal contracts cannot effectively regulate (Lin, 2007; Conway & Briner, 2005).

When PCB occurs, employees frequently re-evaluate the fairness of ongoing exchanges and may feel they are contributing more to the organization than they receive in return. This perceived imbalance motivates them to adopt self-protective behaviors, including restricting the information or knowledge that they had previously shared openly (Cropanzano et al., 2017). That is, employees’ perception that the employer has not fulfilled its obligations may reduce their inclination to help, believing that the principle of mutual support has been violated.

The relationship between PCB and KHB can be better understood by examining how SET and PCT interact in explaining employees’ behavioral responses to perceived PCB (Morrison & Robinson, 1997; Cropanzano et al., 2017). While these theories are often applied separately, their integration provides a more comprehensive explanation of why employees experiencing PCB tend to engage in KHB (Conway & Briner, 2005; Zhao et al., 2007).

We draw on SET and PCT to explain this association. First, SET theoretically elucidates why perceived shortfalls in employer obligations may heighten KHB (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano et al., 2017). According to SET, employees are willing to engage in constructive behaviors when they anticipate reciprocation that fosters trust and balance. Nevertheless, if perceived breaches undermine this anticipated reciprocity, employees may respond negatively by withdrawing from collaborative efforts (Jeong et al., 2022). Specifically, KHB functions as a strategic approach to withholding valuable resources (i.e., information or expertise) that would typically be shared under conditions of trust and equitable exchange (Connelly et al., 2012). In doing so, employees express discontent and safeguard their sense of security in an environment they deem unreliable.

Based on SET, knowledge represents a valuable social currency in organizational exchanges (Cabrera & Cabrera, 2005; Wang & Noe, 2010). When employees perceive PCB, they strategically adjust their contributions to the exchange relationship (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Shore et al., 2006). KHB seems an appealing response to this adjustment as it enables employees to withhold a resource that is both valuable to the organization and largely under their personal control (Connelly et al., 2012; Serenko & Bontis, 2016). Unlike other overt withdrawal behaviors that may attract formal sanctions, KHB is challenging for supervisors to detect and address (Connelly & Zweig, 2015; Siachou et al., 2021).

Simultaneously, PCT underscores that a perceived PCB is not isolated; rather, it disrupts the broader mental framework whereby employees interpret their obligations to the employer (Rousseau et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2007). PCB can erode the mutual understanding that underpins cooperative behaviors. Consequently, employees regard KHB less as an unwarranted act of defiance and more as a rational means of restoration when their employer has failed to uphold foundational commitments (Siachou et al., 2021).

Further, PCT extends this understanding by explaining the cognitive and emotional processes that link breach perceptions to KHB (Morrison & Robinson, 1997; Rousseau et al., 2018). When employees experience PCB, they undergo a cognitive recalibration of the employment relationship as described by Dulac et al. (2008), shifting from a relational orientation rooted in mutual commitment to a more transactional one focused on minimizing personal costs. This cognitive transition directly impacts how employees categorize knowledge, from a communal resource intended for collective benefit to a personal asset to be protected and selectively exchanged (Anand et al., 2022; Serenko & Bontis, 2016). Additionally, PCB typically triggers emotional responses, such as feelings of violation and betrayal (Morrison & Robinson, 1997; Zhao et al., 2007), which stimulate KHB as a means of emotional self-protection and even retaliation (Connelly & Zweig, 2015; Wang & Noe, 2010).

Integrating SET and PCT offers a more robust explanation of the PCB–KHB relationship than either theory could provide independently (Conway & Briner, 2005; Cropanzano et al., 2017). Moreover, SET explains the exchange-based mechanism whereby employees determine that KHB represents a rational response to perceived imbalances, while PCT elucidates the cognitive and emotional processes that transform this response into KHB (Dulac et al., 2008; Rousseau et al., 2018). Collectively, these theories explain why employees who experience PCB engage in KHB as a primary response, rather than other forms of withdrawal (Anand et al., 2022; Connelly et al., 2012).

In sum, SET and PCT underscore how diminished trust and perceived reciprocity following a breach make employees more likely to safeguard knowledge rather than share it. Given these theoretical insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 PCB increases KHB.

We posit that decreased KHB substantially reduces innovation. Notably, KHB pertains to the deliberate act of withholding or concealing information from colleagues, despite possessing the relevant knowledge (Connelly et al., 2012; Connelly & Zweig, 2015). Unlike mere ignorance or a lack of competence, KHB involves an intentional effort to withhold vital resources and expertise, typically driven by motives such as mistrust, job insecurity, and competitive workplace dynamics (Arain et al., 2024; Siachou et al., 2021). Scholars have emphasized that this behavior assumes many forms, including playing dumb, evasive hiding, and outright rationalized hiding, each reflecting a distinct strategy that employees apply to avoid providing information (Connelly et al., 2012; Connelly & Zweig, 2015).

