Patient safety culture is an essential factor in the decreasing of medical errors and development of the institutions. This study was conducted to determine to what extent the selected variables, including age, weekly working hours, years of experience, burnout, turnover intention, workload, and job satisfaction, predict perceived patient safety culture among emergency nurses in Jordanian hospitals.

MethodsA cross-sectional design with convenience sampling approach was used. A total of 157 emergency nurses from governmental and public hospitals were participated in the study and completed the study's survey: Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (PSC), Copenhagen Burnout Inventory–Student Survey (CBI–SS), NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), Nursing Workplace Satisfaction Questionnaire (NWSQ) and turnover intention scale (TIS).

ResultsThe results showed that there was a negative relationship found between nurses’ age and PSC perception (r=−.166, P=.039), personal burnout and PSC (r=−.160, P=.048), and there was also a negative relationship between turnover intentions and perceived PSC (r=−.334, P=.000). The results from the regression model indicated that turnover intentions, reporting patient safety events, and the number of events reported predicted PSC. The results showed that R2=.29, adjusted R2=.287, F(6,141)=9.45, P<0.01.

ConclusionOur results suggests that nurses’ managers may pay attention to decreasing burnout and analyze turnover intention among nurses in order to improve the culture of patient safety.

La cultura de seguridad del paciente es un factor esencial para reducir los errores médicos y el desarrollo de las instituciones. Este estudio fue realizado para determinar en qué medida predijeron la cultura de seguridad del paciente percibidas las variables seleccionadas tales como edad, horas de trabajo semanales, años de experiencia, agotamiento profesional (burnout), planes de rotación, carga de trabajo y satisfacción laboral entre las enfermeras de urgencias de los hospitales jordanos.

MétodosSe utilizó un diseño transversal con enfoque de muestreo de conveniencia. Participaron en el estudio un total de 157 enfermeras de urgencias procedentes de hospitales gubernamentales y públicos, quienes completaron las encuestas del estudio: encuesta del hospital sobre la cultura de seguridad del paciente (PSC), Copenhagen Burnout Inventory–Student Survey, NASA Task Load Index, Nursing Workplace Satisfaction Questionnaire y Turnover intention scale.

ResultadosLos resultados reflejaron que existió una relación negativa entre la edad de las enfermeras y la percepción de PSC (r = -0,166, P = 0,039), burnout personal y PSC (r = -0,160, P = 0,048), y también una relación negativa entre los planes de rotación y la PSC percibida (r = -0,334, P = 0,000). Los resultados del modelo de regresión indicaron que los planes de rotación, el reporte de los episodios de seguridad del paciente, y el número de episodios reportados predijeron la PSC. Los resultados reflejaron que R2 = 0,29, R2 ajustada = 0,287, F (6.141) = 9,45, p < 0,01.

ConclusiónNuestros resultados sugieren que los directores de las enfermeras deben prestar atención a la reducción del burnout y analizar los planes de rotación entre las enfermeras, a fin de mejorar la cultura de seguridad del paciente.

Patient safety is defined as the avoidance of mistakes and adverse effects associated with patients in a health-care settings.1 Safety culture is considered to be a central aspect of organizational culture, institutions’ development and safety performance, which has an important impact on staff attitudes and behavior.2 It is based on the values, perceptions, abilities and patterns of behaviors of individuals and groups.3 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) emphasizes the importance of patient safety development and the improvement of safety culture through the development of patient safety culture (PSC) in health-care organizations.4 Previous literature shows that PSC is an essential measure used to evaluate the quality of health care5 and to decrease missed nursing care.6 Common deficits in PSC occur in health-care settings resulting from poor communication structures, leadership, and teamwork as well as inadequate staff knowledge about safety processes, unsupportive safety culture in health care and the absence of reporting and analysis systems regarding adverse events.7 Assessment of perceived PSC is a central focus of health-care organizations.8 When nurses identify patient safety, they become much more confident in challenging problems related to safety issues and more positive toward PSC.9 Establishing PSC is an important way and the first priority to improve the nurse–patient relationship. In order to improve PSC, hospital managements conduct hospital surveys, observe strength and weakness factors affecting PSC from the nurses’ perceptions, then take appropriate actions to enhance advantages and address deficiencies.10 Safety culture is associated with more positive patient experiences, such as an increase in patients’ feeling of care.11

