The differential diagnosis of focal liver lesions is widely debated and constantly updated in the field of gastroenterology. Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL), given its rarity, is one of the least considered differential diagnoses.1 These tumours are estimated to account for 0.016% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.2 The disease pathogenesis is not completely understood, but many studies have suggested that chronic antigen stimulation could be a risk factor. Some factors, such as hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) have been identified.3–5

Presentation is generally oligosymptomatic, with the most common symptom being abdominal pain,2 although there are also reports of fulminant liver failure as a result of the PHL.3 High clinical suspicion and relevant images are required for diagnosis of this entity, but histology is fundamental for confirmation and is invaluable in guiding treatment.

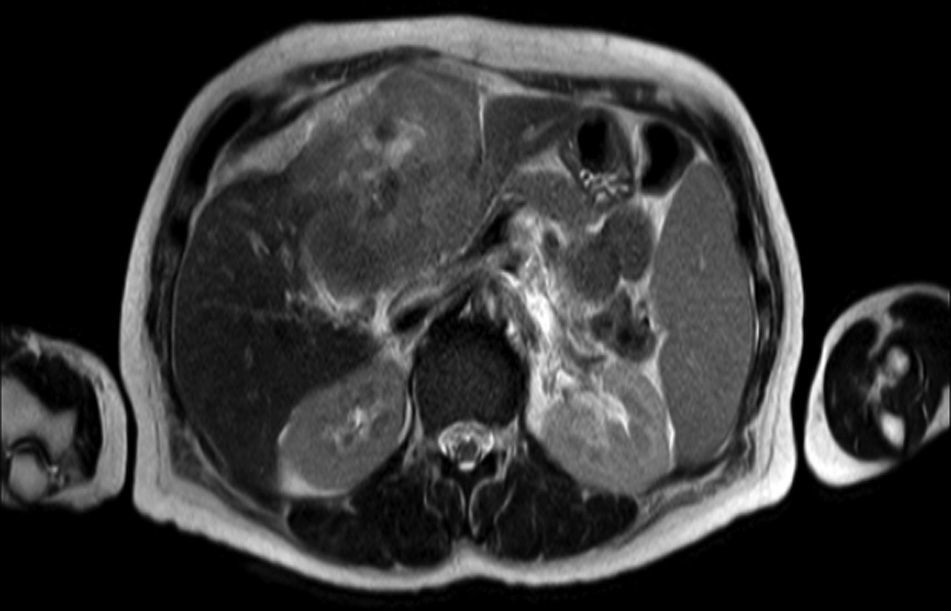

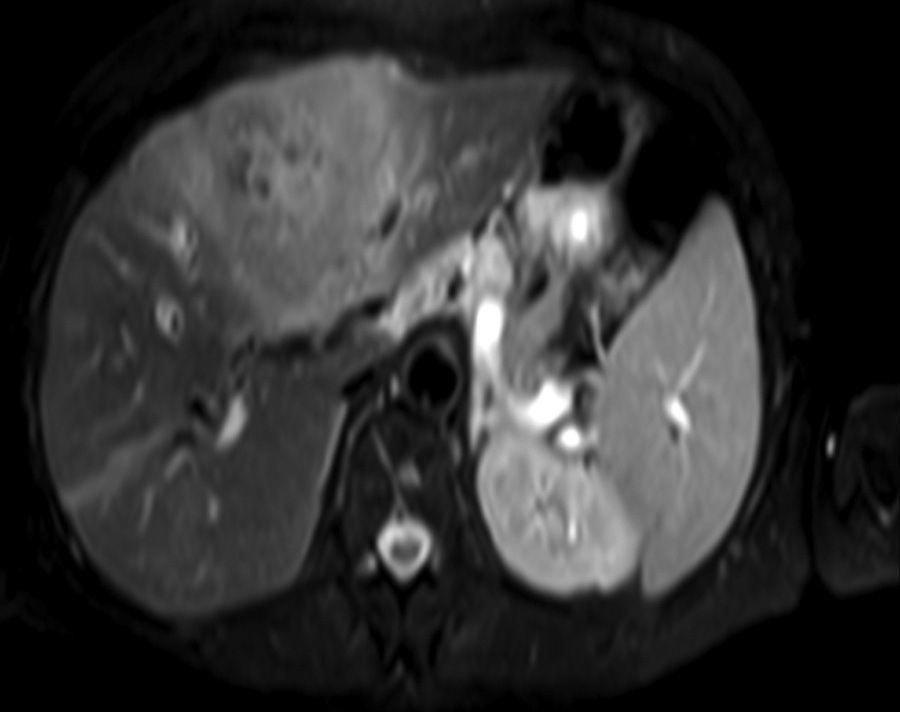

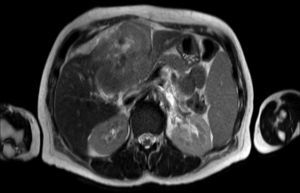

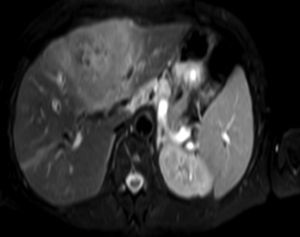

Clinical caseA 65-year-old woman with no relevant history presented with a 7-month history of symptoms characterised by diaphoresis, 10-kg weight loss and abdominal pain, mainly in the right hypochondrium. Physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory tests showed leukocytes 12500, with 65% neutrophils; liver function tests and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were normal. Abdominal ultrasound revealed the presence of a 7-cm liver mass with a neoplastic appearance in segment IVb. The study was complemented with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which showed retraction of the liver parenchyma and segmental dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct, suggestive of a focal liver lesion with a neoplastic appearance, consistent with cholangiocarcinoma (Figs. 1 and 2); a thin-walled gallbladder containing no calculi was also seen, but no lymphadenopathies, splenomegaly or other lesions suggestive of metastasis. The patient was admitted to the surgery department, where she underwent extended left hepatectomy plus lymphadenectomy. She progressed well, with no complications in the postoperative period.