Recent research has demonstrated KHB’s detrimental effects on both individual and organizational outcomes. For instance, employees engaging in KHB frequently disrupt collaboration, reduce team performance, and diminish collective problem-solving (Arain et al., 2024; Siachou et al., 2021). Moreover, studies have indicated that KHB is reciprocally associated with negative interpersonal dynamics, as once an employee withholds knowledge, coworkers may respond similarly, resulting in a cycle of mutual concealment that undermines trust and cohesiveness (Connelly & Zweig, 2015; Siachou et al., 2021). At a broader level, organizations that tolerate or inadvertently encourage KHB may experience reduced innovation capacity and a weakened climate for open communication and learning (Connelly et al., 2012; Jeong et al., 2022).

To explain KHB’s influence on organizational innovation, we draw upon two prominent and interconnected theoretical frameworks—namely, organizational learning theory and the social capital perspective. Although these theoretical frameworks are distinct, they converge in explaining how KHBs ultimately impair innovation capacity (Argote et al., 2011; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). Integrating these perspectives offers a more comprehensive understanding of how KHB undermines organizational innovation than either theory could provide independently (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

Organizational learning theory (Argote et al., 2011) provides a framework for understanding why KHB impedes the collective generation and refinement of new ideas. Per this perspective, the continuous sharing of experiential lessons, best practices, and emergent insights is integral to innovation. However, when individuals conceal information, it disrupts the channels needed for accumulating, disseminating, and applying knowledge critical to exploration and exploitation (Jansen et al., 2006). Such withholding undermines collaborative efforts and delays the identification of opportunities and risks, affecting incremental and radical innovation (Wright & McMahan, 1992; Randhawa et al., 2017; Goffin & Mitchell, 2016).

From an organizational learning perspective, KHB disrupts the following three critical learning processes that are essential for innovation (Argote & Miron-Spektor, 2011; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). First, it inhibits knowledge creation by preventing the integration of diverse perspectives and expertise that typically generate novel insights (Jansen et al., 2006; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). Second, it impedes knowledge transfer by blocking information flow across organizational boundaries and hierarchies, thus constraining the diffusion of innovative ideas (Argote et al., 2011; Szulanski, 1996). Third, it obstructs knowledge integration by limiting organizations’ ability to synthesize distributed knowledge into coherent innovations (Grant, 1996; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). These disruptions directly impact the learning cycles that allow organizations to develop novel products, services, and processes (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001; Utterback & Abernathy, 1975).

The social capital perspective elucidates how reciprocal trust and cohesive relationships enable organizations to leverage their intellectual assets for creative outcomes (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). In a high-trust environment, employees are encouraged to offer unique ideas and relevant expertise uninhibitedly, driving synergies that can stimulate innovative breakthroughs (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). However, once KHB becomes the norm, employees respond accordingly, systematically eroding social capital (Connelly et al., 2012). As these relational bonds weaken, coordinating the complex interdependencies involved in sustaining product and process innovation becomes increasingly challenging (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001). In this manner, KHB undermines both information flow and the relational foundation crucial for continuous adaptation.

The social capital perspective complements organizational learning theory by highlighting how KHB damages the relational infrastructure necessary for learning processes (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). KHB also undermines the following three social capital dimensions that are vital for innovation. Structurally, it weakens network connections that facilitate information exchange across organizational boundaries (Burt, 2004; Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). Relationally, it erodes trust and reciprocity norms that promote voluntary knowledge contributions (Leana & Van Buren, 1999; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). Cognitively, it prevents the development of shared mental models and a common understanding that enable collaborative problem-solving (Inkpen & Tsang, 2005; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). Additionally, KHB creates collaborative impediments that can directly impair innovation’s social foundations (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998; Zheng, 2010).

From a multi-level perspective, individual-level behaviors have emergent characteristics that shape higher-level outcomes (Kozlowski & Klein, 2000). When numerous employees engage in KHB, the resulting culture of withholding information gradually becomes a shared feature of the organizational environment (Connelly et al., 2012; Klein & Kozlowski, 2000), disrupting the collective routines and social capital required for ongoing innovation (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). In essence, fearing reciprocal withholding, employees’ inclination to volunteer creative solutions and experiment with novel ideas reduces, thus weakening the generative processes driving organizational renewal (Jansen et al., 2006). Consequently, a micro-level KHB climate exerts macro-level effects by limiting a firm’s ability to harness, integrate, and exploit employees’ diverse skill sets (Danneels, 2002; Kozlowski & Klein, 2000).

Integrating organizational learning theory with the social capital perspective provides a more robust explanation of how KHB impairs innovation than either framework could independently (Inkpen & Tsang, 2005; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). These perspectives converge on the following mechanisms: Organizational learning theory emphasizes how KHB disrupts the cognitive processes of knowledge creation, transfer, and integration, while the social capital perspective elucidates how it damages the relational infrastructure necessary for these processes to occur (Argote et al., 2011; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). Collectively, they illustrate how KHB fosters the process inefficiencies (from a learning perspective) and collaborative barriers (from a social capital perspective) that collectively undermine innovation capacity (Jansen et al., 2006; Zheng, 2010).