Burnout is a common concept among emergency nurses and is composed of three main dimensions, namely emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and reduced personal accomplishment (PA). Emotional exhaustion is the degree of tiredness and harm to emotional state, depersonalization is a measure of depraved sights toward patients, and reduced PA is the amount of decrease in the level of competence and productivity.12,13 Gómez-Urquiza, Emilia, Albendín-García, Vargas-Pecino, Ortega-Campos, Cañadas-De la Fuente14 conducted a meta-analysis of 13 studies to view the incidence of each of the three subscales of burnout among emergency nurses. There was a high influence of EE related to poor work circumstances, inadequate time to develop caring activities and an extreme workload. The DP also showed high occurrences in which the most affected subscale related to excessive working hours and absence of assertiveness. The reduced PA was aggravated by a lack of assertiveness and was perhaps considered as a consequence of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. In Jordan, three subscales of burnout were found to be at moderate levels among nurses, but EE showed the highest mean score and the serious sign of burnout dimensions among nurses.15 Several studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between burnout and overall perception of PSC. For instance, a study conducted in Oman explored the effect of nursing burnout on PSC. A total of 270 nurses from two major governmental hospitals who work in critical care units participated. The results showed that there was a negative relationship among overall perception of PSC and EE as well as DP,16 which corresponds with the findings of a study conducted by Johnson et al.17 In another example – a cross-sectional study conducted in ICUs in Norway that explored the relationship between burnout and PSC – 143 out of 289 registered nurses participated and results showed that a low score for burnout was significantly correlated with the overall perception of PSC.18

Turnover intention is defined as the thought process of an individual who desires to leave their work because of dissatisfaction with it.19 It refers to the likelihood of an employee to willingly leave the job within a specific period of time20 and is considered as a common problem in organizations around the world, especially among health care providers,21 and among nurses in the USA and worldwide.22 In the literature, turnover intention was measured by asking workers about their willingness to stay or leave their work.23,24

Nursing workload is all the accomplishments achieved by nurses within their work; it measures the quality of care.25 Workload shows a lot of nursing activities are required to be done during their shifts and these are classified as direct or indirect activities. Examples of direct activities are monitoring vital signs, administering medications, giving intravenous fluids and blood, dressing wounds, sending and receiving patients from operation rooms, educating family and patients, while the documentation process is a form of indirect nursing activities.25 Swiger et al.26 pointed out that bed occupancy, patients’ awareness, and availability of staff resources are also determined as a part of the nursing workload.

This study was conducted during the pandemic of COVID-19 in Jordan, COVID-19 it is a serious global health disaster that affecting healthcare workers (HCWs). During this pandemic; nurses as frontline HCWs are exposed to many stressors such as risk of infection, fear, anxiety, mental and physical stressor and workload.27 Furthermore, nurses are facing many challenges such as exposure of new disease, limited information about the virus, exhaustion due to workload, insufficient resources such as personal protective equipment (PPE).28 All these stressors and challenges might affecting the patient safety and job satisfaction. High workload of nurses is a major concern, therefore attention should be paid to the workload of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Job satisfaction is one of the major concerns of recent management. It involves employee improvement, productivity and competence through the qualifications they obtain from their job.29 It is used to measure the degree of a worker's comfort within their work30 and is considered as a balance between employee prospects and the advantages they receive from their organization.31 Health-care organizations hardly focus on workers’ job satisfaction.32 Development, work safety and respect are the major elements of nurses’ job satisfaction.33

Nurses differ in their demographic variables, concern to study demographic variables and their influence on overall perception of PSC among nurses working in EDs in Jordan. Nurse-related factors include (age, weekly working hours, and years of experience). Other studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between nurses’ age and their perception of PSC, four of which found that there was no relationship between these two variables.34–37 Otherwise, Elsous et al.38 showed that nurses over 35 years old had higher scores of overall PSC perception than nurses who were under 35 years old, because nurses over 35 years were more mature and responsible in their job. In addition, nurses in their forties and fifties recognized the problems and consequences associated with carelessness as well as being more aware of their responsibilities and roles towards patient safety.

