The executive functions (EFs) involve multiple subcomponents including inhibition, updating, and shifting. These subcomponents are mediated by distinct brain networks, each linked to specific neural oscillations. Frequency-specific stimulation is a key approach to achieving precise intervention on different cognitive functions through affecting specific spatiotemporal organizations of brain networks.

ObjectiveWe aimed to explore the modulation of different brain networks and EFs’ subcomponents by stimulation at frequencies of 0.02 Hz and 0.05 Hz, which are closely linked to whole-brain dynamics.

MethodIn a randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study, we applied anodal oscillatory transcranial direct current stimulation (O-tDCS) to the left DLPFC to investigate the frequency-specific modulation on oxy-hemoglobin (HbO) and offline EF scores (Experiment 1, N = 54), as well as online EF scores (Experiment 2, N = 48).

ResultNear the stimulation frequency, brain signals were significantly enhanced. Specifically, an increase in power at 0.02 Hz was associated with enhanced inhibitory function, while an increase in power at 0.05 Hz was linked to decreased updating function. Compared to the sham condition, 0.02 Hz stimulation increases PLV within the frontal lobe, whereas 0.05 Hz increases PLV between the frontal and parietal lobes, indicating the presence of distinct spatiotemporal structures within cognitive-related brain networks.

ConclusionThe frequency-specific modulation of O-tDCS on brain networks and EF subcomponents suggests that different EFs are supported by brain networks with specific spatiotemporal architectures, bolstering the spectral fingerprint hypothesis of cognition. The spatiotemporal structure of cognitive-specific brain networks offers novel insights and targets for non-invasive interventions targeting diverse cognitive functions.

Executive functions (EFs) are essential cognitive processes that govern an individual's thoughts and actions in goal-directed behavior (Friedman & Miyake, 2017). They comprise three key abilities (Lezak, 1982): (a) inhibition (or self-control), which involves controlling attention, behavior, thoughts, and emotions to override strong internal predispositions or external lures; (b) updating (or working memory), the ability to maintain and manipulate information mentally; and (c) shifting (or cognitive flexibility), the skill to shift perspectives or strategies when encountering new demands, rules, or priorities. Intact EFs enable individuals to maintain their goals and remain productive in varying environments. Conversely, their disruption can lead to executive disorders, a key factor in mental health morbidity and mortality (Dubreuil-Vall et al., 2019).

The neural substrate of EFs predominantly involves the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (De Boer et al., 2021; Takacs & Kassai, 2019), with the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) being frequently targeted for interventions (Baddeley & Wilson, 1988; Banich, 2009; Dubreuil-Vall et al., 2019; Duncan et al., 2000; Niendam et al., 2012; Strobach & Antonenko, 2017). The DLPFC plays a critical role in integrating information from various brain regions (Petrides & Petrides, 2005), while EFs exhibit hierarchical dynamics in which the DLPFC-mediated control mechanisms allocate cognitive resources for subsequent operations (Banich, 2009; Milham et al., 2003). According to the spectral fingerprints hypothesis, a brain region forms networks with different regions when performing various cognitive functions, with each circuit exhibiting oscillatory activity at specific frequencies (F. Lu et al., 2017; Siegel et al., 2012). In other words, cognitive specificity arises from the spatiotemporal structure, constituted by diverse networks and frequencies of neural oscillations (Wang et al., n.d.). Given the integrative nature of EFs, it necessitates spatiotemporal coordination of neural oscillations across multiple scales. As a hub region in EF-related networks, the DLPFC may orchestrate cross-frequency coupling, particularly by nesting higher frequencies within lower frequency bands (Yu et al., 2014). Therefore, non-invasive brain stimulation targeting the DLPFC within low frequencies holds potential to intervene in EFs.

Studies have explored the neuro-modulatory effects of slow oscillations on cognitive functions. For instance, 0.75 Hz electrical stimulation effectively facilitates slow-wave sleep enhancement (Marshall et al., 2006), whereas lower-frequency stimulation at 0.05 Hz shows specific efficacy in improving sustained attention performance (Qiao et al., 2022a). To achieve the enhancement of different EFs circuits, the frequency of stimulation holds the key. According to the dual-layer model of the global signal (GS), the GS coordinates various cognitive functions, including inhibition, based on the phase of physiological arousal (Zhang & Northoff, 2022), and this coordination is most active around 0.02 Hz (Gutierrez-Barragan et al., 2019). Furthermore, Age-related deterioration of updating function has been associated with progressive declines in spatiotemporal coordination dynamics between the task-positive network (TPN) and default mode network (DMN) (Grady et al., 2016). This pattern of inter-network coordination is characterized by pseudo-periodic BOLD signal amplitude oscillations, exhibiting a dominant frequency of approximately 0.05 Hz (Waqas Majeed et al., 2011). The existence of these discrete brain network patterns indicates that distinct infra-slow oscillations may specifically subserve different EFs (Engel et al., 2013; Palva & Palva, 2018; Buzsáki and Buzsáki, 2006; Connolly et al., 2016), aligning with the spectral fingerprints hypothesis (Lu et al., 2017). However, it remains unclear whether distinct infra-slow stimulations can modulate specific EFs.

Given GS-mediated inhibition function (Weinbach & Henik, 2013) and DMN-related updating impairments (Brown et al., 2019), we anticipated that both 0.02 Hz and 0.05 Hz brain stimulations could modulate EFs and exert a specific impact on different subcomponents. This study tested the hypothesis using a double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial, integrating behavioral assessments with functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS).

Materials and methodsParticipantsA total of 54 healthy undergraduates were recruited for Experiment 1, and 48 for Experiment 2, all from Sichuan Normal University, with no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders, normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and right-handed. They refrained from alcohol or caffeine intake 24 h before testing. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan Normal University (No. 2021LS003). Participants provided written informed consent and received monetary compensation.

