The diagnostic and therapeutic strategy in severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) varies depending on the patient’s clinical situation. Actual clinical practice guidelines propose different management strategies. We aim to know the attitude of the gastroenterologists from different hospitalary centers in the management of this entity.

MethodsDescriptive and observational study using an on-line questionnaire, addressed to gastroenterologists in Spain and Latin America, in December 2021.

ResultsWe included 281 anonymous questionnaires of gastroenterologists from Spain and Latin America. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of severe LGIB was heterogeneous among the participants. Regarding to the first diagnostic modalities they showed variability between performing computed tomography angiography (CTA) (44.5%), gastroscopy (33.1%), colonoscopy (20.6%) and arteriography (1.1%). The therapeutic attitude after a positive CTA mostly varied between performing arteriography (38.1%) and colonoscopy (44.1%). If negative CTA, in the majority of cases a gastroscopy was performed. If the patient needed intensive critical unit (ICU) care and to undergo colonoscopy, most participants performed an urgent colonoscopy (<24 h) (31% always, 43.4% in most cases); while if the patient did not require ICU admission this percentage was lower (10% always, 33.8% in most cases). The 40.9% of the participants admitted having doubts about the management of this patients and the 98.2% considered the need for a creation of an action protocol.

ConclusionsThere is a high interhospitalary variability on the management of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding among gastroenterologyits. It is necessary to unify the diagnostic and therapeutic management of this patology.

La estrategia diagnóstico-terapéutica en la hemorragia digestiva baja (HDB) grave varía según la situación clínica del paciente. Las guías de práctica clínica actuales proponen diferentes estrategias de manejo.

ObjetivoConocer la toma de decisiones de los gastroenterólogos de distintos centros hospitalarios en el manejo de esta patología.

MétodosEstudio observacional descriptivo mediante una encuesta on-line, dirigida a facultativos de Aparato Digestivo de España y Latinoamérica, en diciembre de 2021.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 281 encuestas anónimas de facultativos de España y Latinoamérica. El manejo diagnóstico-terapéutico de la HDB grave fue heterogéneo entre los encuestados. Con respecto a los estudios iniciales mostraron variabilidad entre la solicitud de angiografía por tomografía computarizada (angioTC) (44,5%), gastroscopia (33,1%), colonoscopia (20,6%) y arteriografía (1,1%). La decisión terapéutica tras angioTC positiva variaba mayoritariamente entre la solicitud de arteriografía (38,1%) y colonoscopia (44,1%). Si la angioTC era negativa se realizaba gastroscopia en la mayoría de los casos. Si el paciente ingresaba en una Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos y precisaba colonoscopia, la mayor parte de los encuestados la realizaban urgente (<24 horas) (31% siempre, 43,4% en la mayoría de los casos); mientras que, si no requerían ingreso en intensivos este porcentaje se reducía (10% siempre, 33,8% en la mayoría de los casos). Reconocían tener dudas en el manejo de estos pacientes el 40,9% de los encuestados y consideraban necesario la creación de un protocolo de actuación el 98,2% de los participantes.

ConclusionesExiste una gran variabilidad interhospitalaria en el manejo de la HDB grave entre los gastroenterólogos. Es necesario unificar la actuación diagnóstico-terapéutica en esta patología.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIH) has traditionally been defined as bleeding distal to the angle of Treitz.1 It is a common and potentially serious condition in our environment, representing 30%–40% of all cases of gastrointestinal bleeding, causing 33–115 hospitalizations/100,000 admissions/year.1,2 It has a low mortality (1.2%–7.7%) and subsides spontaneously in 80%–90% of cases.1 Among the most common causes of LGIB are colonic diverticulosis, anorectal disease, ischemic colitis, angiodysplasia, inflammatory bowel disease, polyps and cancer.1,2

The diagnostic and therapeutic strategy in these patients varies according to the severity of the bleeding.1–6 Various studies have described risk factors associated with poor clinical course in LGIB, including the presence of hemodynamic instability (tachycardia, hypotension, syncope), continuous bleeding, associated comorbidities, age >60 years, elevated creatinine, and anemia.1

Guardiola et al.7 define severe LGIB as persistent rectal bleeding (during the first hours of admission) associated with any of the following characteristics: systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg and heart rate >100 bpm, syncope not explained by another cause, hemoglobin <9 g/dl in the absence of previous chronic anemia or a drop in Hb >2 g/dl. In this document, these criteria have been used to define patients with severe LGIB.