This study was conducted to determine to what extent the selected variables, including age, weekly working hours, years of experience, burnout, turnover intention, workload, and job satisfaction, predict perceived patient safety culture among emergency nurses in Jordanian hospitals.

Materials and methodsStudy designA cross-sectional design with conveniences sampling approach was used to collect data.

Sample and procedureEthical approval was obtained from the research and ethics committees at AL-Zaytoonah University of Jordan on February 6, 2020. After that, ethical approvals were obtained from Al Khalidi Hospital and Medical Centre, the Arab Medical Centre, and the Ministry of Health (MOH) on 17 February 2020, 25 February 2020, and 27 February 2020, respectively. A brief meeting was held with the administrator of human resources in the above mentioned institutions to provide an explanation of the nature and purpose of the study and to obtain permission for distributing the self-reported questionnaires among nurses. The researcher ensured that the information sheet in the questionnaires included all the information about the study's purpose and methods. Study surveys were distributed and collected between February and April 2020. Participants who met the inclusion criteria were approached and participated in the current study: (1) Jordanian nurse; (2) worked in the emergency department; (3) was working full time; (4) consented to participating in the study; (5) had at least 6 months of clinical experience.

Study instrumentsFive valid and reliable instruments were used in the current study. The researches checked the instruments for cultural sensitivity before the implemented. The English versions of the instruments were used:

Hospital survey on patient safety culture (HSOPSC)HSOPSC was used to measure dimensions of PSC. It consists of 12 dimensions, including frequency of event reporting, supervisor or manager expectations, organizational learning and continuous improvement, teamwork within units, communication openness, feedback and communication of errors, non-punitive response to error, staffing, management support for patient safety, teamwork across hospital units, hands-off and transition. it has a five-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree, or 1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=most of the time, 5=always). It also included two questions that asked participants to give an overall grade on patient safety for their work area and to provide the number of events that had been reported over the past year.39

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory–Student Survey (CBI–SS)CBI–SS was used to measure the burnout among emergency nurses in Jordanian hospitals.40 It had19 questions that reflected three subdimesions of burnout comprising personal burnout (six items), work-related burnout (seven items) and client-related burnout (six items), with the following scale: 0=never, 25=rarely, 50=sometimes, 75=often, 100=always. The scale was valid and reliable with Cronbach's alpha (0.85–0.87).40

Turnover intention scale (TIS)Turnover intention scale (TIS) was used in the current study to assess the turnover intention variable among emergency nurses. It has 30 items on a six-point Likert-scale (1=totally disagree, 2=strongly disagree, 3=somewhat disagree, 4=somewhat agree, 5=strongly agree, 6=totally agree).41 The TIS score ranged from 30 (indicating no intention of turnover) to 180 (indicating maximum intention of turnover). The scale was valid and reliable with Cronbach's alpha 0.80.

NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX)Workload was assessed using NASA Task Load Index, which is a well-known subjective workload assessment questionnaire.42 It consists of six factors that influence workload (mental, temporal, physical demand, frustration, effort and performance), and each element is evaluated with a subjective judgment.43 The score of the NASA-TLX ranged from 0 (indicating no demand) to 100 (indicating maximum demand). According to this questionnaire, the minimum score is 0 and the maximum 600; 0 meaning that the participant had not had a workload, and a score of 600, meaning that the participant had obtained the highest workload level. Based on the findings of Hoonakker et al.44 the NASA-TLX is a reliable and valid tool with a Cronbach's alpha of the overall scale of 0.72.

Nursing Workplace Satisfaction Questionnaire (NWSQ)The Nursing Workplace Satisfaction Questionnaire (NWSQ) was intended for nurses and looking for job satisfaction as a result of a nursing care plan in a large Sydney hospital.45 It is short (one page) and has 17 items with a five-point Likert-scale (1=fully agree, 2=agree, 3=partly agree/disagree, 4=disagree, 5=definitely agree). According to this questionnaire, the minimum score is 17 and the maximum is 85; 17 meaning that the participant has the highest satisfaction score, whereas a score of 85 means that the lowest satisfaction score is obtained. The tool encompasses three measurable domains: intrinsic domain (six items), extrinsic domain (seven items) and relational domain (four items).45 This questionnaire was valid and reliable with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.90.46

Statistical analysisDescriptive analysis including mean (M), standard deviation (SD), frequency and percentages was performed to describe the sample characteristics. Mean and standard deviation were used to describe age, working hours, years of experience, and the scores of the study's variables, including burnout, workload, turnover intention, job satisfaction and dimensions of the patient safety culture scale. Frequency and percentages were used to describe gender, marital status, nurse's position and educational level. Multiple regression (R2) analysis was performed in the current study to identify to what extent the independent variables could predict the dependent variable (perceived patient safety culture) among emergency nurses in Jordan.