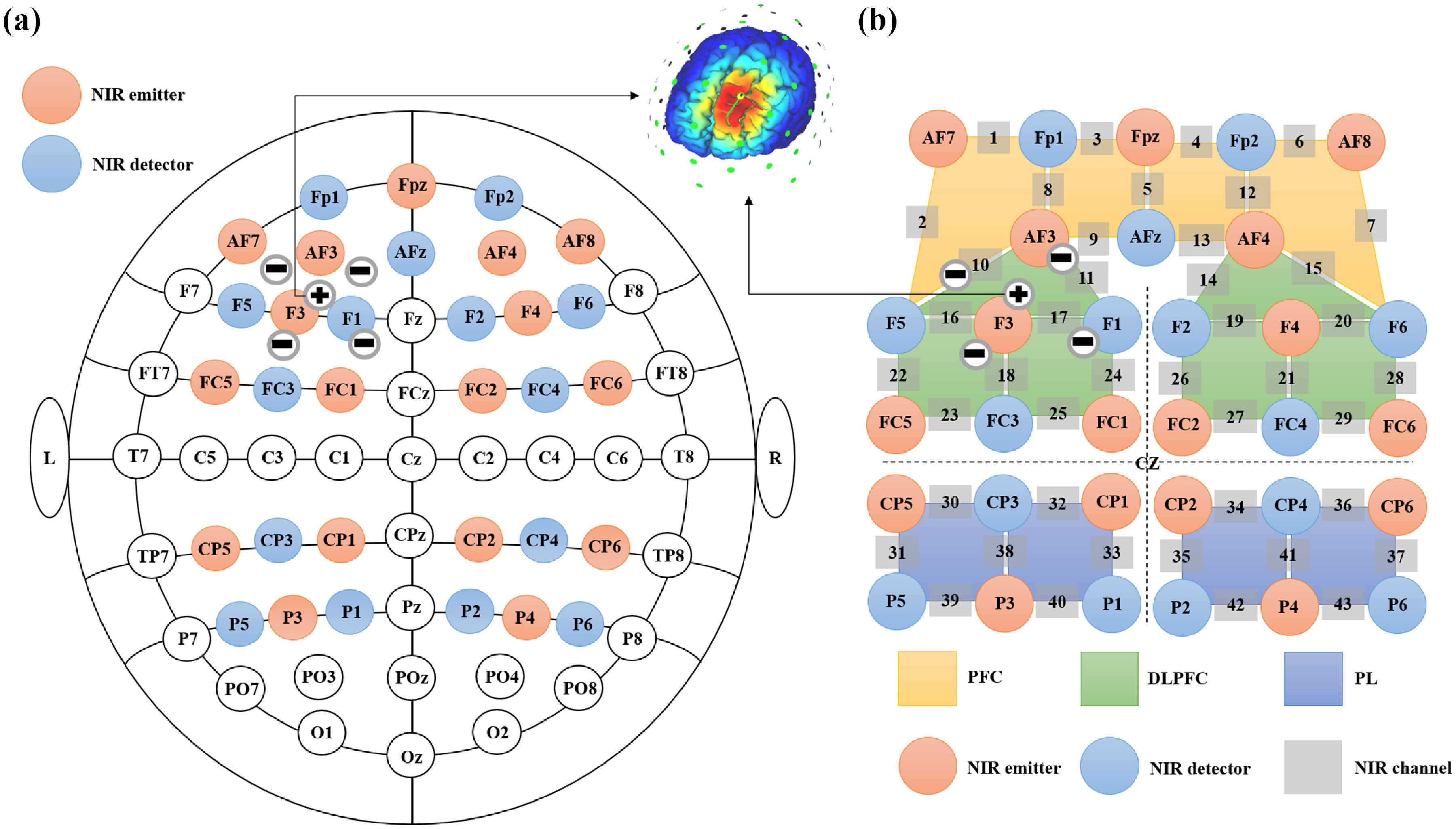

fNIRS imaging acquisition and preprocessingThe NirSmart-6000A (Huichuang, Danyang, China) was used in Experiment 1 for acquiring raw fNIRS data. This system comprises a near-infrared light source and avalanche photodiodes serving as detectors, operating at wavelengths of 730 nm and 850 nm, respectively, with a sampling rate of 11 Hz. The experimental setup incorporates 17 light sources and 15 detectors to form 32 effective channels. The average distance between the source and detector is 3 cm (ranging from 2.7 to 3.3 cm), conforming to the international 10/20 system for positioning (Fig. 1). Before the scan, the participant's head was fitted with a cap, and its alignment was verified. Subsequently, the subject's hair was adjusted to ensure unobstructed access to the scalp for the sources and detectors. Data collection via fNIRS commenced once all channels exhibited satisfactory data quality. The focal brain regions under investigation include the PFC, DLPFC, and parietal lobe (PL).

Concurrent setup of fNIRS light sources and detectors along with O-tDCS cathode-anode electrodes. (a) The 17 sources and 15 detectors covered the frontoparietal network, equivalent to 32 electrodes of the 10–20 EEG system. Five current electrodes were positioned near FC3 in a 4 × 1 electrode configuration for O-tDCS in the left DLPFC, with the middle electrode serving as the anode (+) and the remaining four as cathodes (-). (b) The detectors and light sources created 43 detection channels distributed across the PFC, DLPFC, and PL.

The fNIRS data preprocessing was conducted using the Homer3 software (Huppert et al., 2009). The procedure involved: (a) Identification of channels with poor signal quality using the coefficient of variation (CV) method, with the CV threshold of 7.5% (Almulla et al., 2022; Bonilauri et al., 2021; Hocke et al., 2018); (b) Conversion of raw light intensity data to optical density values; (c) Removal of motion artifacts through spline interpolation (Scholkmann et al., 2014; Brigadoi et al., 2014); (d) Conversion of optical density data to changes in oxy-hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxy-hemoglobin (HbR) concentrations based on the modified Beer-Lambert law (Baker et al., 2014). The HbO data were primarily used in subsequent analyses, due to their superior signal-to-noise ratio for reflecting changes in regional cerebral blood flow (Strangman et al., 2002; Hoshi & Y, 2016).

Transcranial direct current stimulation protocolThe O-tDCS shows promise in modulating EFs by affecting infra-slow rhythms (Bergmann et al., 2009; Marshall et al., 2006; Saebipour et al., 2015). We used a battery-operated tDCS equipment (NeuStim NSS14, Neuracle, Changzhou, China) for O-tDCS stimulation, which featured eight AgCl electrodes, with a 1 cm diameter. In a 4 × 1 electrode configuration, five electrodes were actively used, with the middle electrode serving as the anode and the remaining four as cathodes. This configuration was placed on the DLPFC, with the anodes approximately 2 cm away from each cathode (Fig. 1). Each 20-minute oscillatory stimulation comprised multiple cycles, each consisting of ramp-up, stimulation, and ramp-down phases. The sham condition involved 2-second stimuli only at the beginning and end, while all conditions maintained a current intensity ranging from 0 to 1 mA (see the Appendix Fig. A1).

