Antihypertensive medication non-adherence is an important cause of poor control in hypertension. The role of motivational interventions to increase antihypertensive medication adherence remains unclear.

ObjectiveTo systematically review RCTs of motivational interventions for improving medication adherence in hypertension.

MethodsEMBASE and Pubmed were searched from inception to February 2019 for RCTs of motivational interventions for improving medication adherence in hypertension vs. usual care. Inclusion criteria: RCTs with motivational intervention to improve medication adherence in adults with hypertension. A blinded review was conducted by 2 reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by consensus/a third reviewer.

Data extraction and quality appraisal was performed using the risk of bias tool from cochrane collaboration. The meta-analyses of blood pressure control used random-effects models to report mean difference and 95% CIs. Primary outcome was medication adherence and second outcome was blood pressure control.

ResultsThe search methodology yielded 10 studies comprising 1171 participants. Medication adherence improved significantly in 5 studies. We could not perform pool analysis for this outcome due to different measurements of medication adherence. Seven trials reported significant results regarding blood pressure control.

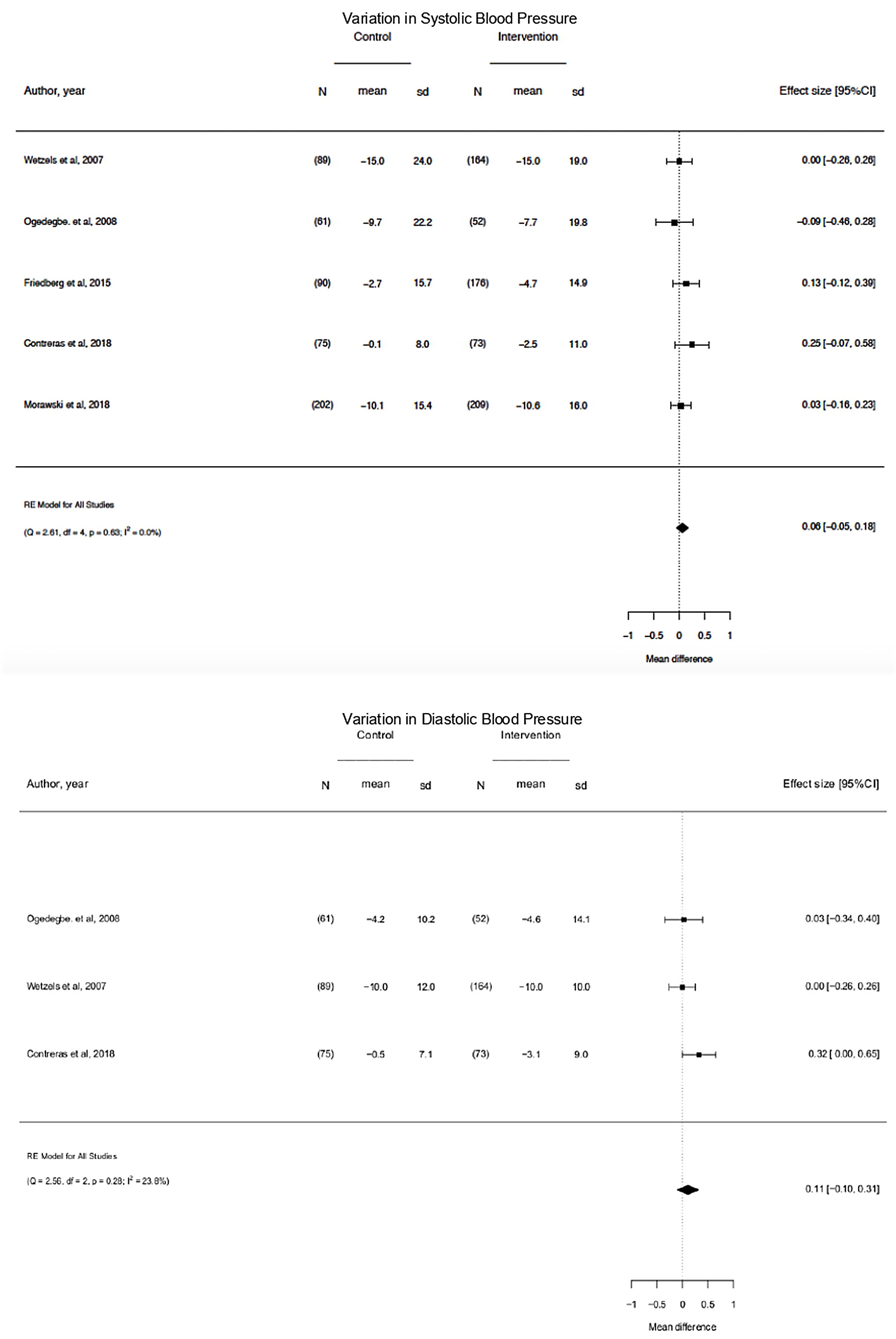

On pooled analysis, motivational interventions were not significantly associated with a systolic blood pressure (mean difference, −0.06; 95% CI, −0.05 to 0.18; p=0.63; I2=0.0%) or diastolic blood pressure (mean difference, −0.11; 95% CI, −0.10 to 0.31; p=0.28; I2=23.8%) decrease or blood pressure control.

ConclusionsMotivational interventions seem to significantly improve medication adherence but not significantly blood pressure control in hypertension, although evidence is still being based on few studies, with unclear risk of bias.

La falta de adherencia a la terapia farmacológica es una de las principales razones del descontrol de la hipertensión arterial. Se desconoce el papel de las intervenciones motivacionales en el aumento de la adherencia.

ObjetivoRealizar una revisión sistemática de ensayos clínicos aleatorizados (ECA) dirigidos a mejorar la adherencia a la medicación en hipertensión arterial.

MétodosSe buscaron ECA de intervenciones motivacionales vs. atención habitual en las bases de datos Embase y PubMed desde su inicio hasta febrero de 2019. Criterios de inclusión: ECA de intervenciones motivacionales para aumentar la adherencia a la terapia con medicamentos en adultos con hipertensión. Dos revisores realizaron una revisión ciega y sus desacuerdos se resolvieron por consenso/por un tercer revisor.

La extracción de datos y la evaluación de la calidad se realizaron mediante la herramienta Cochrane de evaluación del riesgo de sesgo. El metaanálisis del control de la presión arterial utilizó modelos de efectos aleatorios para informar la diferencia en las medias y los intervalos de confianza de 95% (IC 95%). El outcome primario fue la adherencia a la medicación y el secundario fue el control de la presión arterial.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 10 estudios con 1.171 participantes. La adherencia mejoró significativamente en cinco estudios. No fue posible realizar un análisis agrupado de la adherencia debido al uso de diferentes medidas de cumplimiento. Siete estudios mostraron una diferencia significativa en el control de la presión arterial.

En el análisis conjunto, las intervenciones motivacionales no se asociaron a una disminución significativa de la presión arterial sistólica (diferencia de medias, -0,06; IC 95%, -0,05-0,18; p=0,63; I2=0%) o de la presión arterial diastólica (diferencia de medias, -0,11; IC 95%, -0,10-0,31; p=0,28; I2=23,8%) o a mejora en control de la misma.

ConclusionesLas intervenciones motivacionales parecen mejorar significativamente la adherencia en lugar del control de la presión arterial en la hipertensión. Sin embargo, la evidencia aún se basa en pocos estudios, con un riesgo de sesgo incierto.

Arterial hypertension (HTN) is a global public health issue,1–5 remaining the major preventable cause of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and all-cause death globally.6–9

HTN is defined as office systolic blood pressure (SBP) values ≥140mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) values ≥90mmHg10,11 and it is a major risk factor for CVD such as stroke,12,13 heart failure,14 atrial fibrillation, peripheral vascular disease, vision loss, chronic kidney disease and dementia.15–18

Lowering blood pressure (BP) can substantially reduce morbidity19 and mortality.10 Despite this, BP control rates remain poor worldwide.10,18,20 Therapeutic nonadherence is thought to account for nearly half of poorly controlled hypertension result.21–24

The World Health Organization suggested that “increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions might have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments”.25

Multiple types of interventions to improve adherence to antihypertensive medication have been studied but it is unclear which interventions are most effective.26–28

Motivational or behavioural29 interventions are those such as compliance dispensers, drug reminder charts, teaching self-measurement and the record of the blood pressure, monthly home visits, phone calls by health providers, social support, small group training, postal reminders, telephone-linked computer counseling, among others. This type of interventions may have a great impact on medication compliance, as the patient may feel better understood supported and might acknowledge his problem of control of HTN.30,31

Motivational and more complex interventions were considered promising, although there is insufficient evidence.26,32–34 The most promising intervention components are those linking HTN adherence behaviors with habits, providing adherence feedback, self-monitoring of BP and motivational interviewing but further studies should be conducted.32

This systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized control trials (RCT) was conducted to answer the question: “Are motivational interventions more effective than standard care in improving medication adherence and BP Control in adults with HTN?”.