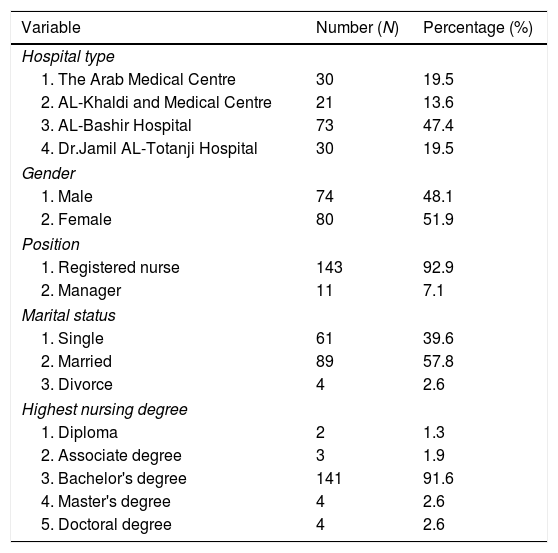

ResultsCharacteristics of the Study ParticipantsA total of 154 nurses completed and returned the study questionnaire. As shown in Table 1, 51.9% of participants were females (n=80), the mean of nurses’ age was 29.7 years (SD=5.92), more than half of the participants were married (57.8%, n=89). The majority of them had a bachelor's degree (N=141, 91.6%). The mean of years of experience was 4.68 years (SD=4.61). Table 1 details these results.

Participants’ characteristics; mean (M), standard deviation (SD) and percentages (%) among surveyed nurses (N=154).

| Variable | Number (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital type | ||

| 1. The Arab Medical Centre | 30 | 19.5 |

| 2. AL-Khaldi and Medical Centre | 21 | 13.6 |

| 3. AL-Bashir Hospital | 73 | 47.4 |

| 4. Dr.Jamil AL-Totanji Hospital | 30 | 19.5 |

| Gender | ||

| 1. Male | 74 | 48.1 |

| 2. Female | 80 | 51.9 |

| Position | ||

| 1. Registered nurse | 143 | 92.9 |

| 2. Manager | 11 | 7.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| 1. Single | 61 | 39.6 |

| 2. Married | 89 | 57.8 |

| 3. Divorce | 4 | 2.6 |

| Highest nursing degree | ||

| 1. Diploma | 2 | 1.3 |

| 2. Associate degree | 3 | 1.9 |

| 3. Bachelor's degree | 141 | 91.6 |

| 4. Master's degree | 4 | 2.6 |

| 5. Doctoral degree | 4 | 2.6 |

| Mean (M) | Standard deviation (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 29.70 | 5.92 |