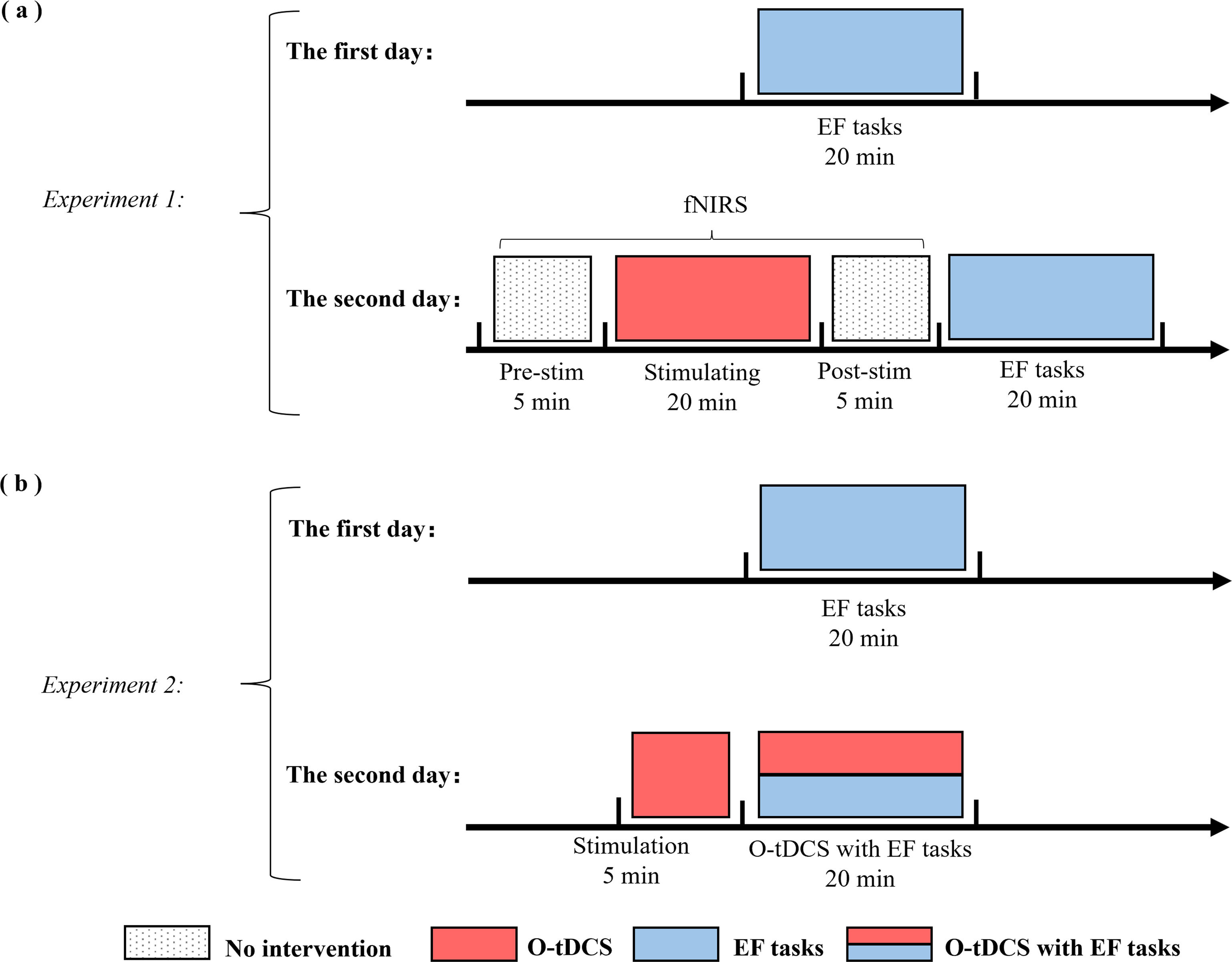

Protocol setupExperiment 1 explored the offline effects of infra-slow stimulation on EFs using three O-tDCS conditions: 0.05 Hz, 0.02 Hz, and sham stimulation (Fig. 2a). Each participant completed two sessions. The first session involved pre-evaluation of EFs. The second session had four phases: (a) a 5-minute pre-stimulation fNIRS, (b) a 20-minute synchronized fNIRS during O-tDCS, (c) a 5-minute post-stimulation fNIRS, and (d) post-stimulation evaluation of EFs. Additionally, participants completed a somatization perception questionnaire to test their feelings about O-tDCS and any associated side effects. Table A1 and Fig. A2 in the Appendix provide detailed information on the questionnaire and EFs measurements. The sequence of three tasks was randomized to mitigate potential practice and fatigue effects, with sessions spaced at least 24 h apart. Participants were blinded to the O-tDCS doses. Resting-state fNIRS data were collected with participants’ eyes open.

The experimental and stimulation procedure. (a) Experiment 1: Participants underwent baseline behavioral assessments of EFs on Day 1. On Day 2, the protocol began with a 5-minute resting-state fNIRS recording to establish neurophysiological baseline measures, followed by concurrent administration of 20-minute O-tDCS with continuous fNIRS monitoring. Post-stimulation procedures included a 5-minute fNIRS recording and behavioral reassessment of EFs. (b) Experiment 2: Baseline EFs measurements were collected on Day 1. Day 2 commenced with a 5-minute O-tDCS stabilization period, followed by an EFs task performance concurrent with O-tDCS.

Experiment 2 explored the online effects of different infra-slow stimulations on EFs. Each participant underwent two sessions (Fig. 2b), with the first session assessing their baseline EFs. In the second session, the left DLPFC received 5 min of anodal O-tDCS at either 0.02 Hz or 0.05 Hz, followed by three tasks during concurrent stimulation. The experimental group received 0.05 Hz or 0.02 Hz stimulation. Following stimulation, participants completed a somatization perception questionnaire. The session interval and task order were consistent with those of Experiment 1.

Statistical analysisSomatization perception of transcranial direct current stimulationExperiment 1 utilized a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to explore potential variations in participants' somatization perception across different stimulation conditions, while Experiment 2 employed an independent samples t-test for a similar analysis.