MethodsWe followed the statement on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for RCTs35 and registered our review in Prospero (PROSPERO Identifier: CRD42018100098).

Data sources and searchesFor this systematic review and meta-analysis, PubMed and EMBASE databases were searched from inception to February 2019 for RCT of motivational interventions for improving medication adherence in HTN vs. usual or standard care by using the following search strategy for Pubmed (“Hypertension/drug therapy” [MAJR]) AND “Medication Adherence” [MAJR] OR (“Hypertension/psychology” [MAJR]) AND “Medication Adherence” [MAJR]; and for Embase, the search strategy was: Hypertension AND (Medication OR Motivational OR Psychology).

No filter restrictions were applied in the databases search. Authors of relevant papers were contacted regarding further published and unpublished data. No language restrictions were imposed for the search which was limited to humans. The present systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted and reported according to the recommendations of The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA).35

The meta-analyses of blood pressure decrease and control used random-effects models to report mean difference (MDs) and 95% CIs.

Eligibility criteriaIn the present review, we included RCTs and quasi-RCTs with motivational intervention and medication adherence as a measured outcome; enrolled participants were adults (age above ≥18 years old) with primary HTN, already on at least 1 medication in the beginning of the study, regardless of race, ethnicity or comorbidities, and randomized to motivational interventions or Usual care. Motivational interventions were those aiming to improve AHM adherence in patients with HTN such as compliance dispensers, drug reminder charts, self-recording of blood pressure, monthly home visits or phone calls by health providers, social support, small group training postal reminders, telephone-linked computer counseling, among others. Control group was Usual care in hypertension management; usual or standard care refers to minimal or no motivational interventions being implemented; Adherence to medication was the primary outcome and BP control was the secondary outcome. Studies enrolling hospitalized participants were excluded.

Study selectionData and records management throughout the review were conducted in Covidence.36

Two reviewers (C.O. and B.S.) independently screened titles, abstracts and full-text articles reporting potentially eligible studies.

Divergent opinions regarding study inclusion were settled by discussion and consensus; if consensus was not obtained, a third author was called to settle the dispute.

Data extractionData extraction from selected studies was performed and presented in tables. Items reported on the data extraction form for each eligible study included: last author's name, publication year, study design, number of participants, gender, age, inclusion criteria, intervention, and control strategies, relevant outcome measures and respective results such as mean scores in the chosen scale, report mean difference (MDs) between pre-and post-intervention intention or calculated Odds risks (RRs) and 95%CIs and information about the variables used in the analysis.

The primary outcome assessed was medication adherence, which was measured through subjective and objective measures. Subjective measures included self-report tools such as the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) or other validated scales or definition of adherence and noting how this was defined and measured in each study. Objective measures refer to pill count or medication electronic monitoring systems (MEMS).

The secondary outcome was BP control. This outcome can help examine the relationship between interventions, therapeutic adherence and blood pressure control. BP change in mmHg or change in BP control according to the criteria used in each RCT was considered. A reduction of blood pressure refers to the difference between the changes of blood pressure between baseline and follow-up in the intervention and control groups.

Outcomes were described narratively.

Quality assessmentStudy quality was assessed by the two reviewers (C.O. and B.S.) using the risk of bias tool provided by the Cochrane Collaboration37; the overall level of bias risk for each study was then classified as low (all key domains presenting low risk), unclear (one or more key domains with unclear risk; usually due to lack of information to make a clear judgment), and high (high risk for one or more key domains). Sequence generation and blinding of outcome assessors were the key items in the deliberation about the low, high or unclear overall risk of bias of each included study. Disagreements were resolved by the two main reviewers by consensus and a third reviewer was consulted if necessary.

Statistical analysisResults with a p value <0.05 were considered statistically significant across studies included.

Pooled association of medication adherence could not be performed due to high heterogeneity as medication adherence was measured in different ways.

For the meta-analysis of BP control, only MDs and 95% CIs reported by individual studies were used. Because of known clinical and methodologic heterogeneity of studies, effect estimates were pooled using random-effects models. We calculated a summary measure of the difference in blood pressure variation measured in the two groups and evaluated the heterogeneity through Q test and I2 statistics. The I2 is the proportion of total variation observed among the studies that is attributable to differences between studies rather than sampling error (chance), with I2 values corresponding to the following levels of heterogeneity: low (<25%), moderate (25%–75%), and high (>75%).37

The summary measure was translated into two forest plots: one for systolic blood pressure and another for diastolic blood pressure and one for percentage of controlled BP.

We performed the meta-analysis using R software package metafor (v 3.3.2).