| Working hours per week | 46.03 | 7.22 |

| Experience in emergency department | 4.68 | 4.61 |

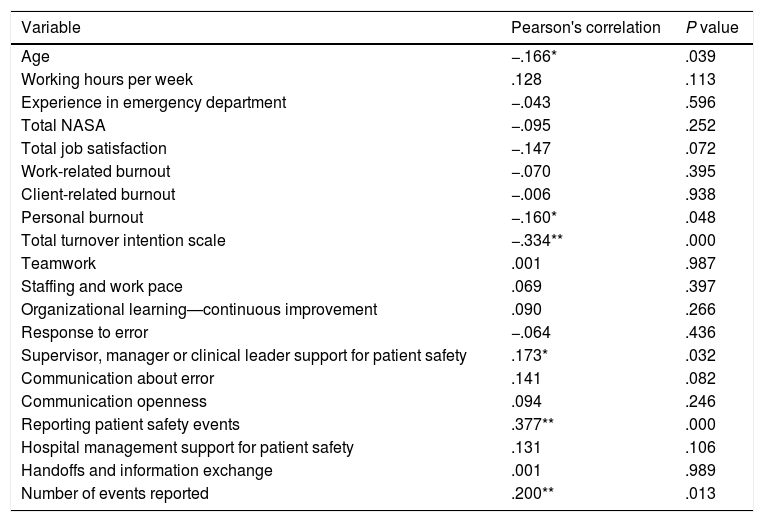

Pearson correlation coefficient was used to explore the relationships between study's variables. The results showed that there was a negative relationship found between nurses’ age and PSC perception (r=−.166, P=.039), personal burnout and PSC (r=−.160, P=.048), and there was also a negative relationship between turnover intentions and perceived PSC (r=−.334, P=.000). Conversely, a positive relationship was found between supervisor position and PSC (r=.173, P=.032). A positive relationship was also found between reporting the patient safety events and PSC (r=.377, P=.000). In addition, there was a positive relationship found between the number of events reported and PSC (r=.200, P=.013). Moreover, Pearson's correlation was computed to assess the relationship between items of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC) dimensions and overall perception of PSC. Table 2 details these results.

Pearson's correlation of the study variables (N=154).

| Variable | Pearson's correlation | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −.166* | .039 |

| Working hours per week | .128 | .113 |

| Experience in emergency department | −.043 | .596 |

| Total NASA | −.095 | .252 |

| Total job satisfaction | −.147 | .072 |

| Work-related burnout | −.070 | .395 |

| Client-related burnout | −.006 | .938 |

| Personal burnout | −.160* | .048 |

| Total turnover intention scale | −.334** | .000 |

| Teamwork | .001 | .987 |

| Staffing and work pace | .069 | .397 |

| Organizational learning—continuous improvement | .090 | .266 |

| Response to error | −.064 | .436 |

| Supervisor, manager or clinical leader support for patient safety | .173* | .032 |

| Communication about error | .141 | .082 |

| Communication openness | .094 | .246 |

| Reporting patient safety events | .377** | .000 |

| Hospital management support for patient safety | .131 | .106 |

| Handoffs and information exchange | .001 | .989 |

| Number of events reported | .200** | .013 |

Note: *r = −.160, **P = .048.

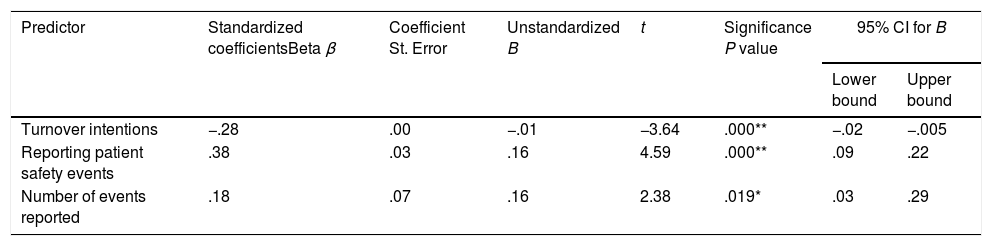

The e linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the significant predictors of PSC perception. The results from the parsimonious regression model indicated that turnover intentions, reporting patient safety events, and the number of events reported predicted PSC. The results showed that R2=.29, adjusted R2=.287, F(6,141)=9.45, P<0.01. In this model, reporting patient safety events had the most to contribute; in contrast, turnover intentions had the least impact. Finally, the above-mentioned independent variables accounted for 28.7% of the variance in PSC. Table 3 details these results.

Parsimonious regression model for PSC predictors (N=154).

| Predictor | Standardized coefficientsBeta β | Coefficient St. Error | Unstandardized B | t | Significance P value | 95% CI for B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| Turnover intentions | −.28 | .00 | −.01 | −3.64 | .000** | −.02 | −.005 |

| Reporting patient safety events | .38 | .03 | .16 | 4.59 | .000** | .09 | .22 |

| Number of events reported | .18 | .07 | .16 | 2.38 | .019* | .03 | .29 |

Note: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, β – beta, SE – standard error, CI – confidence interval.

This study was conducted to determine to what extent age, weekly working hours, years of experience, burnout, turnover intention, workload, and job satisfaction, predict perceived patient safety culture among emergency nurses in Jordanian hospitals.