Behavioral dataError trials and extreme values exceeding the mean ± 3 standard deviations were removed before analyzing the effect of EFs to exclude potentially aberrant data. To account for variations in baseline cognitive levels among subjects, relative scores (expressed as proportional changes from baseline performance) were used to evaluate EF abilities: (a) Relative inhibition scores were calculated by dividing the difference between reaction times (RTs) in incongruent and congruent conditions by the RT in the congruent condition. (b) Relative updating scores were determined by dividing the difference between RTs in the 1-back and 0-back tasks by the RT in the 0-back task. (c) Relative switch cost was computed by dividing the difference between RTs in shift and repetition conditions by the RT in the repetition condition.

To evaluate the effects of different infra-slow stimulations on distinct EF subcomponents, we conducted a repeated measures ANOVA in Experiment 1 with three stim-type (0.02 Hz, 0.05 Hz, and sham) and two stim-state (pre-stimulation and post-stimulation). In Experiment 2, we performed a repeated measures ANOVA with two stim-type (0.02 Hz and 0.05 Hz) and two stim-state (pre-stimulation and stimulating) to compare EFs scores. Post-hoc t-tests were conducted following significant interactions, with Bonferroni’s correction applied for multiple comparisons (Chen et al., 2008; Friedman et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2021).

fNIRS dataTo assess the stimulatory effects, paired sample t-tests were conducted on HbO changes between pre-stimulation and stimulation periods. Baseline correction was performed by subtracting the 5-min pre-stimulation resting-state signal mean from task-period data, following standard fNIRS research practices for hemodynamic response normalization (Tak & Ye, 2014). This standard procedure enhances stimulus-evoked response detection by controlling for interindividual variability in resting hemodynamics. Channels exhibiting a positive effect underwent further analysis of average HbR and HbO changes between pre-stimulation and stimulation to differentiate stimulation-induced HbO changes from physiological errors like vasoconstriction. Channels showing significant positive effects were then selected for investigating local neurophysiological changes from stimulation.

Local discrepancies in peak power surrounding target frequency points (±0.002 Hz) were analyzed to investigate the impact of O-tDCS on neural oscillations using power spectral density (PSD) analysis (Welch, 1967). Data processing was standardized by focusing on the initial five minutes’ post-stimulation onset, consistent with the pre-stimulation period. Due to the dynamic nature of the variable being modulated across participants, baseline states are expected to vary significantly (Nazbanou et al., 2014). Paired sample t-tests were utilized to compare power differences between pre-stimulation and stimulation periods, rather than comparing sham and oscillatory stimulation conditions. Additionally, the brain-behavior relationship was assessed by correlating peak power at the corresponding frequency with performance on various EFs using Pearson correlation analysis.

Phase locking values (PLV), a measure of phase synchronization between neural signals, were analyzed globally across all 43 channels for six stimulation phases. PLV represents the phase covariance between two signals in the same time window and is more sensitive to phase coupling than traditional correlation-based functional connectivity (Lachaux et al., 1999). A repeated measures ANOVA with factors of stim-type (0.05 Hz vs. sham, 0.02 Hz vs. sham) and stim-state (pre-stimulation, four stages of stimulation each lasting five minutes, post-stimulation) was conducted to compare PLV dynamics between stimulation conditions and sham at specific frequencies (±0.002 Hz), and the assumption of sphericity was verified using Mauchly's test. In cases where sphericity was violated (p < 0.05), Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied to adjust the degrees of freedom accordingly (Greenhouse & Geisser, 1959). Post-hoc t-tests were conducted on channel pairs showing significant interaction effects, with Bonferroni correction applied for multiple comparisons (Chen et al., 2008; Friedman et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2021).

ResultSafety and tolerability of transcranial direct current stimulationData from all conditions are summarized in Appendix Table A2. The only adverse effects observed across the three stimulation conditions were fatigue, pricking sensation, and headache (mean score >2). There was no statistically significant difference in side effects in between-group comparisons (stim-type).