In the case of severe LGIB with hemodynamic instability, an initial upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is recommended, after initial stabilization, since up to 10%–20% of these patients actually present upper gastrointestinal bleeding.1,5 If it is not possible to perform an endoscopy, abdominal computed tomography angiography (CTA) is the examination of choice in these patients.2,8,9

In patients without hemodynamic compromise, colonoscopy is the diagnostic modality of choice due to the therapeutic possibilities it offers.1,4 However, the results of this exploration are variable, and the optimal moment for performing it is currently controversial.

Thus, in the latest guidelines published by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) it is stated that, for the moment, there is no quality evidence to show that early colonoscopy, performed in the first 24 h after presentation, influences patient outcomes.2,10,11 However, at the moment, it is not clear if selected patients with acute LGIB could benefit from an early colonoscopy.2

Nevertheless, the American LGIB guidelines recommend that patients with high-risk clinical characteristics and signs or symptoms of continuous bleeding undergo early colonoscopy, under hemodynamically stable conditions and after bowel preparation.12 Likewise, the Japanese guidelines for the management of acute LGIB also recommend performing a colonoscopy in the first 24 h to identify the source of bleeding, as well as performing a therapeutic intervention.13 It should be noted that these guidelines predate the publication of two recent randomized studies,10,11 which show that early colonoscopy does not reduce the risk of rebleeding, mortality, or the need for transfusion; endoscopy being a procedure with a more diagnostic than therapeutic benefit.

Given the discrepancy of recommendations in the different current clinical practice guidelines, the objective of this study was to find out, through an international online survey, aimed at gastroenterology specialists and residents, about the decision-making of gastroenterologists in the management of patients with severe LGIB.

Patients and methodsType of study and sampleA descriptive observational study was carried out through an online survey disseminated through different social media networks, aimed at gastroenterology specialists and residents in Spain and Latin America during the month of December 2021. Participants completed the survey voluntarily and anonymously.

Data collectionThe survey was created on the Google Form® platform and was disseminated via different social media (WhatsApp®, Twitter®) and emails sent to gastroenterology working groups, keeping it active from 15 to 31 December 2021.

The survey was prepared by gastroenterology specialists at the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo (CHUVI) [Vigo University Hospital Complex]. The form consisted of 24 questions, five of them related to epidemiological aspects (age, sex, country, type of hospital, and professional category), five related to infrastructures available at the health center (endoscopy, CTA, interventional radiology, surgery, intensive care unit [ICU]), 10 related to the additional tests requested for patients with severe LGIB (usually performed a first examination, attitude to follow after negative/positive CTA, time of colonoscopy, preparation before urgent colonoscopy, and type of solution administered) and four related to the protocols available for the management of these patients (existence and need for action protocols, clinical practice guidelines used, uncertainty in the management of this condition). The complete questionnaire is included in Appendix B Annex 1 of this document.

Statistical analysisData analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS® v.21.0. A descriptive analysis of the qualitative variables expressed in number and percentage was used.

ResultsA total of 281 anonymous surveys of gastroenterologists were included in the study: 141 were male (50.2%) and 140 were female (49.8%). Of these, 79 (28.1%) were between 20 and 30 years old, 104 were between 31 and 40 years (37%), 55 were between 41 and 50 years (19.6%), 27 were between 51 and 60 years (9.6%), 14 were over 60 years of age (5%), and the age of two of the participants (0.7%) was unknown. Two hundred twenty-three of the participants were attending physicians (79.4%) and 58 were residents (20.6%), four of them first-year (1.4%), 12 s-year (4.3%), 15 third-year (5.3%) and 27 fourth-year (9.6%).