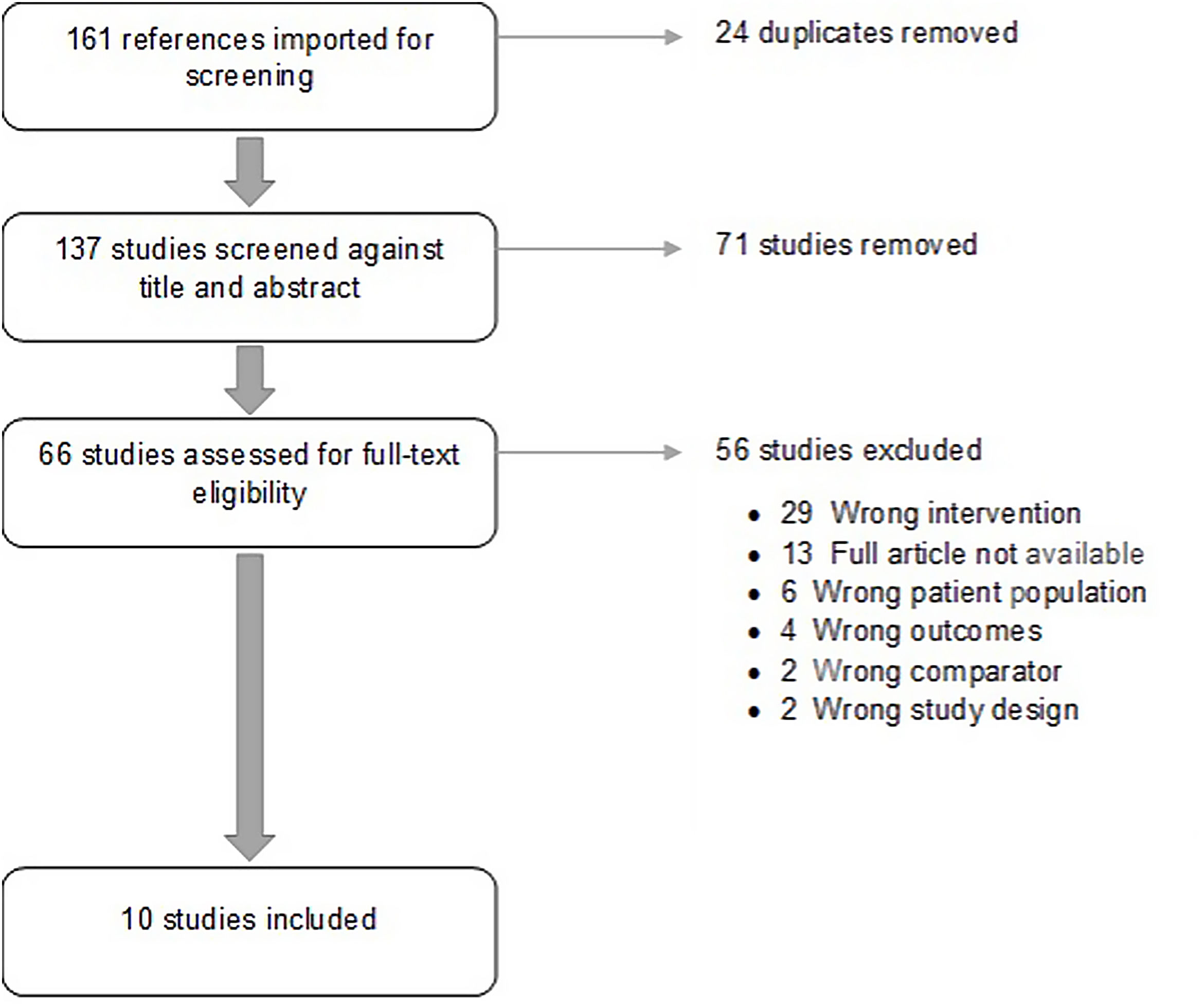

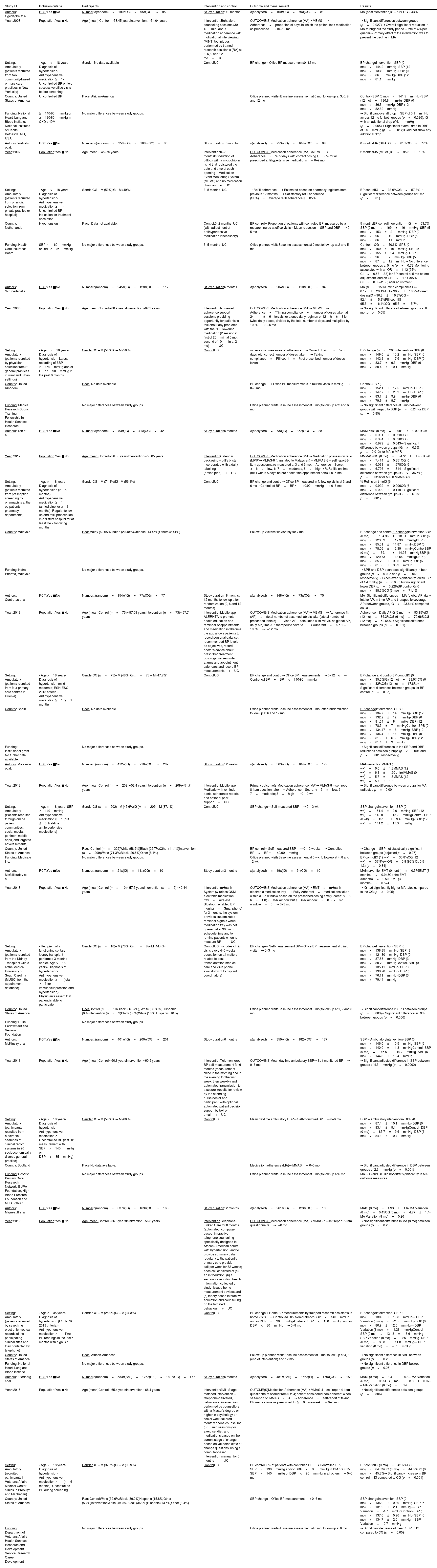

ResultsStudy characteristicsA total of 10 studies38–47 published between 2005 and 2018 met the inclusion criteria. Included studies comprised 2321 individuals. Study characteristics, intervention performed and outcomes are summarized on Table 1. Flowdiagram of literature search and selection process of included studies is presented in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Inclusion criteria | Participants | Intervention and control | Outcome and measurement | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors: Ogedegbe et al. | RCT:Yes ■No | Number:n(random)=190n(IG)=95n(CC)=95 | Study duration: 12 months | n(analyzed)=160n(IG)=79n(CG)=81 | MA (postintervention)IG – 57%CG – 43% |

| Year: 2008 | Population:Yes ■No | Age (mean):Control: ∼53.45 yearsIntervention: ∼54.04 years | Intervention:Behavioral counseling sessions (30–40min) about medication adherence with motivational interviewing (MINT) techniques performed by trained research assistants (RA) at 3, 6, 9 and 12 mo+UC | OUTCOME(S)Medication adherence (MA)→ MEMS→ Adherence=proportion of days in which the patient took medication as prescribed→ 10–12 mo | → Significant differences between groups (p=0.027).→ Overall significant reduction in MA throughout the study period – rate of 4% per quarter→ Primary effect of the intervention was to prevent the decline in MA |

| Setting: Ambulatory (patients recruited from two community-based primary care practices in New York city) | - Age>18 years- Diagnosis of hypertension- Antihypertensive medication ≥1- Uncontrolled BP on two successive office visits before screening | Gender: No data available | ControlUC | BP change→ Office BP measurements0–12 mo | BP changeIntervention- SBP (0 mo)=144.2mmHg- SBP (12 mo)=133.0mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=86.0mmHg- DBP (12 mo)=81.1mmHg |

| Country: United States of America | Uncontrolled BP | Race: African-American | Office planned visits- Baseline assessment at 0 mo; follow-up at 3, 6, 9 and 12 mo | Control- SBP (0 mo)=141.9mmHg- SBP (12 mo)=136.8mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=86.3mmHg- DBP (12 mo)=82.82mmHg | |

| Funding: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA | ≥140/90mmHg or ≥130/80mmHg in CKD or DM | No major differences between study groups. | → Significant overall drop in SBP of 5.1mmHg across 12 mo for both groups (p=0.026); IG with an additional drop of 6.1mmHg (p=0.065)→ Significant overall drop in DBP of 3.5mmHg (p=0.01); IG did not show any additional drop | ||

| Authors: Wetzels et al. | RCT:Yes ■No | Number:n(random)=258n(IG)=168n(CC)=90 | Study duration: 5 months | n(analyzed)=253n(IG)=164n(CG)=89 | 0 monthsMA (SRA)IG=81%CG=77% |

| Year: 2007 | Population:Yes ■No | Age (mean)∼45–75 years | Intervention0–2 monthsIntroduction of pillbox with a microchip in its lid that registered the date and time of each opening – Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) and no medication changes+UC | OUTCOME(S)Medication adherence (MA)→MEMS→ Adherence=% of days with correct dosing ≥85% for all prescribed antihypertensive medications→ 0–2 mo | 2 monthsMA (MEMS)IG=95.3±10% |

| Setting: Ambulatory (patients recruited from physician selection from private practice or hospital) | - Age>18 years- Diagnosis of hypertension- Antihypertensive medication ≥1- Uncontrolled BP- Indication for treatment escalation | GenderCG – M (59%)IG – M (49%) | 3–5 months- UC | → Refill adherence→ Estimated based on pharmacy registers from previous 12 months→ Satisfactory refill adherence (SRA)=average refill adherence ≥85% | BP controlIG=38.6%CG=57.8%→ Significant difference between groups at 2 mo (p<0.01) |

| Country: Netherlands | Hypertension | Race: Data not available. | Control:0–2 months- UC (with adjustment of antihypertensive medication if necessary) | BP control→ Proportion of patients with controled BP, measured by a research nurse at office visits→ Mean reduction in SBP and DBP→ 0–5 mo | 5 monthsBP controlIntervention – IG=53.7%- SBP (0 mo)=169±16mmHg- SBP (5 mo)=153±21mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=96±10mmHg- DBP (5 mo)=86±11mmHg |

| Funding: Health Care Insurance Board | SBP ≥160mmHg or DBP ≥95mmHg | No major differences between study groups. | 3–5 months- UC | Office planned visitsBaseline assessment at 0 mo; follow-up at 2 and 5 mo | Control – CG=50.6%- SPB (0 mo)=169±16mmHg- SBP (5 mo)=155±24mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=96±7mmHg- DBP (5 mo)=87±12mmHg→ No difference between groups at 5 mo (p=0.73)Monitoring associated with an OR=1.12 (95% CI=0.67–1.88) for BP control at 5 mo before adjustment, and an OR=1.11 (95% CI=0.59–2.08) after adjustment. |

| Authors: Schroeder et al. | RCT:Yes ■No | Numbern(random)=245n(IG)=128n(CG)=117 | Study duration6 months | n(analysed)=204n(IG)=110n(CG)=94 | MA (n=159)Timing complianceIG – 87.2±20.1%CG – 90.2±16.2%Correct dosingIG – 90.8±16.8%CG – 92.4±15.2%Pill countIG – 95.6±16.4%CG – 95.6±15.7% |