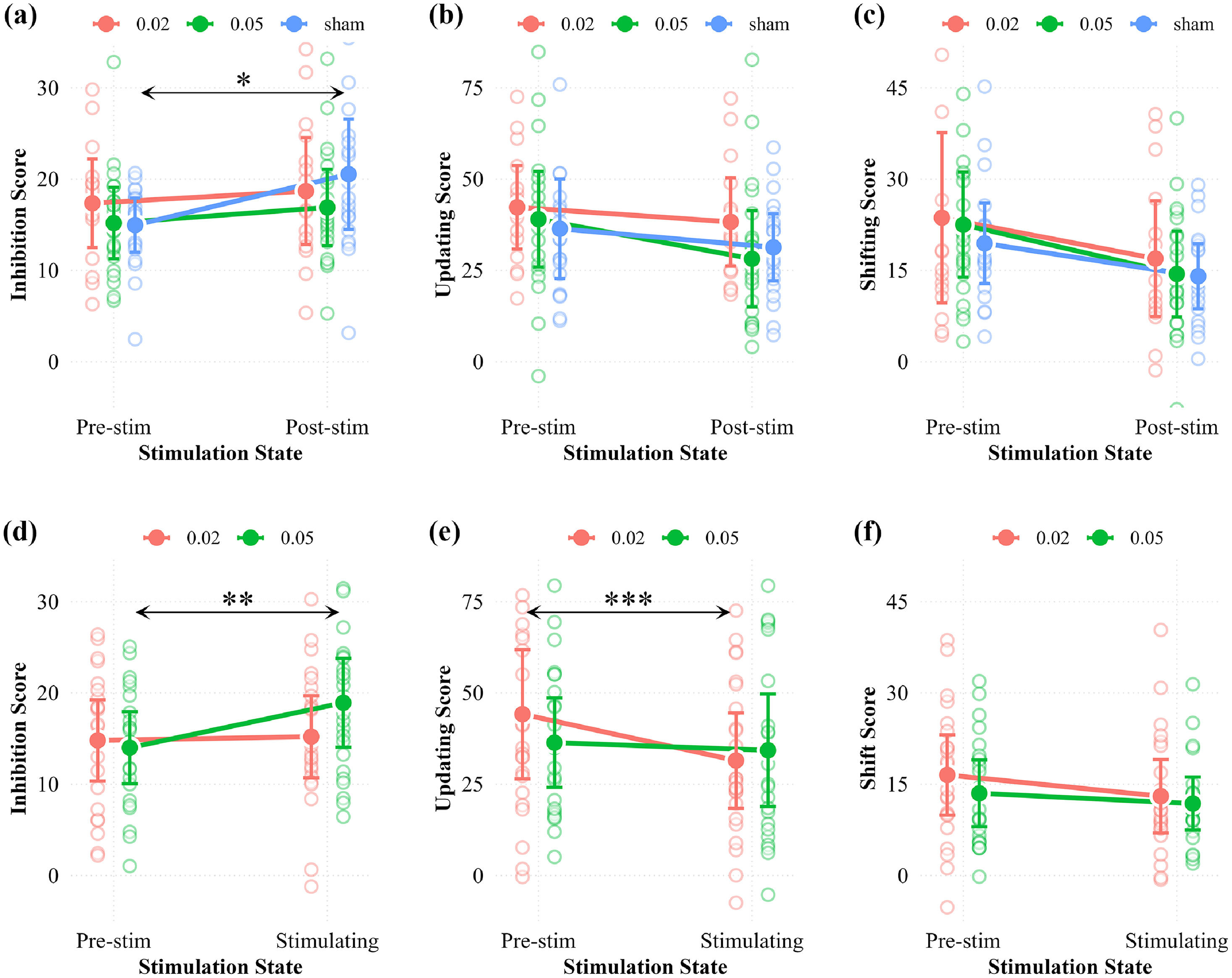

Behavioral resultsOffline effects: infra-slow stimulation improves the efficiency of inhibitionExperiment 1 shows the offline effect of different infra-slow stimulations. A marginally significant main effect of stim-state is observed across all tasks, along with a notable interaction between stim-state and stim-type on inhibition score, showing a medium-to-large effect size (p = 0.052, η²p = 0.11, Appendix Table A3). Specifically, post-hoc analysis indicates a significantly higher inhibition score following sham stimulation (pbonferroni = 0.044, Appendix Table A4), whereas stimulation conditions did not show such impairment (Fig. 3a). Additionally, the lack of a significant interaction in updating and shifting function suggests that the changes in these EF subcomponents from pre- to post-stimulation are not significantly different based on the differing stimulation types employed (Fig. 3b-c).

Behavioral results from Experiment 1 (a-c) showing changes in different EFs scores between pre- and post-stimulation assessments across different stimulation conditions: (a) Inhibition; (b) Updating; (c) Shifting. Corresponding results from Experiment 2 (d-f) demonstrate different EFs scores changes between pre-stimulation and during stimulation across conditions: (d) Inhibition; (e) Updating; (f) Shifting. Error bars represent standard errors. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Bonferroni-corrected).

Experiment 2 shows the online effect of different infra-slow stimulations. A main effect of stim-state was consistently observed across all tasks. Then, a significant interaction was found between stim-type and stim-state on inhibition and updating scores, with a medium-to-large effect size (inhibition: p = 0.035, η²p = 0.093; updating: p = 0.035, η²p = 0.093, Appendix Table A3). Specifically, post-hoc analysis revealed that inhibition scores increased under the 0.05 Hz stimulation (pbonferroni = 0.01, Appendix Table A4) and remained relatively stable under the 0.02 Hz stimulation. Moreover, the decline in updating scores under the 0.02 Hz stimulation (pbonferroni = 0.004, Appendix Table A4) was significantly more pronounced compared to the 0.05 Hz stimulation. For the shifting function, no significant interaction was detected (Fig. 3d-e). Although an uncorrected marginal effect emerged in switch costs during 0.02 Hz stimulation (pre-stim vs. stimulation, p = 0.062), it did not survive correction (pbonferroni = 0.37).

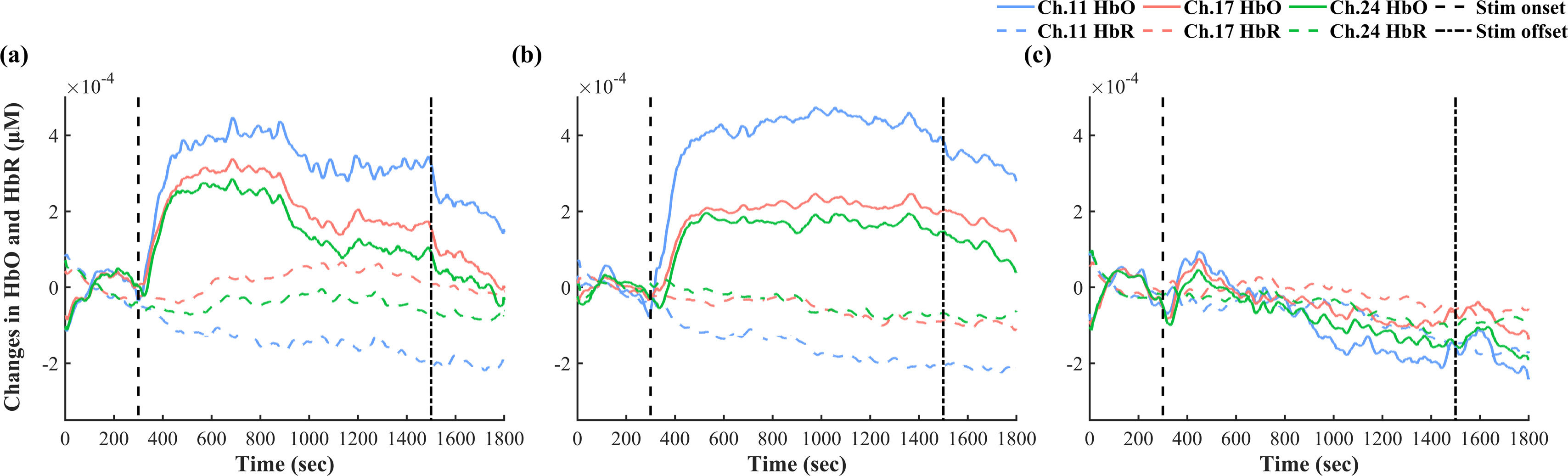

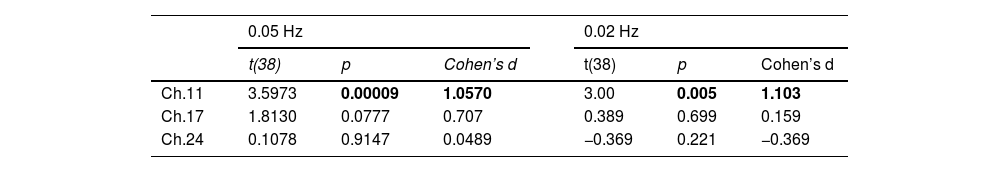

The fNIRS resultsAverage hemodynamic changes: O-tDCS increases HbO without affecting HbR around stimulation sitePaired sample t-tests on HbO before and after O-tDCS revealed significant increases in three channels (Channel 11: p < 0.001, η²p = 1.09; Channel 17: p < 0.01, η²p = 0.64; Channel 24: p < 0.05, η²p = 0.48, Appendix Table A5), localized to the left DLPFC. Subsequent analysis of O-tDCS effects revealed distinct trends between ΔHbO and ΔHbR. Specifically, ΔHbO exhibited a sustained increase during stimulation, followed by a post-stimulation decline, while ΔHbR showed a mild decrease (Fig. 4). These channels were identified as the main stimulation sites for subsequent analyses.