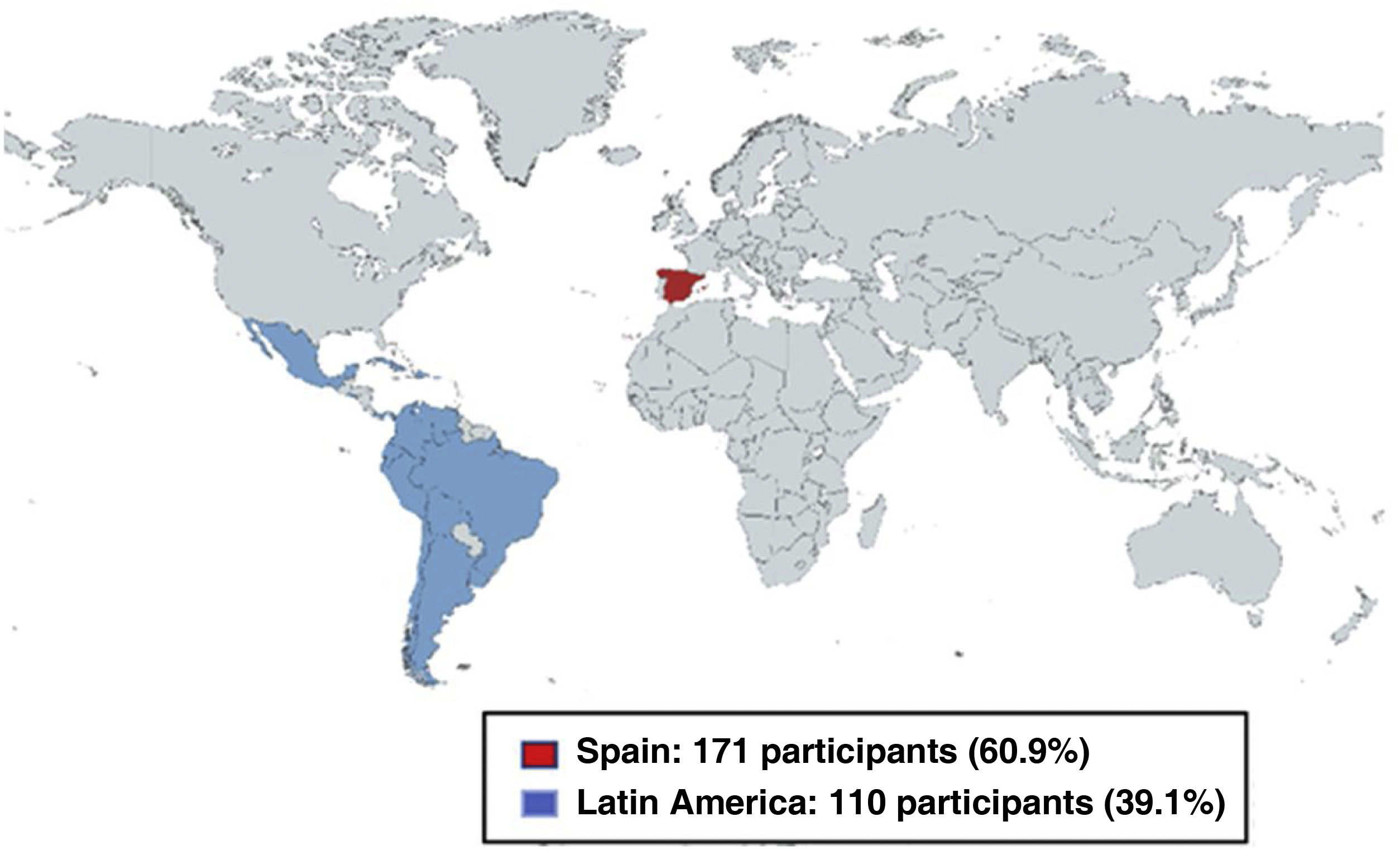

Of the physicians who participated, 171 (60.9%) were from hospitals in Spain and 110 (39.1%) were from 15 Latin American countries: Mexico, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Panama, Peru, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Uruguay and Venezuela (Fig. 1). Of those surveyed, 197 worked in a tertiary hospital (70.1%), 65 in a secondary hospital (23.1%) and 19 in a primary hospital (6.8%). In all, 231 of the participants (82.3%) had a 24-h endoscopist at their center, 162 of them off-site on-call (57.7%) and 69 on-site on-call (24.6%).