| Year: 2005 | Population:Yes ■No | Age (mean)Control∼68.2 yearsIntervention∼67.9 years | InterventionNurse-led adherence support sessions providing opportunity for patients to talk about any problems with their BP lowering medication (2 sessions: first of 20min at 0 mo; second of 10min at 2 mo)+UC | OUTCOME(S)Medication adherence (MA)→ MEMS→ Adherence=‘Timing compliance=number of doses taken at 24h±6 intervals for a once daily regimen or 12h±3 for twice daily doses, divided by the total number of days and multiplied by 100%→ 0–6 mo | → No significant difference between groups at 6 mo (p>0.05) |

| Setting: Ambulatory (patients recruited by physician selection from 21 general practices in rural and urban settings) | - Age>18 years- Diagnosis of hypertension- Latest recording of SBP ≥150mmHg and/or DBP ≥90mmHg in the past 6 months | GenderCG – M (54%)IG – M (56%) | ControlUC | → Less strict measures of adherence→ Correct dosing=% of days with correct number of doses taken→ Taking compliance=Pill count=% of prescribed number of doses taken | BP change (n=200)Intervention- SBP (0 mo)=149.0±15.2mmHg- SBP (6 mo)=142.9±17.6mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=83.7±9.3mmHg- DBP (6 mo)=80.4±10.1mmHg |

| Country: United Kingdom | Race: No data available. | BP change→ Office BP measurements in routine visits in mmHg→ 0–6 mo | Control- SBP (0 mo)=152.1±17.5mmHg- SBP (6 mo)=147.7±20.9mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=83.1±9.9mmHg- DBP (6 mo)=79.9±9.7mmHg | ||

| Funding: Medical Research Council Training Fellowship in Health Services Research | No major differences between study groups. | Office planned visitsBaseline assessment at 0 mo; follow-up at 2 and 6 mo | → No significant difference at 6 mo between groups with regard to SBP (p=0.24) or DBP (p=0.85) | ||

| Authors: Tan et al. | RCT:Yes ■No | Number:n(random)=83n(IG)=41n(CG)=42 | Study duration6 months | n(analysed)=73n(IG)=35n(CG)=38 | MAMPRIG (0 mo)=0.991±0.022IG (6 mo)=0.991±0.023CG (0 mo)=0.994±0.020CG (6 mo)=0.979±0.043→ Significant difference between groups (IG>0.6%; p=0.012) for MA in MPR |

| Year: 2017 | Population:Yes ■No | Age (mean)Control∼56.55 yearsIntervention∼55.85 years | InterventionCalendar packaging – pill's blister incorporated with a daily labelling (amlodipine)+UC | OUTCOME(S)Medication adherence (MA)→ Medication possession ratio (MPR)→ MMAS-8 (translated to Malaysian) – MMMAS-8 – self report 8-item questionnaire measured at 3 and 6 mo;Adherence – Score: <6=low, 6–7=moderate, 8=high→ % Refills on time (refill within 5 days before or after the appointment date)→ 0–6 mo | MMMAS-8IG (0 mo)=6.472±1.455IG (6 mo)=7.414±0.851CG (0 mo)=6.033±1.678CG (6 mo)=6.796±1.314→ Significant difference between groups (IG>36.5%; p=0.029) for MA in MMMAS-8 |

| Setting: Ambulatory (patients recruited from prescription screening by pharmacists at the outpatients’ pharmacy departments) | - Age >18 years- Diagnosis of hypertension (≥6 months)- Antihypertensive medication ≥1 (amlodipine for ≥3 months)- Regular follow-up and refill prescription in a district hospital for at least the 7 following months | GenderCG – M (71.4%)IG –M (56.1%) | ControlUC | BP change and control→ Office BP measured in follow-up visits at 3 and 6 mo→ Controlled BP=BP ≤140/90mmHg→ 0–6 mo | % Refills on timeIG (6 mo)=0.992±0.006CG (6 mo)=0.929±0.119→ Significant difference between groups (IG>6.3%; p=0.001) |

| Country: Malaysia | RaceMalay (62.65%)Indian (20.48%)Chinese (14.46%)Others (2.41%) | Follow-up visits/refillsMonthly for 7 mo | BP change and controlBP changeInterventionSBP (0 mo)=134.96±18.31mmHgSBP (6 mo)=123.59±17.38mmHgDBP (0 mo)=85.51±11.87mmHgDBP (6 mo)=78.06±12.39mmHgControlSBP (0 mo)=139.11±14.95mmHgSBP (6 mo)=129.73±13.54mmHgDBP (0 mo)=85.72±9.86mmHgDBP (6 mo)=81.36±9.99mmHg | ||

| Funding: Kotra Pharma, Malaysia | No major differences between study groups. | → SPB and DBP decreased significantly in both groups (p=0.005 and p=0.043, respectively)→ IG achieved significantly lowerSBP of 4.4 mmHg (p=0.035) but no significant lower DBP (p=0.228)BP controlIG (6 mo)=88.6%CG (6 mo)=71.1% | |||

| Authors: Contreras et al. | RCT:Yes ■No | Numbern(random)=154n(IG)=77n(CG)=77 | Study duration18 months; 12 months follow up after randomization (0, 6 and 12 months) | n(analysed)=148n(IG)=73n(CG)=75 | MA- Significant differences in MA (global AP, daily intake AP, in time AP and therapeutic coverage AP) between groups, IG>23.64% compared do CG |

| Year: 2018 | Population:Yes ■No | Age (mean)Control (n=75)∼57.08 yearsIntervention (n=73)∼57.7 years | InterventionMobile app ALERHTA to promote health education and reminder of appointments and medication intake time; the app allows patients to record personal data, set recommended BP levels as objectives, record doctor's advice about prescribed treatment, posology, set reminder alarms and appointment calendars and record BP measurements+UC | OUTCOME(S)Medication adherence (MA)→ MEMS→ Adherence % (AP)=(total number of assumed tablets taken)/(total number of prescribed tablets)→ Mean AP – calculated with MEMS as global AP, daily AP, time AP, therapeutic cover AP→ Adherent=AP 80–100%→ 0–12 mo | Adherence – Daily APIG (6 mo)=93.15%IG (12 mo)=86.3%CG (6 mo)=70.66%CG (12 mo)=62.66%→ Significant difference between groups (p<0.001) |

| Setting: Ambulatory (patients recruited from four primary care centres in Huelva) | - Age >18 years- Diagnosis of hypertension (mild-moderate; ESH-ESC 2013 criteria)- Antihypertensive medication ≥1 (≥1 month) | GenderCG (n=75)– M (48%)IG (n=73)– M (47.9%) | ControlUC | BP change and control→ Office BP measurements→ 0–12 mo→ Controlled BP=BP<140/90mmHg | BP change and controlBP controlIG (0 mo)=35.6%IG (12 mo)=38.6%CG (0 mo)=32%CG (12 mo)=17.8%→ Significant differences between groups for BP control (p<0.05) |

| Country: Spain | Race: No data available | Office planned visitsBaseline assessment at 0 mo (after randomization); follow-up at 6 and 12 mo | BP changeIntervention- SPB (0 mo)=134.7±14mmHg- SBP (12 mo)=132.2±12mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=81.64±8mmHg- DBP (12 mo)=78.5±7mmHgControl- SPB (0 mo)=134.47±8mmHg- SBP (12 mo)=134.4±11mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=81.9±6.8mmHg- DBP (12 mo)=81.4±9mmHg | ||

| Funding: Institutional grant. No further data available. | No major differences between study groups. | → Significant differences in the SBP and DBP reductions between groups (p<0.001 and p<0.001, respectively) | |||

| Authors: Morawski et al. | RCT:Yes ■No | Numbern(random)=412n(IG)=210n(CG)=202 | Study duration12 weeks | n(analysed)=363n(IG)=184n(CG)=179 | MAInterventionMMAS (0 wk)=6.0±1.8MMAS (12 wk)=6.3±1.6ControlMMAS (0 wk)=5.7±1.8MMAS (12 wk)=5.7±1.8 |

| Year: 2018 | Population:Yes ■No | Age (mean)Control (n=202)∼52.4 yearsIntervention (n=209)∼51.7 years | InterventionMobile app Medisafe with reminder alerts, adherence reports, and optional peer support+UC | Primary outcome(s)Medication adherence (MA)→ MMAS-8 – self report 8-item questionnaire→ Adherence – Score: <6=low; 6–7=moderate; 8=high→ 0–12 wk | → Significant difference between groups for MA (adjusted p=0.001) |