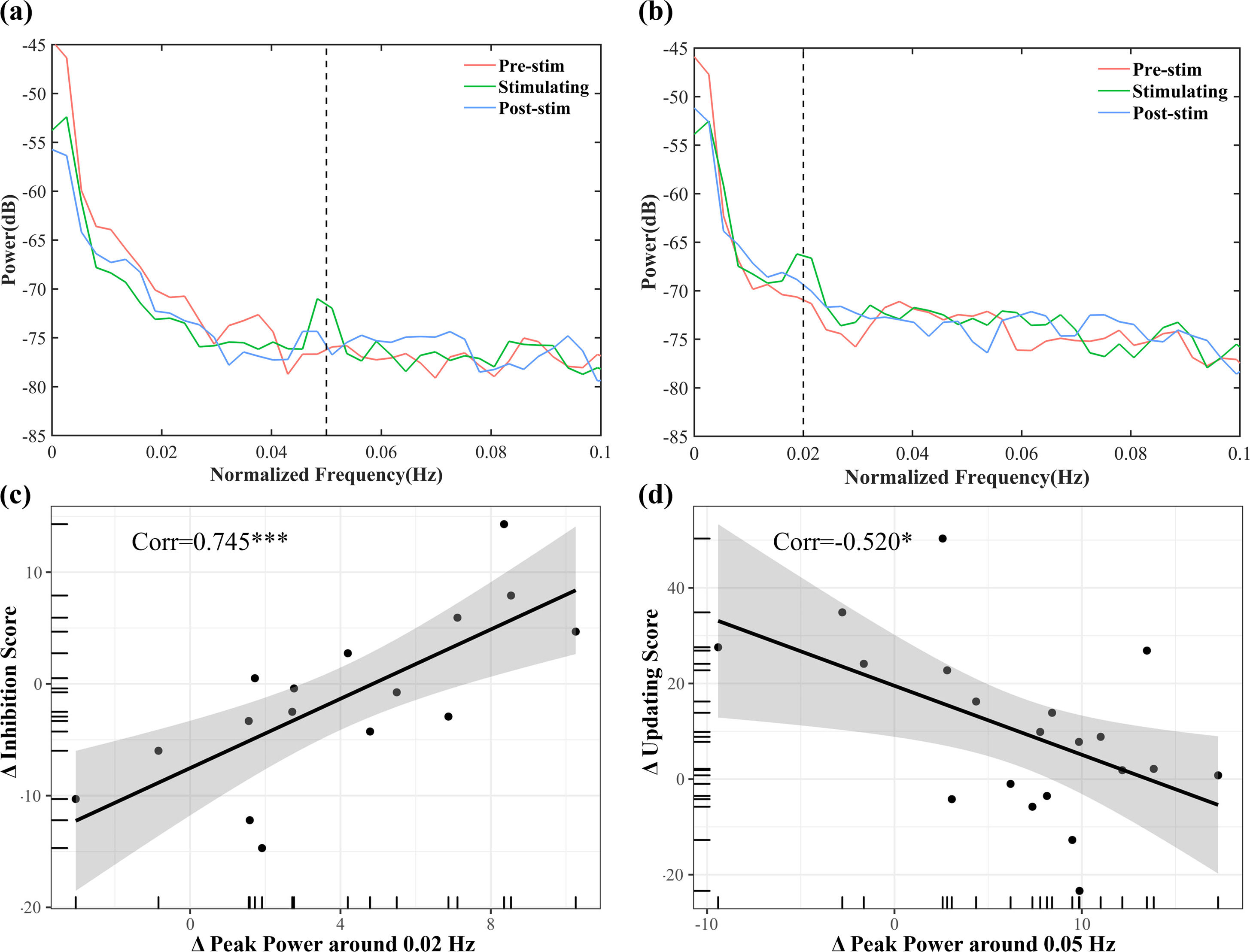

Local effect: Behaviorally relevant power increase at the stimulation frequency of infra-slow O-tDCSPaired-sample t-tests revealed a significant increase in peak power within frequency bands near the stimulation frequencies following O-tDCS in both the 0.05 Hz (p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.057) and 0.02 Hz (p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 1.103; Fig. 5a-b, Table 1) stimulation groups. A correlation analysis showed a significant positive correlation between increased power around 0.02 Hz and decreased inhibition scores in the 0.02 Hz group, while a negative relationship was observed between increased power around 0.05 Hz and decreased updating scores in the 0.05 Hz group. These findings offer insights into the mechanisms of different infra-slow stimulation on EFs (Fig. 5c-d).

Results of PSD analysis and its correlations with EFs. Changes in peak power at 0.05 Hz (a) and 0.02 Hz (b) pre- and post-stimulation. Significant correlations between power increase and EFs score changes: (c) A positive correlation between 0.02 Hz power and inhibition score changes indicate that higher 0.02 Hz power leads to greater decreases in inhibition scores, while (d) a negative correlation between 0.05 Hz power and updating score changes suggest that higher 0.05 Hz power results in smaller decreases in updating scores. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