Of the 281 participants, 236 had CT angiography at their center (84%), 189 had interventional radiology (67.3%), 274 had surgery (97.5%), and 273 had an ICU (97.2%).

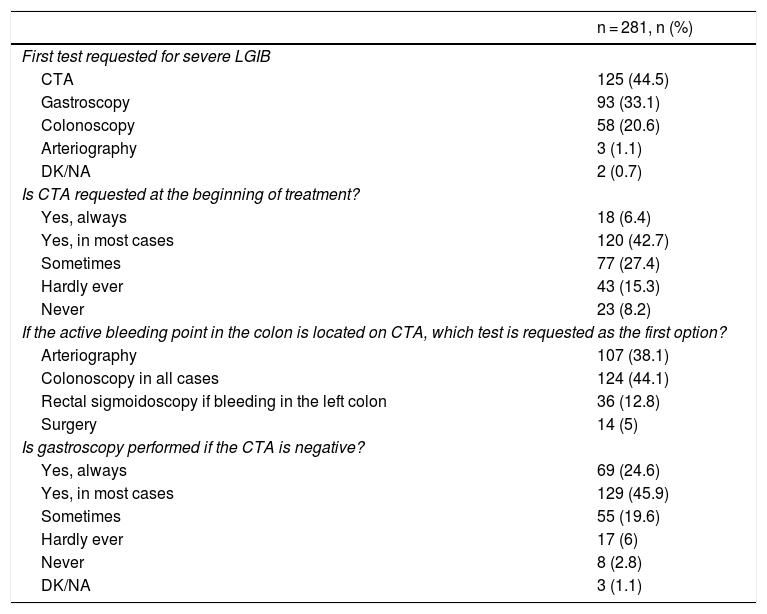

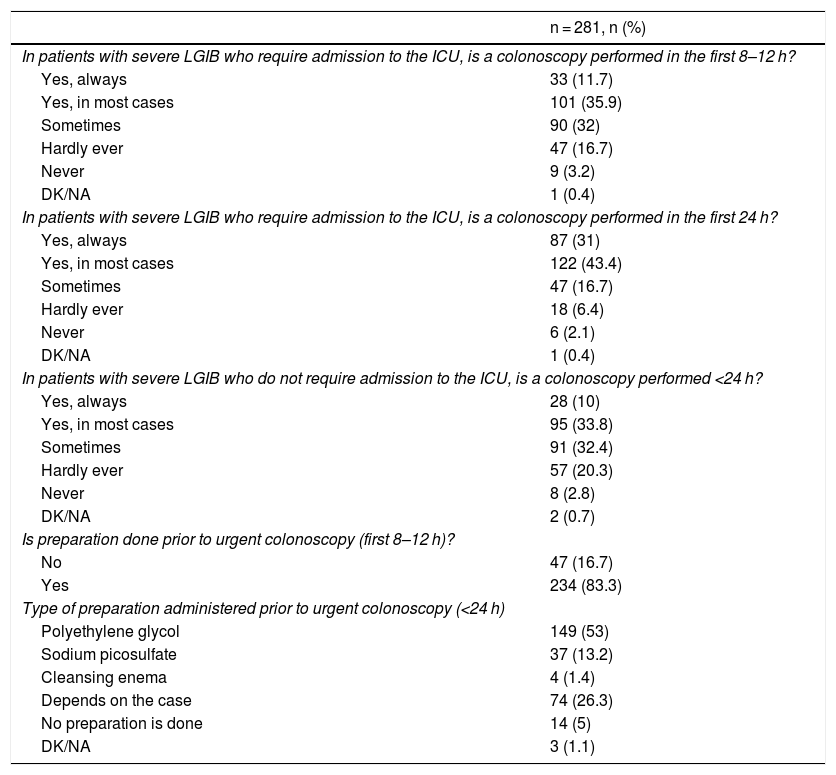

One hundred twenty-five of the respondents (44.5%) requested CTA as the first complementary test in patients with severe LGIB, 93 of them (33.1%) a gastroscopy and 58 (20.6%) a colonoscopy. Most of the respondents (83.3%) carried out preparation prior to urgent colonoscopy and more than half of them (53%) used polyethylene glycol as a preparation solution. The data referring to the questions about the attitude of the gastroenterologist regarding the complementary tests requested for patients with severe LGIB are shown in Table 1. Meanwhile, Table 2 shows the timing and type of preparation prior to colonoscopy if performed.

Results of the survey on the complementary tests requested in patients with severe LGIB.

| n = 281, n (%) | |

|---|---|

| First test requested for severe LGIB | |

| CTA | 125 (44.5) |

| Gastroscopy | 93 (33.1) |

| Colonoscopy | 58 (20.6) |

| Arteriography | 3 (1.1) |

| DK/NA | 2 (0.7) |

| Is CTA requested at the beginning of treatment? | |

| Yes, always | 18 (6.4) |

| Yes, in most cases | 120 (42.7) |

| Sometimes | 77 (27.4) |

| Hardly ever | 43 (15.3) |

| Never | 23 (8.2) |

| If the active bleeding point in the colon is located on CTA, which test is requested as the first option? | |

| Arteriography | 107 (38.1) |

| Colonoscopy in all cases | 124 (44.1) |

| Rectal sigmoidoscopy if bleeding in the left colon | 36 (12.8) |

| Surgery | 14 (5) |

| Is gastroscopy performed if the CTA is negative? | |