| Setting: Ambulatory (Patients recruited through online patient communities, social media, pertinent mobile apps, and targeted advertisements) | - Age >18 years- SBP ≥140mmHg- Antihypertensive medication ≥1 (but ≤3, first-line antihypertensive medications) | GenderCG (n=202)– M (45.6%)IG (n=209)– M (37.1%) | ControlUC | SBP change→ Self-measured SBP→ 0–12 wk | SBP changeIntervention- SBP (0 wk)=151.4±9.0mmHg- SBP (12 wk)=140.8±15.7mmHgControl- SBP (0 wk)=151.3±9.4mmHg- SBP (12 wk)=141.2±17.3mmHg |

| Country: United States of America | Race:Control (n=202)White (58.9%)Black (29.7%)Other (11.4%)Intervention (n=209)White (71.3%)Black (20.6%)Other (8.1%) | BP control→ Self-measured SBP→ 0–12 weeks→ Controlled BP=BP ≤140/90mmHg | → Change in SBP not statistically significant between groups (adjusted p=0.97) | ||

| Funding: Medisafe Inc. | No major differences between study groups. | Office planned visitsBaseline assessment at 0 wk; follow-up at 4, 8 and 12 wk | BP controlIG (12 wk)=35.8%CG (12 wk)=37.9%→ OR=0.8 (95% CI, 0.5–1.3) (p=0.34) | ||

| Authors: McGillicuddy et al. | RCT:Yes ■No | Numbern(random)=21n(IG)=11n(CG)=10 | Study duration3 months | n(analysed)=19n(IG)=9n(CG)=10 | MAInterventionEMT (0month)=0.576EMT (3 months)=0.945ControlEMT (0month)=0.500EMT (3 months)=0.574 |

| Year: 2013 | Population:Yes ■No | Age (mean)Control (n=10)∼57.6 yearsIntervention (n=9)∼42.44 years | InterventionmHealth System (wireless GSM electronic medication tray+wireless Bluetooth enabled BP monitor+Smartphone) for 3 months; the system provides customizable reminder signals when medication tray was not opened after 30min of schedule time and to remind patients when to measure BP+UC | OUTCOME(S)Medication adherence (MA)→ EMT=mHealth electronic medication tray→ Fully Adherent=medications taken within a 3-h window based on the prescribed dosing time; Scores: ≤3-h=1.0; >3-h window but ≤6-h window=0.5; >6-h window=0→ 0–3 mo | → IG had significantly higher MA rates compared to the CG (p<0.05) |

| Setting: Ambulatory (patients recruited from the Kidney Transplant Clinic at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) from the appointment database) | - Recipient of a functioning solitary kidney transplant performed 3-months earlier- Age >18 years- Diagnosis of hypertension- Antihypertensive medication ≥1 (total ≥3 for immunosuppression and hypertension)- Physician's assent that patient is able to participate | GenderCG (n=10)– M (70%)IG (n=9)– M (44.4%) | ControlUC (includes clinic visits every 4–6 weeks; education on all matters related to post-transplantation medical care and 24-h phone availability of transplant coordinators) | BP change→ Self-measurement BP→ Office BP measurement at clinic visits→ 0–3 mo | BP changeIntervention- SBP (0 mo)=138.35mmHg- SBP (3 mo)=121.80mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=87.55mmHg- DBP (3 mo)=80.70mmHgControl- SBP (0 mo)=135.11mmHg- SBP (3 mo)=138.78mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=76.11mmHg- DBP (3 mo)=79.44mmHg |

| Country: United States of America | RaceControl (n=10)Black (66.67%), White (33.33%), Hispanic (0%)Intervention (n=9)Black (80%)White (10%) Hispanic (10%) | Office planned visitsBaseline assessment at 0 mo; follow-up at 1, 2 and 3 mo | → Significant difference in SPB between groups (p=0.009)→ Significant difference in DBP between groups (p=0.006) | ||

| Funding: Duke Endowment and Verizon Foundation | No major differences between study groups. | ||||

| Authors: McKinstry et al. | RCT:Yes ■No | Numbern(random)=401n(IG)=200n(CG)=201 | Study duration6 months | n(analysed)=359n(IG)=182n(CG)=177 | SBP – AmbulatoryIntervention- SBP (0 mo)=146.0±10.5mmHg- SBP (6 mo)=140.0±11.3mmHgControl- SBP (0 mo)=146.5±10.7mmHg- SBP (6 mo)=144.3±13.4mmHg |

| Year: 2013 | Population:Yes ■No | Age (mean)Control∼60.8 yearsIntervention∼60.5 years | InterventionTelemonitored BP self-measurement for 6 months (measurement twice in the morning and in the evening for the first week; then weekly) and automated transmission to a secure website for review by the attending nurse/doctor and participant, with optional automated patient decision support by text or email+UC | OUTCOME(S)Mean daytime ambulatory SBP→ Self-monitored BP→ 0–6 mo | → Significant adjusted difference in SBP between groups of 4.3mmHg (p=0.0002) |

| Setting: Ambulatory (participants recruited from electronic searches of clinical record systems in 20 socioeconomically diverse general practice) | - Age >18 years- Diagnosis of hypertension- Antihypertensive medication ≥1- Uncontrolled BP (last BP measurement with SBP>145mmHg or DBP>85mmHg) | GenderCG – M (59%)IG – M (60%) | ControlUC | Mean daytime ambulatory DBP→ Self-monitored BP→ 0–6 mo | DBP – AmbulatoryIntervention- DBP (0 mo)=87.4±10.1mmHg- DBP (6 mo)=83.4±9.1mmHgControl- DBP (0 mo)=85.7±9.6mmHg- DBP (6 mo)=84.3±10.4mmHg |

| Country: Scotland | Race:No data available. | Medication adherence (MA)→ MMAS→ 0–6 mo | → Significant adjusted difference in DBP between groups of 2.3mmHg (p=0.001) | ||

| Funding: Scottish Primary Care Research Network. BUPA Foundation, High Blood Pressure Foundation and NHS Lothian. | No major differences between study groups. | Office planned visitsBaseline assessment at 0 mo; follow-up at 6 mo | MA→ IG and CG did not differ significantly in MA outcome measures | ||

| Authors: Migneault et al. | RCT:Yes ■No | Numbern(random)=337n(IG)=169n(CG)=168 | Study duration12 months | n(analysed)=261n(IG)=123n(CG)=138 | MAIG (0 mo)=4.93±1.6- MA Variation (8 mo)=0.45CG (0 mo)=4.77±1.4- MA Variation (8 mo)=0.26 |

| Year: 2012 | Population:Yes ■No | Age (mean)Control∼56.8 yearsIntervention∼56.3 years | InterventionTelephone-Linked Care for 8 months (automated, computer-based, interactive telephone counseling specifically designed to African–American adults with hypertension) and to provide summary data regularly to the patient's primary care provider; 1 call per week for 32 weeks; each call consisted of (a) an introduction, (b) a section for reporting health information collected on study- issued home measurement devices and (c) theory based interactive education and counselling on the targeted behaviour+UC | OUTCOME(S)Medication adherence (MA)→ MMAS-7 – self report 7-item questionnaire→ 0–8 mo | → Not significant difference in MA (8 mo) between groups (p=0.25) |

| Setting: Ambulatory (patients recruited by searching electronic medical records of the participating clinical sites and then contacted by telephone) | - Age ≥35 years- Diagnosis of hypertension (ESH-ESC 2013 criteria)- Antihypertensive medication ≥1- Two BP readings in the last 6 months with high BP | GenderCG – M (25.0%)IG – M (34.3%) | ControlUC | BP change→ Home BP measurements by trainped research assistants in home visits→ Controlled BP- Non-diabetic: SBP<140mmHg and/or DBP<90mmHg-Diabetic: SBP<130mmHg and/or DBP<80mmHg→ 0–8 mo | BP changeIntervention- SBP (0 mo)=130.6±19.8mmHg--- SBP Variation (8 mo)=−2.06mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=80.9±12.5mmHg--- DBP Variation (8 mo)=-1.28mmHgControl- SBP (0 mo)=131.8±18.6mmHg--- SBP Variation (8 mo)=0.25mmHg- DBP (0 mo)=80.3±11.8mmHg--- DBP variation (8 mo)=−0.1mmHg |