Furthermore, this theoretical integration helps explain why KHB affects multiple innovation types. First, it mitigates incremental innovation by preventing the refinement and extension of current capabilities, which typically build on existing knowledge (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001; Jansen et al., 2006). Second, it inhibits radical innovation, which generally requires novel combinations of diverse knowledge, cross-functional collaboration, and unconventional thinking to propel breakthrough developments (Danneels, 2002; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). By impairing both innovation types, KHB comprehensively undermines an organization’s ability to adapt and evolve within competitive environments (Argote & Miron-Spektor, 2011; Utterback & Abernathy, 1975).

Hence, KHB’s aggregated influence impedes a firm’s exploration of new opportunities and exploitation of existing capabilities, which are two key pillars of sustainable innovation (Mohr et al., 2022; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). As employees withhold valuable data and insights, organizational learning loops become fragmented, and avenues for creative collaboration diminish (Ocampo et al., 2020).

Collectively, these arguments suggest that individual-level KHB, when prevalent across a critical mass of employees, significantly impedes an organization’s innovation. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4 KHB decreases innovation.

Notably, SET offers a unifying framework for understanding how OPP, PCB, KHB, and organizational innovation are interlinked. Drawing on the seminal works of Homans (1961) and Blau (1964), SET theoretically elucidates how demands for perfection influence employee perceptions and behaviors, ultimately impacting innovation. Homans (1961) proposed that individuals continuously evaluate the profitability of their exchange relationships, helping to explain why perfectionist organizational demands trigger employees to adjust their contributions. Particularly, employees naturally shift these contributions to restore balance when organizational demands for perfection foster what Homas defines as ‘distributive injustice,’ wherein rewards are not proportional to efforts.

Blau’s (1964) emphasis on the unspecified nature of social exchange obligations is relevant to innovation, where knowledge sharing represents an investment with uncertain returns. In this regard, Blau noted: “The basic and most crucial distinction is that social exchange entails unspecified obligations, the fulfillment of which depends on trust because it cannot be enforced in the absence of a binding contract” (Blau, 1964, p. 112). This uncertainty makes knowledge exchange especially vulnerable to perceived PCB, as employees are reluctant to contribute when the exchange’s reciprocal nature appears compromised. In innovation-focused activities, where outcomes are often unpredictable and the value of knowledge contributions is not immediately apparent, this uncertainty is amplified, thus increasing trust’s significance in the exchange relationship.

At its core, SET posits that employment revolves around mutual obligations that, if perceived as violated, alter employees’ engagement with their organizational environment (Alcover et al., 2017; Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2019; Shore et al., 2006). The sequential mediation model that we propose aligns with Cook and Emerson’s (1978) ‘longitudinal exchange relations’ aspect of SET, which fosters chains of reciprocity or, in some cases, negative reciprocity when organizational demands are considered excessive relative to organizational support. When rigid performance standards are imposed on a workforce without adequate support (conditions that characterize OPP), employees may regard the organization as failing to fulfill their commitment to enabling employees to produce high-quality work (Kim et al., 2024). In such a situation, trust deteriorates and prompts employees to appraise their contribution–reward balance more critically.

Within this theoretical perspective, PCB represents the first mechanism that demonstrates OPP’s adverse impact on innovation (Rousseau et al., 2018). If employees believe that the organization enforces unrealistic demands while failing to fulfill implied agreements regarding fairness or resource allocation, their conviction that the employer has failed to uphold promises intensifies (Zhao et al., 2007). This recognition of PCB erodes any sense of mutuality and precipitates self-protective responses. In this regard, KHB emerges as a salient form of self-protection, whereby employees intentionally withhold information and insights (Connelly et al., 2012). Per this perspective, refusal to exchange knowledge is an adaptive yet counterproductive attempt to restore equity by minimizing discretionary contributions to a relationship that is considered inequitable (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Jeong et al., 2022).

KH can also result in decreased innovation as it depends on collaborative information exchange, brainstorming, and the collective refinement of ideas (Argote & Miron-Spektor, 2011). As employees increasingly withdraw their expertise, knowledge flows become fragmented and creative synergies deteriorate. This ripple effect highlights why an initial sense of organizational PCB ultimately resonates through subsequent withholding behaviors, thus limiting the development of novel processes and products (Siachou et al., 2021). Essentially, employees facing unrelenting perfectionist pressures may resent the perceived imbalance in the social exchange, causing them to impede the information flow necessary for an innovation-oriented climate.

Drawing on these perspectives, we propose a sequential mediation model, such that OPP first stimulates PCB, which then results in KHB, ultimately diminishing an organization’s innovation. Hence, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 5 PCB and KHB sequentially mediate the relationship between OPP and innovation.