| Yes, always | 69 (24.6) |

| Yes, in most cases | 129 (45.9) |

| Sometimes | 55 (19.6) |

| Hardly ever | 17 (6) |

| Never | 8 (2.8) |

| DK/NA | 3 (1.1) |

CTA: abdominal computed tomography angiography; LGIB: lower gastrointestinal bleeding; DK/NA: don't know, no answer.

Results of the survey about the timing and preparation prior to colonoscopy.

| n = 281, n (%) | |

|---|---|

| In patients with severe LGIB who require admission to the ICU, is a colonoscopy performed in the first 8–12 h? | |

| Yes, always | 33 (11.7) |

| Yes, in most cases | 101 (35.9) |

| Sometimes | 90 (32) |

| Hardly ever | 47 (16.7) |

| Never | 9 (3.2) |

| DK/NA | 1 (0.4) |

| In patients with severe LGIB who require admission to the ICU, is a colonoscopy performed in the first 24 h? | |

| Yes, always | 87 (31) |

| Yes, in most cases | 122 (43.4) |

| Sometimes | 47 (16.7) |

| Hardly ever | 18 (6.4) |

| Never | 6 (2.1) |

| DK/NA | 1 (0.4) |

| In patients with severe LGIB who do not require admission to the ICU, is a colonoscopy performed <24 h? | |

| Yes, always | 28 (10) |

| Yes, in most cases | 95 (33.8) |

| Sometimes | 91 (32.4) |

| Hardly ever | 57 (20.3) |

| Never | 8 (2.8) |

| DK/NA | 2 (0.7) |

| Is preparation done prior to urgent colonoscopy (first 8–12 h)? | |

| No | 47 (16.7) |

| Yes | 234 (83.3) |

| Type of preparation administered prior to urgent colonoscopy (<24 h) | |

| Polyethylene glycol | 149 (53) |

| Sodium picosulfate | 37 (13.2) |

| Cleansing enema | 4 (1.4) |

| Depends on the case | 74 (26.3) |

| No preparation is done | 14 (5) |

| DK/NA | 3 (1.1) |

LGIB: lower gastrointestinal bleeding; DK/NA: don't know, no answer; ICU: intensive care unit (including resuscitation unit).