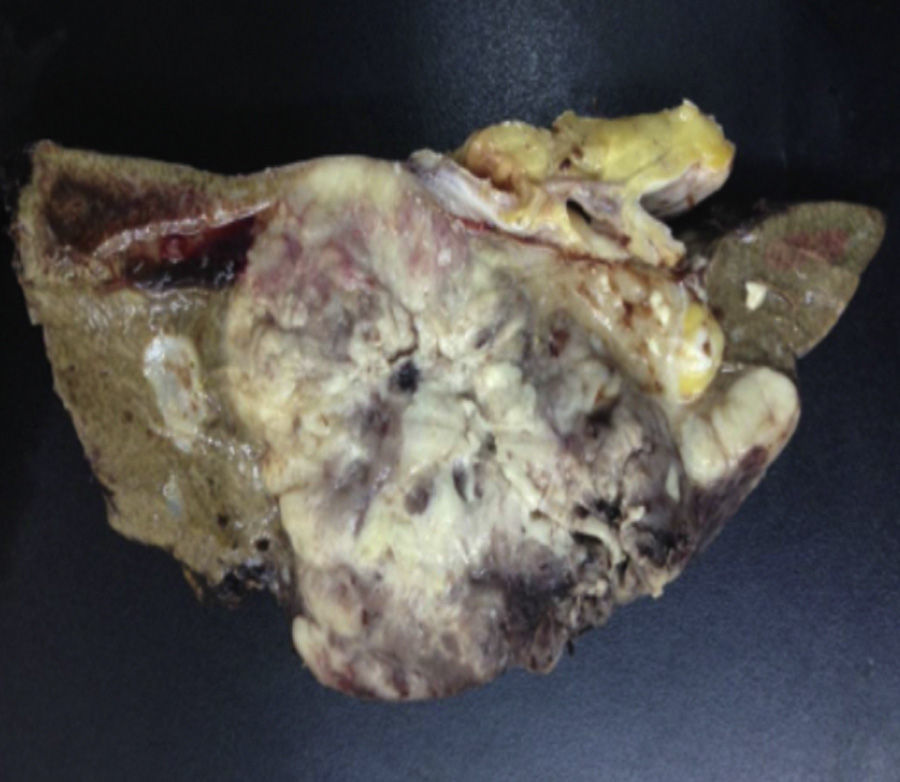

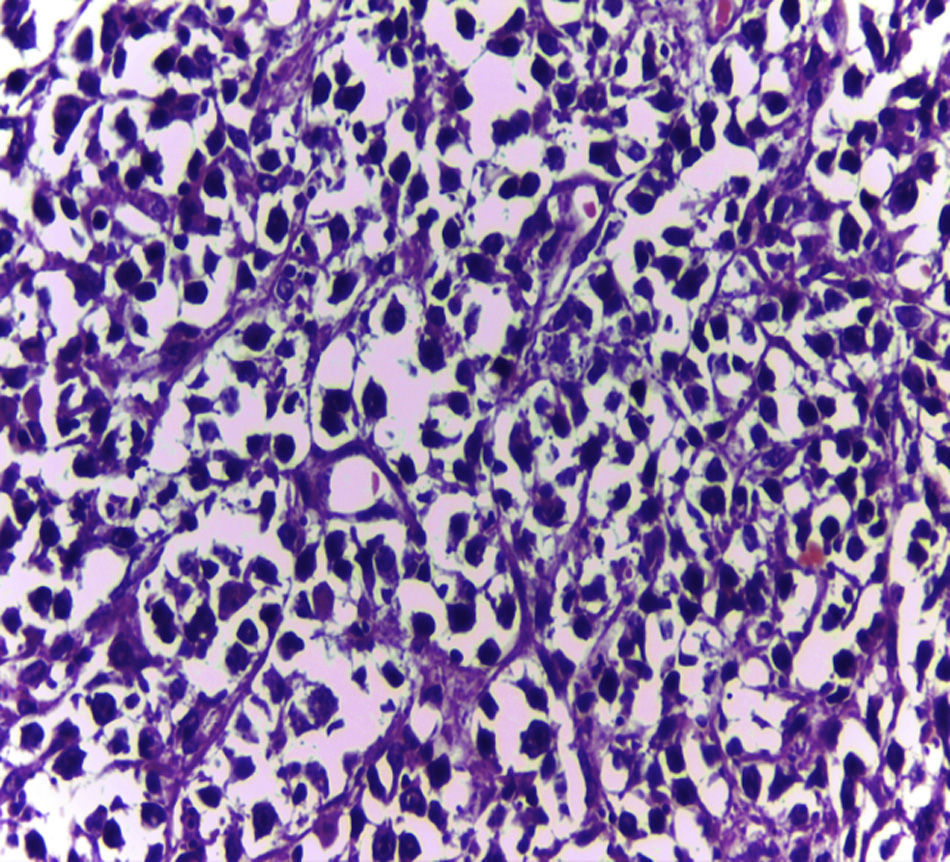

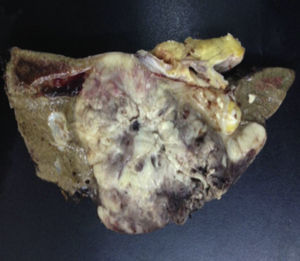

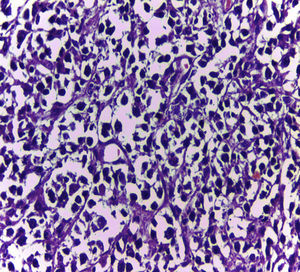

Biopsy confirmed the presence of a mass with a neoplastic appearance, infiltrative, with necrosis and bleeding in the central area (Fig. 3). Haematoxylin–eosin staining showed the presence of a diffuse neoplasm (Figs. 4 and 5), with lymphocytes staining negative for keratin and positive for leucocyte common antigen, CD20 and Bcl-2, and high Ki-67. All these findings are consistent with a diagnosis of high-grade large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. After evaluation by the haematology team, the study was complemented with HIV, HBV, HCV and cytomegalovirus (CMV) serology, which were negative. Bone marrow biopsy reported findings consistent with myelodysplastic changes associated with megaloblasts, with no lymphomatous infiltration.

The dissemination study with chest-abdomen and pelvic computed tomography (CT) showed no findings suggestive of supra- or infradiaphragmatic involvement.