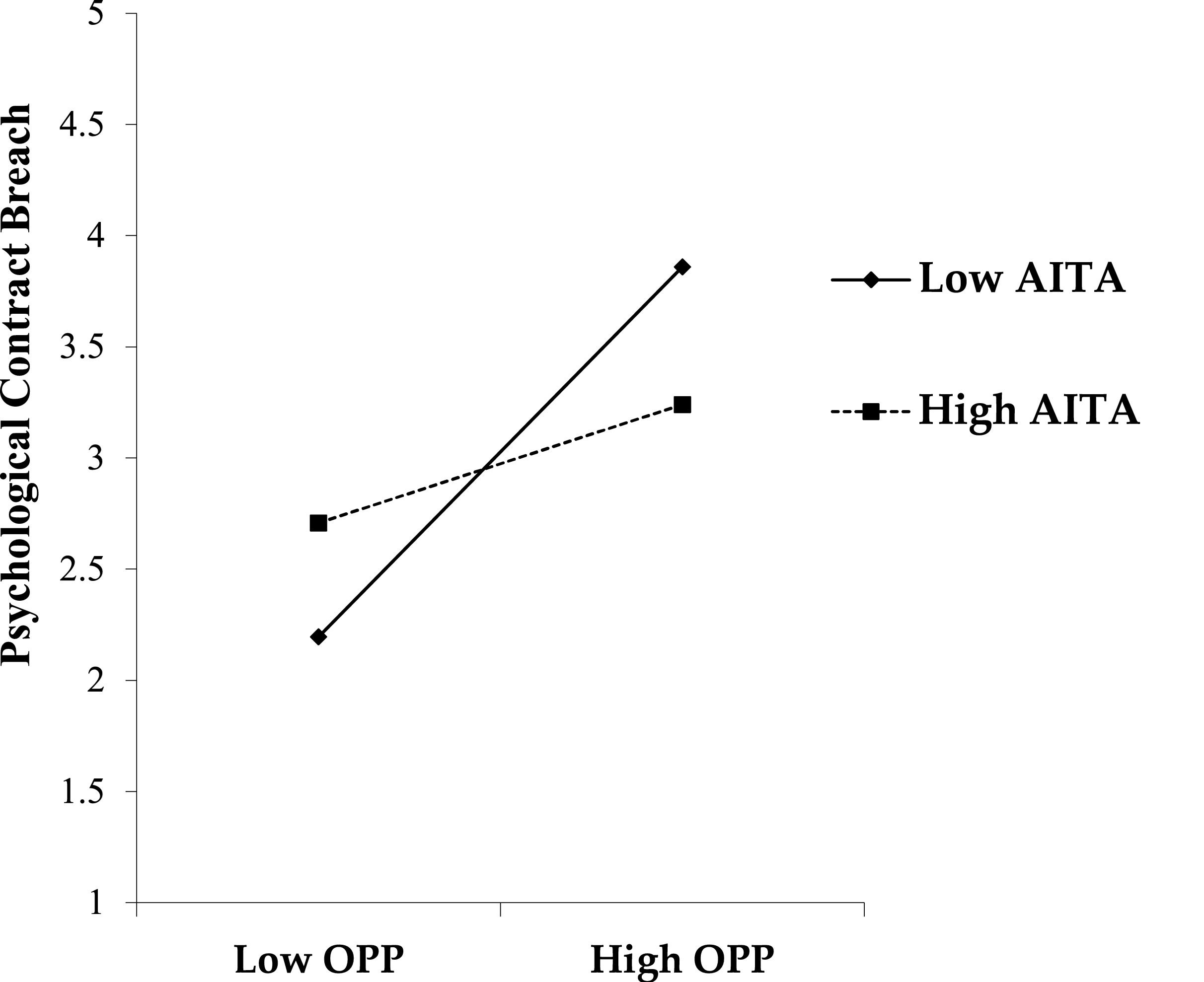

This study posits that AITA functions as a moderating variable by alleviating OPP’s adverse effects on PCB. As discussed, OPP potentially increases PCB. However, it is essential to acknowledge that the degree to which OPP impacts PCB differs depending on the organizational setting.

Generally, AI refers to a machine’s ability to imitate intelligent human behavior, encompassing various technologies that perform tasks that typically necessitate human intellect, including learning from experience, recognizing patterns, understanding language, making decisions, and solving complex problems (Russell & Norvig, 2021; Kaplan & Haenlein, 2019). In the modern organizational context, AI manifests in various forms, from sophisticated algorithms analyzing vast datasets for strategic insights to automated systems managing routine operational processes. For instance, these forms can include an AI-powered customer service chatbot that handles inquiries and resolves common issues, freeing up human agents for more complex interactions, or an AI-driven analytics platform that helps marketing teams identify emerging trends and personalize campaigns. Broadly, AITA refers to employees’ willingness to adopt and utilize AI-based systems for tasks such as decision-making, problem-solving, and process automation. Earlier conceptual frameworks, most notably the technology acceptance model, have emphasized perceived usefulness and ease of use as critical drivers of an individual’s intention to embrace novel technologies (Davis, 1989). Although these constructs remain influential in understanding technology adoption at a basic level, researchers have refined and extended them to account for social influence, perceived behavioral control, and facilitating conditions, as exemplified in the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Furthermore, studies on innovation diffusion (Rogers, 2003) and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) have highlighted the roles of subjective norms, attitudes, and ongoing interactions among organizational members.