The results of the current study found a significant negative correlation between personal burnout and overall PSC perception. This probably indicated that personal burnout results from a high workload; in our study, the mean working hours per week was 46. These findings are consistent with a study in Brazil conducted by Alves and Guirardello,47 in which the respondents had a low perception of PSC because they worked approximately 45h/week. This workload burden resulted from the respondents working overtime to increase their low incomes. Consistent with these findings, in another study, the nurses felt unconfident in their perception of PSC when they experienced a workload burden and could not finish their assignments, in spite of working hard to do their best.48

The findings from the current study indicated that the overall workload among nurses was very high. The results also showed that there was no relationship between nursing workload and overall perception of PSC. These findings might be related to the continued education of our participants, as they attended different workshops on time and job management, which were led by a specialist. Previous work by Ma’mari et al.16 stated that nurses’ workloads were not correlated with the overall perceptions of PSC in two hospitals in Oman, due to the staff in both hospitals working hours that did not exceed 40h/week, in addition to both hospitals fulfilling the nurse–patient ratio, which is 1:1 in critical care units, according to international guidance.49 In addition the nurses benefited from lectures explaining how to manage my work and time, as presented by a specialist.

Further findings from this study indicated that nurses’ satisfaction is not correlated with overall perception of PSC. One point of view is provided in a study by Kong et al.,50 who argued that nurses could recognize any unsafe conditions regarding patients’ safety unless satisfied with their colleagues, working environments and institutional policies. However, two studies by Bondevik et al.51 and Ooshaksaraie et al.,52 conducted in Norway and Iran, respectively, showed that job satisfaction was positively related to overall perception of PSC, that satisfied nurses worked hard to initiate quality improvement actions, which in turn improve PSC perception. In addition, it has been clarified that satisfied nurses had higher productivity and job commitment29,53 as well as contributing to lower adverse event incidents.54 They also improved the overall quality of health care, which resulted in the development of overall PSC perception.9

The results of this study showed that turnover intention was correlated negatively with the overall perception of PSC. This might be related to turnover intention leading to staff shortages and increased work stress, which affected negatively the quality of nursing care and decrease overall PSC perception. Our findings provided further support for results of similar studies conducted in other countries.55–57

The results of the current study indicated that nurses’ age had a negative correlation with the overall perception of PSC. Nurses’ age is an influential factor for their physical ability to perform their duties was safe and competent shape. A previous study indicated that younger nurses had a higher motivation to learn new skills and attended the continued education programs and this increased their perception of PSC.58 This was in line with a previous study carried out in the KSA, in which it was determined that nurses’ aged between 30 and 45 years old had higher scores of overall patient safety than those of more than 55 years.59 The results of the present study demonstrated that nurses’ working hours per week had no correlation with the overall perception of PSC among emergency nurses in Jordan. This might be due to the fact that nurses must work hard to accommodate the worldwide growing demands that overcome their limits, as identified by Fernandes et al.60 An illustration was obtained that the four hospitals required staffing and nursing services 360 days in year, 30 days a month, 7 days in week, and 24h/day.61 The findings from the current study showed no significant relationships were found between nurses’ experience in EDs and perceived PSC among emergency nurses in Jordan. These findings were supported by the previous studies; years of experience alone had no influential role of perceived PSC among nurses, and continued education with years of experience were linked together and associated positively with perceived PSC. This was in line with research that showed that overall perception of PSC was not correlated with the nurses’ experience despite the fact that most nurses had been in their work for at least 10 years.62 This can be explained by the fact that most nurses did not receive any programs for patient safety training, according to a study conducted by Abu-El-Noor et al.36

The current study has an specific limitation including the cross-sectional design that decreased the researcher's ability to detect a cause and cause-and-effect relationship between study variables. However, the presented associations of the study variables and overall perception of PSC were supported by an extensive literature review.

ConclusionPatient safety culture is one of the important issues for hospital management. Patient safety culture is an essential factor in the decreasing of medical errors and development of the institutions. Having lower rates of turnover intentions and an increase in reporting and the number of patient safety events were affected positively on overall perception of PSC. Based on the study results, managers should pay attention to increasing intent to stay among nurses and encourage them to document and communicate errors freely to improve the overall culture of patient safety. Finally, the integration of the regarding PSC concept among students.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the participants for their effort and time.