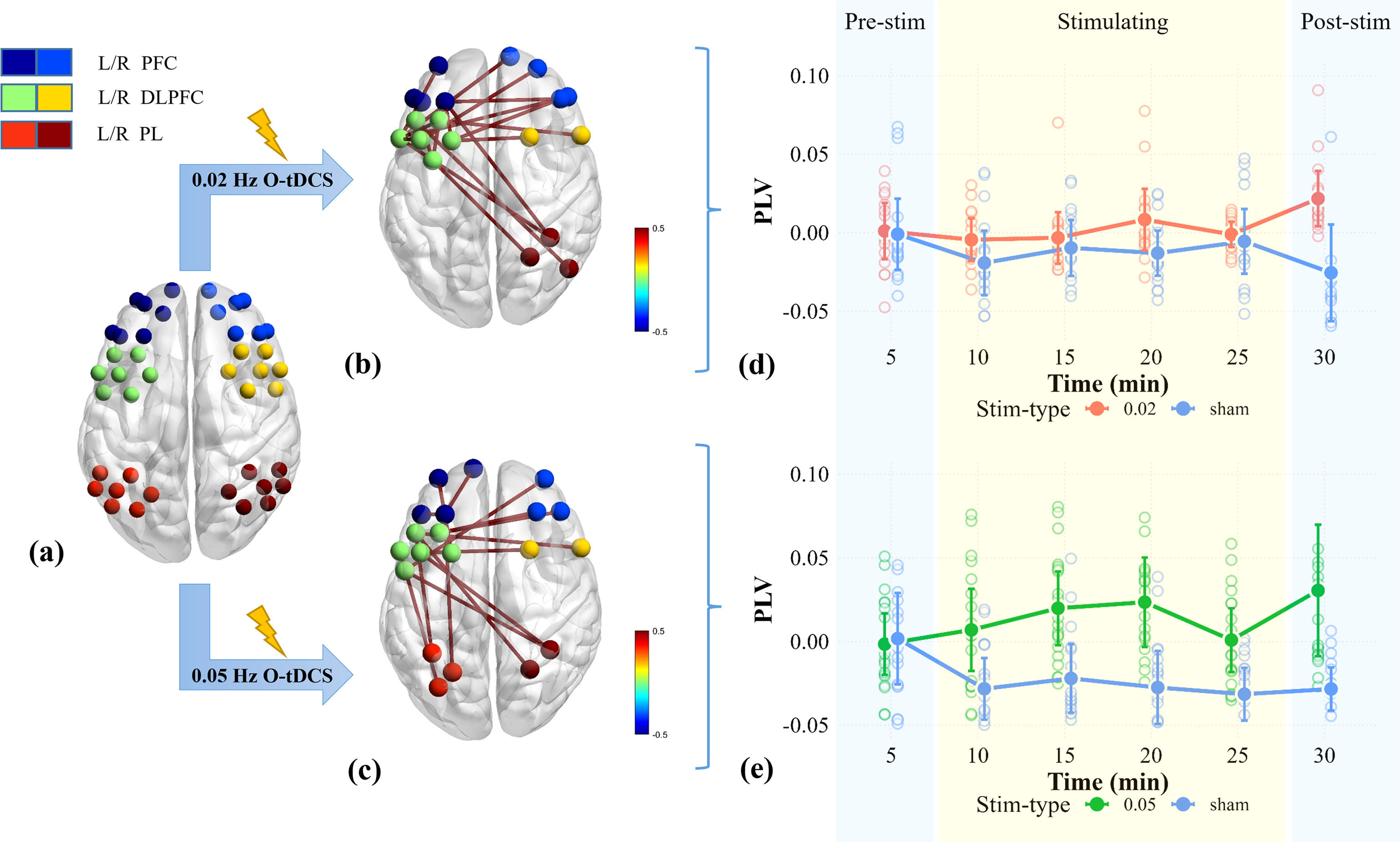

Compared to sham stimulation, significant interactions for PLV changes primarily emerged between the DLPFC and PFC at 0.02 Hz, with limited extension to contralateral PL regions (p = 0.007, η²p = 0.111, Appendix Table A8). In contrast, significant interactions at 0.05 Hz exhibited broader spatial distribution, involving both DLPFC-PFC and bilateral PL connections (p < 0.001, η²p = 0.121, Appendix Table A8). Post-hoc analyses demonstrated a significant increase in mean PLV during stimulation at both frequency conditions (compared to the pre-stimulation baseline), while the sham condition failed to induce similar modifications (Fig. 6). Detailed results of the post-hoc t-tests are presented in Appendix Table A6–9.

Result from PLV analysis. (a) Schematic representation of fNIRS channels. (b-c) PLV connections exhibiting significant interaction effects between stim-type and stim-state across spatial scales (p < 0.05): (b) 0.02 Hz vs. sham control, (c) 0.05 Hz vs. sham control. (d-e) The mean temporal dynamics of significant PLV between stim-type and stim-state:(d) 0.02 Hz vs. sham control, (e) 0.05 Hz vs. sham control.

This study represents the first systematic investigation into the effects of infra-slow O-tDCS on EFs. Our behavioral results demonstrate that infra-slow O-tDCS modulates EFs in a frequency-specific manner. Offline assessments revealed a stronger stability (without time-dependent decline) in inhibition function following infra-slow stimulation, while online assessments showed better performance on both inhibition and updating functions during stimulation of 0.02 Hz. The discrepancy in updating function between offline (Experiment 1) and online (Experiment 2) sessions may stem from the temporal dynamics of modulation. The observed efficacy variations across EF subcomponents could be due to differences in stimulated networks or energy requirements for engaging distinct brain circuits. The absence of an interaction effect on the shifting function may suggest its oscillations operate beyond the 0.02–0.05 Hz range. These findings support the spectral fingerprints hypothesis, indicating that unique spatiotemporal oscillatory architectures underlie specific cognitive subcomponents. Further clarification of infra-slow O-tDCS effects requires synchronous multimodal neural signal recordings in addition to behavioral assessments (Thut et al., 2017; Salehinejad et al., 2022).

Cortical neurotransmitters and enhanced neuronal activity can influence hemodynamics (Stagg et al., 2009; Stagg & Nitsche, 2011), and FNIRS can non-invasively measure the changes in state-related concentrations of HbO and HbR. We observed significant HbO changes in many regions during stimulation, with channels near the anode showing positive activation and distant channels displaying negative activation. Opposing HbO and HbR trends observed in these positively activated channels exclude vascular constriction as a confounding factor in oxygen dynamics. Notably, near the left DLPFC, both the 0.05 Hz and 0.02 Hz groups exhibited higher power peaks near their respective stimulation frequencies than pre-stimulation. These findings indicate the brain's ability to respond and adapt to different infra-slow stimulation frequencies, aligning with previous studies on task-periodicity (Fiveash et al., 2020; Klar et al., 2022, 2023). These results support the entrainment theory (Thut et al., 2011, 2012), suggesting that regularly repeated external stimulation can entrain brain activity (Thut et al., 2012).