Contemporary discussions on AI acceptance have underscored the multiple factors unique to AI that transcend traditional technology adoption considerations. For instance, algorithmic transparency and system trust have emerged as pivotal concerns as AI frequently operates in ways that users cannot easily interpret (Glikson & Woolley, 2020). Thus, employees may be wary of allowing algorithmic outputs to guide work practices if they do not comprehend how the system processes information, or if they suspect it might replace human roles (Brougham & Haar, 2020). Previous studies have also indicated that employees embrace AI when they expect tangible improvements in productivity and accuracy, or when such systems complement, rather than threaten, their core competencies (Cheng et al., 2023; Pan & Froese, 2023). Organizational support structures, including training programs, leadership endorsement, and a culture of open communication, facilitate smoother AI adoption, as users gain confidence in the technology and the organization’s broader vision for its implementation (Dwivedi et al., 2021; Makridis & Mishra, 2022).

In this study, we posit that AITA moderates OPP’s detrimental influence on employees’ perceptions of PCB. Drawing on the JD-R framework, technology acceptance may serve as an additional resource that helps employees cope with the demanding performance requirements imposed by an organization (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). When individuals feel comfortable and competent in using AI tools, their likelihood of perceiving these systems as enablers that mitigate task complexity and alleviate workload pressures increases, thereby buffering the negative impact of continuous demands for perfection (Dwivedi et al., 2021; Pan & Froese, 2023). Conversely, if employees lack confidence in AI solutions, they may perceive AI as amplifying the organization’s already strenuous expectations, intensifying their perceptions of unfairness and PCB.

When AITA is high, employees typically regard AI-driven systems as cooperative partners that enhance efficiency and offer real-time guidance. For instance, a marketing specialist might employ AI-based analytics tools to streamline repetitive data analysis, freeing up mental and temporal resources to fulfill stringent organizational standards without feeling overwhelmed. In such contexts, the employee is less likely to infer the employer’s perfectionist standards as excessive or unbalanced due to a supportive infrastructure that offsets heightened expectations (Brougham & Haar, 2020). Consequently, the likelihood of perceiving a breach in implied obligations decreases as the organization appears to supply the resources necessary to satisfy stringent performance criteria.

Conversely, when AITA is low, the same perfectionist standards yield a pronounced sense of inequity and frustration. For example, a product designer who lacks trust in AI-assisted prototyping tools may interpret the push for flawless product iterations as burdensome or unrealistic, believing that the organization expects these outcomes while failing to offer meaningful technological support. Such employees view demands for perfection as inconsistent with the implied organizational promises of a manageable workload, increasing the likelihood of PCB, as they interpret insufficient or underutilized AI resources as evidence that the firm has failed to fulfill its implied promises of equitable working conditions.

A growing body of empirical evidence strongly substantiates the assertion that low AITA exacerbates negative workplace outcomes, including feelings of overload and reduced collaboration. Brougham and Haar’s (2020) multi-country study demonstrated that employees with low technological acceptance report significantly higher levels of job-related stress and perceived workload when facing technological changes. Kim and Lee’s (2024) study on AI adoption further supports this connection, noting that employees with low self-efficacy regarding AI often experience heightened psychological strain and burnout symptoms when confronting AI implementation initiatives. That is, these employees perceive organizational performance expectations as more burdensome owing to their lower confidence in leveraging AI tools effectively.

Multiple studies have empirically documented low AITA’s negative impact on collaborative behaviors. For instance, Wu et al. (2022) found that employees exhibiting resistance to AI technologies experience greater job insecurity and engage less in collaborative behaviors in human–machine work environments. Extending these findings, Kim et al. (2024) demonstrated that AI-induced job insecurity significantly disrupts cooperative workplace dynamics, with employees exhibiting greater reluctance to share resources and expertise with colleagues. Likewise, Kim and Kim (2024b) empirically established that AI-related insecurities result in KHB, though this effect is significantly weaker among employees with higher AI self-efficacy.

Notably, Kim and Lee (2025) documented how AI implementation challenges foster additional psychological impediments that heighten perceptions of work intensity, particularly when organizational support mechanisms fail to address employees’ technological adaptation concerns. They found that employees struggling with AI adoption perceive more pressure when facing organizational performance demands, thus increasing feelings of psychological contract violation.