The patient underwent 2 cycles of chemotherapy with R-CHOP (rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone), with a regular clinical response. She presented multiple infectious complications, eventually dying as a result of these.

DiscussionEnglish-language literature describes an incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma of 12.2 cases per 100000 population, of which only 30% present an extranodal primary site, and of these, only 0.4% manifest as PHL. B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma is most commonly associated with this entity, in approximately 60% of PHLs, compared to T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma with only 30%.4

The pathogenesis of PHL is unknown, but chronic antigen stimulation appears to play a role in the initial development of this entity. Some risk factors are known, including hepatotropic viruses such as HCV and HBV, as well as HIV and EBV.4 PHL has been associated with solid organ transplant recipients, presenting in as many as 4% of cases.4 None of these conditions were present in our patient.

In 2011, Fwu et al.6 studied a cohort of Taiwanese women, in which they found PHL rates of 3.18 cases per 100000 pregnant women with HBV surface antigen (+) compared to 1.23 cases per 100000 with HBV surface antigen (−) in a 7-year follow-up. A meta-analysis by Hartridge-Lambert et al.5 showed that HCV (+) patients with asymptomatic PHL can respond to treatment with pegylated interferon combined with ribavirin, without having to resort to surgery.

PHL usually presents in the fifth decade of life, and is more common in men. There are generally few symptoms, although approximately 70% present abdominal pain and only 10% B-symptoms. The most noticeable finding on physical examination is hepatomegaly, which is present in 50% of cases. There are some case reports in the literature of fulminant liver failure secondary to PHL, which fortunately occurs in less than 1% of cases, especially in patients with diffuse involvement.3

Laboratory tests may show multiple abnormal findings, the most frequent being the presence of an abnormal liver profile with a cholestatic pattern–although it may also be hepatic–as well as increased LDH and β2-microglobulin. Complementary imaging tests are fundamental to guide the study. Ultrasound enables visualisation of a hypo- or isointense liver nodule, but its usefulness is more limited when involvement is diffuse. Three-phase CT scan shows heterogeneous hypodense lesions with ring enhancement. The finding of calcifications and necrosis is less common.7 MRI shows hypo- or isointense lesions in T1-weighted images, with reinforcement in T2-weighted images, as presented in our case. A recent publication by Gallamini and Borra8 described the usefulness of positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) in staging, as it is more accurate in detecting nodal and extranodal involvement and provides useful information for treatment. This technology, however, was not available in our case.

Despite the foregoing, laboratory tests on our patient did not show the more notable abnormalities, and only the MRI aroused suspicion of her diagnosis.

Diagnosis was made using Lei criteria, which consider a variety of symptoms: liver involvement, absence of palpable lymphadenopathies visible on imaging tests, with no haematological involvement in the blood smear and exclusion of splenic, lymph node and bone marrow involvement.2 Nonetheless, there is a lack of consensus on the use of these criteria in the current literature. Histology is the cornerstone of PHL diagnosis and typing, so biopsy of these lesions is essential.9

Treatment for this type of tumour is controversial. Nevertheless, the literature supports the use of known regimens for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with R-CHOP, which gives higher annual survival.9,10 It is prudent–more so with the new therapies–to use antiviral therapy in those patients with concomitant HCV infection, as this may aid resolution in cases of indolent lymphoma. It is also vitally important to bear in mind the HBV serological status, due to the risk of rituximab-induced reactivation. Surgery is also described as a possible treatment, but with less promising results and higher rates of recurrence.

Survival rates can be better in PHL than in hepatocellular carcinoma if it is identified and treated correctly, with an average 5-year survival of 83.1%.2,4

In summary, PHL, despite being a rare entity, should be included in the differential diagnoses of focal hepatic lesions. Although imaging tests, such as MRI, are of great diagnostic utility, the histological study is fundamental. Management should be considered by a multidisciplinary team that includes haematologists, hepatologists and surgeons, in order to optimise the different treatment options and improve survival of this rare disease.

Please cite this article as: Mezzano G, Rojas R, Morales C, Gazitúa R, Díaz JC, Brahm J. Linfoma primario hepático: infrecuente tumor hepático primario. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:674–676.