| Country: United States of America | Race: African-American | Follow-up planned visitsBaseline assessment at 0 mo; follow-up at 4, 8 (end of intervention) and 12 mo | → No significant difference in SBP between groups (p=0.25) | ||

| Funding: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute | No major differences between study groups. | → No significant difference in DBP between groups (p=0.25) | |||

| Authors: Friedberg et al. | RCT:Yes ■No | Numbern(random)=533n(SMI)=176n(HEI)=180n(CG)=177 | Study duration6 months | n(analysed)=481n(SMI)=156n(EI)=170n(CG)=159 | MAIG (0 mo)=3.4±0.07--- MA Variation (6 mo)=0.25CG (0 mo)=3.3±0.07--- MA Variation (6 mo)=0.14 |

| Year: 2015 | Population:Yes ■No | Age (mean)Control∼65.4 yearsIntervention∼66.4 years | InterventionSMI –Stage-matched intervention – telephone-delivered, behavioural intervention performed by counsellors with a Master's degree or higher in psychology or social work (tailored monthly phone counselling (30min sessions) for exercise, diet, and medications based on the current stage of change based on validated state of change questions, using a computer-based intervention manual) for 6 months+UC | OUTOME(S)Medication Adherence (MA)→ MMAS-4 – self report 4-item questionnaire scored from 0 to 4; patient considered non-adherent when self-report on MMAS<4→ Adherence=self-report of taking BP medications as prescribed for ≥6 days/week→ 0–6 mo | → Not significant differences between groups (p=0.306) |

| Setting: Ambulatory (recruited participants in Veterans Affairs Medical Center clinics in Brooklyn and Manhattan) | - Age >18 years- Diagnosis of hypertension- Antihypertensive medication ≥1 (≥6 months)- Uncontrolled BP during screening | GenderCG – M (97.7%)IG – M (98.9%) | ControlUC | BP control→ % of patients with controlled BP→ Controlled BP- SBP<130mmHg and/or DBP<80mmHg in DM or CKD- SBP<140mmHg or DBP<90mmHg in all others→ 0–6 mo | BP controlIG (0 mo)=42.6%IG (6 mo)=64.6%CG (0 mo)=44.6%CG (6 mo)=45.8%→ Significantly increase in BP control in IG compared to CG (p=0.001) |

| Country: United States of America | RaceControlWhite (39.6%)Black (39.0%)Hispanic (15.8%)Other (5.7%)InterventionWhite (46.0%)Black (36.9%)Hispanic (13.6%)Other (3.4%) | SBP change→ Office BP measurement→ 0–6 mo | SBP changeIntervention- SBP (0 mo)=136.0±0.89mmHg- SBP (6 mo)=131.2±2.1mmHg--- SBP Variation=-4.7mmHgControl- SBP (0 mo)=137.0±0.96mmHg- SBP (6 mo)=134.7±2.0mmHg--- SBP Variation=-2.7mmHg | ||

| Funding: Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service Research Career Development | No major differences between study groups. | Office planned visits- Baseline assessment at 0 mo; follow-up at 6 mo | → Significant decrease of mean SBP in IG compared to CG (p=0.009) | ||

Abbreviations: % – percentage, AP – adherence percentage, BP – blood pressure, CG – control group, CI – confidence interval, CKD – chronic kidney disease, DBP – diastolic blood pressure, DM – diabetes mellitus, EMT – electronic monitoring tray, ESH-ESC – European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology, HEI – health education intervention, IG – intervention group, M – male, MA – medication adherence, MEMS – medical events monitoring system, MMAS – Morisky Medication Adherence Scale, MPR – medication possession ratio, min – minutes, MINT – motivational interviewing, mo – months, OR – odds ratio, RA – research assistants, RCT – randomized control trial, SBP – systolic blood pressure, SMI – stage-matched intervention, SRA – satisfactory refill adherence, UC – usual care, wk – weeks.

All included studies were RCTs with an ambulatory setting. Studies were conducted in the United States of America,38,43,44,46,47 Europe39,40,42,45 and Malaysia.41

Sample sizes ranged from 21 to 533 participants, with a mean age ranging from 42.44 to 75 years old. Several motivational interventions performed were: behavioral counseling by health providers,38–40 compliance dispensers,39,41 blood pressure self-measurement,43–45 social support,43 telephone-linked computer counseling,45–47 mobile applications with medication intake42–44 and/or BP target levels reminders.42

The primary outcome was medication adherence measured in all studies included. Five studies41,43,45–47 used subjective measures such as MMAS, adapting the questionnaire to 4,47 745,46 or 841,43 questions and/or translating it to other language.41 Six studies38–42,44 measured pharmacologic compliance using objective measures with MEMS,38–40,42 pill count,40 refill pharmacy records39,41 or other validated scales such as medication possession ratio (MPR)41 and electronic medication tray (EMT).44

BP was the secondary outcome of this review and was also measured in all studies included. BP change was measured by health care providers – office BP38–47 – at planned visits or by the patient, using adequate provided equipment – self BP.43–45 Results were displayed in different ways: either as mean scores in the chosen scale, mean differences between pre- and post-intervention intention or calculated odds ratio.

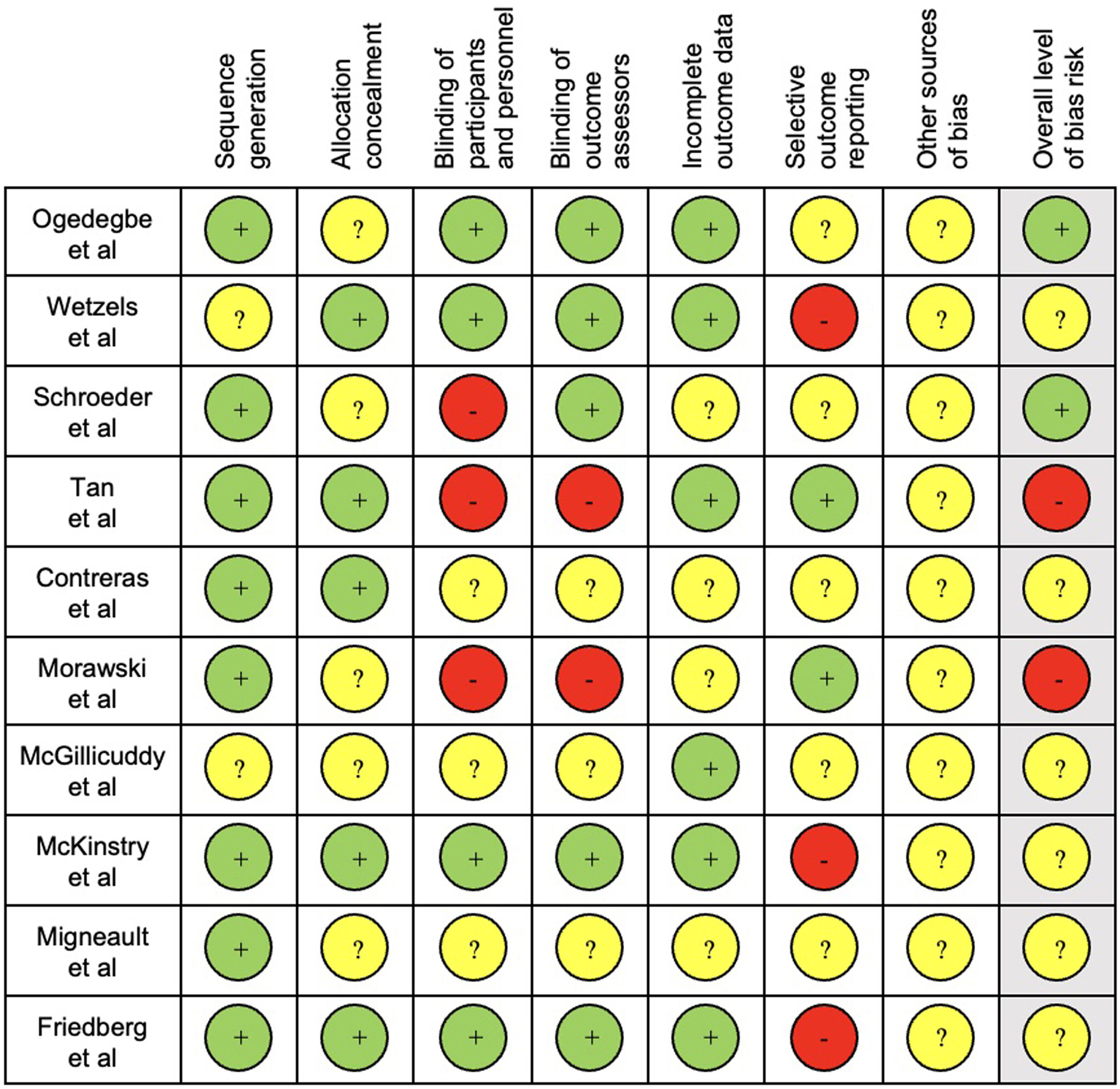

The results of quality assessment are presented in Fig. 2.