Bankins et al. (2024) comprehensively reviewed AI’s organizational impact and identified that employees’ reluctance to engage with AI tools precipitated additional cognitive burdens as they attempted to navigate between traditional and AI-augmented work processes, resulting in increased perceptions of overload. Furthermore, Endsley’s (2023) study on human–AI teams revealed that limited AITA disrupts collaborative team dynamics, as employees who distrust AI systems are less likely to share information or depend on AI-generated insights, thereby fragmenting knowledge flows within teams. Additionally, Zirar et al. (2023) found that the unsuccessful integration of AI technologies owing to employee resistance creates organizational tensions that increase individual workloads and reduce cross-functional collaboration.

Collectively, these findings provide substantial empirical evidence that low AITA exacerbates feelings of work overload, heightens perceptions of PCB, and impedes collaborative knowledge-sharing, particularly in contexts characterized by demanding performance expectations.

Thus, AITA functions as a vital moderator in the relationship between OPP and PCB by mitigating the extent to which demanding perfectionist norms are perceived as unfair or unsupported (Fig. 1).

Hypothesis 6 AITA moderates the relationship between OPP and PCB, such that the positive relationship is weaker when AITA is high and stronger when AITA is low.

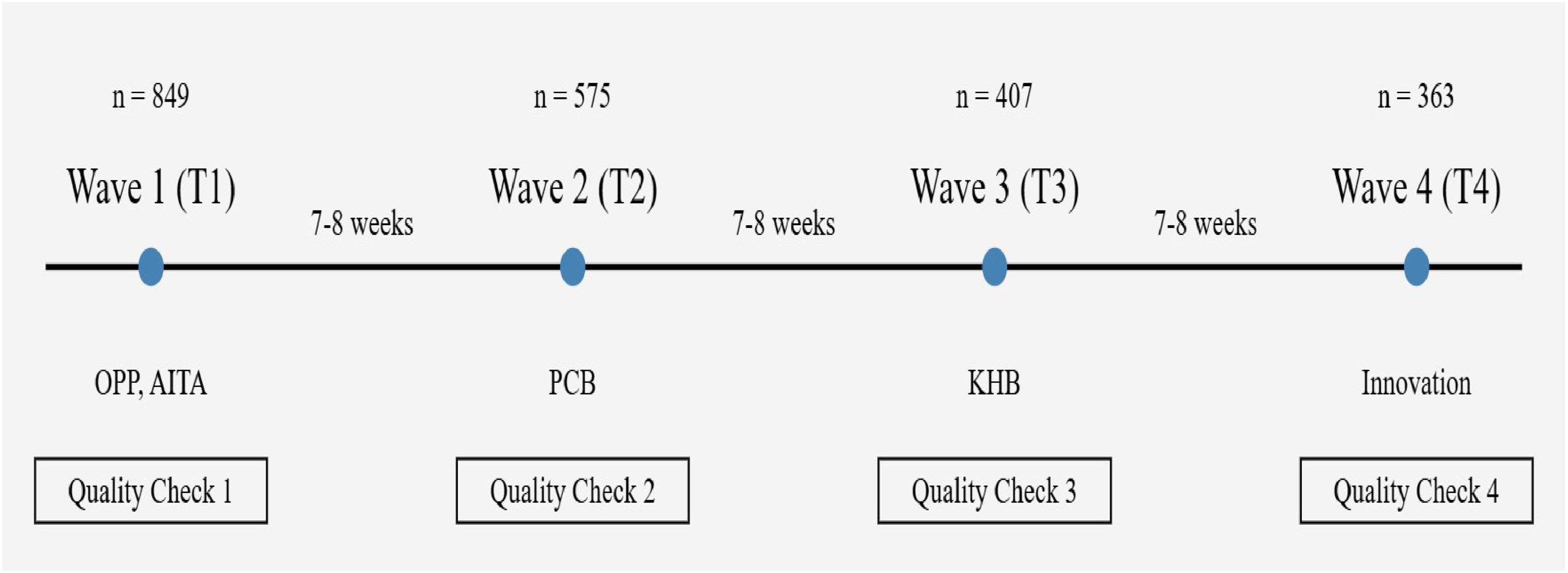

A four-wave, time-lagged research design was employed to examine the intricate links among OPP, AITA, PCB, KHB, and innovation based on several methodological considerations, elucidated as follows. First, this design significantly mitigates common method bias by temporally separating the measurement of predictor and criterion variables (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Second, our sequential mediation model theorizes a causal chain (OPP → PCB → KHB → Innovation) that unfolds over time, making a time-lagged design with seven-to-eight-week intervals between measurements more appropriate than cross-sectional approaches for capturing these developmental processes (Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Third, this approach enables an examination of how initial perceptions (i.e., of OPP and AITA at T1) influence subsequent psychological states (i.e., PCB at T2), which, in turn, affect behaviors (i.e., KHB at T3) and, ultimately, organizational outcomes (i.e., innovation at T4). This design deliberately spans a sufficiently long interval to allow the hypothesized processes to unfold within a realistic workplace context while also minimizing dropout rates, which can reduce the final dataset’s representativeness (Dormann & Griffin, 2015).