Changes of neural oscillations have been shown to modulate cognitive efficiency (Garrett et al., 2013, 2014; Thut et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2017; McDonnell & Ward, 2011; Palva & Palva, 2018). This study further examined the role of enhanced infra-slow power in EFs, suggesting that the 0.02 Hz-related effectiveness in inhibition and updating may be mediated by separate neural mechanisms. Specifically, increased 0.02 Hz activity near the stimulation site facilitated inhibition function, while elevated 0.05 Hz activity constrained updating function. These trends were consistent in Experiment 2, suggesting that different EF subcomponents may be regulated by distinct infra-slow oscillations.

Brain oscillations in different frequencies are believed to facilitate information exchange within and between different brain regions (Begleiter et al., 2006; Klimesch et al., 1996). To explore the mechanisms underlying this modulation, we analyzed the spatial characteristics of this effect by examining changes in PLV across all channels within the frequency range surrounding the stimulation frequency (±0.002 Hz). We observed significant interactions predominantly localized between the left DLPFC and PFC, with a little extension to contralateral parietal regions at the frequency of 0.02±0.002 Hz. Intriguingly, as the frequency range shifted to 0.05±0.002 Hz, the interaction transitioned from the original DLPFC-PFC circuitry to connections between the bilaterally PL and the left DLPFC. Specifically, we observed an increase in PLV following the onset of stimulation, a pattern not evident in the pseudo-stimulus condition, consistent with prior tDCS studies (Veniero et al., 2015). Increased PLV suggests enhanced neural synchrony (Fiori et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2022), demonstrating specific region-plasticity under various infra-slow stimulation. These findings also align with distinct changes in EFs: the PFC, known for its role in inhibition functions (Aron et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2001), exhibited significantly increased local phase synchronization between the left DLPFC and PFC at 0.02 Hz (Fig. 6b). This heightened local synchrony in the PFC likely facilitated the suppression of irrelevant distractions, thereby strengthening the inhibition function (Aron et al., 2014). Furthermore, stimulation at 0.05 Hz augmented long-range coupling between the DLPFC and PL (Fig. 6c), a network crucial for stimulus-driven memory functions (Anticevic et al., 2010), with its activity suppression associated with increased memory load (Todd et al., 2005). The enhanced synchrony after stimulation may increase information exchange with other regions while reducing memory load.

Different oscillation frequencies are associated with various levels of neural information processing (Chase et al., 2020; Jensen & Colgin, 2007; Wang et al., 2016, 2018, 2019). High-frequency oscillations are linked to local neural activity, while low-frequency oscillations regulate long-distance information transmission and integration (Salvador et al., 2005). This scale effect is not limited to physical distance but is also tied to the functional characteristics of specific brain regions and the complexity of cognitive tasks. Regions with higher cognitive functions exhibit lower activity frequencies (Murray et al., 2014). Infra-slow oscillations can enhance the integration and transmission efficiency of neural information by coordinating different functional networks (Watson & Watson, 2018). Our study observed that different infra-slow O-tDCS might have distinct effects on various EF subcomponents. These findings suggest that distinct infra-slow oscillations may coordinate various brain networks across different scales, influencing specific cognitive functions.

O-tDCS at different infra-slow frequencies holds great potential for targeted EFs intervention. The enhancement of inhibition during 0.02 Hz stimulation may benefit individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, where inhibition deficits are significant. Similarly, the impact of 0.05 Hz stimulation on updating function could be valuable for addressing cognitive decline in older adults, who often experience working memory impairments. However, translating these findings to clinical or educational settings poses challenges (Qiao et al., 2022b). Longitudinal studies are necessary to determine if short-term effects lead to lasting cognitive enhancements. Additionally, the variability in neural oscillatory patterns across cognitive functions and individuals complicates standardized application. Understanding the frequency-dependent characteristics of cognitive functions is crucial for optimizing intervention effects by aligning with individuals' neural oscillations.

LimitationSeveral limitations should be noted regarding our results. Firstly, in investigating the effects of tDCS on EFs, researchers often consider the lateral regions of the PFC, which coordinate various neural networks for EFs (Baddeley & Wilson, 1988; Banich, 2009; Duncan et al., 2000; Niendam et al., 2012). However, it is crucial to recognize that EFs, with their diverse components, entail the synchronized activity of multiple brain regions rather than the isolated function of a single region. Although our study contributed to understanding the neural mechanisms of EFs, the spatial constraint is notable, as we concentrated solely on the left DLPFC. Besides, while fNIRS holds high temporal resolution and portability, enabling real-time synchronization of stimulation and behavioral assessments, it is inherently limited in detecting deep brain regions. Future studies should employ multimodal neuroimaging to delve into the interactions among multiple brain regions to gain a more comprehensive insight into the neural basis of EFs. Secondly, the modest sample size in our study may introduce sampling bias and potential issues such as overestimation of statistical power associated with small samples (Indahlastari et al., 2021; Horvath et al., 2015). While our effect sizes are acceptable, replication in larger cohorts is imperative to enhance the generalizability and validate the robustness of our findings. Thirdly, our study population was predominantly composed of university students. It may limit the generalizability of findings to broader populations with varying age ranges, educational backgrounds, and cognitive profiles. Fourthly, the lack of longitudinal data precludes conclusions about the lasting impact of the intervention. Transient modulation effects may not lead to enduring behavioral changes, and neural plasticity mechanisms require prolonged observation periods to manifest. Longitudinal designs tracking both neural and behavioral outcomes with repeated stimulations may clarify whether repeated O-tDCS yields cumulative benefits or compensatory adaptations, thereby informing a reasonable intervention protocol.

ConclusionThis study provides preliminary evidence suggesting the potential efficacy of infra-slow O-tDCS on the left DLPFC in modulating neural activity and enhancing EFs. The frequency-specific effects of O-tDCS on EF subcomponents and brain networks reveal the intricate spatiotemporal networks that underlie EFs. This underscores the necessity of taking into account cognitive-specific frequency and target locations when formulating intervention strategies. The infra-slow stimulation and its spatiotemporal mechanisms warrant further investigations and applications.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62177035, 32471101), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2024NSFSC2086) and BRKOT-SICNU (20210628W).