For quality assessment, sequence generation and blinding of outcome assessors were considered the key items as these were the most likely to produce significant bias in this type of interventions and outcomes. Seven studies39,41,43–47 had an unclear overall bias risk, as one or more key domains were considered “unclear” and three38,40,42 were considered low.

Medication adherenceFive authors38,41–44 reported a significant difference of medication adherence between intervention and control groups.

In Ogedegbe et al.,38 behavioral counseling sessions were performed by trained assistants using motivational interviewing (MINT) techniques of 30–40min and took place at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months of intervention. The results for medication adherence showed a significant difference favoring the intervention group (p=0.027).

Tan et al.41 was a two-arm study. A calendar packaging, which consisted on a pill's blister incorporated with a daily labeling, was provided to the intervention group. In this trial, medication adherence at 6 months had a significant improvement in intervention group in all measurements – MPR (p=0.012), MMAS-8 (p=0.029) and refills (p=0.001).

In Contreras et al.,42 the intervention group used a mobile app – ALERHTA. The app allows patients to record personal data, BP measurements, doctor's advice and posology about prescribed treatment, set reminders, appointment calendars and recommended BP levels. 12 months after randomization adherence percentage (AP) mean was 23.76% higher in the intervention group (p<0.001).

Morawski et al.43 described a mobile app that allowed setting reminders, delivering adherence reports, BP tracking and offered peer support through a “Medfriend” who is warned when doses are missed. At 12 weeks, there was a significant difference between study groups (p=0.001), favoring the intervention.

In McGillicuddy et al.44 study, 9 patients received an intervention based on mHealth System. This system consisted on a wireless EMT, a Bluetooth enabled BP monitor and a smartphone. Alarms were sent to patient's phone to remind them to measure BP and whenever the medication tray was not opened. Final assessment at 3 months revealed a significant higher adherence rate in intervention group when compared t42o control group (p<0.05).

Blood pressureFive trials obtained significant results regarding BP reduction41,42,44,45,47 and three presented significant differences in BP control.39,42,47 One study39 focused only in BP control but presented SBP and DBP values.

In four studies38,40,44,45 no control of BP was mentioned and in one41 there was not a statistical comparison regarding control of BP.

Tan et al.41 defined “controlled BP” as BP<140/90mmHg. Results showed a significant SBP and DBP reduction for both groups at 6 months (p=0.005 for SBP and p=0.043 for DBP), with an additional 4.4mmHg reduction of SBP in intervention group (p=0.035) but no drop of DBP (p=0.228).

Contreras et al.42 defined “controlled BP” as BP<140/90mmHg. At 12 months significant differences were found for BP control (p<0.05) and both SBP and DBP reductions were found (p<0.001 and p<0.001, respectively) in the intervention group.

In Wetzels et al.,39 from 0 to 2 months, the intervention group received MEMS, a pillbox with a microchip in its lid that registered the date and time of each opening. At 2 months, 38.6% of patients from intervention group achieved BP control against 57.8% of controls (p<0.01). At 5 months, 53.7% of intervention group and 50.6% of control group reached BP control (p=0.73). MEMS associated with an OR=1.11 (95% CI=0.59–2.08) for BP control at 5 months after adjustment.

Friedberg et al.47 was a three-arm trial but we only considered the Stage-Matched Intervention (SMI) and the control arm. SMI consisted on telephone-delivered, behavioral intervention sessions performed by counselors. 30min sessions for exercise, diet, and medication-related behavioral counseling, based on the current stage of change using a computer-based manual. “Controlled BP” was defined as SBP<130mmHg and/or DBP<80mmHg in diabetes mellitus (DM) or chronic kidney disease (CKD) and SBP<140mmHg or DBP<90mmHg in all other patients. Results pointed out a significantly increase in BP control in intervention (64.6%) compared to control group (45.9%) at 6 months (p=0.001). Mean SBP was significantly decreased in intervention compared to control at 6 months (p=0.009).

In Ogedegbe et al.38 results show a significant overall SBP reduction of 5.1mmHg and DBP reduction of 3.5mmHg across 12 months for both groups (p=0.026 for SBP and p=0.01 for DBP), with an additional 6.1mmHg reduction of SBP in intervention group (p=0.065) but no additional drop of DBP.

McGillicuddy et al.44 described as intervention the mHealth System. SPB (p=0.009) and DBP (p=0.006) were both reduced in the intervention arm.

In McKinstry et al.,45 the intervention consisted on telemonitored self-BP measurements for 6 months and automated data transmission to a secure website for review by the attending nurse or doctor and participant, with an automated patient decision support by text or email. Results showed a significant adjusted difference in SBP between groups of 4.3mmHg (p=0.0002) and in DBP of 2.3mmHg (p=0.001).

Three studies40,43,46 did not find significant results in any BP outcome.

Schroeder et al.40 evaluated nurse-led adherence support sessions in which patients could talk about difficulties related to antihypertensive medication. Two sessions were performed. One at the beginning (lasting 20min) and another 2 months later (10min). Outcomes did not have a significant difference between groups at 6 months (medication adherence p>0.05; SBP p=0.24; DBP p=0.85).

Migneault et al.46 had Telephone-Linked Care intervention for 8 months, an automated, computer-based, interactive telephone counseling system. This provided data to the patient's primary care physician. The system consisted on 1 call per week for 32 weeks; each with a section for reporting health information collected on study-issued home measurement devices and a theory based interactive education and counseling on the targeted behavior. “Controlled BP” was defined as SBP<140mmHg and/or DBP<90mmHg for non-diabetic patients and for diabetic as SBP<130mmHg and/or DBP<80mmHg. Significant differences between groups at 8th month were not found for either outcome (medication adherence p=0.25; SBP and DBP p=0.25).

The 5 studies reporting complete data on SBP events38,39,42,43,47 enrolled 1191 participants. On pooled analysis, motivational interventions were not significantly associated with variation in SBP (Mean Difference, −0.06; 95%CI, −0.05 to 0.18; p=0.63; I2=0.0%) (Fig. 3). A low heterogeneity was observed in the analysis.

The 3 studies reporting complete data on DBP events38,39,42 events included 514 participants.

On pooled analysis, motivational interventions were not significantly associated with variation in DBP (mean difference, −0.11; 95% CI, −0.10 to 0.31; p=0.28; I2=23.8%) (Fig. 3). A low heterogeneity was observed in the analysis.