This study employed a stratified random sampling approach to ensure representative coverage across key demographic variables. The sampling frame comprised a national online research panel maintained by a research company, encompassing approximately 5.89 million registered adults throughout South Korea. Based on national workforce statistics, we first stratified this panel by gender, age (20–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50–59 years), educational attainment, organizational position, and industry sector. Next, we randomly selected potential participants from each stratum, with selection probabilities proportional to the national workforce distribution. Initial invitations were sent to 2500 panel members who fulfilled our inclusion criterion—specifically, current employment in an organization with at least five employees. From this pool, 849 individuals (34 % response rate) participated in the first wave of data collection. Existing studies have substantiated the reliability and breadth of digital surveys for assembling large, representative samples (Landers & Behrend, 2015).

Data collection proceeded systematically across four waves. In the initial wave (T1), 849 employees provided data on OPP and AITA. During this phase, robust procedures, such as verifying IP addresses and monitoring the amount of time spent responding to the survey, were employed to ensure quality and authenticity. The second wave (T2), which was conducted approximately seven to eight weeks after T1, involved 575 employees who submitted PCB ratings, supported by participant checks and an analysis of response patterns. The third wave (T3) was also administered seven to eight weeks later and gathered data on KHB from 407 participants. The final wave (T4) was conducted roughly seven to eight weeks after T3 and yielded innovation measures from 363 participants over a two-to-three-day window to ensure a balance between participant accessibility and data integrity. Additionally, the dependent variable (innovation) was collected from department heads rather than individual employees in the final wave to help avoid single-source bias while capturing this outcome’s organizational-level nature (Wright & McMahan, 1992).

This study’s reference population comprises approximately 27.6 million employed adults in South Korea (Statistics Korea, 2023). Our final sample of 363 participants (after accounting for attrition across waves) exceeds the minimum requirement of 359 participants, as determined by a GPower analysis for detecting medium effect sizes (f² = 0.17), with an alpha level of 0.05 and power of 0.95. Furthermore, demographic analysis revealed that our sample adequately represents the national workforce, with comparable distributions of gender (49.0 % male in our sample versus 48.7 % nationally), age cohorts (21.5 %, 21.8 %, 28.1 %, and 28.7 % for age groups 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50–59, respectively, compared to 20.3 %, 22.7 %, 27.3 %, and 29.7 % nationally), and industry representation. This demographic alignment enhances our findings’ generalizability to the broader South Korean working population. Quality control tactics encompassed geo-IP checking, survey duration verification, and multi-stage participant validation. Before commencing the survey, participants’ employment status was verified via mobile or email verification. Appropriate informed consent procedures were followed, and each participant received between $12 and $13 as compensation for their time and effort.

Once the surveys were completed, an extensive validation and cleaning protocol was implemented to preserve data integrity. This process involved discarding incomplete or inconsistent records, identifying irregular response patterns, and cross-referencing entries across each wave to ensure legitimacy. Ultimately, 363 valid cases were retained, reflecting a 42.76 % completion rate (363/849), which is consistent with established benchmarks for multi-wave research in organizational contexts. An attrition analysis revealed no significant demographic or substantive differences between participants who participated in all waves and those who discontinued prematurely, indicating that attrition did not induce systematic bias in the final sample.

Collectively, these processes helped guarantee that the findings accurately reflect the observed phenomena and mitigate common threats to validity and reliability. In conjunction with meticulous screening and thorough data-verification procedures, the multi-wave, time-lagged structure provides a robust methodological foundation for analyzing how OPP, AITA, PCB, KHB, and innovation interrelate within organizational environments (Fig. 2, Table 1a).

Descriptive Characteristics of the Study Sample.

At T1, participants responded regarding their experiences with OPP and the degree to which AITA was prevalent in their workplace. At T2, they discussed their perceptions of PCB, and at T3, they evaluated the prevalence of KHB. Finally, at T4, data regarding the degree of organizational innovation were collected from directors of human resource management departments. All constructs were evaluated using multi-item scales, and participant responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale.

OPP (T1)This study assessed OPP using six items adapted from the Socially Prescribed Perfectionism subscale of the MPS (Hewitt & Flett, 1991), which was then revised to align with the organizational domain. We acknowledge that this adaptation modifies the original scale to suit our specific research context, which may impact the construct’s psychometric properties. The original scale measured perceptions of the excessively high expectations and critical judgments of others. However, the items from this scale were systematically modified to reflect OPP by replacing ‘others’ with ‘organization’ or ‘my organization’ in each item, thus maintaining the semantic structure while altering the source of perfectionist demands. While we recognize that such adaptations may alter the construct’s underlying dimensionality, our confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) supported the adapted scale’s unidimensional structure. Additionally, the six items were derived from existing studies that have utilized this variable (Kim et al., 2024; Kim & Lee, 2025). The full items include the following: “My organization expects me to succeed at everything I do,” “I find it difficult to meet my organization’s expectations of me,” “My organization readily accepts that I can make mistakes too (reverse-scored),” “My organization expects me to be perfect,” “My organization expects more from me than I am capable of giving,” and “People in my organization still think I am competent even if I make a mistake (reverse-scored).” This scale’s reliability, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.829.