Of the 281 respondents, 276 considered it necessary to create an action protocol (98.2%) and 170 of them (60.5%) answered that they did not have it at their hospital. One hundred fifty-five of the participants (55.2%) reported following the ESGE clinical practice guidelines, 27 participants followed the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines and 10 (3.5%) followed the American Gastroenterology guidelines. Forty-eight (17.1%) answered that they did not follow any clinical practice guidelines for the management of these patients, and six participants (2.1%) had their own hospital protocol.

One hundred fifteen of those surveyed (40.9%) admitted having doubts about the management of patients with severe LGIB.

DiscussionLGIB is a common and potentially serious condition in our environment. The results obtained in our study show how nationally and internationally there is great variability in the management of this condition.

Most clinical practice guidelines recommend colonoscopy as the test of choice in patients with LGIB without hemodynamic compromise, given the therapeutic options it offers.1,5 However, in patients with hemodynamic instability, CT angiography or upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is initially recommended if this does not identify any source of bleeding or if the patient stabilizes after initial resuscitation.2 According to the participants in the survey, there is great variability in terms of the first complementary test requested in these patients, since a non-negligible percentage would initially request a colonoscopy in these cases (20.6%), while another relevant percentage of participants would choose a gastroscopy as the first examination (33.1%). These results demonstrate the great diversity that there is among different gastroenterologists when it comes to managing LGIB. It should be noted that there is available evidence showing that to detect active bleeding on CTA, a bleeding flow of 0.5−1 mL/min8 is required, which clinically translates into the presence of hemodynamic instability or high transfusion requirement. The definition of severe LGIB used in this study included the presence of hemodynamic instability, but also anemia below <9 g/dL in the absence of chronic anemia or a drop in hemoglobin >2 g/dl,7 so this fact could have generated controversy and doubts about the initial decision to perform gastroscopy or CT angiography.

Regarding the optimal time to perform colonoscopy, there is controversy between the recommendations offered by the different clinical practice guidelines. While some guidelines recommend early colonoscopy (<24 h) in patients with high-risk clinical characteristics, others recommend delayed colonoscopy during the hospital stay given the lack of evidence of the benefits of early endoscopy. Again, our results show great variability among the participants' responses in this regard, indicating the need to protocolize and standardize our care in routine clinical practice when managing this condition, about which the majority of those surveyed agreed. In fact, only a minority of the participants indicated that they had an intrahospital LGIB protocol.

Regarding preparation prior to urgent colonoscopy, current guidelines for the management of LGIB do not recommend performing colonoscopy without prior preparation and suggest the use of a solution based on polyethylene glycol.2 In this regard, there is consensus among those surveyed, since the majority comply with the recommendations and carry out preparation prior to colonoscopy. Furthermore, half of them use the polyethylene glycol solution suggested by the most recent guidelines.

The limitations of the study include the small sample size, which may limit the extrapolation of its results. In addition, it is worth noting the limitations and biases of surveys in terms of the veracity of participants' answers, even when anonymous, since the answers could correspond more to ideal clinical practice than to actual practice. Likewise, the use of closed questions could also limit the information obtained. In addition, the fact that all the participants are gastroenterologists could be considered a bias, since LGIB is often managed by other specialists (internists, emergency physicians…), who would not be represented in this study.

The main strength of the study is that it allowed us to find out aspects of routine clinical practice quickly, easily and at no cost, opening up the possibility of developing other studies of interest and with greater impact in the future. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first international and multicenter study that evaluates our decision-making in patients with severe LGIB.

ConclusionsThere is great interhospital variability in managing severe LGIB, which is reflected in the great heterogeneity that exists in decision-making by gastroenterologists when dealing with this condition.

For this reason, we consider it necessary to prepare care protocols adapted to each hospital according to the characteristics and infrastructure of the center, based on existing clinical practice guidelines.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.