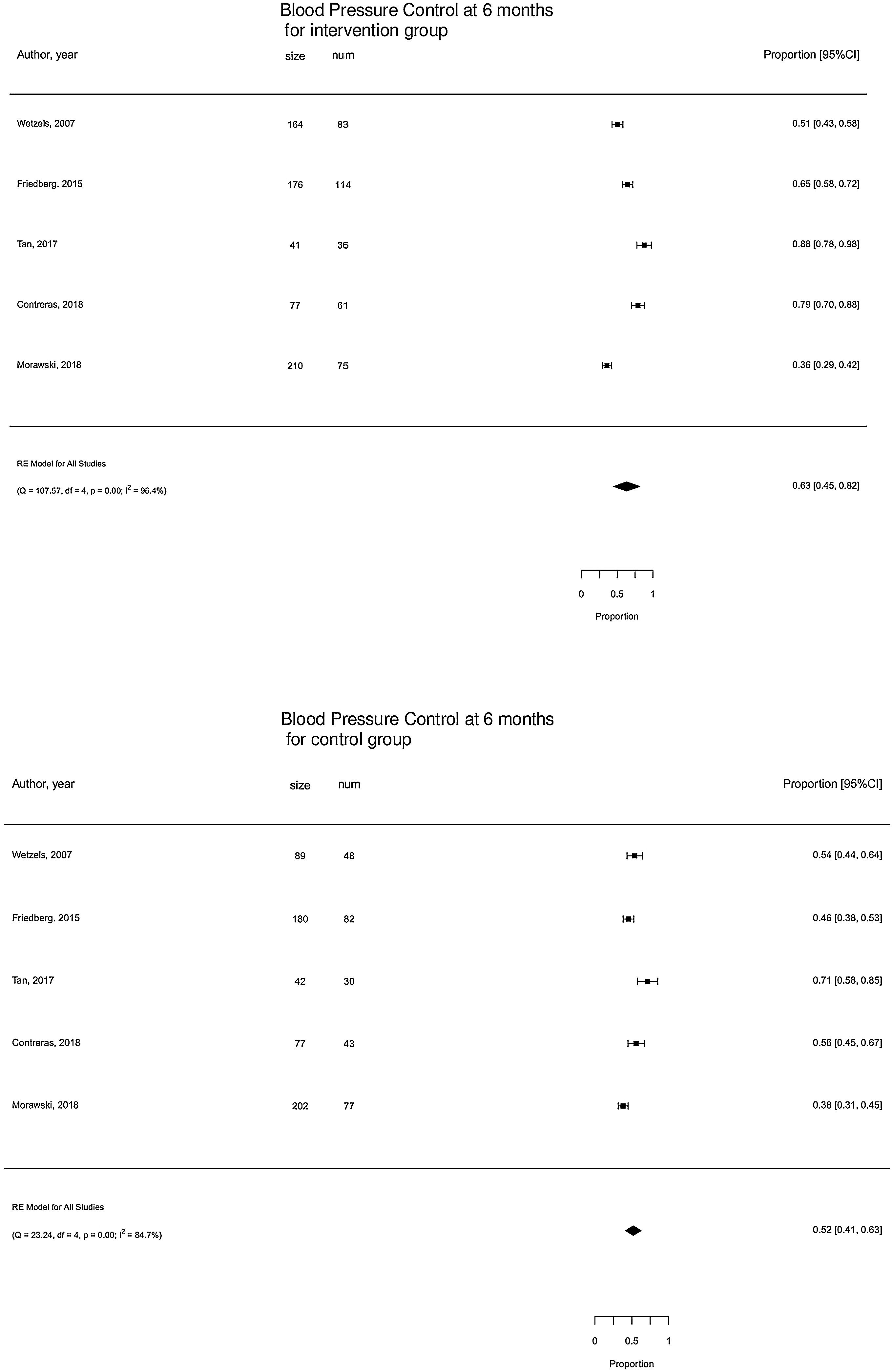

The 5 studies reporting complete data on BP Control39,41–43,47 events included 1037 participants. On pooled analysis, motivational interventions were not significantly associated with BP control. Mean percentage of controlled BP in motivational intervention was 63% (95% CI [45,82]%) versus 52% (95% CI [41,63]%) in control group (Fig. 4). High heterogeneity was observed in the analysis.

DiscussionThis study systematically reviewed motivational interventions to improve medication adherence and BP control and pointed out the interventions that showed benefit such as behavioral counseling,38,47 motivational interviewing38 compliance dispensers,41 electronic monitoring using mobile apps reminders and recorders,42–44 self-BP measurements43–45 and peer support.43

Our systematic review suggested that there might be effective motivational interventions to improve medication adherence and BP control in hypertensive patients.

Additionally, we reported the results of a meta-analysis to assess if motivational interventions to improve medication adherence were associated with significant improvement of systolic and diastolic reduction or BP control. To the best of our knowledge, the current study was the first meta-analysis to assess the association between motivational interventions and clinical outcomes.

Five out of ten authors included in our systematic review38,41–44 reported a statistically significant beneficial impact on medication adherence. In five out of ten studies there was a statistically significant improvement of BP values or BP control in the intervention group.41,42,44,45,47

In our meta-analysis to assess the effect of motivational interventions on SBP (five studies38,39,42,43,47), on DBP (three studies38,39,42) and a pool analysis to assess the effect of motivational interventions to improve BP control (5 studies39,41–43,47).

On pooled analysis, motivational interventions were not significantly associated with a systolic blood pressure (mean difference, −0.06; 95% CI, −0.05 to 0.18; p=0.63; I2=0.0%) or diastolic blood pressure (mean difference, −0.11; 95% CI, −0.10 to 0.31; p=0.28; I2=23.8%) decrease or Blood pressure control. Heterogeneity was low for the assessment of SBP outcome (I2=0.0%), low for DBP (I2=23.8%) and high for BP control.

In the conducted meta-analysis, the motivational interventions targeting medication adherence improved blood pressure outcomes, although not significantly. Regardless of heterogeneity, one potential limitation of this pooled analysis could be the inclusion of only two out of the five studies that significantly improved medication adherence41,42 found in our systematic review. These constraints, which were caused by a lack of data from the remaining articles may have influenced the results. Additionally, in the pooled analysis, there were a greater number of articles that did not demonstrate evidence of medication adherence.

Regarding the considered key domains of quality assessment, studies had mixed findings. Sequence generation had low risk of bias in most studies, with only two studies39,44 being unclear. Blinding of outcome assessors was considered unclear in six trials.41,43–47 Blinding of outcome assessors is also important to avoid “detection bias” and induce an overestimation of intervention effects. Subjective measurements might have been influenced by non-blindness of participants and assessors. Blinding of participants and personnel might influence adherence due to “performance bias”. Participants’ blinding is difficult to achieve as they might know the allocation by signing the consent form or during the intervention.

Findings of our study were consistent with studies48–50 that have evaluated the association between motivational interventions and other related medical conditions. In addition, a previous meta-analysis found consistent associations between motivational interviewing interventions and medication adherence in adults with chronic diseases.51

These data, combined, support the findings of our systematic review and meta-analysis.

Clinical significanceIt is observed that the difference in the variation of SBP between groups is on average 0.06; which means that in the intervention group the decrease in systolic blood pressure is greater than in the control group by an average of 0.06mmHg. It might have clinical relevance although it did not reach statistical significance, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.18].

The difference in variation of diastolic blood pressure between groups is on average 0.11; which means that in the intervention group the decrease in diastolic blood pressure is greater than in the control group by an average of 0.11mmHg. Likewise, it might have clinical relevance although it did not reach statistical significance, CI of 95% [−0.10, 0.31].

Compared with usual care, trials suggested no difference between BP control in the motivational intervention group at 6 months (Fig. 4).

Methodologic differences among studiesPooled association of medication adherence could not be performed owing to high heterogeneity due to considerable variation among strategies to assess adherence. One study did not measure adherence in the control group39 and in another42 patients had a different adherence cut-off.

Moreover, studies varied in the length of follow-up (from 3 to 12 months) and in the strategies to assess BP values and control. Office BP was measured at planned visits by healthcare providers or a research nurse38–42,44,45,47 self BP measurements at home43 and measurements by trained assistants in home visits46 were also used.

We found a wide variability in patient characteristics between studies, which may limit the generalizability of conclusions.

Another limitation of our review could be possible confounding variables such as participants’ age, socioeconomic status, years since the HTN diagnose, its etiology and medication.

Lack of uniformity in scales and/or variance in the cut points used within a given scale, particularly to BP assessment, may have also contributed to this heterogeneity. Furthermore, study population and the type of intervention were different in each study and it should be noted that the majority of studies did not report complete outcome data.

We expected to find a higher number of well-designed clinical trials with greater sample sizes and longer follow-up periods. Higher quality studies with well-designed accessible protocols and universal outcomes and assessment should be executed using objective reliable measures, also assessing the long-term impact of these interventions. Comparison with complex interventions using combined strategies should also be performed. Trials included in this review may also raise the question of technology use in healthcare settings.

ConclusionsThe findings suggest that Motivational interventions may improve medication adherence but not significantly blood pressure control in arterial hypertension, although evidence is still being drawn from few studies with unclear risk of bias.

Future studies should seek to compare different interventions and the use of technology in healthcare settings.

Ethical responsibilitiesFuture studies should seek to compare different interventions and the use of technology in healthcare settings.

FundingFinancial support from the University of Coimbra.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.