AITA (T1)This study assessed participants’ AITA using a modified version of the UTAUT framework, originally proposed by Venkatesh et al. (2003). This scale comprised the following six sub-constructs: (1) performance expectancy, (2) effort expectancy, (3) attitudes toward using technology, (4) social influence, (5) facilitating conditions, and (6) self-efficacy. Each of these sub-constructs was measured using three items, totaling 18 items to gauge overall AITA. These items were adapted from the original UTAUT scales to reflect the context of generative AI technology.

The specific items utilized for each sub-construct are detailed as follows: (1) The performance expectancy subscale included “I would find generative AI technology useful in my job,” “Using generative AI technology enables me to accomplish tasks more quickly,” and “Using generative AI technology increases my productivity.” (2) The effort expectancy subscale included “It would be easy for me to become skillful at using generative AI technology,” “I would find generative AI technology easy to use,” and “Learning to operate generative AI technology is easy for me.” (3) The attitudes toward using technology subscale included “I like working with generative AI technology,” “Working with generative AI technology is fun,” and “Generative AI technology makes work more interesting.” (4) The social influence subscale included “People who influence my behavior think that I should use generative AI technology,” “The senior management of this business has been helpful in promoting the use of generative AI technology,” and “People who are important to me think that I should use generative AI technology.” (5) The facilitating conditions subscale included “I have the resources necessary to use generative AI technology,” “A specific person (or group) is available for assistance with difficulties related generative AI technology,” and “I have the knowledge necessary to use generative AI technology.” (6) The self-efficacy subscale included “By utilizing generative AI technology, I can achieve the objectives set forth in my professional endeavors,” “I can utilize generative AI technology to perform my job effectively even when the situation is challenging,” and “I can complete my tasks using generative AI technology without any help.” This measure exhibited a Cronbach’s α of 0.932.

PCB (T2)This study measured PCB using five items, adapted from prior studies (Coyle-Shapiro & Kessler, 2000). The questions included the following: “Almost all the promises made by my employer during recruitment have not been kept thus far,” “I have not received everything promised to me in exchange for my contributions,” “My employer has broken many of its promises to me even though I’ve upheld my side of the deal,” “I feel betrayed by my organization,” and “I feel that my organization has violated the contract between us.” This measure exhibited a Cronbach’s α of 0.924.

KHB (T3)This study measured KHB using five items extracted from the original eleven-item KHB scale (Connelly et al., 2012). Prior investigations within the South Korean context (Jeong et al., 2022, 2023) have validated the use of these five items, specifically, “I offer my colleagues different information from what they really want,” “I agree to help them but instead give them different information from what they want,” “I pretend that I do not know the information,” “I explain that the information is confidential and only available to people on a particular project,” and “I tell them that my boss would not let anyone share this knowledge.” The Cronbach’s alpha for these five items was 0.921, indicating excellent reliability.

Innovation (T4)This study assessed the degree of innovation within participating organizations by administering a survey to the director of each company’s human resource management department. This approach attempts to capture an organizational-level perspective on innovation, as these directors typically possess a broad view of the organization’s practices and capabilities (Wright & McMahan, 1992). The survey instrument included four items designed to capture the key facets of organizational innovation, such as idea generation, implementation, and overall organizational support for innovation.

These items were developed by adapting measures utilized in prior research on organizational innovation, including studies on the different aspects of innovative capabilities and practices (e.g., Jansen et al., 2006; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005), focusing on dimensions associated with product and process innovation (Danneels, 2002; Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001), and the dynamic relationship between these two (Utterback & Abernathy, 1975). In adopting these items, we aimed to holistically measure organizational innovation, reflecting a firm’s ability to generate and implement novel improvements. The specific items were as follows: “Our organization is highly effective at generating new ideas for improving our existing products and services,” “Our organization is highly effective at implementing new product and service improvements,” “Our organization frequently introduces products and services that are significantly improved versions of our existing offerings,” and “Our organization fosters a culture that encourages creativity and the implementation of new ideas.” The Cronbach’s alpha for these five items was 0.931, indicating excellent reliability.

Control variablesConsistent with established methodological guidelines (Becker et al., 2016), this study incorporated various control variables at the individual and organizational levels to account for alternative explanations of KHB and the degree of innovation. At the organizational level, industry type and firm size were controlled as these contextual attributes influence the baseline conditions for innovation (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001; Jansen et al., 2006). Certain industries, such as high-tech manufacturing, may experience rapidly shifting market demands that necessitate more frequent product or process innovation (Danneels, 2002). Likewise, larger firms typically possess broader resource pools, enabling higher R&D investment, though extensive bureaucratic structures occasionally impede knowledge flows (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005).